After enduring decades of damming, Indigenous teens recently completed the first full descent of the Klamath River, regaining the waterway and their history.

Read MoreZapatista Radio: Indigenous Broadcasts Resist Erasure in Mexico

In Chiapas, Mexico, Zapatista-run community radio stations preserve Mayan languages, report local issues and bypass state-controlled narratives.

Read MoreHow AI Can Preserve Endangered Languages

As minority native languages worldwide disappear at a rapid rate, Indigenous scientists look to new AI language learning models and community participation as a way of preserving their cultures.

Read MoreReclaiming the Chagos Islands: Unraveling the Colonial Legacy of Mauritius

The significant return of the Chagos Islands, after centuries of British control, serves as a poignant reminder of the legacy of colonialism and the ongoing hurdles that must be overcome.

Read MoreWhat Happened to Australia’s ‘Stolen Generation’?

Zoe Lodge

A look into the history and consequence of removal practices against indigenous Australian youth, the “Stolen Generation.”

Indigenous Australian children. Mark Roy. CC BY-SA 2.0.

From the early 20th century until as late as the 1970s, Australia carried out a government-sanctioned campaign that forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families in a bid to assimilate them into white society. While much global attention has focused on the legacy of boarding schools for Indigenous children in North America, similar practices were inflicted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples under British colonial rule, often with the encouragement of the Roman Catholic Church and other Christian institutions. These efforts left generational scars, contributing to the systemic inequality and social fragmentation that persist into the modern day.

This dark chapter in Australian history is commonly referred to as the “Stolen Generation.” According to a report conducted by the U.S. Department of the Interior, which investigated comparable initiatives across the globe, roughly one in three Indigenous children in Australia were forcibly taken from their homes between 1910 and 1970. These children were placed in church- and state-run institutions or sent to live with white families that exemplified Western values, where they were stripped of their language, culture and identity. The underlying goal, both ideological and colonial, was to “civilize” these children by erasing their cultural roots and integrating them into a white-dominated society.

These practices were grounded in a racist belief system that deemed white Australian culture, rooted in Western European culture, inherently superior. Authorities at the time regarded the removal of Indigenous children as a moral duty and a practical solution to what was referred to as “the Aboriginal problem.” In reality, the result was a trauma that has rippled through generations. Children taken from their families frequently endured physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and, in many cases, sexual assault. They were often treated as cheap labor and denied access to adequate education and healthcare.

Although Australia never formally established a network of Indigenous boarding schools akin to those in the U.S. and Canada, the assimilationist mission was no less destructive. Despite making up only about 6% of Australia’s youth population, Indigenous children account for almost 50% of those in out-of-home care, which includes placement in foster care, group homes and with kinship carers. This gaping disparity emphasizes the lasting effects of these programs, leaving First Nations people to deal with dislocation, cultural loss and intergenerational trauma.

In recent years, the Australian government has taken steps to acknowledge and atone for these policies. A national apology was issued in 2008, followed by reparations exceeding $375 million for surviving members of the Stolen Generation. Additionally, individual states have contributed over $200 million in compensation funds for those affected. However, many argue that financial reparations, while important, cannot undo the profound harm caused by decades of systemic cultural erasure and displacement.

Australia’s history with its Indigenous populations is not unique. As the DOI report highlights, these tactics of domination and forced assimilation are not isolated but part of a broader colonial pattern seen across Canada, the United States and New Zealand. These initiatives, driven by the dual forces of governmental policies and religious institutions, sought to erase Indigenous culture in favor of Eurocentric ideals. From the earliest boarding schools in the United States and Canada to parallel programs in Australia and New Zealand, the common thread was the colonial power’s blatant disregard for the autonomy, culture and humanity of Indigenous communities, particularly through religious messaging and values. These institutions inflicted lasting harm, not only by physically removing children from their homes and subjecting them to abuse but also by obliterating the cultural traditions and languages that sustained Indigenous identities for generations.

GET INVOLVED:

One of the primary organizations focused on bringing justice to the First Nations people of Australia is ANTAR, which offers several ways to get involved, raise awareness and contribute to justice for the Indigenous people of Australia. Locals can volunteer with the organizations, and citizens worldwide can contribute to fundraising efforts or participate in global education and awareness campaigns. Other organizations with similar missions include Pay the Rent, IWGIA and the Aboriginal Legal Service.

Zoe Lodge

Zoe is a student at the University of California, Berkeley, where she is studying English and Politics, Philosophy, & Law. She combines her passion for writing with her love for travel, interest in combatting climate change, and concern for social justice issues.

The First Documentary? Or an Utter Falsehood?: "Nanook of the North"

Cemented as a piece of cultural iconography of the Inuit Peoples, "Nanook of the North" exemplifies how art and exploitation can coexist.

Read MoreOppenheimer’s Critical Omission: The Relocation of Hispanic and Indigenous Populations

Intricate but incomplete, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer disregards the true history of Hispanic and Indigenous populations in New Mexico.

Trinity Nuclear Test. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. CC0.

A picturesque aquamarine sky hangs lazily above a dusty, deserted New Mexico landscape. Through a tangle of brush, a lanky Robert Oppenheimer, played by Irish actor Cillian Murphy, emerges on horseback. His eyes feast on the remote plains and he declares that besides a local boys’ school and “Indian” burial grounds, Los Alamos will be the perfect site to construct the world’s first atomic weapons.

These momentous decisions and moral quandaries are explored in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. Grossing $450 million in its first fourteen days at the box office, the 1940s period piece has cemented itself as a somewhat unlikely cultural icon. Gone are the days of Nolan’s slightly fantastical films — notably Inception (2010) and Interstellar (2014). Recently, the Academy Award-nominated director has been dipping his toes in the realism of period pieces, beginning with Dunkirk (2017) and continuing with Oppenheimer.

Nolan’s portrayal of Oppenheimer — based on the biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin — is deliberately layered. The audience travels alongside Oppenheimer over the course of his life for three hours. On one hand, Oppenheimer’s humanity is a gut punch: viewers experience his mistress’s death, his tumultuous marriage, and his gradual realization of the death and destruction his scientific creation has wrought. On the other, viewers gaze upon the physicist with disgust: the man was, as he infamously declared himself, a destroyer of worlds.

