Mexico City is a flourishing metropolis with a plethora of historic and modernist architectural sites. Here are a few attractions scattered around the city.

Read More9 Beautiful Houses of Worship Around the World

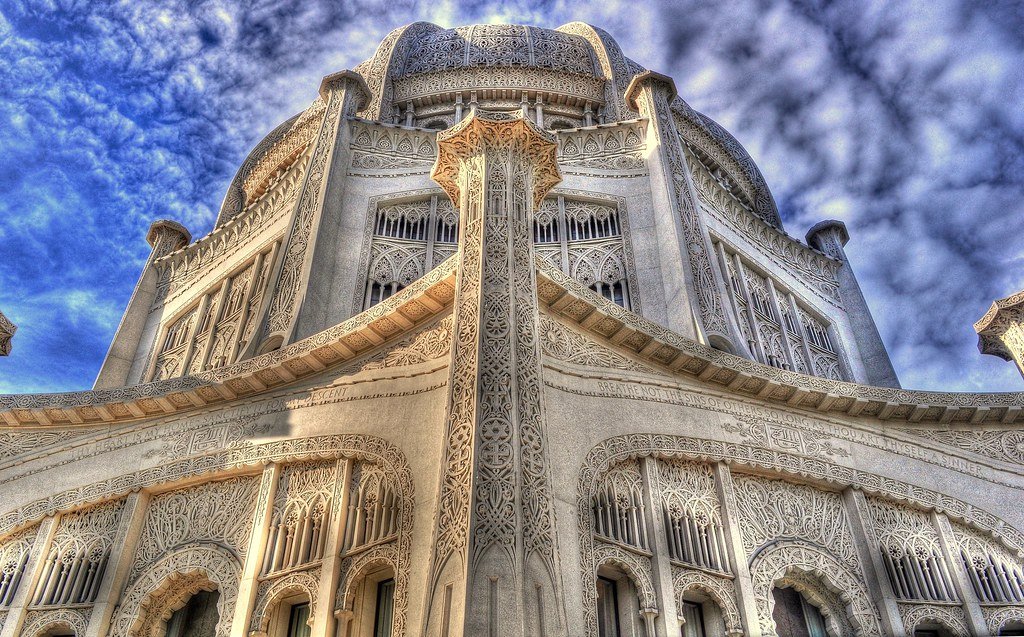

Different religions have different ways of showcasing their houses of faith.

For many centuries across the globe, people have built houses of faith to honor the higher power(s) they worship. Below is a list of different architectural representations of these sacred spaces.

1. Borgund Stave Church

Borgund, Norway

The portrayal of dragon heads on the roof of the Borgund Stave Church in Norway was built to ward off spirits in 1180. The church was dedicated to Apostle Andrew and has been incredibly preserved. The medieval church received certification in 2010 for being an environmental lighthouse. The church is set to reopen to visitors on April 15.

2. Golden Temple

Amritsar, India

Named the holiest temple in the Sikh faith, the Golden Temple’s upper floors are covered in 750 kilos of pure gold. It was built by Guru Arjan in 1604 and is located in the Northwest of India, near the border of Pakistan. It is said that the waters surrounding the temple in the river Ganga cleanse one’s bad karma when taking a dip. It is visited by 100,000 worshippers daily.

3. Hallgrímskirkja

Reykjavik, Iceland

This Lutheran Icelandic church was built by architect Guðjón Samúelsson and, at 240 feet, stands as the tallest building in the capital and the second tallest in all of Iceland. The design is influenced by the country's volcanoes and the natural surroundings that inhabit the nation. Visible from almost any point in the city, the church is known as one of Iceland’s landmarks and largest church.

4. Kizhi Pogost

Kizhi Island, Russia

Kizhi Pogost. Alexxx Malev. CC BY-NC 2.0

Set on Kizhi Island in Russia’s Lake Onega, Kizhi Pogost is a UNESCO World Heritage site consisting of two wooden churches and a bell tower built in 1714. What makes this an incredible architectural structure is that it was made completely of wood, with no metal or nails involved. Today, the churches are an open air museum.

5. Wat Rong Khun

Chiang Rai Province, Thailand

Designed by Thai visual artist Chalermchai Kositpipat, Wat Rong Khun (also known as The White Temple) was created to honor Buddha’s purity. There are many intricate details in the space, including carvings of monkeys, people and hands among other things. Today, Kositpipat has only completed three of the nine buildings he has plans for. The temple entrance cost is $1.50, Kositpipat will not accept more because he does not want large donors to influence his art. The temple is being run by a team of volunteers.

6. Las Lajas Sanctuary

Ipiales, Colombia

Las Lajas Sanctuary. BORIS Gt. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Located less than seven miles from the Ecuadorian border, Las Lajas Sanctuary sits over the Guaitara River. The Roman Catholic basilica has three iconic features. First, the bridge has statues of angels playing instruments on each side. The second is the stained glass by Italian artist Walter Wolf. Lastly, there is an image of the Virgin Mary painted on the back stone wall. The neo-Gothic basilica is surrounded by lush vegetation and was named the most beautiful church in 2015 by The Telegraph.

7. Great Mosque of Djenné

Djenné, Mali

Great Mosque of Djenné. Mission de l'ONU au Mali. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Globally known as an example of Sudano-Sahelian architecture and one of Africa’s most famous structures, the Great Mosque of Djenné was built in 1907 from mud and brick, which needs regular replastering to keep its form. Today, the Great Mosque is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a sacred destination for Muslims.

8. Jubilee Synagogue

Prague, Czech Republic

Jubilee Synagogue. BORIS G. CC BY 2.0

The colorful and intricate Jewish Jubilee Synagogue, also known as the Jerusalem Street Synagogue, was built in 1906 by architect Wilhelm Stiassny to commemorate the Emperor Franz Joseph I’s ascension to the throne. A preserved organ by composer Emanuel Stephen Peter is played for visitors. Today, it is open to the public and used for Orthodox prayer services.

9. Szeged Synagogue

Szeged, Hungary

New Synagogue. Emmanuel Dyan. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The second largest synagogue in Hungary, Szeged Synagogue merges Art Nouveau with Gothic, Moorish, Byzantine, Roman and Baroque interior design. The sanctuary’s seating faces a Torah ark made with wood from the banks of the Nile River. The triumphal arch of the building displays the biblical commandment, “Love your neighbor as yourself" in both Hebrew and Hungarian.

10. Temple of Heaven

Beijing, China

Temple of Heaven in Beijing. Fabio Achilli. CC BY 2.0

An imperial sacrificial altar, the Temple of Heaven in Dongcheng District, Beijing is considered the “supreme achievement of traditional Chinese architecture.” It is 273 acres and located in a large park, measuring 38 meters high and 30 meters in diameter, built on three levels of marble stones. It was completed during the Ming dynasty in 1420 and used to pray for harvest and for worship. In 1998, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Jennifer Sung

Jennifer is a Communications Studies graduate based in Los Angeles. She grew up traveling with her dad and that is where her love for travel stems from. You can find her serving the community at her church, Fearless LA or planning her next trip overseas. She hopes to be involved in international humanitarian work one day.

VIDEO: India’s "Death Hotels"

Varanasi, the most sacred of India’s seven holy cities, is home to several so-called “death hotels.” Unlike their morbid name, these hotels are actually places of peaceful worship where devout Hindus aspire to reach moksha — liberation from the infinite cycle of rebirth. Believers check in and remain until they die, a time that ranges from days to years. This video explores the ancient, often emotional, rituals of preparing for moksha from the viewpoint of hotel owners, pilgrims, cremation workers, and the family of those soon to be departing. Set on the banks of the Ganges River, it intertwines themes of religion, caste, family, and mortality into a masterpiece that shows an entirely new perspective on how to deal with death.

