Hokkaido boasts some of Japan’s most stunning natural beauty, with its national parks, fresh seafood and powder snow.

Read MoreArchitecture That Targets the Unhoused in Japan

Japan’s unhoused crisis is masked by urban design called hostile architecture, a tool used to alienate those experiencing homelessness, affecting the public in the process.

Read MoreDon’t Eat and Walk: Japan’s Rule That Leaves Travelers Confused

The Japanese value of staying in the moment and being mindful grounds the custom of not eating and walking simultaneously.

Read MoreThe History Behind Japan’s Women-only Trains

With the need to address transit safety and security, these pink-labeled train cars are Japan’s solution.

Read MorePod Culture in Japan: Exploring the Quiet World of Capsule Hotels

A close-up tour of Japan’s high-tech sleep culture across three iconic cities.

Read MoreComfort or Cruelty? The Buried Truth of Imperial Japan’s Sexual Slavery

Thousands of women were forced to work in “comfort stations” during World War II and their persistent fight for justice continues today.

Read MoreThe Truth about Geisha Tourism in Japan

Japan’s geisha have survived war and the turn of the century — unruly travelers may be the dying art’s final blow.

Read MoreMatcha's Roots: The Legacy of Japan's First Tea Tree

Explore Shofuku-ji, Japan’s oldest Zen temple, where the legacy of the first tea tree still thrives.

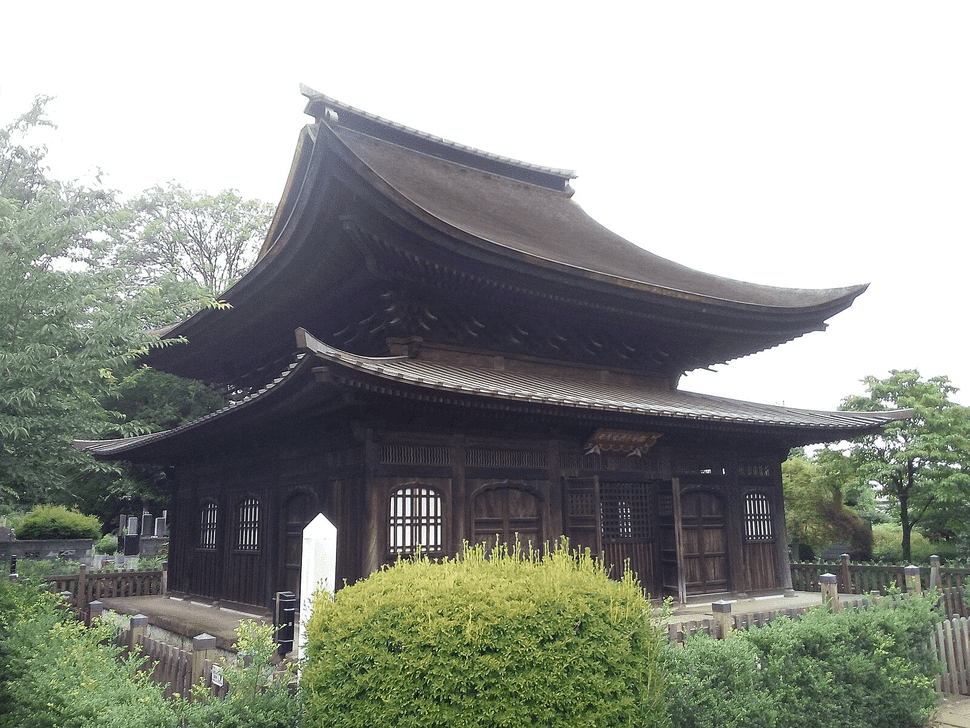

Shofuku-ji Temple. N yotarou. CC BY-SA 4.0

At the end of an unassuming street in Fukuoka, Japan stands the Shofuku-ji Temple. Its ancient grounds are a testament to centuries of cultural and spiritual history, particularly to the evolution of matcha, Japan’s iconic powdered green tea. Matcha is made from specially grown and processed tea leaves. The process begins with shading the tea plants several weeks before harvest to boost chlorophyll levels, resulting in its vibrant green color. The leaves are then carefully picked, steamed to stop oxidation, dried, and ground into a fine powder using traditional stone mills. Matcha's popularity outside Japan, especially in the U.S., experienced a surge in the early 21st century due to a growing interest in health and wellness globally. Its high antioxidant content, culinary versatility, and cultural appeal contributed to its widespread adoption in cafés and homes worldwide.

Shofuku-ji Temple was founded in 1195 CE by the Buddhist priest Myōan Eisai, who is often credited with introducing Zen Buddhism to Japan. However, Eisai’s cultural influence extends beyond religion. Chinese legend dates the invention of tea to around 2737 BCE in ancient China. From China, the beverage was brought to Japan by a mission of monks, including Eisai, returning from a pilgrimage in 1191 CE. Upon arriving in Japan, Eisai cultivated the tea seeds in the Iwakamibo gardens of Ryozen-ji Temple, Saga.

Shofuku-ji Temple Pond. Mark Pegrum. CC BY 2.0

These seeds, which produced the first tea plants in Japan, became the foundation of what is now known as matcha. The plant that stands at Shōouku-ji today, often referred to as "Japan’s First Tea Tree," is a direct descendant of those original plants, a living monument to the history of Japanese tea culture.

When Eisai brought the tea seeds to Japan, he was not merely bringing a new beverage, he was introducing a practice that would become integral to the Zen way of life. The preparation and consumption of matcha evolved into a ritualized practice that aligned perfectly with the principles of mindfulness and presence central to Zen.