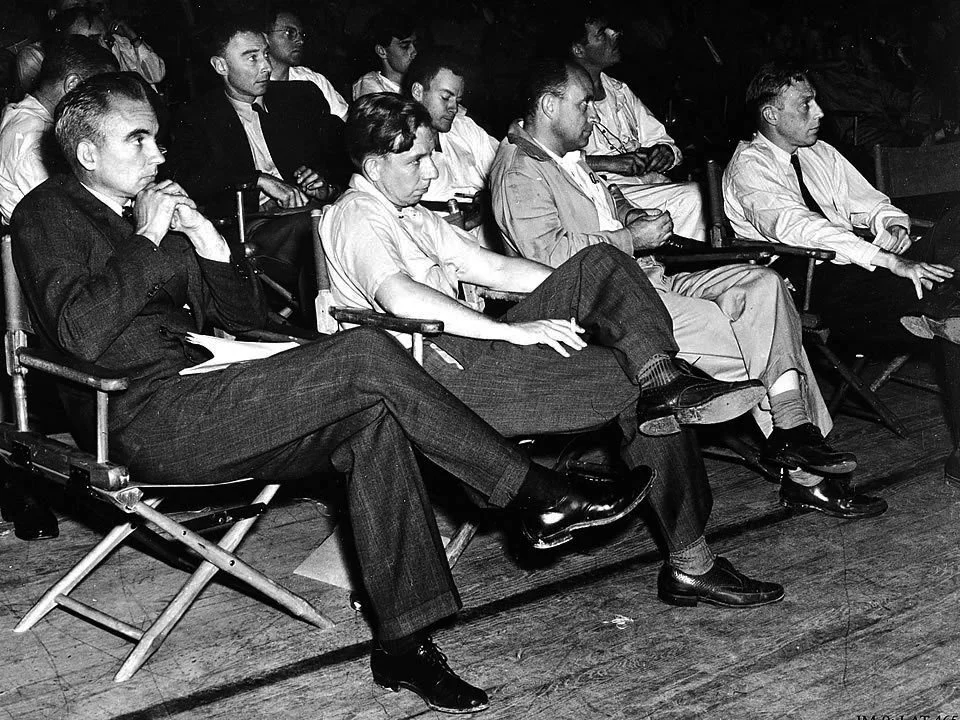

J. Robert Oppenheimer. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. CC0.

The use of the first atomic bomb by the United States to defeat Japan and win World War II is one of the signal events of the modern era, arguably helping to prevent a land invasion of Japan that could have killed millions. Despite the magnitude of this technical and geopolitical accomplishment, the legacy of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will forever cast a negative light on the United States government and the team of nuclear physicists involved in the development of the atomic bomb. While Nolan acknowledges this complex legacy, his portrayal of key elements of the Manhattan Project and the Los Alamos Laboratory obscures another historical moral quandary. The remote sandy vistas in Nolan’s cinematography smother the true story of Los Alamos and the Trinity nuclear test.

The reality, omitted from Nolan’s film, is that during the Manhattan Project the U.S. Government forcibly relocated Indigenous and Hispanic populations that resided in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Contrary to the movie’s dialogue, there were two dozen homesteaders and a ranch occupying the land that was taken by the government for the project, in addition to the school mentioned by Oppenheimer. The government seized the land and offered the owners compensation based on an appraisal of the land — an amount of compensation that the government itself thought was fit. Some homesteaders, however, objected to the compensation offered by the government, considering it far too little. Many in the Federal Government would eventually come to agree with them; in 2004, decades after the original compensation, Congress established a $10 million fund to pay back the homesteaders.

Moreover, it was difficult for the homesteaders to object in the first place due to the language barrier. Most homesteaders spoke Spanish, while government officials often only communicated in English. Some families were even held at gunpoint as they were forced to leave with no explanation, due to the project’s secrecy. Livestock and other animals on property were shot or let loose. Livelihoods were destroyed along with these animals.

Los Alamos Colloquium of Physicists. Los Alamos National Laboratory. CC0.

The element of secrecy surrounding the Manhattan Project and the Trinity nuclear test disrupted the lives of families living directly on Los Alamos land. But, for the 13,000 New Mexicans living within a fifty mile radius of the Trinity test (in Jornada del Muerto, New Mexico), the nuclear explosion truly seemed to be the end of the world. Because the mushroom cloud was visible from up to 200 miles away from the test site, and no civilians knew tests were being conducted, fear erupted in concert with the explosion.

Nolan’s film not only fails to indicate that homesteaders on Los Alamos were forcibly relocated — it also fails to mention that civilians from northern to southern New Mexico were exposed to harmful radiation from the bomb. Radioactive fallout initially contaminated water and livestock, and in turn, civilians. There were no studies or treatment conducted on individuals exposed to radiation, which could have exposed the highly classified program. Those who were in the radius or downwind of the fallout became known as “downwinders,” and began to develop autoimmune diseases, chronic illness and cancer.

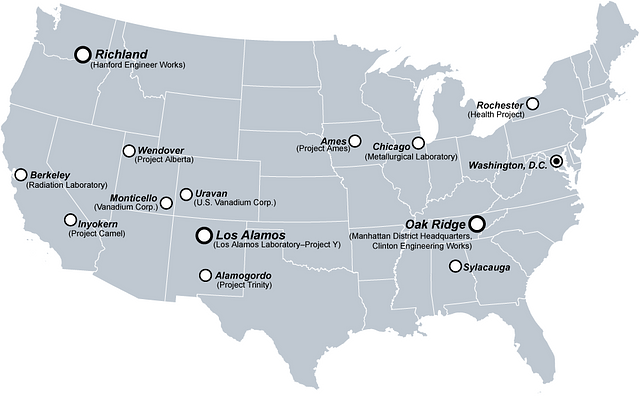

Manhattan Project U.S. Map. Wikimedia Commons. CC by 3.0.

Eventually, the Hispanic American and Indigenous populations who lived in the area returned to Los Alamos to work for the project without knowing its true nature or extent. They returned as maids or as construction workers, often handling radioactive and contaminated materials without knowledge of the harm and risk of exposure. Many became economically dependent on a laboratory that posed environmental and health risks for the greater Los Alamos population. This led to struggles with physical and mental health that have continued to the present time.

The legacy of the Manhattan Project, the Los Alamos Laboratory and the Trinity nuclear test hangs in a state of limbo. It transcends time — becoming the past, present and future for Hispanic and Indigenous populations in New Mexico. Nolan’s failure to acknowledge these populations’ displacement and unwitting contamination silences their narratives and obscures this unique patrimony. J. Robert Oppenheimer’s depiction as a thumbtack in sandy nothingness is historically inaccurate — Nolan’s cinematic depiction of desolation glosses over a more complex reality. Los Alamos was, and is, living and breathing.

Carina Cole

Carina Cole is a Media Studies student with a Correlate in Creative Writing at Vassar College. She is an avid journalist and occasional flash fiction writer. Her passion for writing overlaps with environmentalism, feminism, social justice, and a desire to travel beyond the United States. When she’s not writing, you can find her meticulously curating playlists or picking up a paintbrush.

10 Indigenous American Historical Sites to Visit

Ten million people lived in what is now the United States before Europeans arrived. These Indigenous Americans lived in complex cultures and completed amazing architectural feats that persevere to this day.

By the time European explorers arrived in the Americas, the Western Hemisphere was already home to more than 50 million people. Ten million of these people lived in what is now the United States. These Indigenous Americans developed intricate communities, religions and lifestyles, and made a lasting impact on American history and culture. Incredible sites built by Indigenous people can be found throughout the U.S. today, including cliff dwellings, multistory stone houses, earth lodges and effigies, and other stunning ruins. The history of Indigenous people is often overlooked or swept under the rug in favor of European colonists when looking at the larger context of American history, but preserved sites teach visitors about the complex cultures that came before Western settlers. These 10 sites showcase some of the impressive architectural triumphs of Indigenous people and pass on their histories.

1. Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota

Located near Stanton, North Dakota, the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site preserves the history of the Knife River region. The Knife River region, an area in North Dakota centered around a tributary of the Missouri River, has been home to a number of people groups for around 11,000 years. Not much is known about the cultures that have inhabited the Knife River region because very few artifacts from the area remain, but early written records document the lives of the Hidatsa people. Like the Mississippian people, the Hidatsa resided in earth lodges. The Mandan and Arikara were also earth lodge residents who settled in the Knife River region, and all three groups pioneered agriculture in the area while still hunting and gathering. Villages were the center of earth lodge peoples’ lives, and the park features the remains of three large villages constructed by the Hidatsa: Awatixa Xi’e village, Hidatsa village and Awatixa village.