Muslim Victims of India’s Worst Riots Fret Over Delayed Justice

For victims of any crime, the wait for justice to be served is often a painstaking process where emotions run high. The victims of last year's Hindu riots in New Delhi now feel that any hope for justice has fizzled away.

A Muslim praying in a mosque in New Delhi. Riccardo Maria Mantero. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Almost exactly a year ago, India’s bustling capital of New Delhi broke out into the worst religious rioting seen in the country since 1984. For four bloody days, Hindu mobs ravaged the city targeting Muslims, many of whom grew up experiencing peaceful relations with their Hindu neighbors. The mobs set fire to Muslims’ homes and mosques, while others dragged Muslims into the streets where they were mercilessly beaten to death. Muslims were also wounded by crowbars and iron rods, while others were lynched. Families were burned alive as the violence ensued, often by Hindus wearing helmets to prevent police identification. One victim, Mohammad Zubair, was seen crouching on a dirt street with his hands over his head; he prayed as a group of men beat him senseless. Zubair narrowly survived after the mob left his barely conscious body for dead in a nearby gutter.

“… a letter was found from a police chief calling on officers to ease punishments toward Hindus involved.”

Although a horrific scene, religious tensions and rioting are certainly nothing new to India. Hindus make up around 80% of the country’s population, while 15% are Muslims. The two groups have been in conflict since the country’s inception, but the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has exacerbated tensions to unprecedented levels.

Now, a year has passed since the riots. Although the peak of violence has passed over, neither the widespread tension nor the fear among Muslim residents has eased. Most victims of the rioting find themselves at a dead end: police have often refused to help victims due to political ties with the currently elected Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has connections to Hindu nationalist groups. Many victims worry that the ruling party actually supported the riots against Muslims.

Local police view the situation differently. They claim that the necessary investigations were carried out, and that almost 1,750 perpetrators were punished. Evidence seems to show otherwise; a letter was found from a police chief calling on officers to ease punishments toward Hindus involved.

In addition, the complex situation has led to a web of accusations. Kapil Mishra, a leader of the BJP, believes that the riots were started by the Muslim population to incite violence against Hindus. Other Hindus claim that Muslims were behind the rioting, claiming that the goal was to tarnish India’s image on the world stage.

Unfortunately, the situation for Muslim victims appears bleak. All that can be done now is for the anguished residents to wait some more and hope for a new path forward.

Ella Nguyen

Ella is is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.

Sudanese people gathering in front of a mosque. Nina R. CC 2.0.

Sudan Separates Religion and State Following al-Bashir’s Ouster

The Northeast African nation of Sudan has made the decision to separate religion from the state, dissolving 30 years of governance by Islamic law. The country, which has been attempting to rebuild itself after long periods of colonial rule and political strife, came to this decision in an attempt to quell current tensions between religious and military groups.

Sudan was formerly under colonial rule by the United Kingdom, though the British did not make their presence in Sudan a physical one. They maintained control by partnering with Egypt through a dual colonial government known as the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1899–1956). This agreement separated the Muslim-dominated north from the majority-Christian south. As colonial presence grew stronger in the region, so did division along ethnic, socioeconomic, religious and linguistic lines.

Sudan was able to gain independence in 1956, but the country is still overwhelmed with tensions as its citizens and government continue to reconcile with issues caused by colonization. They eventually led to the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005) between the central government in Khartoum and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, causing an eventual 2 million deaths and the creation of an independent South Sudan. This conflict was amplified when Omar al-Bashir took office by way of a military coup in 1989 in the middle of this 22-year-long civil war. He ruled for 30 years and did so through the suppression of political opponents as well as violence against the Sudanese people. During his presidency, multiple arrest warrants were issued to al-Bashir by the International Criminal Court on charges including war crimes and crimes against humanity, such as his attacks on citizens in Darfur.

Map of Sudan. Muhammad Daffa Rambe. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Al-Bashir continued to hold his power until April 2019 when, after months of unrest, the Sudanese military toppled him. On Sept. 3, 2020, Sudan issued its declaration to sever ties between mosque and state, saying that, “For Sudan to become a democratic country where the rights of all citizens are enshrined, the constitution should be based on the principle of ‘separation of religion and state,’ in the absence of which the right to self-determination must be respected.”

Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. Ola A .Alsheikh. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and Abdelaziz al-Hilu, leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North rebel group, signed this document together. Additionally, the document emphasizes its effort toward unity with the statement, “Sudan is a multiracial, multiethnic, multireligious and multicultural society. Full recognition and accommodation of these diversities must be affirmed.” More than simply separating church and state, the declaration gives the country momentum in its push toward unification.

Renee Richardson

Renee is currently an English student at The University of Georgia. She lives in Ellijay, Georgia, a small mountain town in the middle of Appalachia. A passionate writer, she is inspired often by her hikes along the Appalachian trail and her efforts to fight for equality across all spectrums. She hopes to further her passion as a writer into a flourishing career that positively impacts others.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and U.S. President Donald Trump. IsraelMFA. CC BY-NC 2.0.

A Surge in Condemnations Follows Israel’s Annexation Plans for the West Bank

The prime minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, is planning to annex parts of the West Bank on July 1 to extend Israeli sovereignty to new areas. This is a controversial and illegal move according to U.N. experts and much of the international community but comes with the support of the Trump administration.

According to 47 experts appointed by the U.N. Human Rights Council, "The annexation of occupied territory is a serious violation of the Charter of the United Nations and the Geneva Conventions, and contrary to the fundamental rule affirmed many times by the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly that the acquisition of territory by war or force is inadmissible. These experts also deemed Israel’s annexation plan “a vision of 21st century apartheid.”"

Palestinians, Palestinian leaders, and leaders of the Arab world have largely condemned this plan. In the first attempt of its kind, the United Arab Emirates’ ambassador to the United States, Yousef Al Otaiba, wrote in an Israeli newspaper to appeal “directly to Israelis in Hebrew to deter Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from following through on his promise to annex occupied territory as early as next month,” says The New York Times. The article was a refutation of Netanyahu’s assertion that Arab countries gain too much from Israel to continue supporting Palestinians. In addition to those concerns, many former Israeli defense officials argue that the annexation plan could increase violence within the West Bank, where Palestinians are facing an increase in unemployment. “Imposing Israeli sovereignty on territory the Palestinians have counted on for a future state,” Israeli experts say, “could ignite a new uprising on the West Bank. Neighboring Jordan could be destabilized.”

The news of an annexation plan has brought about new pleas from the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement (BDS), created in 2005 by Palestinians to end international support for Israel’s actions in the West Bank . In May 2020, various Palestinian civil rights groups, human rights organizations, and unions “called on governments to adopt ‘effective countermeasures, including sanctions’ to ‘stop Israel’s illegal annexation of the occupied West Bank and grave violations of human rights.’”

The BDS movement saw a huge victory on June 11 when the European Court of Human Rights shut down France’s attempt to criminalize BDS activists in a 2015 case. At the time of the arrests, the activists were said to be inciting discrimination against a group of people for their origins, race or religion. In the end “the European judges ruled that as citizens these activists had the right to express their political opinions, which are in no sense discriminatory against a race or a religion.” Netanyahu’s expeditious plan to annex is likely to bring about more condemnations from the international community and increase support for the BDS movement, but it is unclear whether these actions will actually halt his plan.