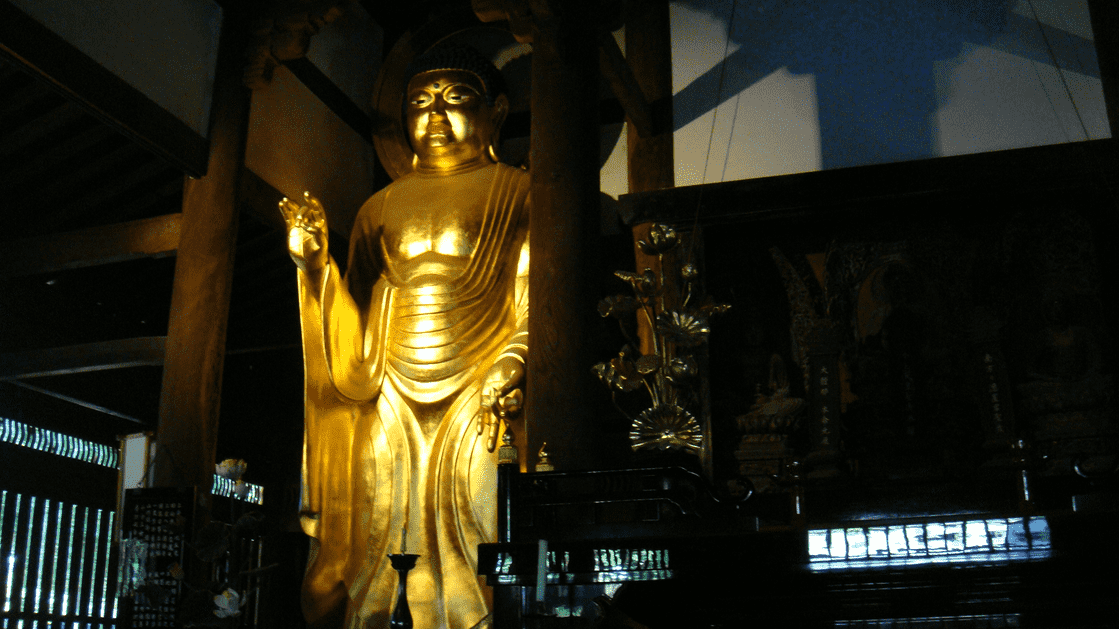

Buddha Statue. David McKelvey. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Referred to as “the way of tea,” the preparation of tea developed into an exercise of Zen devotion that honored the beauty which can be discovered in an otherwise flawed world. Author and tea expert Solala Towler has said: “It is a ceremony that takes the simple art of drinking tea to a sacred level, where the host and the guests share a moment of worship of the simple art of preparing and drinking of tea together, elevating them to a level of purity and refinement.”

The Jizōdō at Shōfuku-ji. MomoyamaResearch. CC BY-SA 4.0

The word matcha comes from the Japanese verb “matsu”, (to rub or to daub) and “cha” , (tea). In its early form, matcha was consumed as a medicinal drink. Eisai himself wrote about the health properties of tea in his book “Kissa Yojoki” (“Drinking Tea for Health”), where he extolled the virtues of tea for both body and mind.

Eisai believed that tea could cure physical ailments and enhance mental clarity and spiritual well-being, making it an ideal companion for Zen meditation. He realized that drinking matcha improved his meditation sessions by producing a state of calm alertness, likely a product of the cognition-boosting interaction between matcha’s caffeine and L-theanine. Caffeine, a natural stimulant, provides an energy boost. However, caffeine alone can sometimes lead to jitters, increased heart rate, or anxiety. L-theanine, an amino acid found in tea leaves, counters this with its calming effect on the brain. It promotes the production of alpha waves, which are associated with a relaxed yet alert mental state.When consumed together in matcha, caffeine and L-theanine synergize to create a balanced effect.

Shofuku-ji Temple. David McKelvey. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

For centuries, the practice continued to spread throughout Japan, dispersing throughout all levels of society. Today, the matcha tea ceremony provides an opportunity for intellectual exchange, the sharing of knowledge and the continuity of tradition.

As was written in a collection of essays entitled “The Book of Tea” by Okakura Kakuzo, one of the first Japanese to advocate for the art of tea drinking, “Those who cannot feel the littleness of great things in themselves are apt to overlook the greatness of little things in others,” a sentiment that ties humility in oneself to the appreciation of others and their work, tea among them.

A Sanmon at Shofuku-ji Temple. STA3816. CC BY-SA 3.0

Today, Shofuku-ji Temple remains a serene sanctuary where visitors can connect with the historical and spiritual origins of matcha. The temple grounds, with their carefully maintained gardens and ancient structures (including a Buddhist temple, a kitchen, a Zen hall, a bell tower, a sun and moon garden, a records hall, and more) provide a peaceful setting for reflection upon the past. Visitors can appreciate the tea plant, a living link to Japan’s first tea plants, and the enduring legacy of Eisai’s contributions to Japanese culture.

Generally, Shofukuji Temple is not open to the public. If you are visiting as a group, you must apply one month in advance and receive permission from the temple, even if you just wish to tour the grounds. The application and a guide to the grounds can be found on the temple’s website. The temple is a nationally designated historic site that protects cultural assets and the continuation of the Zen tradition, so visitors are asked to proceed quietly and with care. Visitors may also be asked for a contribution to help protect and restore cultural properties. Applications received less than one month in advance will not be accepted.

GETTING THERE

Shofukuji Temple can be reached in a short walk from Gion Station and a 15-20 minute walk from Hakata Station in Fukuoka. Fukuoka is the sixth largest city in Japan and offers a variety of hotels and transportation methods for visitors.

Rebecca Pictairn

Rebecca studies Italian Language and Literature, Classical Civilizations, and English Writing at the University of Pittsburgh. She hopes to one day attain a PhD in Classical Archeology. She is passionate about feminism and climate justice. She enjoys reading, playing the lyre, and longboarding in her free time.