2. Puu Loa Petroglyphs, Hawaii

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, on Hawaii’s Big Island, protects Mauna Loa and Kilauea, two of the world’s most active volcanoes. It is also home to the Puu Loa petroglyphs, stone etchings that document the lives and culture of the Native Hawaiian people. The petroglyphs are located in a lava field that is at least 500 years old, and the site has over 23,000 different petroglyphs. There are a variety of geometric designs, as well as depictions of people and tools, such as canoe sails. A number of the petroglyphs contain cupules, or holes where a portion of the umbilical cord was placed after the birth of a child in order to ensure long life. The first known written account of the petroglyphs is attributed to missionary Rev. William Ellis in 1823, but some petroglyphs likely date to the 1600s or even earlier. In addition to being used to ensure long life, some petroglyphs were used to record the movements of travelers on the island. Visitors to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park can take a 1.4-mile round trip day hike on a boardwalk to admire the petroglyphs up close.

3. Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

Probably one of the most well-known Indigenous sites in the United States, Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado preserves almost 5,000 historical sites of the ancestral Pueblo people, including 600 cliff dwellings. The ancestral Pueblo people lived at Mesa Verde for more than 700 years, from 550 to 1300 A.D. The first people settled at Mesa Verde in 550 A.D., turning from hunting and gathering to agriculture and building small villages of pithouses, sometimes sheltered in cliff alcoves. Around 750 A.D., these people began building houses above ground and became known as the Pueblo people, meaning “village dwellers.” The houses evolved from being made of poles and mud to being skillfully constructed from stone. Then, in 1200 A.D., for reasons that are unknown, the ancestral Pueblo began to move back into cliff alcoves and developed the cliff dwellings that make Mesa Verde famous. Mesa Verde’s cliff dwellings are truly incredible examples of Indigenous architecture, ranging from one- to 150-room houses. They are also some of the best-preserved cliff dwellings in North America, and visitors can tour some of the structures, like Balcony House and Cliff Palace.

4. Effigy Mounds National Monument, Iowa

Ceremonial mounds created by Indigenous Americans can be found across the United States. Effigy Mounds National Monument preserves more than 200 distinct mounds built by people known as the Woodland Indians and gives visitors a glimpse directly into Woodland Indian culture. The mounds, found in northeastern Iowa, are unique because a large number of them are effigies in the shape of animals. Thirty-one of the mounds are bear or bird effigies. The Woodland culture consisted of hunter-gatherers who during the summer lived in large campsites along the Mississippi River, which they relied on for food and water. Archaeologists and researchers do not know precisely why the effigy mounds were built, but they guess that they may have been made for religious rituals or burial ceremonies. Guided tours are available throughout the summer at Effigy Mounds to teach visitors more about the area’s rich history, and there are also hiking trails around the site.

5. Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park, California

Just outside of Santa Barbara sits the Chumash Painted Cave, a room-sized sandstone cavern filled with colorful anthropomorphic and geometric figures. The exact age of the cave paintings is unknown, but archaeologists estimate that they date to the 1600s or earlier. The paintings are attributed to the Chumash, a name referring to several groups of Indigenous people who lived along the coast of Southern California and on the nearby Channel Islands. The Chumash groups spoke a variety of what linguists refer to as the Hokan language, and they constructed canoes from pine or redwood planks, which they used to sail up and down the California coast to hunt, gather and trade with other tribes. The Chumash lived in round homes known as “aps,” organized into villages. A number of archaeological sites displaying Chumash rock art have been discovered, and the Chumash Painted Cave is one of the most well preserved. The meaning behind the figures at the painted cave is unknown, but the art may be connected to Chumash astrology and cosmology.

6. Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico

A valley in the high desert of northwestern New Mexico houses an ancient, sprawling center of ancestral Pueblo culture. Between 850 and 1250 A.D., the area that is now Chaco Culture National Historical Park was the epicenter of a widespread expansion of Chacoan culture. The Chacoan people used unique masonry techniques to construct stone houses multiple stories high, some containing hundreds of large rooms. The buildings were intricately planned out and often constructed according to solar, lunar and cardinal directions, as well as to maintain clear lines of sight between houses. By 1050, Chaco was the economic and cultural center of the San Juan Basin, with people from all over the area gathering there to share knowledge and traditions and to participate in ceremonies. A number of the great houses have been preserved and can be seen today, along with petroglyphs made by the Chacoan people. Since 2013, Chaco has also been designated an International Dark Sky Park, meaning it is one of the best places in the country to get a view of the night sky untainted by light pollution. Visitors can look at the sky the same way the Chaco people saw it a millennium ago.

7. Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, Georgia

Minutes outside of downtown Macon, Georgia, lies Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, a site shaped by 17 millennia of habitation, dating back to prehistoric times. The nomadic Paleo-Indian people arrived at the site in around 17,000 B.C., during the last ice age. Around 9,600 B.C. the Paleo-Indian era gave way to the Archaic era. The Early Archaic people were nomadic hunters as well, but evidence suggests that by the Middle Archaic period people began to build more permanent settlements and gather food. It wasn’t until the Mississippian people, who migrated to the area in 900 A.D., that the land was permanently changed, however. The Mississippians constructed impressive villages that literally reshaped the landscape, forming elaborate earthen lodges and temples that are still visible today. The Mississippian culture declined after the 1539 arrival of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, who brought with him foreign diseases that devastated the Mississippian people. Descendants of the Mississippian people, the Muscogee Creek Nation, who lived at Ocmulgee from 1600 until their forcible removal by Andrew Jackson in 1836, considered the mounds built by their ancestors to be sacred. Today, visitors to the site can see several of the mounds constructed by the Mississippian people, as well as the location of two Civil War battles.

8. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument memorializes the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn, a fight between the 7th Regiment of the U.S. Cavalry and thousands of Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho tribe members. It lies within the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana. On June 25, 1876, the 7th Regiment, led by Lt. Gen. George Custer, attacked a village of free Lakota and Cheyenne people. The battle was part of the U.S. campaign to force Indigenous people to comply with the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which created a large reservation in South Dakota intended to house the Lakota. Many Lakota did not want to give up their nomadic lifestyle in favor of a life controlled by the U.S. government, resulting in a number of armed conflicts. The Battle of Little Bighorn proved deadly for both sides, but the Lakota and Cheyenne ultimately triumphed, defeating Custer and his troops. Though the Lakota and Cheyenne tribe members won the battle, Custer’s defeat became a rallying cry for U.S. efforts to force Indigenous people onto reservations, and stronger military forces were sent to conquer the tribes. The monument includes the battlefield itself, as well as the Custer National Cemetery and a number of hiking trails.

9. Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico

Despite its name, Aztec Ruins National Monument has no association with Mexico’s Aztec empire. These large, multistory stone buildings, located within the city limits of Aztec, New Mexico, were constructed by the ancestral Pueblo. Early Western settlers thought that the site was built by the Aztecs, so they named the area “Aztec,” and the name remained even after the true builders of the ruins were discovered. Aztec Ruins was the largest ancestral Pueblo community in the Animas River valley. The site features a number of “great houses” made of stone, including the West Ruin, which had over 400 interconnected rooms. Each great house had a “great kiva,” a large, underground circular chamber used for ceremonies. Aztec Ruins also has three above-ground kivas, each encircled by three walls forming a triangle. Aztec Ruins was likely influenced by Chacoan culture, and may have even been an outlying community of Chaco. Visitors can wander through the rooms of West Ruin on a self-guided tour, or participate in ranger-led programs.

10. Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio

The term “Hopewell culture” refers not to a specific tribe, but to a “distinctive set of artifacts, earthworks and burial practices” common in areas of southern Ohio during the Middle Woodland period, from around 1 to 400 A.D. The Hopewell Mound Group is an 130-acre earthwork complex, which contains 29 burial mounds and was once enclosed by an enormous earthen wall that spanned over 2 miles and was up to 12 feet high. Remnants of the walls are still visible, as are several of the large, uniquely shaped mounds. Hopewell Culture National Historical Park encompasses five additional sites, all with fascinating remnants of the Hopewell culture. Settlements typically consisted of a few families living close together in rectangular houses with a shared garden nearby. In addition to growing domesticated plants, people of the Hopewell culture were hunters, fishers and gatherers. Visitors to the park will discover the commonalities between each distinct site by exploring the incredible Hopewell Mounds and looking at preserved artifacts.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Exploring the Wonders of Australia’s Wild and Remote Kimberley

The Kimberley region of Western Australia boasts a spectacularly diverse landscape offering both biodiversity and impressive geological formations.

Aerial view of the Kimberley. Drumsara. CC-BY-SA 2.0.

Although Australia provides plenty of examples of nature’s extraordinary beauty, few compare to the Kimberley region. Situated in Western Australia’s northernmost corner, the Kimberley is a grandiose territory teeming with rich ecosystems. A plethora of microcommunities sprinkle across its sundry landscapes while towering hills spill into vast canyons neighboring pristine swimming holes.

The region covers over 150,000 square miles, with only about 40,000 residents inhabiting the area. Perhaps the most famous part of the Kimberley is Broome’s Cable Beach, ranked as one of the world’s most gorgeous stretches of sand and sea. The beach displays nearly 14 miles of fine sand meeting glassy waters. The beach itself has an interesting history; the name “Cable Beach” comes from the telegraph cable placed there in 1889. For adventurers more daring, Tunnel Creek National Park houses the oldest cave system in Australia. Again, the history of the stop is fascinating; Aboriginal leader Jandamarra hid in the cave system but was later caught and killed at its opening.

The swirling sky at Cable Beach in Broome. hmorandell. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

However, the history of the land tells a story drastically different than the extravagant serenity the region now boasts.

Exploration of the Kimberley by Europeans was initiated in 1879 by government surveyor Alexander Forrest, who explored much of Western Australia. Upon arrival, Forrest made note of the region’s vast landscape which made it ideal for cattle grazing. From this point on, the resources of the land quickly became tied to conflict; diggers struck gold which led to a quickly fleeting gold rush, and conflicts over cattle grazing raged between the Indigenous population and newly arrived Europeans. In the mid-20th century irrigation projects led to the rise of extensive farming, primarily that of sugar cane and rice. Oil drilling and diamond mining are now conducted in the region.

Today, the Kimberley contains residents as diverse as its wildlife; there are over 100 Aboriginal communities that share the region’s unmatched tranquility as well as its bustling economic opportunities. Due to the region’s iconic landscape, nearly 300,000 travelers visit every year, producing over $300 million annually.

Tunnel Creek National Park. Nievedee. CC BY-SA 4.0.

As with most dazzling spectacles of nature, the region boasts pristine weather that complements the untouched wilderness. The wet season extends from November to April and is characterized by heavy rain and humid, sticky air. From May to October is the dry season, which is characterized by sun-drenched days and cloudless, baby blue skies.

Raft Point. Johnny. CC BY-NC 2.0.

An exciting history and a dazzling landscape make Australia’s Kimberley region a powerfully adventurous destination. Surely any visitor will find their imagination stretched by the area’s countless wonders.

Ella Nguyen

Ella is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.

Indigenous Mexican Language isn’t Spoken– it’s Whistle

While Spanish is the official language of Mexico, its many Indigenous cultures still thrive and speak their own languages within their communities.

Read MoreIndigenous Fashion Hits the Runway

Long overlooked Indigenous artists are revolutionizing the fashion world. Balancing innovation and tradition, these designers envision a sustainable, inclusive way of creating clothes.

Indigenous women sewing. SriHarsha PVSS. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Nothing about this year’s Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto (IFWTO) went according to plan. The pandemic demanded a totally virtual fashion venue without a live audience, forcing the Indigenous communities that comprise it to rethink what a fashion week could be. Then again, reimagining the fashion industry is the forte of many Indigenous designers.

The IFWTO featured 16 designers with their own unique takes on Indigenous fashion, the clothing created by designers from a native background. It included artists from across the world who are united by a shared Indigenous heritage. Combining traditional figures and techniques with mainstream styles yielded some of the week’s most exciting work. Mobilize, for instance, fused Indigenous writing and designs with streetwear hoodies and jackets to innovate style while staying true to its roots. Audiences took well to Mobilize’s style; most of its items sold out.

Mobilize and other Indigenous brands seek to fundamentally change the fashion industry’s status quo. Jamie Okuma, a California designer of Luiseño and Shoshone-Bannock descent, emphasizes resourcefulness and respect for nature in her garments. “All of my work has tradition at its core ... So I try to utilize everything possible in my work—with my art, supplies, fabric—and not be wasteful.” Crafted with patience, detail and care, her pieces are meant to be worn again and again. “We all have those go-to pieces in our closet that we keep for years and literally wear out before we retire them,” she says. “I'm here to make the go-tos, the keepers.”

Shoes designed by Jamie Okuma. nonelvis. CC By-NC-SA 2.0.

Okuma’s approach is a welcome change to the dominant fad of “fast fashion.” These items, mass produced by large companies, are designed season by season and intended to fall out of fashion and be thrown out within a year. This approach to fashion differs starkly from that of Indigenous creators, who value durability, tradition and craftsmanship, even if it comes with a much higher sticker price. Though fast fashion allows consumers to don the latest runway fashions at an affordable price, it comes at a steep environmental cost. Products often fall apart within weeks or are thrown out having never been worn, earning the style the nickname “landfill fashion.”

A billboard for Grace Lillian Lee’s fashion. Brisbane City Council. CC BY 2.0.

Grace Lillian Lee, designer and co-founder of First Nations Fashion and Design in Australia, seeks a place for Indigeneity in the mainstream. “There’s definitely a lot that non-Indigenous people and designers can learn from Indigenous people,” she says, “especially in terms of sustainability.” Her work relies heavily on the weaving techniques of Torres Strait Islanders. More than a way to promote sustainability, Lee calls her clothing “a soft entry into reconciliation and healing our people.” Such meaningful craftsmanship doesn’t fall out of style by next season; it is passed down through generations.

Lisa Folawiyo. NDaniTV. CC BY 3.0.

