After nearly one million Russian men fled conscription in 2022, the countries that received them are still grappling with the impacts of this influx three years later.

Read MoreRussian Poets and the Risk of Resistance

Kennedy Kiser

From public readings to prison cells, Russian poets are paying the price for speaking against the war.

Protesters march in Moscow against repression and fabricated charges. DonSimon. CC0.

“Kill me, militiaman!

You’ve already tasted blood!

You’ve seen how battle-ready brothers

Dig mass graves for the brotherly masses.

You’ll turn on the television—you’ll lose it,

Self-control has never been your strong suit.”

— Artyom Kamardin, “Kill Me, Militiaman”

In December 2023, Russian poet Artyon Kamardin was sentenced to seven years in prison for reciting anti-war verses during the public “Mayakovsky Readings” in Moscow. Fellow poet Yegor Shtovba, who performed at the same event, received a sentence of five and a half years. Kamardin was reportedly beaten and sexually assaulted during his arrest for reciting poetry in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Daria Serenko at the Moscow International Book Fair in 2019. Sergey Leschina. CC BY 4.0.

Their cases are not isolated. In April 2024, feminist poet and activist Daria Serenko was added to Russia’s federal wanted list. Known for combining poetry with political action, Serenko has faced years of harassment. Her arrest warrant, however, marked a shift in the state’s approach. Where once artists were threatened, they are now hunted.

Literature has long played a role in Russian resistance. During the Soviet era, banned texts circulated underground through samizdat networks. Today, Telegram channels and independent journals continue that tradition, sharing poetry that challenges state narratives. But the stakes are now much higher. Poets are not just being silenced; they are being criminalized. The penalties include imprisonment, forced exile and public brutality.

At the center of this increased repression is the state’s fear of language itself. Poetry distills dissent into a form that is emotionally direct and difficult to contain. It spreads quickly, often through digital platforms, in defiance of Russia’s 2022 censorship laws. Unlike journalism or political commentary, verse can bypass logic and speak directly to the reader’s gut. As poet Osip Mandelstam once wrote, “Only in Russia is poetry respected — it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?”

This crackdown is not limited to well-known names. Emerging writers, students and performers with modest online followings have also been detained or investigated for speech-related offenses. In some cases, posting a poem on VKontakte, Russia’s largest social network, has led to criminal charges. The line between art and activism has been effectively erased, especially for those who oppose the war.

International literary organizations have responded by offering emergency grants, publication platforms and legal aid. PEN International, Freemuse and countless other organizations have condemned Russia’s actions, calling for the immediate release of detained artists. Yet the risks persist. For many Russian writers, exile is the only path to safety, though it often comes with the painful cost of losing direct access to their audiences.

Repressing writers like Kamardin, Shtovba and Serenko reveals a broader strategy: to eliminate not just protest but the imagination of a different future. By imprisoning poets, the government also suppresses the potential for alternative visions of the world.

Still, Russian poetry persists. In exile, through online platforms and underground readings, writers continue to speak out. In a regime that fears language, each poem becomes an act of resistance.

GET INVOLVED:

These organizations offer support to writers and artists facing political persecution. From legal aid to international advocacy, their work helps protect freedom of expression and document human rights abuses. Getting involved means helping preserve creative resistance in some of the world’s most repressive environments.

To learn more about PEN International, click here.

To learn more about Freemuse, click here.

To learn more about Memorial International, click here.

Kennedy Kiser

Kennedy is an English and Comparative Literature major at UNC Chapel Hill. She’s interested in storytelling, digital media, and narrative design. Outside of class, she writes fiction and explores visual culture through film and games. She hopes to pursue a PhD and eventually teach literature!

Noon Against Putin: Russian Citizens Continue Navalny’s Mission

In Russia, protests in opposition to Putin’s rule continue despite the death of Alexei Navalny.

The late Alexei Navalny. Mitya Aleshkovskiy. CC BY-SA 4.0

On February 16, 2024, Alexei Navalny, outspoken critic of Vladimir Putin and major activist in Russian domestic politics, died in a Russian prison. On March 17, 2024, believers in Navalny’s vision took the next step in opposition to the president.

Despite his death, Navalny’s anti-Putin rhetoric continues to echo through the streets of Moscow. On the final day of the 2024 Russian presidential election, groups of silent protestors gathered at polling places across the country at exactly twelve o'clock noon in a demonstration dubbed “Noon Against Putin.” The plan had been endorsed by Navalny prior to his death, and the call was taken up afterwards by his widow, Yulia Navalnaya, via a video on YouTube in the days before the election.

The demonstrators voiced their disapproval of the unfair elections by either writing in Navalny’s name on their ballots, invalidating their vote, or simply leaving without voting at all. Around the world, Russian citizens also formed silent queues at embassies in Berlin and London, standing in solidarity with the demonstrators in Siberia and Moscow. Many also took to social media to decry what they called an unfair and rigged election, denying the Kremlin’s repeated claims that their president is always democratically chosen.

Protestors outside of a polling place in Moscow. Konopeg, CC0

Navalny was one of the few Russian citizens willing to outright oppose Vladimir Putin’s rule. He was arrested several times for leading protests against corruption in the Kremlin and eventually joined a centrist political party to work towards fair and just elections, among other humanitarian improvements in the daily lives of the Russian people. Navalny’s death in a Russian prison in the Arctic sparked outcry worldwide, with many world leaders accusing Putin of direct involvement.

