Dubai’s emerging food scene is attracting some of the best chefs from all over the world. One of those chefs is Reif Othman, who has worked in a variety of kitchens, from fine dining restaurants to innovative pop-ups. He’s taking Chef Ching He Huang on a tour of this eclectic foodie paradise to show why professionals are choosing a life in Dubai.

An Ancient Practice with Peru’s Last Medicine Men

Rosendo is a curandero, a healer who specializes in natural, plant-based medicines. He has been honing his trade in the mountains of the high Amazon, and at 86, he is one of the last remaining curanderos in the region. Now, he is passing the baton to his son Mauro in an effort to rescue this fading art. Our friends at Jungles in Paris bring us this story from San Martin, Peru.

The Great Mosque of Aleppo, Syria, was destroyed in December 2016. Fathi Nezam /Tasnim News Agency, CC BY-NC-SA

Destroying Cultural Heritage Is an Attack on Humanity’s Past and Present – It Must Be Prevented

Since Sun Tzu wrote The Art of War in China in the sixth century BC, military writers have argued that to destroy the cultural heritage of your enemy is bad military practice. Many international agreements since have banned the destruction of cultural heritage in war. That is why there was a horrified reaction to President Trump’s recent threat to Iran’s cultural heritage following the assassination of General Soleimani.

Read MoreEPA-EFE/CPL Tristan Kennedy/First Joint Public Affairs Unit handout

Bushfires: Can Ecosystems Recover From Such Dramatic Losses of Biodiversity?

The sheer scale and intensity of the Australian bushfire crisis have led to apocalyptic scenes making the front pages of newspapers the world over. An estimated 10 million hectares(100,000 sq km) of land have burned since 1 July 2019. At least 28 people have died. And over a billion animals are estimated to have been killed to date. Of course, the actual toll will be much higher if major animal groups, such as insects, are included in these estimates.

The impacts of climate change – in particular, the consequences of the increasing frequency of extreme weather events on all life should be abundantly clear. People finally seem to be taking this seriously, but there is an undercurrent of opinion about the “naturalness” of wildfires. Some are still questioning the role of climate change in driving the Australian bushfires.

It is true that wildfires naturally occur in many parts of the world, and benefit plants and animals in ecosystems that have been uniquely shaped by fire over evolutionary time. And people have been using fire to manage ecosystems for thousands of years. We could learn a thing or two from Aboriginal people and the techniques they have traditionally used to prevent bushfires.

But make no mistake, the scientific evidence shows that human-caused climate change is a key driver of the rapid and unprecedented increases in wildfire activity. What is particularly worrying is the extent to which this is eroding the resilience of ecosystems across wide regions. Yes, it is plausible to expect most plants and animals that have adapted to fire will recover. But the ecological costs of huge, repetitive, high-severity wildfires on ecosystems could be colossal.

A dead Koala is seen after bushfires swept through Kangaroo Island, Australia, 07 January 2020. EPA-EFE/David Marius

Out of control

And it’s unclear how much the natural world can tolerate such dramatic disturbance. Wildfires are increasing in severity around the world. The Australian bushfires are larger than some of the deadliest recorded. Incidences are also increasing in ecosystems where wildfires are uncommon, such as the UK uplands. Not to mention the widespread deliberate burning of areas of high conservation value for agriculture, as has been recently reported in large parts of the Brazilian Amazon for beef production and in Indonesia for palm oil.

Unsurprisingly, given the shocking numbers of animals that must have perished as a result of these wildfires, many are questioning whether burned ecosystems can recover from such dramatic losses of biodiversity. In Australia, for example, some estimate that the fires could drive more than 700 insect species to extinction.

The world’s biodiversity is already severely struggling – we are in the midst of what scientists describe as the sixth mass extinction. A recent report has highlighted that about a quarter of assessed species are threatened with extinction. Australia already has the highest rate of mammal loss for any region in the world, signalling the fragility of existing ecosystems that might struggle to function in a warming, fire prone world.

Carcasses of cows killed in a bushfire in a field in Coolagolite, New South Wales, Australia, 1 January 2020. EPA-EFE/Sean Davey

Fears for familiar and charismatic animals affected by the bushfires, such as koala, have been expressed by conservationists. The outlook for already critically endangered species, such as the regent honeyeater and western ground parrot, meanwhile, is uncertain. But to establish the true ecological costs of wildfires it is important to consider biodiversity in terms of networks, not particular species or numbers of animals.

All species are embedded in complex networks of interactions where they are directly and indirectly dependent on each other. A food web is a good example of such networks. The simultaneous loss of such large numbers of plants and animals could have cascading impacts on the ways species interact – and hence the ability of ecosystems to bounce back and properly function following high-severity wildfires.

A fragile system

And so it’s key that we consider biodiversity loss due to wildfires in terms of entire networks of interacting organisms, including humans, rather than simply one or two charismatic animals. I have studied and recently published research about the loss of plants and animals due to wildfires in Portugal, using new methods in ecology that can examine the resilience of ecosystems to species extinctions. My team found that networks of interacting plants and animals at burned sites became fragile and more prone to species extinctions.

Our study looked at the impacts of a large wildfire in 2012 on one of the many ecological interactions that keep ecosystems healthy – insect pollination. We examined the responses of moths, which are important but often overlooked pollinators, to wildfire by comparing those we caught in burned and neighbouring unburned areas.