Indigenous fashion is just beginning to enjoy its long overdue time in the sun. Dresses by Lisa Folawiyo, a Nigerian and West Indian designer, have been worn proudly by the likes of Solange Knowles and Lupita Nyong’o. Her intricate, flowing dresses explode with color. Boasting hand-embellished designs, Folawiyo’s dresses can take up to 240 hours to complete. Her West African designs have won the plaudits of the international fashion world and effortlessly outshine the mass-produced artifacts of fast fashion.

A dress by Lisa Folawiyo. Museum at FIT. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Indigenous people still generally lack a place at the corporate level. Sage Paul, a member of Canada’s English River First Nation who now lives in Toronto, called for the post-pandemic “new normal” to include the voices of Indigenous people in an article for The Kit. Fashion emerged from a 14th-century European aristocracy, she argues, and colonized Indigenous people to steal resources, goods and fashion trends. “The colonial systems we are operating under no longer serve our society, and the only way we will evolve is by allowing new and interconnected systems to come to the fore.” That means moving Indigenous brands into the mainstream.

The IFWTO is a good place to start. Its online market links viewers directly to designers’ websites. Live panel discussions provided a glimpse into the questions and concerns of some of Indigenous fashion’s most admired artists. Videos of models strutting the catwalk resembled music videos, showcasing the unbridled possibilities of Indigenous fashion. Most importantly, it put more Indigenous designers on the map. As of now, they show no signs of slowing down.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

The Ainu: One of Japan’s Indigenous Groups

In August 2019, the Japanese government passed a law that officially recognized the Ainu as an Indigenous people group. After nearly two centuries of legalized discrimination, the Ainu are reclaiming their identity and history, and they are just getting started.

An Ainu couple before assimilation; their features are still different from those of their Japanese counterparts. Stuart Rankin. CC BY-NC 2.0.

In July, Japan unveiled the Upopoy National Ainu Museum, the country’s first cultural center dedicated to Indigenous identity. Located on the island of Hokkaido—one of the Ainu’s ancestral lands—the Upopoy Museum showcases the history of the Ainu through performances and historical relics. What is remarkable about the museum’s opening is not its resiliency amid a pandemic, but that the structure opened at all. Much like the power dynamic between American settlers and Native American tribes, the Ainu endured a legacy of forced assimilation by the ethnic Japanese and their ruling government.

Before this, the Ainu were a hunter-gatherer tribe that inhabited the northern islands of Ezo (present-day Hokkaido), the Kuril Islands and the Russian island of Sakhalin. According to archaeological records, the Ainu called these lands home as early as the 14,500 B.C. The Ainu also had strong ties to animism, a belief that manifested itself in the relationship between the Ainu and the bears on the islands. The Ainu even created a ceremony in which bear cubs were taken, raised and then sacrificed in a ritual offering. These symbolic rites guided Ainu tradition and their balanced connection with nature.

Ainu women performing a welcome dance on Hokkaido. Vladimir Tkalcic. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

When the Meiji government annexed Hokkaido in the late 19th century, the Ainu’s pastoral way of life was interrupted. While the Ainu lived in Japan, they physically differed from their Japanese counterparts. The Ainu have a more European look with lighter skin and thick hair. Men sported full beards, and women tattooed their lips once they reached adulthood. Because of this, the Japanese derided the Ainu as backward and foreign. Around this time, Japan also became the first non-European country to have defeated Russia in battle. Flush with victory and newly acquired lands, the Japanese sought to build up a national myth of military might and cultural homogeneity. One of these initiatives included a policy of forced assimilation on the island of Hokkaido.

The Japanese government enlisted the help of American consultants who had reeducated their own North American Indigenous groups. The Ainu were forced into Japanese-speaking schools and were required to change their names. As the land was repurposed for industrial and agricultural uses, the Ainu were pushed into wage labor and became an impoverished and politically disenfranchised minority. Even after World War II, the Ainu were deprived. To participate in the scientific advancements of the mid-20th century, the Japanese government essentially emboldened researchers to rob Ainu graves and remains.

The Upopoy National Museum is housed in Hokkaido, one of the Ainu’s ancestral homelands. Marek Okon. Unsplash.

In February 2019, the Japanese government introduced a bill that would officially recognize the ethnic Ainu minority as an Indigenous people for the first time. The bill included measures that would support Ainu communities, fund scholarships and educational opportunities, and allow the Ainu to cut down trees in nationally owned forests for use in traditional practices.

While many lauded the proposal, some felt that the bill missed a crucial element: an apology. In an interview with CNN, musician Oki Kano shared that he was only 20 years old when he found out that he was Ainu. Thanks to rigorous assimilation policies, the Ainu in Japan bear more resemblance to ethnic Japanese than past generations. Because of the ugly legacy of discrimination, however, the true number of Ainu still left in Japan is unknown. Due to fear, many of the Ainu have chosen to hide their background, leaving younger generations with limited if any knowledge about their heritage. The Ainu language is also at risk of extinction.

Although the bill became law in August 2019 and Tokyo University returned some of the robbed remains the following year, the fight for the Ainu people’s rights is just beginning. Despite widespread recognition and gradual acceptance of the Ainu, some feel the Ainu culture is at risk of tokenization. Though the preservation of Ainu culture is commendable, the Ainu’s future should also be considered if they are to have a chance at survival.

Rhiannon Koh

Rhiannon earned her B.A. in Urban Studies & Planning from UC San Diego. Her honors thesis was a speculative fiction piece exploring the aspects of surveillance technology, climate change, and the future of urbanized humanity. She is committed to expanding the stories we tell.

Aotearoa: Reclaiming Maori Language and Identity in New Zealand

Compared to Indigenous groups around the world, the Maori in New Zealand enjoy more agency because of the Treaty of Waitangi, a founding document that recognizes Maori ownership of land and their subsequent autonomy in the country’s government. However, some feel that more can be done to create a bicultural and celebratory society—one that puts the Maori language at the forefront.

A performance of the haka, a traditional Maori dance. Matthieu Aubry. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

New Zealand is an island country known for its scenic views, its native kiwi bird and its iconic role as the fictional Middle Earth. The country, named Aotearoa (meaning “long white cloud”) in the Maori language, is also steeped in rich history and culture.

Before European settlement, New Zealand was home to the Maori, one of the region’s many Polynesian ethnic groups. According to their oral histories, the Maori first voyaged from present-day Tahiti. They arrived and began inhabiting Aotearoa as early as 1300 A.D. Once settled, the Maori formed tribal societies. Their culture revolves around respect for the natural environment. The Maori also possess elements of a warrior culture—they craft unique performative arts such as the haka, a war dance turned into a ceremonial celebration.

Although the first Europeans—Dutch navigators—made contact with the Maori in 1642, the Maori way of life was not significantly impacted until the late 1700s. With the arrival of British Capt. James Cook, the scramble for New Zealand ensued. As nearby French voyagers and ungoverned sealers and whalers reaped profits from the islands’ natural resources, the British moved to make New Zealand a colony in 1840.

Reconstruction of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Archives New Zealand. CC BY 2.0

In that same year, the Treaty of Waitangi was created. This artifact is not only recognized as a founding document but also as one that acknowledges Maori rights to the land. Despite its contentious nature, the Treaty of Waitangi is still considered a key success for the treatment of Indigenous people in New Zealand. In countries like Canada and Australia, Indigenous groups suffer a lower quality of life and enjoy less autonomy than their counterparts in New Zealand. These disparities can be traced back to the absence of a document acknowledging Indigenous people’s land rights.