A procession outside the Russian Embassy in Berlin. A.Savin, Free Art License

“Noon Against Putin” was carried out with the knowledge that some arrests were inevitable. The demonstration ended with at least 60 citizens imprisoned and 15 criminal charges filed. Not only did the people gathering at the ballot boxes understand that their demonstration would not change the election, but they also came in spite of the laundry list of potential punishments from the authorities. The threats of imprisonment, and possibly death in captivity, hang over the heads of any Russian citizen who speaks out against the Kremlin. But the community that Navalny has built seems unafraid of these consequences. Even though Putin was still reelected, this brief and solemn display of unity among the Russian people shows that even without their vocal leader, the anti-Putin masses are still here, and are still willing to show their disapproval.

The Kremlin, and thus Vladimir Putin, still holds complete control over Russia and its government, but the forward momentum that these protestors represent, no matter how small it may appear now, suggests a potential shift in the balance of power. In the past, Russian citizens have had little choice but to put their heads down and keep moving forward. Today, Navalny’s memory has spurred those same citizens to take action towards a vision of change.

Ryan Livingston

Ryan is a senior at The College of New Jersey, majoring in English and minoring in marketing. Since a young age, Ryan has been passionate about human rights and environmental action and uses his writing to educate wherever he can. He hopes to pursue a career in professional writing and spread his message even further.

Yakutia: One of the Coldest Places on Earth

This Russian region experiences temperatures as low as -70F and its residents live drastically differently than people who live in warmer climes.

A village in Yakutia during the winter. @simoncroberts. Instagram.

It is seven AM. The sun hasn’t risen yet, but you’ve already gathered enough wood to heat your house for 9 months straight, in anticipation of the severe climate outside. You head to the back shed to grab the ice you harvested last November and put it in a giant tub of water to melt, ensuring that your family has something to drink when the water pipes will freeze. Now it’s time to make breakfast and wake your child up for school — because even though winter has finally arrived it’s warmer than -65 degrees Fahrenheit, which means it is safe to go outside.

This is how residents of the northern reaches of the Sakha Republic, common name Yakutia, live during the long winter months. Yakutia is located in Russia and is home to some of the coldest continuously inhabited places in the world. In villages like Oymyakon, located in the far north, the sun doesn’t rise until approximately 9am and sets at 2:15pm, meaning students have to walk to and from school in darkness.

Ten minutes in the cold, fresh air is enough to cause fatigue, stinging pain in any of the exposed parts of your face, and long-lasting aches in the fingers and toes. This is why many houses in the region are made of wood and built to withstand the extreme temperatures by filling every gap with oakum, a sealant made from plant fibers and tar, or even just the abundant snow, although the cold still finds its way through at times.

The Yakut people have learned to be productive in these conditions. Most men in the Republic’s far north have traditional jobs like cattle ranching, hunting, or making crafts, living lives that hardly resemble those of urban Russians. Knife-making plays an important role in the Yakut culture, with the blades known around the world for their strength and beauty.

Summer in a Yakutian village. @Kiun B. YouTube.

When summer comes around, Yakutia becomes a completely different place. While winter temperatures can plunge down to -70 degrees Fahrenheit, in the dog days of summer the weather can get to around 86 to 95 degrees, particularly at the end of July. Summers may be short-lived — only lasting 2.5 months — but it is also the busiest time of the year for Yakut people.

It is crucial to harvest berries before the frost sets in if one wants to eat fruit during the winter., A failure to harvest the hay needed to feed the cattle in time can lead families to lose their valuable livestock.

But with hard work comes a refreshing reward. During the summer, Yakutia turns from a snowy kingdom into a lush meadow full of dense forests. Many Yakuts take advantage of the balmy heat, and head straight to the nearest lake for a swim.

Yakutia is often called the land of rivers and lakes. There are over 700,000 rivers and 800,000 lakes that are rich with aquatic life, which is the perfect opportunity for Yakut people to stock up on food for the winter months.

Although Yakutia is by no means a popular tourist destination, the region is gaining more attention on YouTube and has fascinated viewers around the world. With increased visibility facilitated by modern communications technology , it will be no surprise if curious minds begin to pay attention to Yakutia.

Michelle Tian

Michelle is a senior at Boston University, majoring in journalism and minoring in philosophy. Her parents are first-generation immigrants from China, so her love for different cultures and traveling came naturally at a young age. After graduation, she hopes to continue sharing important messages through her work.