A Trip Through the Past: Japan’s Living Heritage on Sado Island

The historical music, performing arts and cuisine are kept alive on a tiny resort island off the Japanese coast.

A Noh performance onstage on Sado Island. Yoshiyuki Ito, CC BY-SA 3.0

Feudal Japanese history gave rise to one of the most fascinating cultures in the world. Decades of relative isolation on the islands of Japan allowed for a completely unique society to blossom, and the resulting art, music and performance is incredible to behold. Although the world has largely moved on from the 18th century, there are still small pockets of society that try to keep those cultures alive. And there is no better place to see Japan as it once was than on Sado Island.

Sado Island was not always beautiful. In the beginning, it was used as a prison colony for political exiles from nearby Japan. Around 1601, however, the territory's rulers discovered a massive vein of gold running through the island. This naturally led to a gold rush, which jump started the population of Sado. The mine lasted for over 400 years, closing at last in 1989. After this, the population began to decline, and now the island has gone from a mining hub to a lush resort.

Today, Sado is a massive cultural hotspot. Throughout history, Sado Island was a crucial trading base on the way to Osaka—this resulted in a huge number of cultures leaving their mark on the land over centuries. Ancient Buddhist shrines and feudal Japanese temples share space across the island, as architecture from all eras fills in the gaps.

The city of Shukunegi, for instance, has been around for over 400 years—it was constructed during the beginning of the Edo era in the 1600s. Many of the buildings were actually built from wood and stone brought by or recycled from the trading ships themselves. Many of these structures are still standing today, packed tightly together to form blocks of houses.

However, the heart of Sado’s cultural preservation comes in the form of its performing arts and music. Noh, a traditional style of Japanese theater, is typically performed in shrines, with the audience sitting outside around bonfires. The stages are open on three sides, with the back featuring a painted image of pine trees. The lead performer typically wears a mask, fashioned after the leading characters of the play (although they are also used to denote spirits and demons). There is nothing in the world quite like Noh, and Sado Island is one of the best places to watch these magnificent performances in person.

Another example of classic Japanese culture on Sado Island is onidaiko, which literally translates as “demon drumming”. These performances include masked dancers and the famous music of Japanese taiko drumming, which was traditionally used to ward off negative energy and spirits during rice harvests. Taiko is most prominent during the Earth Celebration, which takes place in the middle of August every year and lasts for three days of music, performances, and culture. The Sado Island Taiko Centre, where visitors can see taiko drumming year-round, is home to two of the biggest taiko drums in the world.

In addition to its vibrant culture and rich history, Sado Island is a simply gorgeous natural vista. It boasts over 170 miles of coastline, with everything from nearly 100-foot cliffs and volcanic rock walls to lovely beaches. The island is also home to a wide variety of rare plants and animals, including the toki, also called the crested ibis, an extremely rare bird that has become the unofficial mascot of Sado. Even if you’re more in the market for nature than culture, there’s an incredible amount of both to be found on Sado.

Sado has a large number of hotels all over the island, ranging in price from $99 to $500. The island is a wonderful travel destination year-round, but the best time to go is mid-August in order to catch the Earth Celebration.

Ryan Livingston

Ryan is a senior at The College of New Jersey, majoring in English and minoring in marketing. Since a young age, Ryan has been passionate about human rights and environmental action and uses his writing to educate wherever he can. He hopes to pursue a career in professional writing and spread his message even further.

A Festival of Flight: Explore Japan’s Hamamatsu Kite Festival

Join more than 1.5 million people in May to celebrate the Hamamatsu Kite Festival.

Kites flying during the Hamamatsu Kite Festival. Shizuoka Prefectural Tourism Association. CC BY-SA 2.1 JP

The origins of the Hamamatsu Kite Festival date back more than 450 years. In Japan, kites have been used for both practical and celebratory purposes for over 1,000 years. During the Edo era, kites were flown to celebrate the birth of a first-born son. This tradition then developed into the Hamamatsu Kite Festival where all children are celebrated.

At the beginning of May during Golden Week, Hamamatsu’s skies are filled with over 100 vibrant, traditional kites. The designs of the kites in the Hamamatsu Kite Festival symbolize children and traditions from each town in the district of Hamamatsu. The kite fliers then partake in an aerial battle, attempting to sever each other's kite strings.

As dusk falls, the festivities move from the beach to the city center where the streets come alive with dance and musical performances featuring bells and drums. The traditional music follows nearly 100 artfully decorated floats as they travel through the streets of Hamamatsu. The floats carry children in customary clothing and are pulled by cheering adults with lanterns and flags in hand.

Some floats are over 100 years old, and travelers can learn about their history at the plaza between the JR-Hamamatsu and Shin-Hamamatsu train stations where a few floats are displayed throughout the day. There are three parade routes, so for those hoping to see all the floats it is recommended that they choose a different route each night.

The location of the kite battles on the Pacific coastline allows travelers easy access to other nearby marvels, such as one of three of Japan’s major sand dunes. The Nakatajima Dunes, known as a famous hatching ground for loggerhead sea turtles, can be found near the kite battles, and are surrounded by coastal forests.

Not only home to its eponymous Kite Festival, the city of Hamamatsu is a destination known for its diverse landscapes and impeccable craftsmanship. Along with the coastline, Hamamatsu boasts mountains, a river and Lake Hamana, the birthplace of Japan’s eel-farming industry. Energetic travelers can participate in many activities at Lake Hamana, including windsurfing, swimming and biking.

Nature lovers will feel right at home among thousands of plant species at the Hamamatsu Flower Park. History buffs can learn about the city’s musical history at the Hamamatsu Museum and explore Hamamatsu Castle.