Hanna Ditinsky

is a sophomore at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is majoring in English and minoring in Economics. She was born and raised in New York City and is passionate about human rights and the future of progressivism

"Indian Flag at Sriperumbdur" by rednivaram is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Delhi Muslims Still Rebuilding Their Lives After Days of Deadly Riots

Almost three weeks after religious violence erupted in Delhi, India, thousands of Muslims are still displaced, most living in relief camps that are overwhelmed by the number of people who have lost everything.

Hindu mobs attacked neighborhoods in the northeast area of New Delhi on Sunday, February 23, 2020. At least 53 people have been killed and more than 200 injured in what is being called the worst violence New Delhi has seen in decades. The three days of violent attacks included the torching and looting of schools, homes, mosques, and businesses. “Mobs of people armed with iron rods, sticks, Molotov cocktails and homemade guns ransacked several neighborhoods, killing people, setting houses, shops and cars on fire”, according to CBS News. The New York Times reported, “Gangs of Hindus and Muslims fought each other with swords and bats, shops burst into flames, chunks of bricks sailed through the air, and mobs rained blows on cornered men.” These attacks came after months of mainly peaceful protests by people of all faiths over changes to citizenship laws that allowed discrimination against Muslims.

The new law, called the Citizenship Amendment Bill, uses a religious test to determine whether immigrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan can be considered for expedited Indian naturalization. All of South Asia’s major religions were included—except Islam. According to CBS News, those who oppose the law say, “it makes it easier for persecuted minorities from the three neighboring nations of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh to get Indian citizenship - unless they are Muslim.” Kapil Mishra, a local Hindu politician of the Hindu nationalist party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, told India’s police that they needed to break up the protests against the law, or he and others would take it into their own hands.

Doctors at the Mustafabad Idgah camp (one of the largest camps) are reporting that many of the survivors are showing early signs of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression. The makeshift relief camps are overcrowded and undersupplied, and are lacking in some sanitation amenities. Due to the lack of hygiene amenities, many are suffering from urinary tract infections and skin rashes. The lack of basic hygiene amenities is even more dangerous and deadly amid the global coronavirus pandemic.

Muslims found help from another religious minority in India: Sikhs. A Sikh man, Mohinder Singh, and his son, Inderjit, helped sixty people get to safety by tying turbans around their heads so they would not be recognized as being Muslim. Sikhs themselves experienced large-scale religious violence in October 1984 when 3,000 Sikhs were killed in Delhi after the assassination of then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Khalsa Aid, a non-profit organization founded upon Sikh principles, was one of the first groups to provide aid to the victims. Members of the organization helped by assisting in repairing looted and damaged shops. They also opened a “langar”, a Sikh term for a community kitchen that serves free meals to all visitors—regardless of religion, caste, gender, or ethnicity.

Asiya Haouchine

is an Algerian-American writer who graduated from the University of Connecticut in May 2016, earning a BA in journalism and English. She was an editorial intern and contributing writer for Warscapes magazine and the online/blog editor for Long River Review. She is currently studying for her Master's in Library and Information Science.

@AsiyaHaou

Truckistan

Pakistani truck owners have taken moving art to a new level with their mobile murals on their vehicles. Check out this vibrant video about Pakistan truck art and culture.

Read MoreFlavour, a popular Nigerian musician, can wear his dreadlocks in peace because they are seen as a temporary fashion statement. Elizabeth Farida/Wikimedia Commons

In Nigeria, Dreadlocks Are Entangled with Beliefs About Danger

A grown man wearing his hair in dreadlocks is bound to attract attention in Nigeria. And it’s not always positive attention. Many Nigerians, regardless of their education and status, view dreadlocked men as dangerous. The hairstyle sometimes even gets a violent reaction.

This bias is deeply rooted in traditional religious beliefs and myths, especially those of the Yoruba and Igbo people.

My book on the symbolism of dreadlocks in Yorubaland tries to explain what knotted hair means to Yoruba people, and where these ideas come from. Numbering around 40 million, Yoruba people predominantly occupy southwestern Nigeria. In West Africa, they are found in Benin Republic, Ghana, Togo, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. In the diaspora, they are significantly present in the US, Brazil, Cuba, Haiti and the Caribbean.

An affront to society’s orderliness

A popular phrase used by Yoruba people to describe dreadlocks is “a crazy person’s hair”. The language also has an idiom that shows how people feel about madness. A person will ask, “kini ogun were?” (what is the cure for madness?) and get the response, “egba ni ogun were” (whip is the cure for madness).

Mentally disturbed people often wear dreadlocks due to neglect. Because they are unpredictable, they are avoided as they roam the streets, and sometimes beaten. Their knotted hair show disharmony with the community; being unkempt and unruly, they are viewed as an affront to societal norm of orderliness.

Adult men with dreadlocks are viewed similarly. They are perceived as volatile and dangerous. Their untamed hair connotes wildness. Therefore, they are associated with the wilderness; uncultivated and unruly. In traditional Yoruba and Igbo worldview, unkempt hair is akin to the forest – mysterious, dark, and to be avoided.

There are exceptions: musicians and athletes who wear these hairstyles are “tolerated” as they are presumed to be assuming a persona that matches their brand. Essentially, theirs is a temporary fashion statement. And because they are famous and successful, they are protected from attacks on the streets.

Dark and frightening by tradition

The Yoruba thought system has it that some children are raised in the forest by gnomes and other mysterious beings. They come back into the community with supernatural powers, strange mannerisms, and sometimes knotted hair. Since they traverse the physical and spiritual worlds, it is believed that they can discern the destiny of others and can negatively influence them.

These knotted-haired people are avoided, more so when their dreadlocks are greying because “normal” adult Igbo and Yoruba males shave their heads completely, or they cut their hair very short. Deviating hairstyles are viewed suspiciously.

Unlike adult males, children born with knotted hair are revered and welcomed as a gift of the gods and not a product of the wild. Such children are called “dada” among the Yoruba in western Nigeria and the Hausa in the north. In south eastern Nigeria, the Igbo call them “ezenwa” or “elena”.

In Yoruba mythology, Dada is the son of Yemoja, the goddess of the sea, wealth, procreation, and increase. Dada is said to be one of the deified Yoruba kings. His younger brother is believed to be Shango, the god of thunder, who wears cornrows.

Children-dada are presumed to be spiritual beings and descendants of the gods by virtue of their dreadlocks. As such, their hair is not to be groomed and can only be touched by their mothers. They are the bringers of wealth, which is symbolised in both Yoruba and Igbo cultures by cowrie shells. They are celebrated. Feasts are held in their honour.

Their time on earth is special. It is marked by special rites that define different phases of life. In nearly all cases, their hair is shaved before puberty in order to integrate them into the community. The shaving ritual takes place at a river, where the shaved head is washed. The cut hair is then stored in a pot containing medicinal ingredients and water from the river. The concoction is believed to have healing properties and needed when they fall ill.

After the hair-shaving ceremony, the dada wears “tamed” hair in conformity with societal expectations. The child is still recognised as special and mysterious but is now integrated into society. The visible sign of their spirituality is no longer present. Any grownup, therefore, who still wears their dreadlocks is deemed to have been possessed by evil forces, or chose to do so malevolently; in either case, dangerous.

Challenges to the culture

Despite their negative associations, dreadlocks increased in Nigeria’s religious and popular cultures in the 1960s. Itinerant priests of the Celestial Church of Christ appear in white gowns and knotted hair. The famous musician and talented artist from Osogbo, Twin Seven Seven, performed on stage and television with his dreadlocks and white attire. He was the sole survivor of seven (considered a mysterious number in Yoruba tradition) sets of twins.