9 Beautiful Houses of Worship Around the World

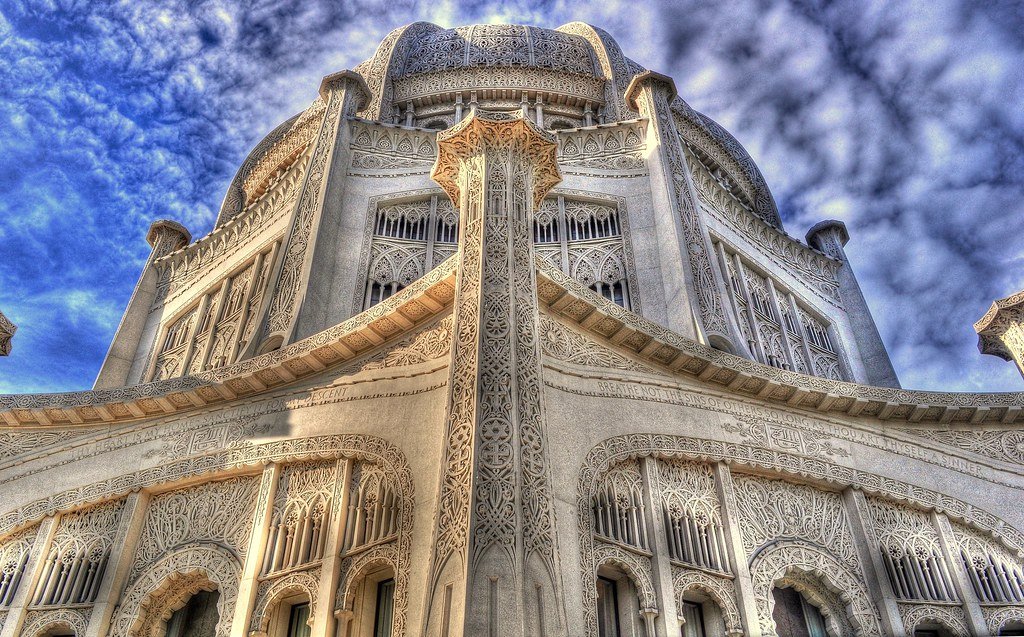

Different religions have different ways of showcasing their houses of faith.

For many centuries across the globe, people have built houses of faith to honor the higher power(s) they worship. Below is a list of different architectural representations of these sacred spaces.

1. Borgund Stave Church

Borgund, Norway

The portrayal of dragon heads on the roof of the Borgund Stave Church in Norway was built to ward off spirits in 1180. The church was dedicated to Apostle Andrew and has been incredibly preserved. The medieval church received certification in 2010 for being an environmental lighthouse. The church is set to reopen to visitors on April 15.

2. Golden Temple

Amritsar, India

Named the holiest temple in the Sikh faith, the Golden Temple’s upper floors are covered in 750 kilos of pure gold. It was built by Guru Arjan in 1604 and is located in the Northwest of India, near the border of Pakistan. It is said that the waters surrounding the temple in the river Ganga cleanse one’s bad karma when taking a dip. It is visited by 100,000 worshippers daily.

3. Hallgrímskirkja

Reykjavik, Iceland

This Lutheran Icelandic church was built by architect Guðjón Samúelsson and, at 240 feet, stands as the tallest building in the capital and the second tallest in all of Iceland. The design is influenced by the country's volcanoes and the natural surroundings that inhabit the nation. Visible from almost any point in the city, the church is known as one of Iceland’s landmarks and largest church.

4. Kizhi Pogost

Kizhi Island, Russia

Kizhi Pogost. Alexxx Malev. CC BY-NC 2.0

Set on Kizhi Island in Russia’s Lake Onega, Kizhi Pogost is a UNESCO World Heritage site consisting of two wooden churches and a bell tower built in 1714. What makes this an incredible architectural structure is that it was made completely of wood, with no metal or nails involved. Today, the churches are an open air museum.

5. Wat Rong Khun

Chiang Rai Province, Thailand

Designed by Thai visual artist Chalermchai Kositpipat, Wat Rong Khun (also known as The White Temple) was created to honor Buddha’s purity. There are many intricate details in the space, including carvings of monkeys, people and hands among other things. Today, Kositpipat has only completed three of the nine buildings he has plans for. The temple entrance cost is $1.50, Kositpipat will not accept more because he does not want large donors to influence his art. The temple is being run by a team of volunteers.

6. Las Lajas Sanctuary

Ipiales, Colombia

Las Lajas Sanctuary. BORIS Gt. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Located less than seven miles from the Ecuadorian border, Las Lajas Sanctuary sits over the Guaitara River. The Roman Catholic basilica has three iconic features. First, the bridge has statues of angels playing instruments on each side. The second is the stained glass by Italian artist Walter Wolf. Lastly, there is an image of the Virgin Mary painted on the back stone wall. The neo-Gothic basilica is surrounded by lush vegetation and was named the most beautiful church in 2015 by The Telegraph.

7. Great Mosque of Djenné

Djenné, Mali

Great Mosque of Djenné. Mission de l'ONU au Mali. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Globally known as an example of Sudano-Sahelian architecture and one of Africa’s most famous structures, the Great Mosque of Djenné was built in 1907 from mud and brick, which needs regular replastering to keep its form. Today, the Great Mosque is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a sacred destination for Muslims.

8. Jubilee Synagogue

Prague, Czech Republic

Jubilee Synagogue. BORIS G. CC BY 2.0

The colorful and intricate Jewish Jubilee Synagogue, also known as the Jerusalem Street Synagogue, was built in 1906 by architect Wilhelm Stiassny to commemorate the Emperor Franz Joseph I’s ascension to the throne. A preserved organ by composer Emanuel Stephen Peter is played for visitors. Today, it is open to the public and used for Orthodox prayer services.

9. Szeged Synagogue

Szeged, Hungary

New Synagogue. Emmanuel Dyan. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The second largest synagogue in Hungary, Szeged Synagogue merges Art Nouveau with Gothic, Moorish, Byzantine, Roman and Baroque interior design. The sanctuary’s seating faces a Torah ark made with wood from the banks of the Nile River. The triumphal arch of the building displays the biblical commandment, “Love your neighbor as yourself" in both Hebrew and Hungarian.

10. Temple of Heaven

Beijing, China

Temple of Heaven in Beijing. Fabio Achilli. CC BY 2.0

An imperial sacrificial altar, the Temple of Heaven in Dongcheng District, Beijing is considered the “supreme achievement of traditional Chinese architecture.” It is 273 acres and located in a large park, measuring 38 meters high and 30 meters in diameter, built on three levels of marble stones. It was completed during the Ming dynasty in 1420 and used to pray for harvest and for worship. In 1998, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Jennifer Sung

Jennifer is a Communications Studies graduate based in Los Angeles. She grew up traveling with her dad and that is where her love for travel stems from. You can find her serving the community at her church, Fearless LA or planning her next trip overseas. She hopes to be involved in international humanitarian work one day.