Although the status of the Maori in New Zealand may be considered a model for Indigenous treatment across the globe, there are still discrepancies that prevent them from fully embracing their dual identities. Though Maori is considered one of the national languages and has been celebrated every September since 1975, a national study found that only 148,000 people in New Zealand can hold a conversation in it.

In a piece for The Guardian, Leigh-Marama McLachlan explains her rejection of Maori culture to sustain success in New Zealand. She writes, “Back then, almost no one in my family spoke [Maori]. My grandmother was like so many Maori of that generation who were led to believe that our language would be of no use to their children.” Although McLachlan possesses some rudimentary Maori, she laments the overwhelmingly monolingual sentiment of the country.

The personal rejection of Maori culture can be traced back to the early stages of New Zealand’s modernization. In a 2015 study, Maori education professors Lesley Rameka and Kura Paul-Burke found that education for children dismissed the value of Maori. Textbooks failed to frame Maori history in a positive light, rendering the culture and language as “unintellectual, trivial and strange.”

A Maori carving. Bernard Spragg.

Since the last Maori Language Week in September, some feel that it is time to restore places to their rightful Maori names. Since the protests against racial injustice in the United States, policymakers and stakeholders were forced to reexamine New Zealand’s racist past of colonialism and disenfranchisement. With an overall renewed interest in Maori rights and treatment, several telecommunications firms in the country have already changed their names to include “Aotearoa.”

Rhiannon Koh

Rhiannon earned her B.A. in Urban Studies & Planning from UC San Diego. Her honors thesis was a speculative fiction piece exploring the aspects of surveillance technology, climate change, and the future of urbanized humanity. She is committed to expanding the stories we tell.

TikTok logo against a blue sky. Kon Karampelas. CC BY.

Indigenous Creators Raise their Voices on TikTok

On TikTok, the social media app with over 800 million users worldwide, Indigenous creators have found a platform. Amplifying Indigenous narratives that are often unheard, creators share culture, history and daily life with their followers. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Indigenous creators have also utilized the app to illustrate how the virus disproportionately affects Native Americans. As a platform, TikTok offers users small clips of content, lending accessibility to information often unavailable in mainstream media.

James Jones, a member of Canada’s Cree Nation, is a creator, dancer and Indigenous performer who uses TikTok as a platform for awareness and advocacy. His videos show users the basics of hoop dancing and the intricacies of tribal regalia used for ceremonial purposes. Jones told Vogue: “We dance for those who can’t dance, and we dance to heal. I always hope to educate and bring awareness in a good way.”

Theland Kicknosway is a 17-year-old Cree creator who uses his platform to connect with other Indigenous teens and spread awareness of Indigenous culture. In his series on braids, he teaches users about the sanctity of hair in Indigenous culture. Kicknosway educates viewers on the grim treatment of Indigenous people in both the present and the past while empowering Indigenous men to wear their braids proudly.

Lila Bible is a Native American teen working to bring awareness to the ongoing plight of missing Indigenous women across North America. Indigenous women are subjected to violent crimes at a rate as high as 10 times the average across many parts of the United States. In her videos, Bible emphasizes the need to advocate for these missing women, using her personal narrative as a touchstone.

Jojo Jackson is another creator who works to dismantle preconceived notions of Native American communities. He went viral in April 2020 with a video illustrating the harsh impact that the coronavirus has had on the Navajo Nation. Jackson told The Guardian that he “just wanted to spread awareness, to give people basic, raw information because I thought the news was sugarcoating it. I wanted to show what it’s like [on the reservation], the number of COVID-19 cases and the basic resources the Navajo Nation just doesn’t have.”

Sarah Leidich

Sarah is currently an English and Film major at Barnard College of Columbia University. Sarah is inspired by global art in every form, and hopes to explore the intersection of activism, art, and storytelling through her writing.

VIDEO: Indonesia's Mentawai Tribe

To give Joshua Cowan’s film even deeper meaning, it’s important to understand context. Mentawai is an archipelago found off the west coast of Sumatra (Indonesia) consisting of approximately 70 islands and islets. The history of the people is often debated, but as early as 1954, under Indonesia’s goal of national unity and cultural adaptation, the National Government began introducing civilization programs designed to integrate the tribal groups into the social and cultural mainstream of the country. This, for native Mentawai, meant the eradication of Arat Sabulungan — the animist belief system that links the supernatural powers of ancestral spirits to the ecology of the rainforest — ; the forced surrender, burning and destruction of possessions used to facilitate cultural or ritual behavior; and their Sikerei (shamans) being disrobed, beaten, and forced into slave labor and imprisonment.

Under Pancasila — the official, foundational philosophical theory of Indonesia — the Indonesian state should be based on the Five Principles: Indonesian nationalism; Internationalism, or Humanism; Consent, or Democracy; Social prosperity; and Belief in One God. Based on the Indonesian notion ‘belief in one God’, there are officially only five religions recognized: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Which, for the Mentawai Islands, resulted in an immediate influx of missionaries and an increase in violence and pressure on the people to adopt change. In the end many chose Christianity due to its flexible views on the possession and consumption of pigs, which play an integral role in Mentawai history and culture.

By the late 1980’s loggers had devastated the forests of Sipora, North and South Pagai. In 1980, WWF (World Wildlife Fund) published a report entitled ‘Saving Siberut’ which, along with the support of other organizations – primarily UNESCO and Survival International – and other additional international interest, helped persuade the Indonesian government to cancel logging concessions and declare the forests of Siberut a biosphere reserve. With this, the people in the Mentawai found that they were once again free to practice their native cultural activities – at least in areas away from the villages.

However, by this point, and as it remains today, the number of Indigenous people still actively practicing the cultural customs, rituals and ceremonies of Arat Sabulungan had already been limited to a very small population of clans primarily located around the Sarereiket and Sakuddei regions in the south of Siberut Island.

Raeann Mason

Raeann is an avid traveler, digital storyteller and guide writer. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Mass Comm & Media Studies from the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism & Mass Communication. Passionate about a/effective journalism and cultural exchange, she is an advocate of international solidarity and people's liberation. As the founder of ROAM + WRITE and EIC of Monarch Magazine, Raeann hopes to reshape the culture of travel and hospitality to be ethically sound and sustainable.

As Acai Demand Rises, Amazonian Communities Seek Out their Role

The acai palm is one of the many native plants that has been commodified for Western consumption. This has shifted acai consumption and production practices within Indigenous Amazonian communities.

Acai bowls are the most common form of Western acai consumption. Ella O, CC BY 2.0

Prior to 2000, Indigenous Amazonian communities utilized the acai palm plant on a local scale. The purple berry then found its way to the U.S., appealing to surfers in Hawaii and Southern California. It has since been in the spotlight, spurring new industries and finding its way into the global marketplace. The acai palm plant is one of many Indigenous plant foods that has been commodified for foreign consumption, shifting acai usage and production practices among Brazil’s Amazonian tribes. Indigenous Amazonian communities, who have utilized acai as a diet staple for centuries, are now exporting it for profit, hoping not to forfeit their land to multinational corporations.