Yorubaland has the highest rate of twins in the world. Twins are considered spiritual beings, so they are also revered and celebrated. Being a twin, having knotted hair, and only wearing white clothes (like the gods or ghosts), further mystified Twin Seven-Seven in popular imagination and fanciful stories about him spread. For example, it was said that he was raised in the forest by spiritual beings, hence his creative imagination and hairstyle.

In the 1970s and 80s, other Nigerian musicians like Majek Fashekwere inspired by the fame of Jamaican reggae artists to begin styling their hair the same way. From the 1990s, Nigerian footballers joined in by wearing cornrows and dreadlocks.

Barring these exceptions, adults with unkempt hair are judged deviant beings who have become conduits for evil. Since it is difficult to differentiate between adults wearing dreadlocks as fashion statement from those with “evil dreadlocks”, people either flee from them or attack them out of fear and self preservation.

Augustine Agwuele is a Professor, Department of Anthropology, Texas State University

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Panama Celebrates its Black Christ, Part of Protest Against Colonialism and Slavery

The life-sized wooden statue of the Black Christ in St. Philip Church in Panama. Dan Lundberg/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Panama’s “Festival del Cristo Negro,” the festival of the “Black Christ,” is an important religious holiday for local Catholics. It honors a dark, life-sized wooden statue of Jesus, “Cristo Negro” – also known as “El Nazaraeno,” or “The Nazarene.”

Throughout the year, pilgrims come to pay homage to this statue of Christ carrying a cross, in its permanent home in Iglesia de San Felipe, a Roman Catholic parish church located in Portobelo, a city along the Caribbean coast of Panama.

But it is on Oct. 21 each year that the major celebration takes place. As many as 60,000 pilgrims from Portobelo and beyond travel for the festival, in which 80 men with shaved heads carry the black Christ statue on a large float through the streets of the city.

The men use a common Spanish style for solemn parades – three steps forward and two steps backward – as they move through the city streets. The night continues with music, drinking and dancing.

In my research on the relationship between Christianity, colonialism and racism, I have discovered that such festivals play a crucial role for historically oppressed peoples.

About 9% of Panama’s population claims African descent, many of whom are concentrated in Portobelo’s surrounding province of Colón. Census data from 2010 shows that over 21% of Portobelo’s population claimAfrican heritage or black identity.

To Portobelo’s inhabitants, especially those who claim African descent, the festival is more than a religious celebration. It is a form of protest against Spanish colonialism, which brought with it slavery and racism.

History of the statute

Portobelo’s black Christ statue is a fascinating artifact of Panama’s colonial history. While there is little certainty as to its origin, many scholars believe the statue arrived in Portobelo in the 17th century – a time when the Spanish dominated Central America and brought in enslaved people from Africa.

Cristo Negro. Adam Jones/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Various legends circulate in Panama as to how the black Christ got to Portobelo. Some maintain that the statue originated in Spain, others that it was locally made, or that it washed ashore miraculously.

One of the most common stories maintains that a storm forced a ship from Spain, which was delivering the statue to another city, to dock in Portobelo. Every time the ship attempted to leave, the storms would return.

Eventually, the story goes, the statue was thrown overboard. The ship was then able to depart with clear skies. Later, local fishermen recovered the statue from the sea.

The statue was placed in its current home, Iglesia de San Felipe, in the early 19th century.

Stories of miracles added to its mystique. Among the legends in circulation is one about how prayers to the black Christ spared the cityfrom a plague ravaging the region in the 18th century.

Catholicism and African identity

Since its exact origins are unknown, so are the artistic intention behind the Jesus statue. However the figure’s blackness has made it an object of particular devotion for locals of African descent.

At the time of the arrival of Cristo Negro, the majority of the Portobelo’s population was of African descent. This cultural heritage is significant to the city’s identity and traditions.

The veneration of the statue represents one of many ways that the black residents of Portobelo and the surrounding Colón region of Panama have engendered a sense of resistance to racism and slavery.

Each year around the time of Lent, local men and women across Colón – where slavery was particularly widespread – dramatize the story of self-liberated black slaves known as the Cimarrones. This reenactment is one of a series of celebrations, or “carnivals,” observed around the time of Lent by those who identify with the cultural tradition known colloquially as “Congo.” The term Congo was originally used by the Spanish colonists for anyone of African descent. It is now is used for traditions that can be traced back to the Cimarrones.

During the carnival celebration, some local people dress up as the devil, meant to represent Spanish slave masters or complicit priests. Others don the dress of the Cimarrones.

Many of the participants in both the black Christ and carnival celebrations of Panama are Catholics as well. Together they participate to bring to light the Catholic Church’s complex relationship with Spanish colonization and slavery. Many Catholic leaders in the 16th to 18th centuries justified the enslavement of Africans and the colonization of the Americas, or at least did not object to it.

A revered tradition

The different colored robes that are put on the statue of Cristo Negro. Ali EminovFlickr, CC BY-NC

Many people from throughout Panama have donated robes to clothe the statue. The colors of the robes donned by the statue varies throughout the year. Purple is reserved for the October celebrations, which likely reflects the use of purple in Catholic worship to signify suffering.

These robes draped on Panama’s black Christ are meant to representthose placed on Jesus when he was mockingly dressed in royal garb by the soldiers torturing him before his crucifixion.

Evoking this scene perhaps serves to remind the viewer of the deeper theological meaning of Jesus’s suffering as it is often understood in Christianity: Although Jesus is the Son of God prophesied to save God’s people from suffering and should thus be treated like royalty, he was tortured and executed as a common criminal. His suffering is understoodto save people from their sins.

Some pilgrims specifically come during the October festival to seek forgiveness for any sinful actions. Some wear their own purple robes, the color indicating a sign of their suffering – and, of course, that of the black Christ.

S. Kyle Johnson is a Doctoral Student in Systematic Theology, Boston College

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

People participate in a candlelight vigil near the White House to protest violence against Sikhs in 2012. AP Photo/Susan Walsh

Why Sikhs Wear a Turban and What it Means to Practice the Faith in the United States

An elderly Sikh gentleman in Northern California, 64-year-old Parmjit Singh, was recently stabbed to death while taking a walk in the evening. Authorities are still investigating the killer’s motive, but community members have asked the FBI to investigate the killing.

For many among the estimated 500,000 Sikhs in the U.S., it wouldn’t be the first time. According to the Sikh Coalition, the largest Sikh civil rights organization in North America, this is the seventh such attack on an elderly Sikh with a turban in the past eight years.

As a scholar of the tradition and a practicing Sikh myself, I have studied the harsh realities of what it means to be a Sikh in America today. I have also experienced racial slurs from a young age.

I have found there is little understanding of who exactly the Sikhs are and what they believe. So here’s a primer.

Founder of Sikhism

The founder of the Sikh tradition, Guru Nanak, was born in 1469 in the Punjab region of South Asia, which is currently split between Pakistan and the northwestern area of India. A majority of the global Sikh population still resides in Punjab on the Indian side of the border.

From a young age, Guru Nanak was disillusioned by the social inequities and religious hypocrisies he observed around him. He believed that a single divine force created the entire world and resided within it. In his belief, God was not separate from the world and watching from a distance, but fully present in every aspect of creation.

He therefore asserted that all people are equally divine and deserve to be treated as such.

To promote this vision of divine oneness and social equality, Guru Nanak created institutions and religious practices. He established community centers and places of worship, wrote his own scriptural compositions and institutionalized a system of leadership (gurus) that would carry forward his vision.

The Sikh view thus rejects all social distinctions that produce inequities, including gender, race, religion and caste, the predominant structure for social hierarchy in South Asia.

A community kitchen run by the Sikhs to provide free meals irrespective of caste, faith or religion, in the Golden Temple, in Punjab, India. shankar s., CC BY

Serving the world is a natural expression of the Sikh prayer and worship. Sikhs call this prayerful service “seva,” and it is a core part of their practice.