LGBTQ+ Activists Fight Anti-Gay Hate in Siberia

In the Siberian tundra, queer folks face conservative attitudes, constant harassment and violence. As a result, the region’s few LGBTQ+ activists struggle to meet their community’s needs.

A small show of support in Siberia. reassure. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

To this day, Yevgeniy Glebov doesn’t know how the two strangers found his address. Secure in his apartment, he heard a knock at the door. He opened it. They asked, “Aren’t you that gay activist?”

Yevgeniy needed to go to the hospital to recover from his injuries. After he reported the assault, the police closed the case without looking for a suspect. He expected little else from the authorities in Irkutsk Oblast, the Russian federal subject deep in Siberia where he lives and works. His NGO “Time to Act” provides legal, psychological and HIV prevention resources for the region’s LGBTQ+ community. However, this work also puts a target on his back. Advocating for gay rights is mostly a thankless job, demanding secrecy. For most LGBTQ+ Russians, it’s safer inside the closet than out.

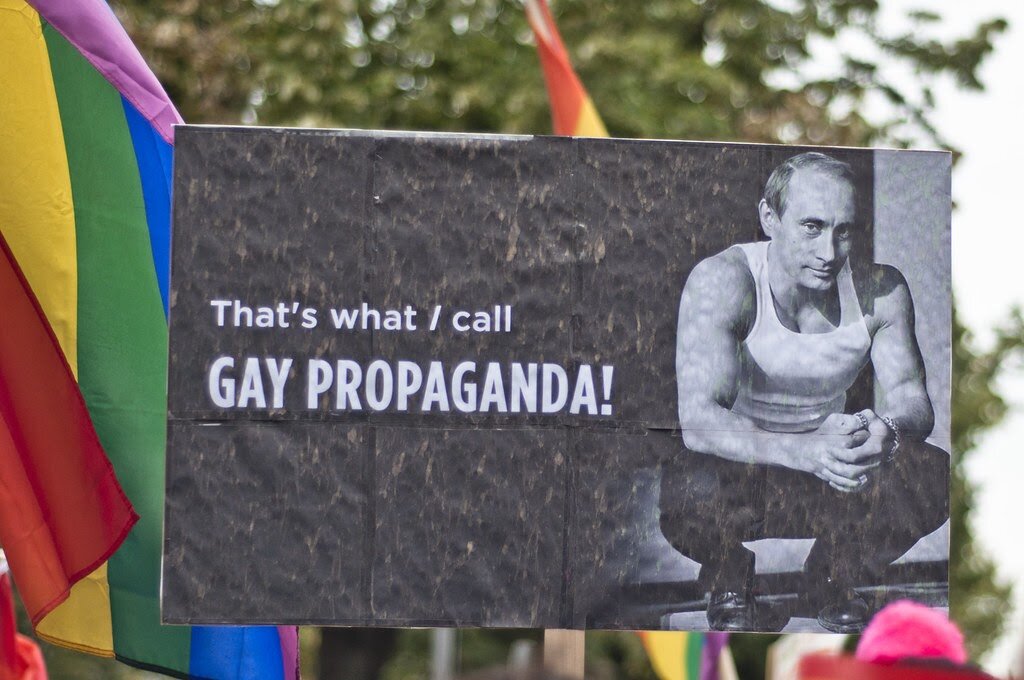

Gay pride hasn’t yet reached the mainstream in Russia. Homophobia runs rampant in Russian society and riddles the country’s laws. Article 148 of the Russian criminal code gives prosecutors the license to claim any violation of religious practice as a crime, giving them a cudgel against gay rights groups. In 2013, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin signed into the law a ban on “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations” designed to prevent children from viewing or learning about anything homosexual. These laws reflect widespread disdain and discrimination against queer folks. The bill passed the State Duma with unanimous support.

Anti-homophobia demonstration in Russia. Marco Fieber. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Homophobia is less rampant in the cultural capitals of Moscow and St. Petersburg. There, gay clubs, beaches and bookstores thrive because of a highly concentAnti-homophobia demonstration in Russia. Marco Fieber. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.rated LGBTQ+ community. On the other hand, in Siberia, the presence of gay life diminishes as the threat of hate-fueled violence increases. Gay men have been lured to online dates in remote locations only to find a violent gang of homophobes when they arrive. Police have been known to abuse queer people as well. Yevgeniy once drove to nearby Angarsk after a supposedly gay boy had been brutalized by two strangers. When he arrived, the police had arrested the boy to accost him about his sexuality, letting the attackers go.

This environment demands a different approach to LGBTQ+ activism than in Russia’s European part. There, activists like Nikolay Alexeyev vociferously demand their rights. Alexeyev organized the first Moscow Pride parade in 2006, which then mayor of Moscow Yuri Luzhkov deemed “satanic.” The participants in the small parade faced arrests from the police and attacks from Neo-Nazis, but the subsequent, yearly demonstrations made Alexeyev the public face of the gay rights movement. He frequently brings his combative style to TV debate shows. On such a show, he grew so frustrated with a fancifully-hatted woman decrying “homosexual extremism” that he called her a “hag in a hat” and left.

A protest placard mocking Putin. Marco Fieber. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Alexeyev often makes life difficult for gay activists in far-flung areas of Russia. Yevgeniy claims that the Russians he interacts with on a daily basis aren’t ready for Pride festivals, and that his pugnacity alienates those they need to win over. Irkutsk Oblast is home to 2.5 million people, but only forty LGBT activists, Yevgeniy estimates. His work with Time to Act doesn’t even pay. For money, he works at a local bakery.