The hummingbird hawk moth. Research in Portugal is revealing the importance of moths as pollinators.Claudio306/Shutterstock.com

By collecting, counting and identifying the thousands of pollen grains they were carrying, we were able to decipher the plant-insect network of interacting species. In this way, it was possible to examine not only the responses of the plants and animals to wildfire, but crucially the impacts on pollination processes.

We then used these networks to model the resilience of the ecosystem more generally. We found that burned areas had significantly more abundant flowers (due to a flush of plants whose seeds and roots survived in the soil) but less abundant and species‐rich moths. The total amount of pollen being transported by the moths in burned areas was just 20% of that at unburned areas.

Our analysis revealed important differences in the way these species interacted as a result of the wildfire. Although the study was only a snapshot in time, we were able to show that plant-insect communities at burned sites were less able to resist the effects of any further disturbances without suffering species extinctions.

And so as people start rebuilding their homes, livelihoods and communities in Australia following the devastating bushfires, it is crucial that governments and land managers around the world take sensible decisions that will build resilience into ecosystems. To do this, ecological interaction networks need to be considered, rather than specific species. Cutting-edge network approaches that examine the complex ways in which entire communities of species interact can and should help with this.

Over 45 years ago, the American evolutionary ecologist and conservationist Dan Janzen wrote: “There is a much more insidious kind of extinction: the extinction of ecological interactions.” We should all be concerned not just about the loss of animals, but about the unravelling of species interactions within ecosystems on which we all depend for our survival.

Darren Evans is a Reader in Ecology and Conservation, Newcastle University

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Gender Matters in Coastal Livelihood Programs in Indonesia

Significant investments have been made in improving the well-being of Indonesian coastal communities in recent decades. However, most of these programs have not tackled gender inequalities.

Projects based on comprehensive understanding of gender norms in coastal communities will contribute to improved community wellbeing. www.shutterstock.com

Our team studied 20 coastal livelihood programs implemented across the Indonesian archipelago from 1998 to 2017. Our aim was to see how gender issues were considered in project design and implementation.

The Indonesian government, international governments, international development and lending agencies and non-government conservation organisations funded these projects.

Most projects included women in activities to enhance or introduce new livelihoods. However, 40% of the projects were gender-blind with respect to the design and impact of their activities. This means that activities may have further entrenched processes that disadvantage women by limiting their ability to pursue their own livelihood goals.

Only two projects (10%) used an approach that sought to challenge entrenched gender norms and truly empower women.

We recommend future projects be developed with a comprehensive understanding of gender norms within coastal communities. Participatory approaches that address and challenge these norms should be implemented. This will more effectively contribute to improvements in community well-being.

What we found

Our study, which assessed livelihood programs from various regions throughout Indonesia – including Bali, Sulawesi and West Papua – found 95% of programs had directly or indirectly included women. They did so through activities such as providing training and equipment to support alternative sources of income – e.g. making fish or mangrove-based food products.

Only three of the 20 projects provided gender awareness training for staff members and community facilitators. Only one provided similar training at the community level. In addition, two projects included a gender quota for community facilitators (30-50% female).

However, we found most projects applied either a “gender reinforcing” approach – reinforcing the existing gender norms and relations that underlie social and economic inequalities between men and women – or a “gender accommodating” approach – recognising these norms and relations but making no attempt to challenge them.

For example, many projects included separate “women’s activities”, such as handicrafts manufacture, or sought to increase household income by engaging women in income-generating enterprise groups. However, there was little consideration of how women would balance these activities with traditional caring and household roles, or of other ways women contributed to the household economy.

What we can do

Based on our findings, we recommend a “gender transformative” approach. Firstly, this approach involves mainstreaming gender issues across entire project cycles. Secondly, it involves working with coastal communities to identify and, where appropriate, challenge existing gender norms and social relations.

A core component of these projects is gender analysis. This is a process that identifies:

men’s and women’s activities within the home and community

differences in men’s and women’s access to, control over and use of livelihood resources

differences in participation in processes that govern management of natural resources

the gender norms and relations governing these differences

their impact on men’s and women’s livelihood opportunities.

For example, the Coastal Field School program included participatory activities that documented men’s and women’s daily activities. This activity highlighted the time women spent on caring and household duties and unpaid supportive contributions to “men’s activities”.

When undertaken in a participatory manner, this analysis helps communities to identify local, and broader structural, barriers to gender equality. They can then identify options and potential actions for overcoming these barriers. This creates a more equitable social and economic environment.

Summary of the characteristics of approaches to gender in development programs (based on Lawless et al. 2017), with examples of typical project activities drawn from our. study. Stacey et al (2019).

This process must be sensitively facilitated because it may confront traditional power hierarchies within communities. It also takes time, which must be factored into project cycles.

The use of gender-transformative approaches can improve the well-being of coastal communities by identifying and reducing barriers to equitable participation in social and economic life. This increases the ability of men and women to pursue enhanced or alternative livelihood opportunities.

Finally, recognising women’s contributions, building women’s confidence and giving women voice to participate in local community planning processes creates greater opportunities for issues of concern to women to be included in the development agenda.