The Sikh identity

In the Sikh tradition, a truly religious person is one who cultivates the spiritual self while also serving the communities around them – or a saint-soldier. The saint-soldier ideal applies to women and men alike.

In this spirit, Sikh women and men maintain five articles of faith, popularly known as the five Ks. These are: kes (long, uncut hair), kara (steel bracelet), kanga (wooden comb), kirpan (small sword) and kachera (soldier-shorts).

Although little historical evidence exists to explain why these particular articles were chosen, the five Ks continue to provide the community with a collective identity, binding together individuals on the basis of a shared belief and practice. As I understand, Sikhs cherish these articles of faith as gifts from their gurus.

Turbans are an important part of the Sikh identity. Both women and men may wear turbans. Like the articles of faith, Sikhs regard their turbans as gifts given by their beloved gurus, and their meaning is deeply personal. In South Asian culture, wearing a turban typically indicated one’s social status – kings and rulers once wore turbans. The Sikh gurus adopted the turban, in part, to remind Sikhs that all humans are sovereign, royal and ultimately equal.

Sikhs in America

Today, there are approximately 30 million Sikhs worldwide, making Sikhism the world’s fifth-largest major religion.

‘A Sikh-American Journey’ parade in Pasadena, Calif. AP Photo/Michael Owen Baker

After British colonizers in India seized power of Punjab in 1849, where a majority of the Sikh community was based, Sikhs began migrating to various regions controlled by the British Empire, including Southeast Asia, East Africa and the United Kingdom itself. Based on what was available to them, Sikhs played various roles in these communities, including military service, agricultural work and railway construction.

The first Sikh community entered the United States via the West Coast during the 1890s. They began experiencing discrimination immediately upon their arrival. For instance, the first race riot targeting Sikhs took place in Bellingham, Washington, in 1907. Angry mobs of white men rounded up Sikh laborers, beat them up and forced them to leave town.

The discrimination continued over the years. For instance, when my father moved from Punjab to the United States in the 1970s, racial slurs like “Ayatollah” and “raghead” were hurled at him. It was a time when 52 American diplomats and citizens were taken captive in Iran and tension between the two countries was high. These slurs reflected the racist backlash against those who fitted the stereotypes of Iranians. Our family faced a similar racist backlash when the U.S. engaged in the Gulf War during the early 1990s.

Increase in hate crimes

The racist attacks spiked again after 9/11, particularly because many Americans did not know about the Sikh religion and may have conflated the unique Sikh appearance with popular stereotypes of what terrorists look like. News reports show that in comparison to the past decade, the rates of violence against Sikhs have surged.

Elsewhere too, Sikhs have been victims of hate crimes. An Ontario member of Parliament, Gurrattan Singh, was recently heckled with Islamophobic comments by a man who perceived Singh as a Muslim.

As a practicing Sikh, I can affirm that the Sikh commitment to the tenets of their faith, including love, service and justice, keeps them resilient in the face of hate. For these reasons, for many Sikh Americans, like myself, it is rewarding to maintain the unique Sikh identity.

SIMRAN JEET SINGH is a Henry R. Luce Post-Doctoral Fellow in Religion in International Affairs Post-Doctoral Fellow at New York University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Ashura in Syria. Tasnim News Agency, CC BY-SA

What is Ashura? How this Shiite Muslim Holiday Inspires Millions

Tens of millions of Shiite Muslims from around the world will visit Iraq on Sept. 10 this year to see the shrines of Hussain, grandson of Prophet Mohammed, and his brother Abbas on the day of “Ashura.”

This annual pilgrimage marks the 10th day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic new year. As the Islamic calendar is a lunar one, the day of Ashura changes from year to year.

Muslims visit the shrines to observe the martyrdom day of Hussain, who was killed in the desert of Karbala in today’s Iraq in A.D. 680. Shiite Muslims believe that Hussain was their third imam – a line of 12 divinely appointed spiritual and political successors.

Muharram may be an ancient festival, but as my research tracing the modern-day impact of Islamic pilgrimage shows, its meaning has changed over the centuries. What was once a commemoration of martyrdom today inspires much more, including social justice work around the globe.

Martyrdom of Hussain

The story of Muharram dates back 13 centuries, to events that followed the death of Prophet Mohammed.

After the prophet’s death in A.D. 632, a dispute emerged over who would inherit the leadership of the Muslim community and the title of caliph, or “deputy of God.” A majority of Muslims backed Abu Bakr, a close companion of the prophet, to become the first caliph. A minority wanted the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali. Those that supported his claim later came to be called Shiite Muslims.

Even if Ali was not made the caliph, Shiite Muslims would consider Ali their first imam – a leader divinely appointed by God. The title of imam would be passed on to his sons and his descendants.

Political leadership largely remained out of the hands of Shiite Imams. They would not be caliphs, but Shiites came to believe that their imam was the true leader to be followed.

By the time Ali’s second son, Hussain, came to be the third imam, divisions between the caliph and the imam had further deepened.

In A.D. 680, during the holy month of Muharram, a caliph of the Umayyad dynasty, Yazīd, ordered Hussain to pledge allegiance to him and his caliphate – a dynasty that ruled the Islamic world from A.D. 661 to 750.

Hussain refused because he believed Yazīd’s rule to be unjust and illegitimate.

His rejection resulted in a massive 10-day standoff at Karbala, in modern-day Iraq, between Umayyad’s large army and Hussain’s small band, which included his half-brother, wives, children, sisters and closest followers.

The Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. Alessandra Kocman, CC BY-NC-ND

The Umayyad army cut off food and water for Hussain and his companions. And on the day of Ashura, Hussain was brutally killed. Among the men, only Hussain’s sick son was spared. Women were unveiled – a violation of their honor as the family members of the prophet – and paraded to Damascus, the seat of Umayyad rule.

Passion plays and performances

This history is reenacted throughout the world on the day of Ashura.

In Iraq, millions of pilgrims fill the streets to visit the shrines, chanting poems of lamentation, and witness a reenactment of violence in Karbala and the capture of the women and children.

From New York and London to Hyderabad and Melbourne, thousands take part in Ashura processions carrying replicas of Hussain’s battle standard and following a white horse. This symbolizes Hussain’s riderless horse returning to the camp after his martyrdom.

Persian passion plays known as “taziyeh,” music dramas of the many martyrs and tragedies of Karbala, are performed across Iran and many other countries. Taziyeh performances are meant to evoke deep emotions of grief in the audience.

A powerful set of themes

Numerous historians and anthropologists have explored how communities across time and space have adapted the story of Karbala or the rituals around Ashūrā.

In the 16th century, a vast majority of the population across Persia, or today’s Iran, would be converted to Shiite Muslims. In this region, the passion plays evolved into a popular form of religious and artistic expression.

The character of Zainab, the Prophet Mohammed’s granddaughter, has also come to play a central role in remembrance of the Karbala story.

Scholars have drawn attention to speeches in which Zainab denounced the violence in Karbala and lauded Hussain’s “martyrdom.”

Today, Zainab is seen as a strong female model of resistance.

In the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the story of Karbala became a rallying point for opponents of the shah, who were fighting against the shah’s brutal and oppressive regime. They compared the shah to the caliph Yazīd and argued that ordinary Iranians had to stand up to an oppressor, just like Hussain had.

Zainab’s resistance to oppression helped emphasize the role of women in Islamic society.

Anthropologist Michael Fischer calls this the “Karbala paradigm” – a story that captures a powerful set of themes, including people standing up to the state and fighting for justice and morality.

Inspiring change?