A long road lies ahead for Yevgeniy and his fellow activists. LGBTQ+ folks remain political untouchables across the Russian political spectrum. Even Alexei Navalny, Putin’s most powerful foe, does not touch the issue of gay rights. Amnesty International revoked his status as prisoner of conscience mainly because of his unapologetic xenophobia, but also because of his comments about the LGBTQ+ community. In a recent interview, Navalny repeatedly used a Russian slur to describe gay people.

In the Soviet era, gay folks, if discovered, were sent to gulags—brutal work camps that relied on the frigid tundra to stop prisoners from escaping. Queer artistic luminaries such as filmmaker Sergey Paradjanov and poet Anna Barkova were enslaved there, leaving a legacy of queer survival. Their spirit invigorates LGBTQ+ activism in Russia; it is sorely needed. Although gulags now sit empty, queer Russians too often find their only safe haven in the closet.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

A Trippy Trip: The Psychedelic Salt Mines of Russia

The salt mines of Russia are as dizzying in person as they appear in photos. Although a visit is not for the faint of heart, the mines stand as yet another testament to the gentle, artistic hand of nature.

Red swirls cover the walls of this Russian salt mine. Mikhail Mishainik. Daily Mail.

Along the eastern edge of Russia’s Ural Mountains lies the city of Yekaterinburg, an industrial giant currently experiencing an explosion in population and construction. Although the city itself overflows with its buzzing nightlife scene and hectic economic sector, a nearby site also attracts curious eyes and aspiring photographers. 650 feet below Yekaterinburg lies a peculiar system of salt mines often known as the “psychedelic salt mines.”

These mines earned the name “psychedelic” for the hypnotizing pattern that covers the entirety of the caves. Any visitor would be easily mesmerized by the sight; the walls display a magnificent swirling pattern that mimics sound waves or animated gusts of wind. How the caves came to be such a fascinating art show is equally interesting, as the rich, almost electric swirls of blue, yellow, red and orange are entirely natural. They exist due to large deposits of the mineral carnallite, which is commonly used in fertilizer. The mineral showcases its vibrant range in the caves, but can also be found in a colorless state. Unlike most popular caves, the psychedelic salt mines are not narrow passages requiring extreme flexibility to squeeze through; the winding channels stretch for many miles and are truly spacious.

Cave walls underneath Yekaterinburg. Mikhail Mishainik. Daily Mail.

The caves date back 280 million years to the Permian period, and are a result of the Perm Sea having dried up. These rich salt deposits were largely forgotten for many years until around the second millennium B.C., when Russia began salt mining.

Additionally, only recently have photos of the cave even been shown to the public. Although the attractive site seems ideal for family-friendly adventures and novice photographers, the caves are closed off to the public. Only a small section of the caves are still in use, and the other parts require a special government permit to access.

However, a photographer named Mikhail Mishainik is credited with the awe-inspiring photos we now see. Along with some friends, Mishainik spent many hours exploring the caves, being sure to capture the magnificence of their artwork along the way. Mishainik stayed overnight in the pitch-black caves and chronicled his uncomfortable yet exciting experience. Due to the mineral deposits, the air inside is salty and dry, creating a constant feeling of unquenchable, perpetual thirst. Mishainik also claims that the lingering sense of instability in the caves is part of the excitement, since the caves face the threat of gas leaks and landslides.

It is uncertain whether any more than a select few will ever lay their eyes on the rainbow swirls of these caves, but one thing is sure: if such magnificence lies hidden under this one city, there are limitless other gems waiting to be uncovered by unsuspecting travelers.

RELATED CONTENT:

VIDEO: RUSSIA: Kamchatka Volcanoes

7 Stunning Caves Worth Exploring

VIDEO: A Diamond Mine in the Rough

Ella Nguyen

Ella is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.

Women at the End of the Land

FIELD JOURNAL #1

I arrive in late autumn. The tundra seems vast and empty to the horizon. Only two dark pyramid-shaped “chums” (traditional Nenets’ tents) with tendrils of smoke rising from their tips stand out against the crisp blue sky.

No reindeer yet. Rather, I can hear the barking of dogs as they run between a chain of sledges. I look around, searching for the reindeer, but only the tundra greets me. As far as the eye can see, only brown earth and azure sky.

As I walk to explore the land, I discover the difficulty in moving before the land freezes and snow falls. It is very difficult to walk and I tire quickly, feeling much pain in my knees. The uneven ground makes it necessary to plan each step and the numerous water pods create muddy soft soil. We cannot travel any great distance in the sledge under these conditions as the reindeer are at risk of injury .

— October 21, 2016, Yamal Peninsula, Northwest Siberia

The Northern Lights arch high above the chum of the Khudi family, while sparks fly from the stove inside. Each year, the family must migrate to winter grazing lands with their reindeer, but without snow passage across the tundra is difficult to impossible.

FIELD JOURNAL #2

It’s my first morning in the chum, and I wake to unfamiliar surroundings. Whispering in a foreign language. I sneak a look from my warm sleeping bag and through the darkness I see the fur head cover of Lena. Above me dangles boots and clothing made of fur and reindeer hide. For a moment I’m overwhelmed with the knowledge that I will be spending the next fifty days living in these tight quarters with this family. I wonder how they must feel sharing their home with a stranger. These feelings are completely balanced with the knowledge that kindness, generosity, open hearts and gratitude are part of a universal language. No matter where we are born, we share these common human expressions. And so, the first moment we make eye contact, we are all sharing smiles.