Natasha Stacey is a Associate Professor, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, College of Engineering, IT and Environment, Charles Darwin University

Emily Gibson is a PhD Candidate, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Be skeptical of organic claims on cleaning products and other nonfood goods. Pinkasevich/Shutterstock

Buyers Should Beware of Organic Labels on Nonfood Products

Product labels offer valuable information to consumers, but manufacturers can misuse them to increase profits. This is particularly true for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s organic label.

Two recent decisions by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, which protects consumers from unfair and deceptive business practices, signal that the agency is paying more attention to misuse of the word “organic” on nonfood items, such as clothing and personal care products. In my research on food and environmental policy, I have found that federal authority in this area is less clear than it is for food products. In my view, the FTC’s interest is long overdue.

The rules are mostly for foods

The USDA organic seal. USDA

Unlike other marketing claims such as “healthy” or “natural,” “organic” is defined and regulated by the federal government. Organic food products undergo a rigorous certification process to comply with the National Organic Program, or NOP, which is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Only agricultural products that contain at least 95% certified organic ingredients meet these standards and can display the USDA organic seal or use the phrase “made with organic products.” USDA organic certification is considered the gold standard among food labels, and has significant cachet in the marketplace. In 2018 the U.S. organic food market was valued at US$49.9 billion and accounted for almost 6% of nationwide food sales.

All sorts of nonfood products also make organic claims, including textiles, household cleaners, personal care products and services such as house cleaning and dry cleaning. Nonfood products are a much smaller market, but their sales jumped by 10.6% to $4.6 billion in 2018. While they may appear to promote healthy lifestyles, the word “organic” is less meaningful when used on nonfood products and more subject to abuse.

Organic nonfood products with agricultural ingredients

While the NOP regulates organic claims for agricultural food products, its authority over nonfood products is limited. Textiles, for example, are made from agricultural products like cotton, wool or flax. Textiles made from agricultural ingredients that are “produced in full compliance with the NOP regulations” may be labeled as NOP certified organic.

USDA regulates organic claims for goods made with plant materials such as cotton. Scoobyfoo/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Personal care products can also be made from agricultural ingredients, such as flower or fruit extracts and oils. USDA allows personal care products that contain agricultural ingredients and meet the USDA/NOP organic standards to be certified organic. As a result, you can find mosquito repellent, shampoo and face cream bearing the USDA certified organic seal.

Consumer confusion

Beyond these limited categories, products with non-agricultural ingredients do not generally fall within the NOP program, and the USDA does not regulate them. For example, the agency has no authority over cosmetics that do not contain agricultural ingredients or meet NOP organic standards. Cosmetics are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, which has expressed little interest in policing organic claims.

The Federal Trade Commission can investigate and sue companies making false, misleading or deceptive organic claims, but until recently it has been reluctant to do so, partly to avoid duplicating the USDA’s efforts. This began to change in 2015 when the two agencies conducted a study on public understanding of organic claims for nonfood products. They found that consumers were confused about whether these claims meant the same thing as claims on food products, and did not understand that USDA had limited authority in this area.

When the agencies co-hosted a roundtable in 2016 on this issue and solicited public input, they received hundreds of comments from individuals, trade associations and other interested groups. One individual wrote:

“I am deeply concerned about the flagrant misuse of the term "organic” in the personal care products industry. The term “organic” should mean the same thing whether applied to personal care products or to food. I am also very troubled that companies that deliberately mislabel their products seem to go unpunished.“

The nonprofit Cornucopia Institute, which acts as an organic industry watchdog, submitted results of a survey it conducted about the word organic. One question asked consumers whether a shampoo labeled organic was certified by the USDA. Approximately 27% of respondents said yes, 55% said no and the rest were unsure.

The Institute urged the FTC to "harmonize label regulation with the [NOP organic] standards in a simple way: Prevent the term ‘organic’ from being used on products and services that generally fall outside the scope of the USDA’s National Organic Program.”

In my view, this is unlikely to happen. But one useful step would be for the FTC to include information about organic claims in its Green Guide, which is designed to help marketers avoid making misleading or deceptive environmental claims.

Recent violations

In 2017 the FTC stepped in for the first time to investigate deceptive organic claims on baby mattresses. According to a consent order filed with the agency, Moonlight Slumber, LLC made unsubstantiated representations on its mattresses, including that the mattresses were “organic.” In fact, the company’s products were made of a majority of non-organic materials, mainly polyurethane, a plastic produced almost entirely from petroleum-based raw materials.

In October 2019 the FTC fined another company, Truly Organic, $1.76 million for falsely advertising its body washes, lotions, baby, hair care, bath and cleaning products as “certified organic,” “USDA certified organic,” and “Truly Organic.” Despite having some ingredients that could be organically sourced, Truly Organic products either contained ingredients that were not approved by NOP or contained ingredients that were not organically sourced.

The FTC charged Truly Organic with altering documents to make it appear that the company’s products were USDA-certified organic.

Nonetheless, the market for natural and organic personal care products continues to grow, as evidenced by the popularity of celebrity brands like Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop and Jessica Alba’s Honest Company. Demand for this category of goods is projected to reach $17.6 billion by 2021.

Consumers want clean, chemical-free and organic products, but they don’t always get them. Many personal care companies have been cited for misleading claims. As examples, Goop and the Honest Company have settled lawsuits that accused them respectively of making misleading health claims and false advertising.

Instead of relying on consumers to bring these claims to court, I believe regulators should be more engaged, particularly the FTC. Without effective oversight, unscrupulous retailers have an incentive to continue cashing in on the organic seal.