Companies that sell acai heavily market its health benefits, calling it a superfood that allows individuals to reach maximum health. Acai specifically offers anti-aging benefits, improved digestive health, increased energy levels and a strengthened immune system. The berry contains high amounts of antioxidants, omega-6 and omega-9 fatty acids, fiber, protein, vitamins and minerals. When globally transported, the acai berry is processed and packaged into various forms. When reduced to powders, capsules and liquids, the acai berry becomes a watered-down entity detached from Amazonian food culture. While many understand acai’s countless health benefits, few consumers know the context from which it comes.

Grown on tall acai palm trees, the acai berry sprouts in large, clustered bunches. The trees grow to between 50 and 100 feet tall, bearing the fruit from their extended branches. In the village of Acaizal on the Uaca Indigenous reserve, villagers loop a palm leaf tied around their feet and scale the tree, knife gripped firmly between their teeth. Children, some as young as seven, learn this harvesting method. Once collected, acai pulp is served chilled and often mixed with sugar and tapioca.

Increased demand for acai pushes Indigenous groups to formalize and industrialize this cultivation process. Amazonian tribes subsequently alter their traditional production to accommodate increased consumption. In the state of Amapa, Indigenous communities want to explore potential business arrangements and have identified acai production as a top priority for natural resource management. In a workshop hosted by local government agency Secretary Extraordinary of Indigenous People, Acaizal village chief Jose Damasceno Karipuna learned how to capitalize on acai harvesting processes. The increase in acai demand creates a flourishing job market for large-scale Amazonian farmers; however, it harms farmers who rely on small-scale production. With an ever-increasing demand for acai, protection of natural areas is crucial to preservation. For the villagers in Acaizal, proper environmental management will increase productivity while ensuring sustainability. Acai companies emphasize this business exchange as mutually beneficial, bettering individuals’ health and the Brazilian economy alike. However, the mass consumption and commodification of acai is ultimately a gray area, creating an uncertain future for Indigenous communities.

Anna Wood

Anna is an Anthropology major and Global Health/Spanish double minor at Middlebury College. As an anthropology major with a focus in public health, she studies the intersection of health and sociocultural elements. She is also passionate about food systems and endurance sports.

Group of Aboriginal children in the early 1900s. Kay- Aussie~Mobs. Public domain

The Continued Abuse of Australia’s ‘Stolen Generation’

The term “Stolen Generation” was coined after deeply discriminatory government policies were passed in Australia between 1910 and 1970. This was due to the fact that many Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes under the pretense of “assimilation” into “white society.” Assimilation was based on the “assumption of Black inferiority and white superiority, which proposed the Indigenous people should be allowed to ‘die out’ through a process of natural elimination or, where possible, assimilation into the white community.” This tragedy led to children being torn from their families, taught to reject their culture, forced to not speak their native languages and required to adopt white culture in new white families they were brought into.

Aboriginal people of white parentage, known at the time by the derogatory term “half-castes,” were most at risk of being removed from their homes since it was thought they would be easier to assimilate into white culture because of their lighter skin. Many were abused and neglected, and they received minimal education due to the assumption that the highest they would go was indentured servitude or work as manual laborers. The ensuing trauma has caused both the children and families mental trauma while the continued societal abuse such as stolen wages and racial discrimination was and still is prevalent. This is especially evident in statistics such as incarceration numbers and yearly wages. After George Floyd’s death, “debate raged about Australia’s own history.” By looking into the Australian national statistics, it was revealed the distrimination from back in the early 1900s has continued into the present.

Stolen Wages Still Prevalent Today

“Back in the early 1970s, Aboriginal people living in remote areas were being paid as little as 19% of the non-Aborginial population.” The average Indigenous income is roughly only 44% of the median non-Indigenous income, though the gap is starting to close for the 37% of the Indigenous population living in Australia’s major cities. 20% of the Indigenous population living in cities is still living in poverty, though, along with more than half of those living in rural areas. Even more concerning, “about 10% of the Indigenous population also received no income at all and that includes government payments. It is unclear how these people survive.”

Largest Incarcerated Population in the World

An even more shocking statistic was found in 2018 that “100% of children being held in youth detention in the (Northern) Territory are Aborginal.” They are currently the most incarcerated people in the world - not always for committing crimes. Tanya Day was arrested for sleeping on a train, later dying from repeated head injuries in jail. Additionally, a woman named Ms. Dhu was found dead in jail due to untreated injuries caused by prior family violence and abuse. The coroner said her medical care was “deficient” since the police refused to treat her, believing she was “faking it.” There have been serious concerns about racial profiling that have been directly correlated to arrests made - and the arrests not made. It was found that “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up about 2% of the general population but represent 28% of those in prison.” It has been estimated that in the last 29 years, one Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island person has died every three weeks in jail.

Higher Levels of Domestic Violence, Abuse and Poverty

Another impact of Aboriginals being forced to assimilate into white communities is a staggering amount of domestic violence and abuse. Aboriginal women are 34 times more likely to be hospitalized from domestic abuse; however, when Aboriginal women try to call police for help, they are often arrested instead for defending themselves. This has also led to the statistic that Indigenous people have a lower life expectancy than the average non-Indigenous person, by an estimated 9 years. This has been blamed on factors such as poverty, poor health care, lack of healthy food, low living standards and more.

The reality of today’s society in Australia is the hidden discrimination that started in the early 1900s and prevails even today. With the recent global reaction to racial discrimination and slavery, a closer look into Australia’s history has revealed these revelations that have often been covered up and disputed. Efforts to increase awareness of the current state of affairs in the country have been underway and protests continue despite an absence of widespread media coverage.

Elizabeth Misnick

Elizabeth is a Professional Writing and Rhetoric major at Baylor University. She grew up in a military family and lived in Europe for almost half her life, traveling and living in different countries. She hopes to continue writing professionally throughout her career and publish her writing in the future.

Colombian soldiers. Alejandro Turola. Pixabay.

Outrage Mounts as Colombian Soldiers Admit to Rape of an Indigenous Girl

On June 25, seven soldiers of the Colombian army confessed to raping a 13-year-old Indigenous girl from the Embera tribe. She was discovered at a nearby school after having gone missing from her home in the department of Risaralda on June 21. Upon seeing that the young girl could barely walk, she was sent to a hospital and then forensic services along with receiving assistance from the Organization of Indigenous Nations of Colombia (ONIC). Luis Fernando Arias, senior adviser for ONIC, told CNN that the girl “was kidnapped and raped for a period of 17 hours.” The Embera community requested that the soldiers be tried under their own laws along with ONIC “demanding that they be tried under Indigenous law, arguing that it's their jurisdiction since the alleged crime was against an Indigenous person, on Indigenous land.”

Since the alleged rape, the seven men accused were fired along with three of their superiors. The country’s attorney general, Francisco Barbosa, stated that if found guilty the men could face 16 to 30 years in prison, but Colombian President Ivan Duque urged a life sentence for the accused soldiers. He stated that, “If we have to inaugurate the life in prison penalty with them, we're going to do it with them. And we are going to use it so that these bandits and scoundrels get a lesson.” Although many are asking for the imprisonment of the soldiers, Gimena Sanchez, Andes director of the think tank Washington Office on Latin America, believes that, “There needs to be education and consciousness raising within the armed forces on how to treat and how to engage with ethnic minorities. Not just with Indigenous but also Afro-Colombians.”