Today the story of Karbala has become a powerful tool of fight for social justice in Muslim communities.

“Who is Hussain?,” a social movement with chapters in over 60 cities worldwide, carries out charitable activities and blood donations in the name of Hussain. Volunteers are encouraged to organize around events that will be meaningful in their communities and will tie into social justice issues that Hussain is believed to have fought for.

In 2018, local volunteers donated tens of thousands of bottles of water in Flint, Michigan in remembrance of Hussain and his companions, who were denied water for three days before they were killed.

As historian Yitzhak Nakash points out, the tragedy of Karbala gives Shiite Muslims a common narrative to pass on to the next generations. And commemorating it in multiple ways is an part of their unique identity.

NOORZEHRA ZAIDI is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

NEPAL: Kung Fu Nuns

This nunnery has an empowering claim to fame—it’s the only one in Nepal where the nuns practice martial arts. The nuns of the Buddhist Drukpa Order train three hours a day, and they break bricks with their bare hands. Heroes in the Himalayas, these strong women delivered supplies to hard-to-reach villages after an earthquake struck Kathmandu in 2015. The kung fu nuns have also taught self-defense classes for women and biked 14,000 miles to protest the human trafficking of women and girls.

The Netherland’s New Burqa Ban is a Sign of Hostility Towards the Dutch Muslim Community

The discriminatory law violates both religious freedom and freedom of movement.

Photo of Library Hall in the Rijksmuseum by Will van Wingerden on Unsplash. This is one of many buildings now off limits to people wearing burqas or niqabs.

Last June, the Upper House of Parliament passed a ban on face-covering garmates such as burqas and niqabs by 35 to 40 votes. The law came into effect early this month, banning those wearing such garmates from entering public places including government buildings, public transport, hospitals, and schools.

Amnesty International has released a statement calling the ban an infringement on women's rights to dress as they choose. The ban follows similar laws throughout Europe and will make the Netherlands the 6th country in the EU to ban burqas and niqabs in public buildings. The law does not apply to streets and other outdoor public spaces.

While the exact number of women impacted by the law is unclear, the Guardian writes that according to a 2009 study by University of Amsterdam professor Annelies Moors, an estimated 100 women routinely wear a face veil and less than 400 sometimes wear a veil. Moors, a critic of the bill, states that it has the power to interfere with women's daily lives. It restricts their access to hospitals, police stations, and schools, preventing them from accessing education, reporting crimes, and other necessary abilities.

While the Dutch government has stated that the law is a non-discriminatory effort to ensure public safety, the far-right has been quick to cite the ban as a party victory. "Finally, 13 years after a majority in the Dutch Parliament voted in favor of my motion to ban the burqa, it became law yesterday!" Geert Wilders of the far-right Freedom Party tweeted last June including the telling hashtags #stopislam #deislamize.

Al Jazeera writes that Wilders hopes to go even further with the ban."I believe we should now try to take it to the next step," he told the Associated Press. "The next step to make it sure that the headscarf could be banned in the Netherlands as well."

Under the new law, someone wearing a banned clothing item must either remove it, or face a fine from 150 to 415 euro. Police and transport officials, however, have expressed a reluctance to comply with the ban.

After a statement from the police saying that enforcing the law is not a priority for them, transportation authorities announced that they would not be enforcing the law as police assistance would not be readily available.

“The police have told us the ban is not a priority and that therefore they will not be able to respond inside the usual 30 minutes, if at all,” Pedro Peters, a spokesman for the Netherlands transport network told the Guardian. “This means that if a person wearing a burqa or a niqab is challenged trying to use a service, our staff will have no police backup to adjudicate on what they should do. It is not up to transport workers to impose the law and hand out fines.”

Hospitals also stated that they would continue to treat patients regardless of clothing.

The Muslim community has rallied to support those affected by the law. The Nida (Rotterdam’s islamic party) has stated that it will pay all fines imposed on those wearing niqabs. The party even created a community account where people can donate money to be used for fines. Algerian activist Rachid Nekkaz also offered to cover fines.

Despite the lack of enforcement surrounding the ban, its existence alone is a sign of hostility towards the Dutch Muslim community. According to Al Jazeera, Nourdin el-Ouali, who leads the Nida Party, called the ban a “serious violation” of religious freedom and freedom of movement, and warned that it will have far-reaching consequences.

EMMA BRUCE is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. While not writing she explores the nearest museums, reads poetry, and takes classes at her local dance studio. She is passionate about sustainable travel and can't wait to see where life will take her.

People of Xinjiang. Peter Chou Kee Liu. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

China is Putting Muslims in Concentration Camps Because of an “Ideological Illness”

According to a UN report, China has declared Islam an “ideological illness”. One UN spokesperson claims there are approximately over a million Muslims currently in these camps. The UN report states “the evidence indicated that most of the detentions were taking place outside the criminal justice system, and targeted specifically Uyghur and other Muslim minorities, such as Kazakh”. But why is this happening? In the words of the Official Chinese Communist Party, “Members of the public who have been chosen for re-education have been infected by an ideological illness. They have been infected with religious extremism and violent terrorist ideology, and therefore they must seek treatment from a hospital as an inpatient”. The region of Xinjiang, in recent years, has faced attacks from extremist groups and because of this, have targeted the entire Uighur community in Xinjiang to prevent them from being further “infected by religious extremism and a violent terrorism disease.”

The region of Xinjiang is a highly populated by the “Turkic-speaking Muslim Uighur minority, who make up about eight million of its 19 million people”, according to a BBC article profiling the region. With the population being highly Muslim, the Chinese government has profiled that area in a subtle racist attempt to force the people of the area to renounce Islam and their practices. In a statement from the Communist Party, they state that “in order to provide treatment to people who are infected with ideological illnesses and to ensure the effectiveness of the treatment, the Autonomous Regional Party Committee decided to set up re-education camps in all regions, organizing special staff to teach state and provincial laws, regulations, the party’s ethnic and religious policies, and various other guidelines”. Furthermore, they say, “At the end of re-education, the infected members of the public return to a healthy ideological state of mind, which guarantees them the ability to live a beautiful happy life with their families”. It is disturbing to read words such as “disease” and “those infected” when it is in regards to innocent Uiguhr individuals. Using such diction creates a harmful and discriminatory connotation that the Uighur community is “sick” and “infectious”, a dangerously false narrative.

Although the camps have the intention of “[fighting] separatism and Islamic extremism”, they stem from a fear of an uprising in the Xinjiang area and has become a prejudice and gross abuse of human rights. Many of the people who were able to leave the concentration camps now are facing psychological ramifications and a complete lack of faith in the country that they are living. The camps are supposedly supposed to help threats and protect the people, yet they are harming them instead.

In many interviews from those who were in the concentration camp, they have mentioned that the “re-education” forces them to renounce Islam, renounce the Holy Quran, admit that the Uighur culture is backward in comparison to the Communist Party, and if the detainees refuse to cooperate, they are punished harshly. Some punishments include them not being fed, solitary confinement, or physical beatings. Recently, it has come out that there has been a death in one of the camps. A Uighur writer Nurmuhammad Tohti, died at the age of 70 because "he had been denied treatment for diabetes and heart disease, and was only released once his medical condition meant he had become incapacitated", according to his granddaughter, Zorigul. But even with the criticism and the death, the Chinese government still does not believe what they are doing is wrong.

China Daily, a popular media outlet, claimed that “Western critics of China's policies on human rights and religious freedom in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region seem to be divorced from the realities of the situation.” They stand in defense of their practices rather than understand how harmful they are and how they are creating a dogmatic perspective.