Sarah J. Morath is a Clinical Associate Professor of Law and Director of Lawyering Skills and Strategies, University of Houston

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Ugandan opposition politician Bobi Wine takes a selfie with Zimbabwe’s opposition leader Nelson Chamisa Aaron Ufumeli/EPA-EFE

UGANDA: Politics and Fashion - The Rise of the Red Beret

Bobi Wine has come a long way in two years. The self-styled “Ghetto President” of Uganda used to be a music star, playing politically charged reggae beats to packed houses. In 2017, the politics took over.

Donning a red beret, he formed the People Power movement, running a successful grassroots campaign to be elected as a parliamentary representative. Now, he’s challenging Yoweri Museveni for the presidency in 2021.

In two years, Wine’s red beret has become synonymous with a fiery spirit of Ugandan resistance, long since thought to be extinguished after 33 years of ironclad rule by Museveni.

In the beret, Wine cannily put the “brand” in “firebrand” across his multiple social media platforms. In response, the regime is turning to unconventional suppression tactics. On September 18, 2019, a government gazette listed the red beret as official military attire, effectively banning it from public life.

Symbolism

Perhaps fittingly for a time of stark global inequality, red headgear is currently marking global populist movements of all political persuasions. The French Revolution brought us the “bonnet rouge” and red is historically synonymous with leftist politics. But red baseball caps famously heralded the 2016 US election of Trump in a rustbelt resurgence.

South Africa has its own version of working-class red: the Economic Freedom Fighters. The opposition party’s trademark red beret forms part of a trio of headgear including the wrap and hard hat. Within weeks of the party debuting their look, sales skyrocketed. Similarly, Make America Great Again hat sales have soared to one million in 2019.

A beret may not make a worker’s revolutionary, but it certainly makes a statement. Its history is equal part bohemian artist and militant revolutionary; it’s been worn by everyone from Rembrandt to Robert Mugabe, the Beatniks to the Black Panther movement.

Fittingly, Wine styles himself as both artist and activist, his career as a musician merging seamlessly into his political manifesto. “When we sing ‘Tulivimba mu Uganda empya’ (We shall move with swag in a new Uganda), we summarise what our struggle is about - DIGNITY,” proclaimed Wine in a tweet.

An EFF supporter carries a painting of party leader Julius Malema during an election rally. STR/EPA-EFE

Social media

Indeed, Wine’s social media presence is key to his success, spreading message and image interchangeably. Using his prolific Twitter, Facebook and Instagram presence, he is relentlessly visual: nearly every update is accompanied by an image of beret-clad supporters. His near daily updates centre less on local rallies than on his increasingly high profile, Western travel and media coverage. It’s a canny move in a country where 78% of the population is under 35.

Bobi Wine and his red beret made it onto the Next 100 list. Time magazine

The Ugandan regime is nothing if not wise to this: on July 1, 2018, the government instigated what was dubbed a “social media tax”, charging Ugandans 200 shillings (roughly five US cents) a day to use a bouquet of 60 internet applications, including WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. While the price may not seem prohibitive, it still presents a big structural barrier in a country where 41.7% of people were living on less than $2 a day in 2018.

“Social media use is definitely a luxury item,” announced Museveni, ironically on his personal blog. He continued:

Internet use can sometimes be used for education purposes and research. This should not be taxed. However, using internet to access social media for chatting, recreation, malice, subversion, inciting murder, is definitely a luxury.

The social media tax has added a new twist to Museveni’s suppression tactics. While virtual private networks allow more savvy Ugandan users a way around the problem, others take the hit and pay the price.

Familiar tactics

Wine’s tactical use of music and fashion follows Museveni’s own playbook. The Ugandan president released his own popular song in November 2010.

Museveni wears trademark wide-brimmed hat. Mike Hutchins/EPA-EFE

Unlike Wine’s populist reggae, Museveni’s “U Want Another Rap” is mostly sung in Runyankore, a language predominantly spoken in rural areas of the country. Its heavy-handed lyrics emphasise individual resilience, like “harvesters … gave me millet, that I gave to a hen, which gave me an egg, that I gave to children, who gave me a monkey, that I gave to the king, who gave me a cow, that I used to marry my wife.”

In line with this folksy approach, Museveni famously favours a wide-brimmed conservative sunhat with leather string. Like Wine’s, the hat is a feature of most leadership portraits. The contrast couldn’t be starker: an old man with a broad-brimmed gardening hat and his young, hip rival in revolutionary red branded beret.

Practicality

Against the backdrop of a Ugandan dictatorship that controls media narrative, then, viable opposition needs a boost. Wine’s choice of symbol fits well. Berets are convenient: cheap to produce and impossible to ignore. The splash of red next to the face makes its way into every photograph. Unlike a T-shirt, headgear is easily stashed or discarded during confrontation without immediately signalling a clothing item has been removed.

Dr Rosie Findlay, digital fashion media specialist and author of Personal Style Blogs: Appearances that Fascinate, says the fact that the beret is being deployed on social media should not be overlooked.

The colour pops on the small screen and is immediately recognisable, a literal fashion statement in how its symbolism immediately marks Wine’s image with his politics.