Hamamatsu is easily accessible from Tokyo. Travelers can take a bullet train from Tokyo Station to Hamamatsu Station in as little as 100 minutes.

Madison Paulus

Madison is a student at George Washington University studying international affairs, journalism, mass communication, and Arabic. Born and raised in Seattle, Washington, Madison grew up in a creative, open-minded environment. With passions for human rights and social justice, Madison uses her writing skills to educate and advocate. In the future, Madison hopes to pursue a career in science communication or travel journalism.

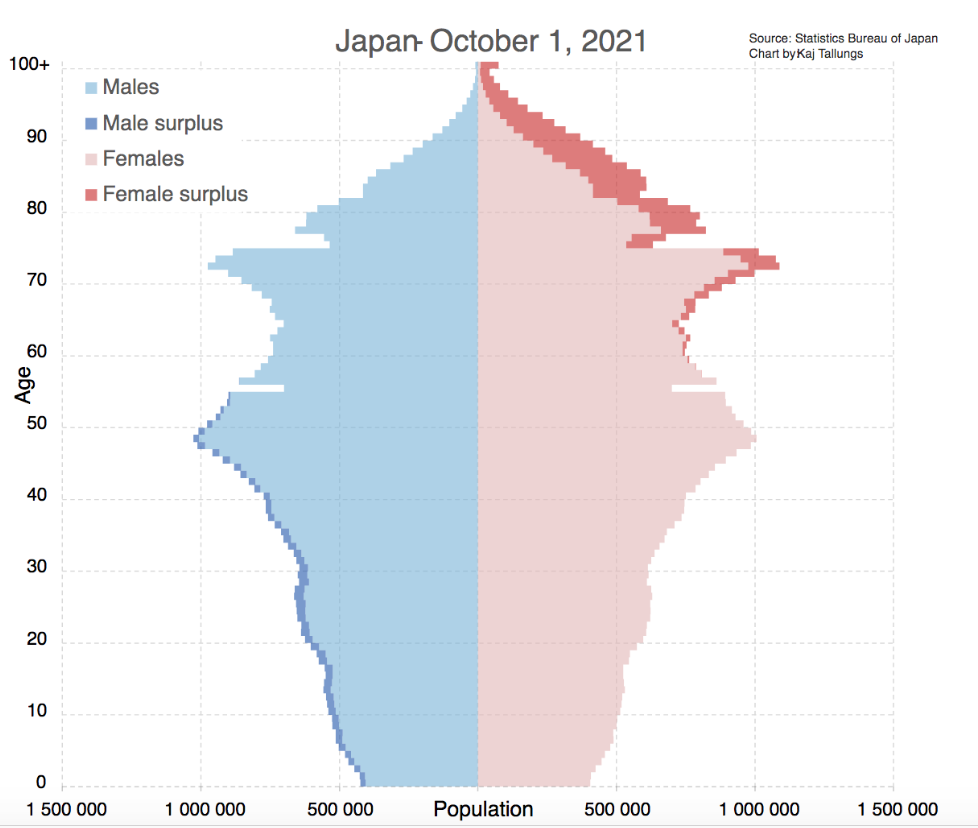

Japan’s Population Crisis Hits a Record Low

Japanese birth rates are falling exponentially, and it could have major effects on the country’s economy.

Harajuku District in Japan. @paulkrichards. Instagram

Many around the world consider Japan a futuristic country, a view drawn from its creative technology and its unique culture. A popular destination for tourists all around the world, this East Asian country makes up 1.6% of the world’s population with its approximately 125 million residents.

However, this number is set to rapidly decline as Japan teeters on the precipice of a population crisis. Its Prime Minister has issued a dire warning, saying that the country is “on the brink of not being able to maintain social functions” due to the falling birth rate. Japan has one of the highest life expectancies in the world, which means that most will grow old and require care from others, but the workforce is shrinking as aren’t enough young people to fill the gaps in Japan’s stagnating economy.

Why is this? To use simple terms, Japanese people are having fewer babies. Women are postponing their marriages and rejecting traditional paths to focus on their professional lives, and the percentage of women who work in Japan is now higher than ever. However, there are also fewer opportunities for young people, especially men, in the country’s economy. Since men are still widely viewed as the breadwinners of the family, a lack of good jobs would also mean the men would avoid having children — and settling down — knowing they can’t afford it. With Japan’s high cost of living, it adds more reason for couples to steer clear of having a family.

The problem has only gotten worse since the Covid pandemic. In 2021, the birth rates in Japan declined to around 805,000 — a figure that was not expected until 2028. With much of the population choosing to focus on their careers instead, this number will only continue to fall.

In the early stages of the pandemic, there were jokes circulating that the lockdowns would cause another baby boom. However, the opposite came true. Japan experienced a reduction in birth rates, as well as other countries such as Taiwan and China — to an estimated 1.07 children per woman.

Japan’s population pyramid in October 2021. Kaj Tallungs. CC BY-SA 4.0

There are more and more elderly people in the country and not enough working-age adults to support them. The economy is at risk. But Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida promises to combat the low birth rate.

With Japan “standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society,” Kishida urges the national government to focus on policies regarding children and ramp up child-related programs, saying it “cannot wait and cannot be postponed.” He wants the government to double its spending on child-related programs and in April, he will launch a new Children and Families government agency to help in the endeavor.

This agency will unify policies across multiple government ministries to better deal with issues that concern children, such as declining birth rates, child poverty, and sex crimes. Kishida has plans to double the budget if necessary, without elaborating.

In the mid 1990s, the Japanese government launched a series of programs addressing their country’s low fertility, hoping to provide parenting assistance through increasing provision of childcare services and advocating for a better work-life balance. And in the 2010s, fertility policies were incorporated into Japan’s macroeconomic policy, national land planning, and regional and local planning.