It is concerning to see how fear has created a ripple of harmful decisions and gross infringements on human rights. There is no reason for an entire community to reap the consequences of extremists actions when they are the innocents.

OLIVIA HAMMOND is an undergraduate at Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts. She studies Creative Writing, with minors in Sociology/Anthropology and Marketing. She has travelled to seven different countries, most recently studying abroad this past summer in the Netherlands. She has a passion for words, traveling, and learning in any form.

Above is a collection of drug paraphernalia, including syringes and a cigarette. Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte began a war on drugs in 2016, and Sister Cresencia Lucero, who died May 15, fought against it as a human rights advocate. Matthew Rader. CC0.

Filipino Human Rights Advocate Sister Cresencia Lucero Honored

Crescencia Lucero of the Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, also known as Sister Cres, passed away May 15 from a stroke. She was attending a meeting on human rights in Jakarta, Indonesia with the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (Forum-Asia) at the time, a cause she devoted much of her life to. Lucero was 77.

Lucero was a major figure in the Filipino human rights community. She headed the Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines' Justice and Peace and Integrity of Creation ministry (AMRSP). Lucero also worked with several human rights organizations with other religious leaders, such as the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA).

AMRSP includes hundreds of religious congregations, for both men and women. The organization as a whole works with various social issues and coordinates congregations, lay groups, and other organizations’ combined actions on those same social issues, including poverty, human trafficking, and labor rights, among others. In October 2015, it organized an ecological walk for justice. The organization was also able to arrange a justice march for the climate.

Rodrigo Duterte began the 2016 war against drugs with his presidential campaign, in which he urged people to kill drug addicts. After winning the presidency, he launched his drug policy, aiming to neutralize illegal drug personalities. Following his inauguration, Duterte said he would order police to adopt a shoot-to-kill policy. Duterte also released lists of people who were allegedly part of the illegal drug trade, which often included politicians. Since 2016, over 12,000 Filipino people have been killed due to the war on drugs, according to Human Rights Watch. At least 2,500 deaths were due to police. HRW has also shown that police reports show killings to be justified as self-defense. Lucero would stay awake nights to monitor and visit places where drug dealers had been killed. Her organizations referred people to drug rehab centers, though there weren’t very many centers or treatments at the time. Her organizations also opened churches as sanctuaries to victims whose rights were violated, including children who witnessed or were injured during drug-related shootings and raids. The drug war continues to be a major human rights issue, and in November 2018, three police officers were found guilty for the murder of a 17-year-old; the sentence was seen as a rare moment of responsibility.

Lucero spoke of the issue in October 2016, in an interview with Global Sisters Report: “But then when the killings started and those who were targeted were the small people, the poor, especially in the urban poor communities—there's no more distinction between drug pushers and drug users. The drug pushers are also users, but most of those being killed now are the users who are pushed into it because of the situation with poverty. If you look into the families and communities of those who are most victimized, it's the poor ones.

Redemptorist priest Oliver Castor, spokesman of the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, said that during the martial law years (1972-1981, specifically), Sister Lucero was one of the people who assisted in providing safe haven for people. AMRSP opened convents and churches as sanctuaries for those who were in need, whether that meant families, extended families, or even grandparents. Even now, there is still a facilitation desk at AMRSP for sanctuaries, though the last case was in 2008.

During that same period, Lucero was the co-chair of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines, which assisted political prisoners with moral, spiritual, material, and legal help when then-President Marcos banned organizations. The task force continued after marital law was lifted because of the vast number of political prisoners who remained. In 2014, Lucero said in an interview with Global Sisters Report that they have helped around 100 detainees a year. She made it clear that their main thought was to be supportive to the families of the victims.

When asked how she continues doing her work in the same interview, Lucero said, “I tell the Lord every night I am ready any time, “Take me. You have blessed me with so many opportunities.” So when I have to travel, I put my things in order, even my bedroom. Anything can happen.”

A number of ecunemical gatherings were held in Lucero’s honor in Manila the week of May 24. Her tireless work with human rights, the poor, and protecting people against martial law mark her as a person who truly felt for and worked with humanity. Father Toledo, a Franciscan, put it well when he said to UCA News that Sister Lucero "faithfully performed the duties of a true Franciscan and a true Christian."\

NOEMI ARELLANO-SUMMER is a journalist and writer living in Boston, MA. She is a voracious reader and has a fondness for history and art. She is currently at work on her first novel and wants to eventually take a trip across Europe.

Women pray at a mosque during the first day of the holy fasting month of Ramadan on May 6 in Bali, Indonesia. AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati

What Ramadan Means to Muslims: 4 Essential Reads

During the month of Ramadan, Muslims around the world will not eat or drink from dawn to sunset. Muslims believe that the sacred text of Quran was first revealed to Prophet Muhammad in the final 10 nights of Ramadan.

Here are four ways to understand what Ramadan means for Muslims, and in particular for American Muslims.

1. Importance of Ramadan

Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam. Each pillar denotes an obligation of living a good Muslim life. The others include reciting the Muslim profession of faith, daily prayer, giving alms to the poor and making a pilgrimage to Mecca.

Mohammad Hassan Khalil, associate professor of religious studies and director of the Muslim Studies Program at Michigan State University, explains that the Quran states that fasting was prescribed for Muslims so that they could be conscious of God. He writes,

“By abstaining from things that people tend to take for granted (such as water), it is believed, one may be moved to reflect on the purpose of life and grow closer to the creator and sustainer of all existence.”

He also notes that for many Muslims, fasting is a spiritual act that allows them to understand the condition of the poor and thus develop more empathy.

2. Halal food

During Ramadan, when breaking fast, Muslims will eat only foods that are permissible under Islamic law. The Arabic word for such foods, writes religion scholar Myriam Renaud, is “halal.”

Renaud explains that Islamic law draws on three religious sources to determine which foods are halal. These include “passages in the Quran, the sayings and customs of the Prophet Muhammad, which were written down by his followers and are called ‘Hadith’ and rulings by recognized religious scholars.”

In the United States, some states such as California, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey and Texas restrict the use of halal label for foods that meet Islamic religious requirements. Various Muslim organizations also oversee the production and certification of halal products, she writes.

3. Puerto Rican Muslims

In Puerto Rico, where many have been reverting to the religion of their ancestors – Islam – Ramadan could mean combining their identity as a Puerto Rican and as a Muslim.

Ken Chitwood, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Florida, explainsthat Muslims first came to Puerto Rico as part of the transatlantic colonial exchange between Spain, Portugal and the New World. There is evidence, he writes, of the first Muslims arriving somewhere around the 16th century.

In his research, he found Puerto Rican Muslims in search of a “Boricua Islamidad” – “a unique Puerto Rican Muslim identity that resists complete assimilation to Arab cultural norms even as it reimagines and expands what it means to be Puerto Rican and a Muslim.”

He saw the expression of this identity in the food as Puerto Rican Muslims broke fast – “a light Puerto Rican meal of tostones – twice-fried plantains.”

4. Jefferson’s Quran

Ramadan dinner at White House in 2018. AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

With an estimated 3.3 million American Muslims, Ramadan is celebrated each year at the White House, except for one year in 2017. Scholar Denise A. Spellberg explains that the tradition was started by Hillary Clinton when she was the first lady.

She writes that “Islam’s presence in North America dates to the founding of the nation, and even earlier.” Among the most notable of the key American Founding Fathers who demonstrated an interest in the Muslim faith was Thomas Jefferson. Her research shows that Jefferson bought a copy of the Quran as a 22-year-old law student in Williamsburg, Virginia, 11 years before drafting the Declaration of Independence. And as she says,

“The purchase is symbolic of a longer historical connection between American and Islamic worlds, and a more inclusive view of the nation’s early, robust view of religious pluralism.”