In the face of the banning of the red beret by Museveni, Wine seems unfazed:

He thinks it is about the beret - it’s not. This is a symbolisation of the desire for change. People Power is more than a red beret, we are bigger than our symbol.

With 18 months before the next Ugandan election and two hats in the ring, let us see if revolutionary spectacle can translate into substantial governance.

US President Donald Trump holds his famous red cap, a symbol of the rising right. Michael Reynolds/EPA-EFE

Carla Lever is a Research Fellow at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Truckistan

Pakistani truck owners have taken moving art to a new level with their mobile murals on their vehicles. Check out this vibrant video about Pakistan truck art and culture.

Read MoreA Decade In Fashion: From Church Hats to Sneaker Heads

What we wear says a lot about us. Fashion is more than just trends, it’s culture and self-expression. From Brooklyn’s green queen, to Mexico’s pachucos, we’ve got all the looks. Strut your stuff as we celebrate a decade in fashion.

This Man Runs a Micronation of 32 People

Welcome to the Republic of Molossia: Population 32. Although not officially recognized by the United States, Molossia is a self-declared nation in the middle of the Nevada desert. This micronation has its own post office, bank and space program. Its president (and benevolent dictator), Kevin Baugh, has found the perfect way to combine politics with a sense of humor.

In Tanzania, a Garden That Feeds Bellies and Brains

For O’Brien School for the Maasai teacher Saphi Yohana, growing a garden isn’t just a nice thing to do—it’s a way keep kids in the classroom. Most of the school’s students come from the Maasai tribe, once an exclusively nomadic people who traditionally eat milk, meat, blood and fat. As increased droughts have made this diet less and less attainable, malnourishment has spread. By providing two veggie-based meals a day, the O’Brien School is now greeting energized, happy students each morning and sending them home each afternoon to spread a passion for produce.

The development of an industry in edible insects such as these mopane caterpillars has been slow. Shutterstock

Why We’re Involved in a Project in Africa to Promote Edible Insects

There is a wealth of indigenous knowledge about capturing and eating insects in sub-Saharan Africa. But the development of edible insects as a food industry has been very slow, despite its many potential benefits.

Sustainability is one. Insects have a small carbon and water footprint. Studies show that insect farming emits less carbon and methane gas than large livestock like cattle and pigs. Much less water is needed to produce the same amount of protein. Insects use feed more efficiently than other sources of animal protein. Farming them could be a new source of jobs and income.

There should be more awareness and promotion of insects as food for humans and as feed for animals, especially at the policy, legislative and business level. In most African nations, edible insects are still viewed as an insignificant source of food and even, in some instances, as food for the poor. There are very few success stories of large-scale insect farming and industrial use in Africa.

We have been involved in a project to promote the integrated use of insects as food in urban areas in Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Our project works on the edible insect value chain and discovered that the seasonal supply of insects and poor hygiene standards made the market unstable and unattractive to consumers. Traders sold insects in an informal setting and had little interaction with farmers.

We carried out training among farmers, traders, municipalities and others with an interest in this emerging industry. The training included how to handle and process insects after they were harvested, food safety along the value chain and farming crickets (Acheta domesticus and Gryllus bumaculatus).

The trainees have learnt how to rear and sell insects better and have become more aware of what a sustainable value chain should look like. For example, market facilities have to be clean and there must be a steady supply of insects. The training also created awareness of the need to farm insects rather than catching them in the wild. Catching insects can reduce insect populations dramatically when consumption increases. And there are no food safety standards for wild insects.

Together with the urban council in the town of Chinhoyi in Zimbabwe we built a model market structure where traders are selling their insects. Traders are selling some of the most popular edible insects; wild harvested mopane worms (Gonimbrasia belina), termites (Macrotermes natalensis) and wild harvested crickets. Farmers are still building stocks of farmed crickets, but the plan is to sell farmed crickets in the near future. It is still too early to see the impact but one notable improvement is hygiene. The market has also helped women traders, who are the main group selling insects there. They have become more organised about their business.

We hope this will lead to an increase in consumer willingness to buy edible insects, and demonstrate best practice to other regions of Zimbabwe and beyond. Through our project, we have also helped insect traders and farmers to form industry associations.

Why insects are valuable

Insects are highly nutritious and contain protein, fat and energy in proportions similar to grains, vegetables and seeds. They are rich in macro minerals like calcium, sodium and magnesium and micro minerals like zinc, manganese, iron and copper, all of which should be part of a healthy diet. In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, these minerals come from fruits and vegetables, most of which are farmed seasonally. Edible insects could supply these minerals during seasons where there is less fruit and vegetable production.

They contain essential amino acids such as threonine, cysteine, valine, methionine and isoleucine. The recommended daily minimum intake of amino acids can be consumed by eating just 100 grams of the edible stink bug (Encosternum delegorguei), for example.

Earlier this year, parts of eastern and southern Africa were ravaged by Cyclone Idai. The cyclone destroyed crops and livestock, causing severe food shortages. We believe that in disaster-struck areas, edible insects can build resilience by being a food resource in recovery programmes and an alternative to traditional smallholder farming. There is an excellent example of that in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where orphanages have started insect farms to grow their own protein. The farms have helped decrease hunger and improve health among the orphans.

Read more: Economic chaos is causing a food security and humanitarian crisis in Zimbabwe

What needs to happen?

We were involved in setting up an international conference in Zimbabwe to discuss ways to foster the edible insects industry.