Despite all these efforts, however, Japan’s goal to boost population remains unsuccessful. By forming the new agency, Kishida hopes these problems will be taken more seriously.

One thing remains clear, though — Japan is facing a population crisis. And if birth rates keep falling, the country’s economy will struggle under its effects.

Michelle Tian

Michelle is a senior at Boston University, majoring in journalism and minoring in philosophy. Her parents are first-generation immigrants from China, so her love for different cultures and traveling came naturally at a young age. After graduation, she hopes to continue sharing important messages through her work.

Why Japanese Fruit Is So Expensive

Japan places cultural importance on giving fruit gifts, leading to the cultivation of impressive fruits that can cost over $100

Read MoreMacaque Monkeys Attack in Yamaguchi, Japan

Macaque monkeys, previously peaceful residents of Yamaguchi, Japan, began targeted attacks in July.

Japanese macaque. Zweer de Bruin. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The city of Yamaguchi, Japan boasts historic temples, invaluable art, stunning gardens and macaque monkeys. Macaque monkeys have lived in highly populated areas of Japan since as early as the 1600’s, and up until recently, Japanese macaques have had very few concerning interactions with people.

However, since July 8th, more than fifty people in Yamaguchi have been attacked by the monkeys. City officials and experts say nothing like this has ever happened, and they even initially thought it was only one crazed monkey committing all of the attacks. But even after the monkey in question was euthanized, the attacks continued, leading the city to realize that an entire band of monkeys had inexplicably started attacking humans after years of peaceful coexisting. Fortunately, as of late July, no serious injuries have occured, but city officials have taken to tranquilizing threatening macaques, as they are not deterred by food or traps.

What makes these unprecedented attacks even more puzzling is the fact that they seem very coordinated, with an explicit goal, even if that goal is unclear to the people of Yamaguchi. While minor injuries have resulted from the attacks, some of the attacks appear to be attempted kidnappings. Additionally, the monkeys began by targeting primarily young children and older women. While over the past few weeks they have begun attacking adult men as well, these demographics are so specific that it begs the question: what is their intent? Unfortunately, no one knows yet.

A mother in Yamaguchi recalls a monkey having broken into her home, and attempting to drag her child away. She noted that the monkey tried to take the child with it. The monkeys have been entering homes, and even lurking outside of nursery schools. While there have been occasional macaque attacks in the past, they primarily live in harmony with humans, and a planned effort like this is unprecedented.

Two Japanese macaques. Etsuko Naka. CC BY 2.0.

In terms of the history of Japanese macaques, as noted they have lived in Japan since as early as the 17th century. They are also incredibly intelligent animals, making the decision of the Yamaguchi officials to euthanize one a difficult call. Macaques have opposable thumbs and even sometimes walk on two legs. They are known for doing very human-like activities, such as bathing and relaxing in groups in hot springs in Japan. This habit, as well as the habit of washing their food in the ocean, was learned behaviors within the group, and previously, scientists thought only humans passed traditions and behaviors through generations.

Despite the monkey attacks, which will hopefully come to an end soon, Yamaguchi has many sites to visit and a fascinating history. It is known for its temples, such as the Rurikoji Temple and Joeiji Temple. It is also a coastal town known for having high quality seafood and sake, which is perfect for travelers interested in food. Additionally, Yamaguchi is a very historic area, as the city contributed to the overthrow of the feudal era in Japan in the late 1800’s.

Tokoji Temple in Yamaguchi, Japan. Yoshitaka Ando. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Ultimately, Yamaguchi, Japan is a beautiful and historic city which is currently experiencing turmoil at the hands of macaque monkeys. Officials hope that the situation will be resolved soon, and once it is, consider adding Yamaguchi to your travel list.

Calliana Leff

Calliana is currently an undergraduate student at Boston University majoring in English and minoring in psychology. She is passionate about sustainability and traveling in an ethical and respectful way. She hopes to continue her writing career and see more of the world after she graduates.

3 Asian Theatrical Traditions

The cinema may be the world’s most prominent entertainment, but recorded film screenings cannot match the liveliness of performing theater. Learn about three theatrical traditions beloved by their Asian audiences for their craftsmanship and cultural significance.

Stage Theatre. AndyRobertsPhotos. CC BY 2.0.

Theater is a unique art in its ability to elicit both laughter and tears within the same showing. Throughout these three Asian nations the stage is a place where performers can bring imaginary worlds to life, or inspire their audiences to better their own.

1. Japan’s Rakugo

Rakugo. Isabelle + Stephanie Galley. CC BY 2.0.

Rakugo (fallen words) showcases a storyteller’s skill to enthrall their audience without the use of any costumes, scenery or special effects. Rakugo was developed during Japan’s Edo Period (1603-1868) by Buddhist priests who recounted dramatic tales to illustrate the impermanence of life and the sufferings elicited by materialistic attachment. Soon non-religious performers regaled crowds with parodied interpretations of those parables. A specialized sect of storytellers has emerged since, termed the rakugoka, who rely upon improvisation, exaggeration and, most critically, wordplay for their performances. A rakugoka presents upon the spartan kōza stage while dressed in traditional Japanese garb, and has only a sensu (paper fan) and a tenugui (hand towel) as props to aid them. With pantomime, voice and facial expressions the rakugoka will narrate one of 300 stories inspired by the realities of ordinary people.

The stories of rakugo are structured as back-and-forth dialogues between a set of archetypal characters and generally culminate in a funny climax. Popular character archetypes include cunning tricksters, miserly merchants, arrogant authorities and kaidan (ghosts or other apparitions). Each narration ends with an raku (fall), a humorous linguistic twist which serves as a punch line for the whole performance. Rakugo is analogous to a one-man show of sit-down comedy.

2. India’s Nukkad Natak

Nukkad Natak. DLF PUBLIC SCHOOL, INDIA. CC BY 2.0.