KALPANA JAIN is a Senior Religion and Ethics Editor.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Conservative lawmakers in dozens of U.S. states have raised fears that Islamic fundamentalists want to impose Sharia on Americans. Reuters/David Ryder

Don’t Blame Sharia for Islamic Extremism – Blame Colonialism

Warning that Islamic extremists want to impose fundamentalist religious rule in American communities, right-wing lawmakers in dozens of U.S. states have tried banning Sharia, an Arabic term often understood to mean Islamic law.

These political debates – which cite terrorism and political violence in the Middle East to argue that Islam is incompatible with modern society – reinforce stereotypes that the Muslim world is uncivilized.

They also reflect ignorance of Sharia, which is not a strict legal code. Sharia means “path” or “way”: It is a broad set of values and ethical principles drawn from the Quran – Islam’s holy book – and the life of the Prophet Muhammad. As such, different people and governments may interpret Sharia differently.

Still, this is not the first time that the world has tried to figure out where Sharia fits into the global order.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when Great Britain, France and other European powers relinquished their colonies in the Middle East, Africa and Asia, leaders of newly sovereign Muslim-majority countries faced a decision of enormous consequence: Should they build their governments on Islamic religious values or embrace the European laws inherited from colonial rule?

The big debate

Invariably, my historical research shows, political leaders of these young countries chose to keep their colonial justice systems rather than impose religious law.

Newly independent Sudan, Nigeria, Pakistan and Somalia, among other places, all confined the application of Sharia to marital and inheritance disputes within Muslim families, just as their colonial administrators had done. The remainder of their legal systems would continue to be based on European law.

France, Italy and the United Kingdom imposed their legal systems onto Muslim-majority territories they colonized. CIA Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, CC BY

To understand why they chose this course, I researched the decision-making process in Sudan, the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from the British, in 1956.

In the national archives and libraries of the Sudanese capital Khartoum, and in interviews with Sudanese lawyers and officials, I discovered that leading judges, politicians and intellectuals actually pushed for Sudan to become a democratic Islamic state.

They envisioned a progressive legal system consistent with Islamic faithprinciples, one where all citizens – irrespective of religion, race or ethnicity – could practice their religious beliefs freely and openly.

“The People are equal like the teeth of a comb,” wrote Sudan’s soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Hassan Muddathir in 1956, quoting the Prophet Muhammad, in an official memorandum I found archived in Khartoum’s Sudan Library. “An Arab is no better than a Persian, and the White is no better than the Black.”

Sudan’s post-colonial leadership, however, rejected those calls. They chose to keep the English common law tradition as the law of the land.

Why keep the laws of the oppressor?

My research identifies three reasons why early Sudan sidelined Sharia: politics, pragmatism and demography.

Rivalries between political parties in post-colonial Sudan led to parliamentary stalemate, which made it difficult to pass meaningful legislation. So Sudan simply maintained the colonial laws already on the books.

There were practical reasons for maintaining English common law, too.

Sudanese judges had been trained by British colonial officials. So they continued to apply English common law principles to the disputes they heard in their courtrooms.

Sudan’s founding fathers faced urgent challenges, such as creating the economy, establishing foreign trade and ending civil war. They felt it was simply not sensible to overhaul the rather smooth-running governance system in Khartoum.

The Sudanese city of Suakim in 1884 or 1885, just prior to British colonial rule. The National Archives UK

The continued use of colonial law after independence also reflected Sudan’s ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity.

Then, as now, Sudanese citizens spoke many languages and belonged to dozens of ethnic groups. At the time of Sudan’s independence, people practicing Sunni and Sufi traditions of Islam lived largely in northern Sudan. Christianity was an important faith in southern Sudan.

Sudan’s diversity of faith communities meant that maintaining a foreign legal system – English common law – was less controversial than choosing whose version of Sharia to adopt.

Why extremists triumphed

My research uncovers how today’s instability across the Middle East and North Africa is, in part, a consequence of these post-colonial decisions to reject Sharia.

In maintaining colonial legal systems, Sudan and other Muslim-majority countries that followed a similar path appeased Western world powers, which were pushing their former colonies toward secularism.

But they avoided resolving tough questions about religious identity and the law. That created a disconnect between the people and their governments.

In the long run, that disconnect helped fuel unrest among some citizens of deep faith, leading to sectarian calls to unite religion and the state once and for all. In Iran, Saudi Arabia and parts of Somalia and Nigeria, these interpretations triumphed, imposing extremist versions of Sharia over millions of people.

In other words, Muslim-majority countries stunted the democratic potential of Sharia by rejecting it as a mainstream legal concept in the 1950s and 1960s, leaving Sharia in the hands of extremists.

But there is no inherent tension between Sharia, human rights and the rule of law. Like any use of religion in politics, Sharia’s application depends on who is using it – and why.

Leaders of places like Saudi Arabia and Brunei have chosen to restrict women’s freedom and minority rights. But many scholars of Islam and grassroots organizations interpret Sharia as a flexible, rights-oriented and equality-minded ethical order.

Women in Saudi Arabia have campaigned for gender equality, including the right to drive cars. Reuters/Faisal Nasser

Religion and the law worldwide

Religion is woven into the legal fabric of many post-colonial nations, with varying consequences for democracy and stability.

After its 1948 founding, Israel debated the role of Jewish law in Israeli society. Ultimately, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and his allies opted for a mixed legal system that combined Jewish law with English common law.

In Latin America, the Catholicism imposed by Spanish conquistadors underpins laws restricting abortion, divorce and gay rights.

And throughout the 19th century, judges in the U.S. regularly invoked the legal maxim that “Christianity is part of the common law.” Legislators still routinely invoke their Christian faith when supporting or opposing a given law.

Political extremism and human rights abuses that occur in those places are rarely understood as inherent flaws of these religions.

When it comes to Muslim-majority countries, however, Sharia takes the blame for regressive laws – not the people who pass those policies in the name of religion.

Fundamentalism and violence, in other words, are a post-colonial problem – not a religious inevitability.

For the Muslim world, finding a system of government that reflects Islamic values while promoting democracy will not be easy after more than 50 years of failed secular rule. But building peace may demand it.

MARK FATHI MASSOUD is an Associate Professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Inside the Network of Mormon Moms Fighting for Their LGBTQ Children

Growing up in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints can be an isolating experience for LGBTQ+ youth. Current Mormon doctrine doesn’t have a place for those who identify as LGBTQ+, or any guidance or support for young adults navigating their sexuality. Many face unforgiving ideologies that teach them to be celibate, or to “pray the gay away.” Furthermore, the state of Utah has the highest suicide rate among children ages 10-17, a statistic that is especially alarming to parents. Within this culture are the Mama Dragons, a fiercely loving support group of mothers that provides open ears and open arms to LGBTQ+ youth and families in the Mormon community. Comprised of Mormon, post-Mormon and never-Mormon women, the support group offers mothers of LGBTQ+ children an outlet and a community. Together, this grassroots group of mothers is breathing fire to protect their kids, writing a new chapter in a community of faith.

In France, This Chapel Rises From a Volcano

If you want to visit the Chapel of Saint-Michel d'Aiguilhe, aka, “Saint Michael of the Needle,” you’ll have to climb up—way up. Located in France, the chapel is perched atop a distinct volcanic plug rising nearly 300 feet in the air. Dedicated to Michael the Archangel, the church was commissioned in 951 by a bishop who wanted to commemorate his 1,000-mile journey back from the Pyrenees Mountains. Today, thousands of visitors make the trek up 268 steps to witness the chapel and its stunning panoramic views.