Research is required so that policy makers and those involved in the sector – farmers, processes, marketers and consumers – can make evidence-based decisions. This must happen across disciplines. Researchers should work with farmers and people in business to foster skills, innovation and enterprise. For example, they could develop business cases and scenarios.

Policy makers must understand that the sector is unique. Edible insects have not been categorised under any agricultural sub-sector such as crop or animal farming. On the African continent, they have not previously been farmed and treated as a commodity. That is why it would be helpful to establish and coordinate platforms such as meetings, workshops, exhibitions, magazines and websites.

Policy should also allow innovation and investment to happen at national, regional and international levels. Industry participants will need access to markets and credit.

Farmers, food and feed processors, traders and marketers must seize opportunities to invest and enter niche markets. They can also contribute to policy development and share knowledge about traditional ways of producing and eating insects.

There is momentum generated by several research and business initiatives that have been ignited in sub-Saharan Africa. And there is growing enthusiasm for using edible insects as alternative sources of protein and to build resilience against climatic shocks. It’s an essential step towards improving food security in the region.

Robert Musundire is a Associate Professor of Entomology in the Department of Crop Science and Post-Harvest Technology, Chinhoyi University of Technology

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

University students have different motivations for their social media use. Wikimedia Commons

How New Media Can Be Used to Spark Interest in Elections Among Young Ghanaians

There has been growing evidence around the world that young people are increasingly becoming apathetic about taking part in events such as elections, according to Ceron in a study conducted in 2015. Given that university students are also increasingly using social media, scholars have started to look at how it can be used to invigorate their diminishing interest in governance as well as in elections.

We conducted research on how students in Ghana used new media. The aim was to understand the motivations and political information needs that influenced them to use new media technologies for elections.

We found that young people were drawn to use new media technologies to have conversations on elections. Posts going viral gave them a sense of relevance and empowerment. Another reason was that it gave them the opportunity to engage in the comfort of their private spaces – offline.

The findings should enable more strategic targeting of university students by political actors and institutions. This could be in terms of turn out efforts, political messaging, communication as well as political campaigning. This has already been done successfully in a number of countries.

How it’s been done elsewhere

New media technologies have been used in a myriad of ways to mobilise people to vote in various countries. For example, in Italy in 2014, Sweden in 2010 and in the 2010 British elections.

Astute use of technologies was also evident in Barack Obama’s campaigns for the US presidency in 2008 and 2012.

In Africa, social media was used during the mass protests of 2011 in Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco. In all three cases, people uploaded photographs of the protests which then went viral. This reinforced global appreciation of the need for democratic change in the countries.

Social media has also been used to monitor elections and disseminate results. For instance in Nigeria, young Nigerians embarked on the “Enough is Enough” campaign on election vigilance to hold politically elected leaders accountable.

In Ghana, some civil society groups launched the “the Voter Decides” campaign in 2012. This sought to track the process of voting, monitor collation of results and ensure that the right results were announced.

But the deployment of various new media technologies by political actors for elections and other civil engagements hasn’t necessarily translated into reversing the dwindling interest in politics. This is clear from research by communication scholars like Christian Vaccari.

It raises the question: what motivates the young new media user to deploy the technologies from an informational and communications perspective?

Why Ghanaian Students use new media technologies

In our research on Ghanaian students, our main findings were that:

Students are drawn to deploying new media technologies for the currency and breadth of information they can access.

They are both consumers and producers of media content.

They are able to navigate their way around the gatekeeping or filtration process conducted by editors.

The opportunity to go viral or become virtual celebrities in seconds when they click the “enter” or “send” button is an experience they relish.

The virtual space is a safe haven for many.

They spend a great deal of time on social media. This is attested to when a student asserts: “my world is on the mobile phone.”

The potency of social media

Our findings reinforce the view that social media is a viable resource that can be relied on for voter mobilisation, campaigning and voting. Students suggest that political candidates must find ways to woo Ghanaian students into conversations before election fever catches on. If the candidates delay, their efforts will be perceived by the youth as self-serving.

Practically, many young people want to be part of the process of constructing political narratives offline rather than on campaign platforms. They want to be in their safe haven – online and anonymous – where they can’t be reproached for their youthful exuberance.

These kinds of conversations have the potential of reducing apathy and getting young people involved in the political process.

Political actors and candidates should seriously look at how media technologies can be used for effective reciprocal political communication with university students. If they understand what motivates and influences students to use new media technologies for conversations on the elections, political actors are much more likely to be able to count on the involvement of young people in conversations on the elections and participation in the electoral process.

Adwoa Sikayena Amankwah is a Senior Lecturer of Communication Studies, University of Professional Studies Accra

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Bringing Humanity to Asylum Seekers' Journey

Sra. Sánchez’s Albergue del Jesus el Buen Pastor has offered medical care and support to asylum seekers who have fallen ill or become injured during the dangerous trek to the U.S. Sánchez aids hundreds of individuals each month, and for her service has been recognized by a number of human rights organizations.

Read MoreDuring Floods, Floating Schools Bring the Classroom to Students

Each year, over one-fifth of Bangladesh suffers from flooding. And when water overtakes already struggling roads, much of life is put on hold—including kids’ education. But if children can’t travel to the classroom, architect and entrepreneur Mohammed Rezwan thought, why not have it travel to them? Welcome aboard the Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha floating school—a network of boats that’s both school bus and schoolhouse for students ages six to ten in Northern Bangladesh.