— October 22, 2016, Yamal Peninsula, Northwest Siberia

Once the ground has frozen and a deep enough layer of snow has settled, Lena and her family can pack up their home and belongings onto their traditional wooden sledges, pulled by reindeer, and embark on their annual migration to find winter grazing lands for their herd.

“YAMAL” OR AT THE END OF THE WORLD

Living in small chums constructed of reindeer hides and log poles, and often separated from their nearest neighbor by a day’s snowmobile drive, the nomadic Nenets herders trek every winter along ancient migration routes across the vast Siberian tundra along the Yamal Peninsula. In their native language, “Yamal” means “the end of the world.” Herding hundreds of reindeer and surviving daily in extreme arctic conditions, many Nenets families maintain their traditions — adapting them, where useful and necessary, in response to the increasing pressures of their changing world.

Khudi family portrait. Left to right: Lena, her 4-year-old daughter, Christina, under blankets in the baby cradle, her newborn son, Phillip, and her husband, Leonya. Not pictured, the couple’s 9-year-old son, Ephim, who is currently attending the village boarding school.

Unfortunately, this environment is currently under strain from outside forces. The Yamal Peninsula contains one of the largest natural gas reserves on the planet. Following a succession of atypically hot summers, it appears that Siberia’s permafrost is melting at an unprecedented rate, posing a significant threat those who call this region home. As the permafrost melts, it is releasing millions of tons of carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, damaging the Nenets’ traditional pastureland, threatening their reindeer herds and leading to increasingly unpredictable weather patterns. Widespread pipeline construction also disturbs their campsites, and passages across the land causing the loss of the Nenets’ traditional migratory patterns.

It is common for Nenets families to raise an orphan reindeer inside their chums, hand feeding the youngster until they are mature. Even after these reindeer return to the herd, the Nenets often maintain an intimate relationship with these particular individuals.

I came to the Siberian tundra from mid-October through mid-December 2016 as a photographer and ethnographer to study and document the Nenets’ way of life. Specifically, I wanted to explore how a traditional Nenets family prepares for their winter migration, the ways that they have adjusted to modern life, and how their culture and values have shifted in the light of development and climate change.

At the heart of my expedition was the opportunity to document a Nenets woman’s ninth month of pregnancy and share her journey to birth.

NOVEMBER 10TH.

We’ve been waiting for snow for weeks. We need to migrate to the winter camp where the reindeer herd will have enough food and Lena’s family can settle in with their new infant. However, snow has been slow to arrive and the baby’s birth is impending. As with all births, planning on this timescale can be tricky. Lena and her husband, Leonya are hoping to minimize the duration that Lena is away from her critical domestic responsibilities as preparation for winter migration requires both men and women to be wholly engaged with activities for both daily sustenance and long-term survival.

The plan has been for Lena to contact the Helicopter Department at Salekhard hospital as she nears her delivery date. The helicopter will transport her and her daughter Christina to this hospital where she will stay for approximately two to three weeks to deliver her child and recover before returning by train, snowmobile, and sledge back to the chum, a journey that takes approximately twenty hours. Lena has once already sent the helicopter away when it arrived a month earlier to take her into the village.

Each day Lena can remain out on the tundra with her family is critical to their survival. Yet, time is running out and there is still much to be done.

Lena’s domestic responsibilities are crucial to support her family given the extreme environment. She must coordinate with the hospital helicopter service for pick up in advance of going into labor, but not too early as her ongoing presence out on the tundra is essential.

Regardless of her physical condition, Lena continues to accomplish her wide range of daily responsibilities. She is the first one to wake and the last to go to sleep. Every morning, she makes a fire, unties the dogs from their place in the chum and lets them outside. Then she sets about preparing the tea table for breakfast. After they eat, Leonya, who tells us to call him Leo, leaves to go work with their reindeer herd — the family has several hundred reindeer that are grazing many kilometers away.

Every day, Leo leaves the chum early in the morning, returns briefly for lunch, and goes back out with the herd until evening.

On Leo’s departure, Lena goes outside in the frigid temperatures to cut more firewood, a task I offer to help with, but am amazed to discover I am almost incapable to perform. Apparently, there is a technique to swinging an axe, one that even though I’m physically fit requires a practised swing over the shoulder. My attempts are near disaster as my upward swing threatens to take out everything and everyone behind me.

Even in her ninth month of pregnancy, Lena lifts the axe with a deftness I can only wish for — I am forced to leave the chopping to her.

Lena locates, gathers, and chops all the wood that is needed to keep the fire burning at all times inside the chum. With winter temperatures that can reach -50°c, these tasks are essential for the family’s survival and well-being.

I can help by bringing the firewood inside, as Lena’s morning is filled with other responsibilities: beating the fresh fallen snow off the chum walls, splitting the chimney to empty the black particles left behind by the smoke, gathering items from the various sledges, and collecting water from the reservoirs. These have become iced over, requiring Lena to break them open with a pole to reach the water beneath. Once inside again, she prepares food for, then feeds, the dogs, and then cooks a meal for lunch.

Lena fills her free time with making clothes for her family. Each item of a Nenets’ winter costume is taken from a specific part of the reindeer. For example, the hides used for boots are cultivated in middle of the winter to ensure the thickest fur.

All the while, Lena is taking care of Christina, who is remarkably content occupying herself with found objects and the ice pods, her favourite. I grow to love this small child, and spend many hours playing with her.

Four-year-old Christina is at home with the cold. Her favorite part of the tundra playground? The multiple pools of water as they begin to freeze and become ice pods.