The country’s response was that of fury, albeit bereft of shock due to the long-standing systemic issue of soldiers' abuse and violence against Indigenous women and girls in Colombia. On July 2, after pressure mounted and Indigenous groups held protests against the gender-based violence of Indigenous women, Colombian Army Commander General Eduardo Zapateiro publicly disclosed that 118 soldiers had been investigated due to incidents of sexual violence against minors since 2016, and of those only 45 have been fired. Despite these statistics, Zapateiro stated that, “These abuses are not systemic conduct. Understand that we are 241,000 men, who every day give everything for the Colombian people.” His argument is that this is not a systemic issue but since the reporting of this story, other cases of sexual violence against Indigenous girls have emerged. One case that was not widely reported until now reveals that a 15-year-old girl from the Nukak Maku Indigenous tribe was kidnapped, tortured and raped in the military barracks of troops in the southern Guaviare department.

Colombia is not exempt from the pandemic of sexual violence that affects women all over the globe but following a vote against a peace referendum to end the conflict in Colombia, women are disproportionately enduring violence on a systemic level. Colombia has the 10th highest rate of femicide in the world, according to U.N. data. The Colombian Femicide Foundation documented that “8,532 women and girls reported that they had experienced sexual violence in the first five months of this year. More than 5,800 were under the age of 18.” The outcome of this case may bring hope to those who want to see justice in the form of imprisonment, but the culture that normalized violence toward women remains.

Hanna Ditinsky

is a sophomore at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is majoring in English and minoring in Economics. She was born and raised in New York City and is passionate about human rights and the future of progressivism.

A June 6 anti-racism protest in Brisbane, Australia. Andrew Mercer. CC BY-SA.

‘Same Story, Different Soil’ as Police Brutality Hits Home for Indigenous Australians

Joining millions of activists around the globe, tens of thousands of Australians have taken to the streets over the past two weeks to stand in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. However, for many of these protesters, the demonstrations are about more than standing in solidarity with their American counterparts — Australian activists have used the movement to place an international spotlight on Indigenous Australian deaths in police custody.

According to The Guardian’s database on Indigenous Australians’ deaths in custody from 2008 until today, 164 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had died while in police custody. As of June 2018, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 28% of Australia’s prison population, despite making up 2.8% of the country’s total population as of the 2016 census.

This widespread issue draws parallels to police brutality against African Americans in the United States. While no official data has been released on deaths in police custody in the U.S. despite the passage of the 2013 Death in Custody Reporting Act, African Americans in 2019 were 2.5 times more likely than white Americans to be killed by police officers. Broken down, 24% of all police killings in the U.S. in 2019 were of African Americans, despite only 13% of the nation’s population identifying as black.

Many Australian activists were further galvanized to take to the streets after a video surfaced of a Sydney police officer slamming an Indigenous boy to the ground on June 1. This video is similar to the countless ones in the United States which have documented instances of police brutality.

These activists have expressed how the issues in the United States and in Australia are one and the same. “It’s the same story on different soil,” 17-year-old activist Ky-ya Nicholson Ward said during a June 6 rally in Melbourne.

Justin Grant, an activist who attended the Melbourne rally, spoke on the historical relationship between the police and Indigenous Australians in an interview with Al-Jazeera. “[The police] are breaking our trust and scaring our people ... they [don't] respect our culture, our laws or our practices."

These parallels have been emphasized during the protests, with chants such as “I can’t breathe” taking on new meanings outside of their American context. Several protesters’ signs have echoed this sentiment, with phrases such as “Same Story, Different Soil” popping up on protest materials throughout the country.

However, others have diminished the similarities between the motivations behind the Black Lives Matter movement and Indigenous Australian deaths in police custody. Prime Minister Scott Morrison said during an interview with local Sydney radio station 2GB that: “There’s no need to import things happening in other countries here to Australia … Australia is not the United States.”

Black Lives Matter protests both within Australia and around the world are expected to continue throughout the coming weeks. As of this article’s publication, there have been no major responses to the protests within the Australian Parliament House to address Indigenous deaths in police custody.

Jacob Sutherland

Jacob is a recent graduate from the University of California San Diego where he majored in Political Science and minored in Spanish Language Studies. He previously served as the News Editor for The UCSD Guardian, and hopes to shed light on social justice issues in his work.

A family compound in the Navajo Nation. Don Graham, AZ 9-15

History Repeats Itself as the Navajo Nation Faces COVID-19 Neglect

In the coronavirus pandemic, the Navajo Nation has seen the highest per capita rate of COVID-19 infection rates in the U.S., surpassing densely populated, urban hotspots. As of May 31, there have been 5,348 positive cases and 246 deaths out of 173,000 residents. These infections stem from governmental neglect and underfunding, as many in the Navajo Nation lack running water, COVID-19 resources and federal assistance. Additionally, preexisting health conditions and lifestyle factors prominent within the Navajo Nation render its residents especially vulnerable to the virus. Homes are often cramped with several generations of families, and lack of food access elicits widespread dietary illnesses on the reservation.

"You got the feds, you got everybody saying, 'Wash your hands with soap and water,' but our people are still hauling water,” said Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez in a digital town hall meeting on May 12. Roughly 40% of Navajo homes do not have running water, and 10% do not have electricity. This conflicts with guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention which call for the thorough washing of hands. Although the Navajo Nation government has called for mask wearing and issued lockdown curfews, it cannot implement all preventative measures ordered by the CDC. Respiratory complications are also brought on by indoor pollution, as Navajo homes are often heated with wood and coal.

The largest Native American reservation in the U.S., the Navajo Nation contains 173,000 people. Its 27,413 square mile semi-autonomous territory spans across parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. Like all Native Americans, the Navajo people have faced generations of genocide, dispossession, and forced relocation that came with colonization. Mark Charles, a Native American activist and U.S. presidential candidate, traces disproportionate infection and death rates to the inequities caused by settler colonialism. “It's a problem 250 years in the making, going back to how this nation was founded. The ethnic cleansing and genocidal policies … that's where the problem lies. Health care is poor, treaties are not being upheld,” he told Al-Jazeera.

Indeed, the COVID-19 outbreak parallels previous epidemics, such as smallpox, the bubonic plague, and Spanish flu that devastated indigenous peoples. The Navajo Treaty of 1868, signed by the Navajo and U.S. government, promised federal support to the Navajo Nation, including health care, infrastructure and water access. The U.S. government has since then failed to uphold this treaty. The $8 billion relief package for Native American communities, prompted by the COVID-19 stimulus bill, was only put to use by mid-May, long after the initial outbreak. This delay in funding left essential workers without protection, and led to a shortage of critical resources in health facilities.

Preexisting health conditions brought on by reservation lifestyle habits highlight the social determinants of health that have been continuously exacerbated in communities of color. Specifically, European colonization hindered Native Americans’ agricultural methods and eating practices, resulting in current diet-related illnesses. Since the mid-1900s, reservation bound Native Americans have experienced problematic blood sugar levels, obesity, diabetes and cardiac stress. American Indian adults are over three times more likely than non-Hispanic white adults to be diagnosed with diabetes, and over 50% more likely to be obese. According to CDC data, about half of the hospitalized coronavirus patients are obese, and face higher risks of severe illness.

Anna Wood

Anna is an Anthropology major and Global Health/Spanish double minor at Middlebury College. As an anthropology major with a focus in public health, she studies the intersection of health and sociocultural elements. She is also passionate about food systems and endurance sports.