Putting Kenya’s Slums on the Map

These days, the Internet makes it possible to travel much of the world with a simple click of a mouse. But not every place where life gets lived is cartographically represented. This leaves entire communities, particularly slums and other “informal settlements,” invisible from state actors who could implement vital infrastructure like electricity and clean water. Using their feet, GPS technology and a lot of dedication, Primož Kovačič, Isaac Motisiamosa and their teams are collaborating to put Mathare, Kenya’s second largest slum, and its people on the map.

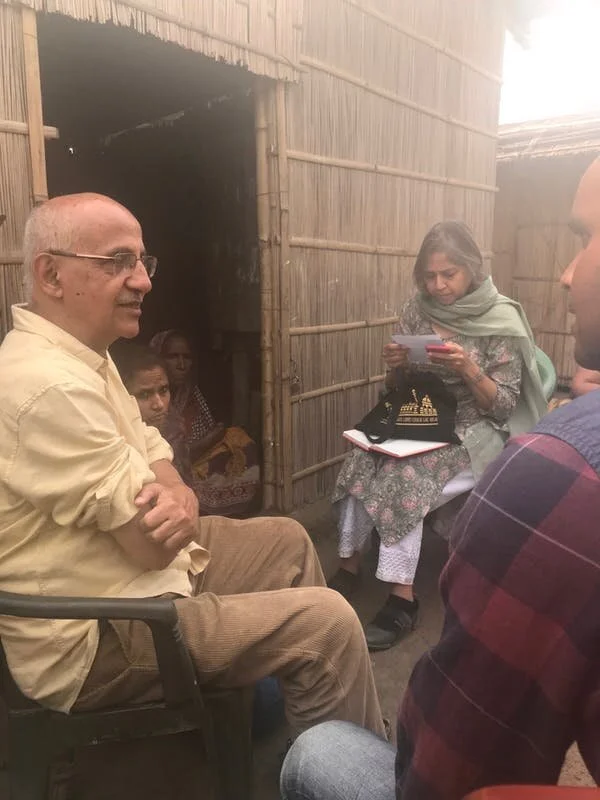

Activists and local volunteers meet and console Assamese villagers who might have lost their Indian citizenship. Anuradha Sen Mookerjee, Author provided

In India’s Assam, a Solidarity Network Has Emerged to Help Those at Risk of Becoming Stateless

The state of Assam in India is currently burning with violent protests against a new citizenship law passed by both houses of the Indian parliament in early December.

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) will ease the Indian citizenship process for undocumented migrants in India who come from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh – but only for those who are not Muslim, undermining the promise of equality by the Indian Constitution. The international community criticised the new law, with the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights calling it “fundamentally discriminatory”.

Since its parliamentary approval on December 12, the law has triggered massive protests across India including in the capital Delhi.

Concerns in Assam

Assam is directly affected by the new law. It significantly undermines the National Register of Citizens (NRC), a listing process that has been underway in Assam since 2015 through which residents have to prove their claim to citizenship based on documentary evidence. The NRC is designed to update a first list conducted as an all-India exercise in 1951 to combat illegal immigration flows, primarily from neighbouring Bangladesh.

More than 1.9 million people in Assam – many of whom are Muslim – have failed to make it onto the NRC’s final list which was published on August 31. They now face the risk of statelessness. But at the same time, the large numbers of Hindus who were excluded in the NRC system can now become Indian citizens under the CAA.

The way the CAA is written makes way for Indian citizenship of all non-Muslims who lived in certain areas of Assam, such as the Brahmaputra Valley, before or on December 31 2014, even if they don’t have documentary evidence, and while rendering Muslims stateless. It contradicts the cut-off date for inclusion used by the NRC, which was midnight on March 24 1971.

For the protesters on Assam’s streets, the CAA gives legal rights to the large numbers of undocumented Bengali-speaking Hindus who have migrated from Bangladesh since 1971 and also those currently excluded by the NRC.

Their fear is twofold. First, indigenous Assamese feel that with the inclusion of the Bengali speaking Hindus by the CAA, the composite number of Bengali speaking people (both Hindus and Muslims) will outnumber the Assamese speaking people in the state. Census data shows that the Assamese-speaking people in the state declined from 58% of the population in 1991 to 48% in 2011. Second, the Muslims both excluded by NRC and those who have migrated later, risk becoming stateless.

A journey to the Pampara Char

I’ve seen up close the damage the NRC process has had on communities in Assam. In mid-November, I visited the state with the Indian peace activist Harsh Mandar and several others as part of an initiative called Karwan e Mohabbat, a human caravan of peace, justice, solidarity and consciousness as part of my research on citizenship in the Indian borderlands.

We visited the homes of people who have been excluded from the NRC, particularly from the Muslim community in Lower Assam districts. We listened and learned about their experiences of trauma, suffering and hopelessness with the filing of their documents and how they are coping with their exclusion.

Among the people we met in the Barpeta district of Lower Assam were inhabitants of the Chars, low-lying temporary sand islands formed by silt deposition and erosion. These sand bars, which emerge and submerge in the river beds of Assam’s Brahmaputra river, are uniquely vulnerable to disasters such as floods and cyclones.