NOVEMBER 18TH

The ice layer has thickened during the past three days and Leonya says that he would like to start the migration in a couple of days, this will be the sixth time since my arrival that the family has attempted to migrate. To prepare, the several hundred reindeer must be herded into a tight circle for traveling. This requires Lena’s assistance to handle the dogs on leashes as they circle the herd, dogs barking. While the men lasso the herd, Lena helps by circling approximately a thousand reindeer, managing a large dog tethered to a long leash for several hours to keep the herd together until the lassoing is finished.

Although the family’s dogs must work hard, and make an important contribution to the Nenets’ ability to survive out on the tundra with their reindeer, they also provide affection and an occasional playmate for four-year-old Christina.

The dog barks and in his enthusiasm runs around, tugging the leash and making the work even more difficult, as Lena has to continue pulling him back and controlling the pace of the walk. It is extremely tiring work which requires constant attention as well as physical strength and agility. I try it and am amazed at how difficult it was to keep the dog away from the herd. After only a couple of rounds I am utterly exhausted. Towards the end the dog is pulling so hard that Lena slips and falls on her stomach. We reach her almost immediately, extremely worried. But she gets up quickly, smiles, and assures us she is okay. She continues until the job is complete.

Days away from giving birth, Lena works to herd the reindeer into a tight circle in preparation for migration.

As well as documenting Lena’s final weeks of pregnancy and birth, taking part in the Nenets’ traditional winter migration with their reindeer is one of the primary reasons for my visit during this time of year. But, because of the unseasonable weather conditions, the tundra has not been ready for us to make the trip. We’ve been waiting for over thirty days for enough consistent freeze and snowfall to make the migration route possible.

Earlier this month, I rode the sledge for five hours to reach the nearest village, in order to recharge my camera batteries.

The pain from the cold to my feet and my fingers was almost unbearable, and if not for the medical expertise of the local Nenets woman minding the supply shelter, I would likely have suffered from severe frostbite.

My plan for our migration is now to wrap my feet and hands with several layers of fur and felt blankets to make sure the wind is not penetrating my skin. I have realised this means that I will not be able to photograph during the actual migration, as Leoyna has insisted I must be fastened to the sledge with ropes for safety, so I will have no workable use of my limbs.

Handmade wooden sledges have been used by generations of Nenets as an efficient way to transport their belongings across the vast expanses of frozen tundra. Reindeer pull the often heavily-laden sledges, while the dogs guide alongside.

I am still able to capture the activities as the family prepares for migration: lassoing the reindeer, unpacking and repacking sledges, preparing the caravan and disassembling the chum. Yet, while I was so eager to take part in the actual winter migration, I am disappointed to realise I will not be able to take photographs while actually travelling on this journey. I must take extreme care to protect my camera gear. Although it will be secured on the sledge and wrapped in fur, the strong winds and significant temperature drops put the equipment at risk.

I will need to carry all ten batteries on my body the entire time in order to keep them warm or else they will drain rapidly due to the cold.

As the seasons change, Nenets families change their chum coverings from light summer skin to thick fur hide. Passed down through generations, the winter cover consists of four layers of reindeer skin, stitched by hand over a whole year, from more then one hundred reindeer.

Lena tells us that she will contact the helicopter to pick her up a day earlier than planned, as she feels her delivery is impending. Our plan is to migrate now and then when we are set up in the new camp, the helicopter will come retrieve her to make the transfer to the hospital. The railways have been placed along the ancient migration routes, disrupting the migration patterns, but also providing an unintended benefit. There is cell reception within two kilometers of the tracks, and Nenets families now typically set up camp within short distances so they can access cellular service in an emergency.

Among the belongings the Khudi family carry from camp to camp is this small box containing special items such as religious cards, family treasures, and photographs

NOVEMBER 2OTH.

At two am on the day we are supposed to begin the migration, Leo wakes me from a sound sleep. Lena is experiencing pain in her lower abdomen and believes they are contractions. Leo has called the village from his mobile phone and asked them to contact the helicopter in Salekhard.

However, the helicopter cannot fly during the night so they have set arrival for daybreak, which at this time of year does not occur until almost 10am. They have advised us to send for the nurse at the closest trading station, but reception is here is faulty and now we can no longer get through, even when we attempt to communicate with my sat phone. Leo ends up walking a moonlit, but bitter cold two kilometers to the train tracks where he can get more reliable cell service. On his way back, he alerts his relative, Igor, whose family’s chum is nearby. Igor takes off in his snowmobile to pick up the nurse approximately two hours away.

By three-thirty, Lena clearly needs medical support and Leo is worried.

He wants to contact the helicopter department again and try to convince them to make the night trip, with the logic that the full moon will provide the necessary light and that the chum is close enough to the railways, so it will be an easy landmark for the pilots to follow until the flashing of the snowmobile lights that Leo will use to guide the helicopter to the chum.

In the commotion, Christina wakes up and asks what is happening. She is not aware that her mother is pregnant and her parents have decided not to tell her beforehand because they believe she will be jealous. In just a few hours she will be taken with her mother on a helicopter to the village hospital and temporarily placed in a child welfare center. She is aware of none of this and I worry for her, even as there is no other solution. Without her mother to care for her, Christina cannot stay on the tundra.

The elements are no match for traditional Nenets’ winter costume. Dressed properly, Christina can play outside for hours.

We are all now awake and waiting. Not one to panic in crisis, Lena begins to carefully pack her belongings. In addition to her personal necessities, she takes sewing tools, small boots, and scraps of fur so she can work while she is in the hospital. When she is ready, Lena turns to me and Zalphira, my translator and asks us what we are going to do now, after she is gone.