From universities to slums throughout India, nukkad natak (street drama) serves as a medium of entertainment as well as social commentary. India has a rich heritage of theater which traces back centuries, but nukkad natak was shaped very recently among the country’s schools and streets. In the 1980s, left-wing grassroots activists started to put on plays for the lay public to highlight major social and political issues. Nukkad natak grew especially popular among college students who identified an outlet through which they could express their unacknowledged emotions and views. Nukkad natak has since become a channel for communication and information among the uneducated masses.

Without any audiovisual equipment or cosmetic crew professionals nukkad natak troupes are forced to capitalize their bodies to the fullest. The troupers’ voices vary in pitch and volume as they undertake in constant physical motion. Troupes will not shy away from controversial scenes like sexual assault but will act them out publicly to provoke emotions. Some troupes dedicate their performances towards the portrayal of exemplary civic behavior. Even India’s private sector recognizes nukkad natak’s enormous influence on public society; some multinational corporations sponsor their own performances to advertise their products.

3. Indonesia’s Wayang Kulit

Yogyakarta, Wayang Kulit. Arian Zwegers. CC BY 2.0.

Although its origins are disputed to date, there is no debate as to the renown wayang kulit (shadow leather) holds today in Indonesia and neighboring countries. Intricately detailed leather puppets are deftly maneuvered by a dhalang (puppeteer) between a light source and a blank screen to portray a story via shadow. Performances feature plots derived from a bevy of sources, ranging from Hindu epics such as the Ramayana or Mahabharat to the East Javanaese Prince Panji cycle.

A show of wayang kulit may carry on through the night for eight hours and is usually accompanied by a gamelan bronze orchestra. A single performance may entail the use of hundreds of puppets, all of whom are designed with utmost faithfulness to visual symbolism. Puppets portraying noble heroes, for example, are crafted in accordance with the Javanese ideal of male beauty: slender build, long and pointed nose and eyes shaped like soya beans. A puppet’s colors represent characteristics; gold indicates dignity whereas white is the color of youth.

RELATED CONTENT:

Rohan A. Rastogi

Rohan is an engineering graduate from Brown University. He is passionate about both writing and travel, and strives to blend critical thinking with creative communication to better understand the places, problems, and people living throughout the world. Ultimately, he hopes to apply his love for learning and story-sharing skills to resolve challenges affecting justice, equity, and humanity.

Shohei Ohtani pitching in Sapporo. Scott Lin. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Baseball: A Japanese Pastime

America, over the years, has given a lot of cultural significance to the sport of baseball. We place it alongside apple pie and fireworks in the grand list of material symbols of our country. Not only that: baseball, over the years, has often reflected our country’s struggles back at us. It’s confronted discrimination in Jackie Robinson, and labor disputes with Curt Flood. It’s helped heal us, as well. Mike Piazza’s post-9/11 home run brought more joy to New York than anything that followed during the War on Terror.

But baseball is also of waning interest to many Americans. The sport is long, with games usually clocking in over three hours long. It also doesn’t market itself very well. Some of the greatest of all time are playing right now, but has any non-baseball fan heard of Mike Trout, Jacob DeGrom, or Shohei Ohtani? Likely not. The sport isn’t going away anytime soon, but there’s no doubt baseball’s cultural significance is declining in America. Fortunately, that isn’t the only place the sport is cherished.

Baseball was introduced to Japan during the late 1800s by way of an English professor from Maine named Horace Wilson. It didn’t take long for the sport to become a national pastime; professional leagues have existed since 1936, and the country’s national high school baseball championship, Summer Koshien, began in 1915. Today, baseball is Japan’s most popular sport; an almost bizarre outcome considering the existence of nationally-developed sports like sumo and globally adored sports like soccer.

But the popularity of baseball in Japan would be diminished if it weren’t for the homegrown players who have starred overseas. The first Japanese player to play in the MLB was a pitcher, Masanori “Mashi” Murakami, who debuted in 1964. Murakami wasn’t an elite player, and was even forced to return to Japan after two years due to his restrictive contract, but his appearance in the bigs opened the floodgates for others to make America’s game their own.

The first bona-fide Japanese star was pitcher Hideo Nomo. In 1995, Nomo’s first year in Major League Baseball, he posted a league-leading 11.1 strikeouts per nine innings to go alongside a 2.54 ERA (ERA stands for earned run average, or the average number of runs allowed every nine innings. Anything under 4 is considered good. Under 3? Great.) His rookie season is his best known (“Nomo fever” was said to have hit LA), but Nomo went on to have an excellent career, eventually retiring in 2008 after 323 games, 1918 strikeouts, and 2 no-hitters.

A fan holds a “Japan National Team” baseball flag at the World Baseball Classic. Steve Rhodes. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

There is also the case of Ichiro Suzuki, who with his illustrious career and unique style of play became one of the most well-loved baseball players of the 21st century. Ichiro had exceptional speed, stellar defense, and a superhuman ability to take care of his body, but he was best known for what he did with the bat in his hands. Ichiro’s approach was simple: he would slap the ball around the field, and beat out singles and doubles. He rarely walked or hit for power, but was so talented at this contact-oriented approach that it didn’t matter. It was primordial baseball planted firmly into the twenty-first century, and it worked. In 2004, Ichiro broke the single-season hit record, a record that had stood for 84 years and seemed all but unbreakable with how the game had changed. The principles of hitting have strayed from Ichiro’s even further since then; it’s not unlikely that Ichiro’s grand total of 262 hits in 2004 will stand until the earth is swallowed by the sun.

There’s only one active player who has a chance of topping Ichiro in the Japanese pantheon of stars, and his case is being made this very season. He’s a 27-year-old, currently having not just the best-ever season by a Japanese player, but possibly the best-ever season by anyone.