Pampara Char, one of the silt islands on the Brahmaputra river, Barpeta district, Lower Assam. Google Maps

Wild grass, thatched huts and distressed residents

The Pampara Char is a barren wasteland, with wild grass growing all over the place and houses that looked like temporary huts. The only brick building, which was freshly painted in white and blue, was the primary school. It stood distinct from the other houses and seemed sparingly used. The people, toughened by poverty and harsh ecology, were left distraught by their experience of the NRC and gathered around Harsh Mandar and other social activists to share their suffering and tales of horror about the registration process. Many had to go through repeated verification across different drafts of the list.

View of the fields in one of the village visited in Pampara Char. Anuradha S.Mookerjee, Author provided

I observed deep anxiety among the people we met, such as the aggrieved 54-year-old Khaled Ali. Illiterate and landless, Ali is a river fisherman who sometimes also works as a daily wage labourer. Like many others he received a notice in early August that he and his 18 other family members needed to submit more documents or they would be excluded from the final NRC list. Their names had been included in two previous versions.

A reverification hearing was scheduled for the next day in the distant town of Golaghat, which is 460km away from the Pamapara Char. Overnight, Ali raised a loan of 30,000 Indian rupees (US$424 or €383) to travel to Golaghat, with all his family members and two witnesses in a hired bus. After an 18-hour trip, they reached Golaghat and were received by local civil society activists who arranged for them to camp at a community centre and also helped them to submit their documents.

After their reverification hearing, Ali and his family members found themselves excluded in the final NRC list. While they have 120 days to appeal against their exclusion, his wife lamented that they lack the money to produce more documents from paralegals to support their cases before the appeal deadline on December 29. Meanwhile, a distraught Ali told us that he still has a loan of 14,000 rupees (US$198 or €178) to repay.

Complex documentation process

Harsh Mander and other social activists listening to the plea of the Char villagers. Anuradha S.Mookerjee, Author provided

For marginal and illiterate residents of the Chars such as Ali, the NRC and the process of proving citizenship has become a very stressful and expensive burden. As we found out during our home visits, a new parallel economy of document production has flourished. Paralegals charged anywhere between 500 to 1,000 Rupees for each document, a very large sum for these poor people.

The highly complex documentation process, which includes requirement for family trees and residency documents dating back to before March 24 1971, is also to blame for the exclusion of large numbers of people from the final NRC register. The process is extremely insensitive to the difficulties of the large mass of illiterate and poverty-stricken populations who are finding it very difficult to make sense of how to navigate registration on their own.

Processes of verification and reverification have been implemented in a way that firmly establish a hierarchical relation between the state and its citizens, with the complete domination by bureaucrats and public office holders over the rights of the citizens and residents.

‘Citizen-making’ humanitarians of Assam

Many of the marginalised populations in Lower Assam, such as Ali and his family, have needed constant support to be able to file their documents and fight their cases.

Local activists are playing a significant role in helping people deal with the burden of proving their citizenship, understanding the terminology and filling in the application forms and claims. They are also offering guidance about attending case hearings, support in procuring documents for submission from paralegals and also offering psycho-social counselling.

In Barpeta, volunteer Shahjahan Ali Ahmed receives an award from social activist Uma Shankari in recognition of his work helping people left out of the NRC. Anuradha S.Mookerjee, Author provided

Volunteers and human rights groups of Lower Assam have also connected with civil society actors in Upper Assam to help residents commute from Lower to Upper Assam for hearings and verification, and on some occasion even raise money, creating a solidarity network.

Such a humanitarian network is crucial at a time when marginalised people feel threatened with the changing legal regime which seeks to redefine the basis of Indian citizenship. These networks of solidarity in India’s north-eastern borderlands attempt to draw out the real Indian body politic, reinforcing the plural fabric of the Indian constitution.

Anuradha Sen Mookerjee is a Research fellow, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID)

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Reinventing Electronic Music With Dubai’s Cellist DJ

When classical cellist Aaron Kim was diagnosed with critical hearing loss, he had two choices: to keep creating music or to stop altogether. Kim chose the former and has since discovered a passion for electronic music. Combining his classical training with new sounds, Kim produces unconventional electronic beats for the emerging underground music scene in Dubai. The freedom to create music on his own terms, without any rules or structures, has helped Kim break and overcome barriers that once held him back.

How Curious George Escaped Nazi Germany

Curious George is the mischievous child that still lives inside us all, a swinging catastrophe with an envious joie de vivre. But everyone’s favorite chimp almost didn’t make it to the page. The story goes way back to 1940 as Nazi forces prepared to invade France. German-Jewish artists H.A. and Margret Rey fled Paris by bicycle, carrying the original manuscript that would later become “Curious George.” From there George traveled the globe, trekking down to Lisbon, sailing across the pond to Rio de Janeiro, finally making his home in New York. The rest, of course, is history, as our primate protagonist climbed his way into our hearts and onto the world’s stage.

Battle Rap’s First LGBTQ League

Bronx-born Sara Kana is a child of hip-hop and the mother of Prism Battle League. First launched in 2016, Prism is a platform for emcees in the LGBTQ community to compete in a battle of words, wise and wit. Painfully familiar with homophobia in and beyond hip-hop, Sara hopes for Prism to be a safe, inclusive space that allows battle rap talent to flourish—so much so, she funds it herself.