At the heart of the Nenets’ chum is the stove. Lena must constantly ensure there is adequate fuel to keep her family warm, and uses the stove for all essential household needs, such as cooking and cleaning.

Then it hits me, the depth to which we simply cannot survive here without Lena. Even the most basic acts for surviving in this landscape, such as making sure there is always a fire to keep us warm means not just placing fuel in the stove, but, with no other fuel, determining where and how to find wood when it is buried in the ice and snow. When supplies are exhausted in the near vicinity, how do we travel to the outlying areas to search for and collect more? This is only one basic element of the chores Lena tends to daily. Preparing food and cooking in this environment are skills that take time to learn and Leonya will not be able help as he is wholly tending to the herd.

Each member of a traditional Nenets family has specific responsibilities that together are essential to their collective survival on the tundra. While, Leo tends to the reindeer herd out on the tundra, Lena cares for their four year old daughter, Christina.

Thankfully, we have an answer to Lena’s question. Our hope is to travel by helicopter and accompany her to Salekhard. Barring this opportunity, we will hire a truckle and drive the twelve hours to the village by sledge and snowmobile, where I will document Lena’s birth experience in any way I can.

There is nothing left to do now but wait and for the next two hours we all try to get some rest. I wake again to the sound of a fire starting. Though experiencing contractions, Lena remains committed to her responsibility as a mother, a wife, and also a host. While we are all still resting and anticipating, she gets up and places more wood in the stove to warm water for tea. It’s seven a.m and still dark outside. We wonder who will arrive first — the nurse or the helicopter.

We don’t have to wait long for our answer, as after our first sips of tea, the increasing buzz of a snowmobile sounds off in the distance. A few moments later, after traveling for several hours on a box sledge, Galina, the nurse, arrives. She wastes no time and Galina’s first communication with Lena is to firmly ask, “Why didn’t you go to the hospital a month ago?” Galina then checks her blood pressure and asks when Lena last had an ultrasound to check the baby’s position. After a full check-up, Galina and Leo set off for the railways to attempt another communication with the helicopter department.

In the early hours of the morning, on the day the family had finally planned to begin their migration, Lena experiences her first contractions. By 7:30 am Galina, a nurse from the closest trading station, two hours away, arrives to assist Lena.

Finally, the sun has risen, it’s ten am and the helicopter’s hovering presence overhead is a thunderous contrast to the daily stillness we have grown accustomed to. The pilot circles us twice then prepares to land.

The entire process happens surprisingly fast. Upon landing, two officials and nurses jump out and approach Lena and begin to load her and Christina into the helicopter. Christina pulls back, frightened, but her father walks the family to the opening and sees them off. I was not permitted to accompany them as I had hoped. Just like that they are gone.

At dawn, the helicopter arrives to collect Lena, and a frightened, resistant, Christina.

The tundra is eerily silent when the helicopter departs. Without Lena and Christina, the entire landscape feels abruptly stark and lonely.

When we enter the chum it feels empty not only of bodies, but also of energy, and spirit. Outside, the sledges are packed and ready to travel for migration. But, without Lena we cannot move. It will be at least two weeks before she returns with her newborn and Christina. Everything must be unpacked and migration will be postponed. This could put the herd in jeopardy, as quality-grazing areas are difficult to come by, with the most sought after spots taken by the earliest migrating Nenets with the largest herds.

In order to migrate, the eight hundred reindeer that make up the herd must be corralled into a tight circle.

Although their migration has now been temporarily suspended, Lena has successfully reduced the time she will be away from her family. When she returns with Christina and their newborn son, the family will move their herd to a winter camp.

Zalphira and I recognize that we cannot possibly stay and survive without Lena. Yet, I wonder how Lyonya will manage without his partner, how will he possibly prepare food and keep the chum from freezing when he is required to be out with the reindeer herd for long hours?

One of many lessons I’ve learned during my time here is that the unexpected is every day. You can’t control a sudden snowstorm, a sick reindeer, or rain in November, but the way you prepare for possibilities and how you adapt to change are the keys to survival.

This was the day we prepared to migrate, and instead it is the day Lena and Leonya’s child will be born. As the sun finds its place briefly overhead, I understand that the journey I will take now, while not planned, is something I’m prepared for. We will travel eight hours by sledge and then snowmobile back to the village where Lena is about to give birth. There I will wait and gather stories. The reindeer stand like stoics, painstakingly herded and ready to go. Their puffs of cloud breath visible against the crisp blue sky.

WOMEN AT THE END OF THE LAND: THE BOOK

This story is part of a longer narrative that will be published in the forthcoming photography book, Woman at the End of the Land. A close collaboration with writer Kim Frank, this book will share a rich and detailed glimpse into Lena’s birth journey, as well as explore my experiences documenting the Nenets’ daily lives at a time of great change in their history, when rapid climate change and industrial development pose a significant threat to their unique way of life.

Learn more about the book / Order photographic prints

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

ALEGRA ALLY

Alegra is an ethnographer and award-winning explorer and photographer, whose work has focused worldwide on indigenous cultures. She is the founder of the @wildbornproject and member of the Explorers Club F&H committee.

Love and Rubbish: Documentary on Child Poverty In Russia

If you live in poverty, can you afford to dream? An estimated five million people are homeless in Russia; one million of them are children. This WHY POVERTY film takes a look at the lives of a group of children living on a rubbish dump outside of Moscow, showing the hardships they face and the dreams they hold on to.