To explain Shohei Ohtani, one must first note that over its 150-year history professional baseball has become more and more a sport of specialization. Teams today might feature hitters who only hit against left-handed pitching, and speedsters who rarely start but are used late in games as pinch runners.

Ohtani is the one man who breaks up modern baseball’s prime order. He is a pitcher who hits; it’s as simple as that, really. Baseball players have long been separated into hitters and pitchers. Hitters don’t pitch (not seriously, anyway), and pitchers don’t hit (at least, not well; perhaps the best example of baseball’s specialist tendencies is how pitchers haven’t cared about being able to hit for a hundred years, despite the fact that half of the league still requires them to on a regular basis). But Ohtani plays both roles.

That in itself is historic. No player has been both a MLB pitcher and a lineup regular since Babe Ruth, who served the role in 1919. But here’s the kicker—Ohtani is really, really good at both his positions. He has hit 44 home runs while pitching to a 9-2 recond and a 3.36 ERA so far this season. Those are elite statistics, better than Ruth’s 1919 numbers. The value of one man bringing a season of premier pitching and hitting to his team is hard to quantify. But the case can be made that Ohtani’s 2021 season is the greatest of all time, at least so far. There’s no doubt the man is a one-in-a-million player, a gift from the baseball heavens. By coming from Japan, he also represents a nation that may lead in taking the sport forward.

This year, Japan beat the United States to win the gold medal in Olympic baseball. The victory, though marred by the fact that the best players from both countries stayed home, represented another step up the baseball ladder for Japan. As baseball exits America’s zeitgeist, it continues to grow in the island nation. The NPB’s level of play is going up—it’s still behind the major leagues, but not by a massive amount. Even more important is fan interest. In 2019, the last full season of the NPB, the league’s total attendance numbers grew to second in the world across all professional sports leagues.

As more stars are born and made, Japan’s baseball legacy will only continue to grow. Who knows? Maybe in a century, Japan will have come so far that baseball fans will diminish the careers of MLB stars like Trout, DeGrom, and Ohtani. They can’t be that good, the fans will say. They were playing in the United States.

Finn Hartnett

Finn grew up in New York City and is now a first-year at the University of Chicago. In addition to writing for CATALYST, he serves as a reporter for the Chicago Maroon. He spends his free time watching soccer and petting his cat.

Amid Pandemic, Japan Faces an Epidemic of Loneliness

Japan has a Minister of Loneliness to address skyrocketing rates of suicide and isolation, some stemming from COVID-19 among other reasons. The elderly and hikikomori, modern day hermits, seem most affected.

Read More5 Famous Japanese Flowers and Their Cultural Significance

Japan is home to many incredible feats of nature, but arguably one of the most beautiful parts of Japan’s landscape is its flowers—many of which can only be found in Japan.

Sakura and Mt. Fuji. Skyseeker. CC BY 2.0.

Flowers are national symbols of Japan. They represent specific emotions or sentiments and are often given as gifts to express unspoken feelings. In Japan, flowers communicate emotions in place of words; the Japanese “say it with flowers.” The Japanese proverb, “Iwanu ga hana 言わぬが花,” literally translates as “not speaking is the flower.” It means that some things are better left unsaid. This language of flowers is called “Hanakotoba,” with each flower conveying a very specific meaning and sentiment in Japanese culture. This tradition stems from Japan’s strong ties to Buddhism, which teaches the value of appreciating the present moment and connecting with nature. Below are five famous and culturally important Japanese flowers.

Lacecap Hydrangea. Ali Eminov. CC BY-NC 2.0.

1. Lacecap Hydrangea

Hydrangea macrophylla is a species of flower in the Hydrangeaceae family, native to Japan. There are many components to this plant, but they all come together to form one beautiful flower. The flowers are white and purple with four wide petals and small blue bulbs in the center—a feature of regular hydrangeas. In the middle of these flowers is a bunch of smaller blooms in shades of blue, purple and green. The flowers on the outside grow into large petals, while the bunch in the center remains as smaller flowers and buds. The Japanese name for this flower is Gaku, meaning “frame,” and representing the formation of the flower. In Hanakotoba, hydrangeas represent pride; this flower is gifted to someone the giver is proud of.

A red-veined cardiocrinum cordatum flower. Peganum. CC BY-SA 2.0.

2. Cardiocrinum cordatum

Cardiocrinum cordatum is a species of flowers in the lily family that is native to Japan and specific Russian islands. This flower resembles a lily, but its leaves are different in that they are shaped like a heart. The pale green flower blooms to the side, and is often used ornamentally due to its large, showy leaves. In Hanakotoba, white lilies represent purity and chastity.

Ranunculus japonicus flowers. Greg Peterson. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

3. Ranunculus japonicus

Also known as the Japanese Buttercup, this flower is a perennial from the family Ranunculaceae and is of Chinese and Japanese origin. Mainly growing in mountains and fields from Hokkaido to Okinawa, the Japanese Buttercup is an abundant, wild grass. In terms of appearance, these flowers are a bright yellow, with five rounded petals and a ring of yellow fringe around the small green bulbs in the center. According to the Japanese meaning, its leaves resemble horse hoofprints in the grass. Although very small, these flowers are bright and bring happiness to those who see them.

Japanese Apricot (Plum Blossom). Toshihiro Gamo. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

4. Prunus mume

Also known as Ume or Japanese apricot, these blossoms are from an East Asian and Southeast Asian tree species in the Armeniaca section of the genus Prunus (plums). They grow on the branches of the Japanese apricot tree and are incredibly fragrant with the smell of sweet honey. These flowers are also edible and make for stunning houseplants with their beautiful color and texture. The blossom’s buds are a dark pink, but they eventually bloom into a light pink when fully grown. In Japanese culture, this plant represents elegance, faithfulness and pure heart.

Camellia sasanqua, a November treat. Vicki DeLoach. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

5. Camellia sasanqua

Sasanqua is a species of Camellia native to both China and Japan, although it mostly grows in southern Shikoku, Kyushu and farther islands such as Okinawa. These bright pink and red flowers wilt one petal at a time, blooming from the end of autumn into the winter. In Hanakotoba, these flowers signify being in love or perishing with grace. Symbolizing the union between two lovers in the Chinese meaning, the delicate camellia petals represent the woman while the green leaves on the stem represent the man who protects her. The two components join together, even after death.

RELATED CONTENT:

VIDEO: Savor Japan’s Deep-Fried Maple Leaves

VIDEO: Bloom: Japan

VIDEO: Enter Kenya’s Rose Oasis

Isabelle Durso

Isabelle is an undergraduate student at Boston University currently on campus in Boston. She is double majoring in Journalism and Film & Television, and she is interested in being a travel writer and writing human-interest stories around the world. Isabelle loves to explore and experience new cultures, and she hopes to share other people's stories through her writing. In the future, she intends to keep writing journalistic articles as well as creative screenplays.

Ten Years After Nuclear Disaster, Recovery Remains Distant in Fukushima

The tsunami and ensuing meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant forced thousands to flee their homes. A decade later, some locals have returned home, but full recovery remains remote.

A tsunami’s wreckage. UCLAnewsroom. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Upon returning home after 10 years away, Masumi Kowata found a monkey in her living room. It wasn’t a joyful homecoming. In 2011, she evacuated her home along with 160,000 locals across Japan’s Fukushima prefecture. A cloud of radiation, spewing from three simultaneous meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, rendered swaths of land uninhabitable. Only in 2021 did the government allow she and her husband to return. Even then, it was only safe for them to visit for the day. Clad head to toe in plastic protective gear, she tread cautiously through the wreckage of an earthquake, a tsunami and neglect: a house shaken by earthquake, food left to rot for a decade, overgrown plants vining up the walls. The monkey had helped itself to Kowata’s belongings. It pranced around the room “wearing our clothes like the king of the house.”

A house under nature’s dominion. colincookman. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Wild animals have overtaken “difficult-to-return” zones, as the government termed them. Such areas encompass 2.4% of Fukushima prefecture and experience 50 times more radiation than what is considered safe. Boars, raccoon dogs and macaques roam the dangerously radioactive neighborhoods oblivious to the damage but unfettered by human life. They can cross streets without fear of speeding cars and feed on the produce of untended gardens, long overgrown. Human beings have returned much more slowly. Currently, the zones remain stuck in time at the moment of disaster.

The tsunami crashing through Minamisoma, Fukushima. Warren Antiola. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Agriculture struggles to recover as a result. Boars descended from the nearby mountains and invaded farms and rice paddies to feast on the crops. Hunters struggle to control the wild boar population. That is to say, they shoot as many as possible. “When I got married and was about to have my first child,” said one elderly boar hunter, “my mother said to me, ‘You’re going to be a father. Stop killing. Is that really the right thing to do?’ I stopped hunting then.” Now, he ventures out each day to beat back nature’s 10-year-long advance on Fukushima’s villages. “My town is abandoned and overrun with radiated boars,” he says. “It is my duty to help.”

The tasks of hunting down boars, tending to radioactive cattle and repopulating deserted towns fall to the few who have returned. Of the 160,000 who were evacuated after the meltdowns, only one-fourth plan to return. Most of them are elderly. The majority of evacuees found it easier to settle down elsewhere than endure a yearslong wait to return home. Young people especially favored big cities filled with jobs over their provincial hometowns, a trend that predated the disaster. In the nine years before the meltdowns, Fukushima’s population declined by 100,000. In the nine years after, it fell by another 180,000.

An elderly man with a picture of his late wife. Al-Jazeera English. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Local communities feel the absence of locals. As residents begin to plan for the future, they struggle to build a new community amid the ruins of an old one. Ancestral homes sit empty. Classrooms are frozen in time at the moment of the tsunami. Farmers spent generations breeding prized lines of livestock which are now useless. Radiated cattle, horses and pigs—as well as hunted boar—cannot be consumed because of radiated meat. Once famous for its produce, the prefecture’s fruits and vegetables now sell for below the national average. Though radiation tests ensure that the food is safe to eat, the stigma of nuclear disaster keeps customers away.

Hope Tourism seeks to make these ruins the foundation of the future. The group offers tours through areas that reflect both the devastation wrought by the nuclear disaster and the communal efforts toward reconstruction. Tourists see the abandoned elementary school in Ukedo, roads bent out of line by the tsunami’s rip current and black bags filled with radioactive soil. They can also tour villages trying to revive their local industries and meet community leaders who spread awareness about the dangers of nuclear fallout.

Where to put radioactive waste? UCLAnewsroom. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

In the face of hardship, locals still express pride in their roots. Iitate village joined the exclusive club of “most beautiful villages of Japan” in 2010, only to be wrecked by the tsunami and ensuing meltdowns. Ten years later, locals gathered to celebrate the opening of a new community center. It was built from parts of abandoned buildings: windows from old businesses, doors from run-down houses, a chalkboard from a school with no children to attend. An elderly woman in a green kimono sang folk tunes while the crowd enjoyed chestnut-filled rice balls. The Hope Tourism website states the village’s motto is a single word: madei. It means “thoughtfully” or “wholeheartedly” in the local dialect. It refers to the steady, persistent progress toward a revived community.

An abandoned building. Patrick Vierthaler. CC BY-NC 2.0.

The fight against nature’s invasion of Fukushima’s villages still preoccupies recently decontaminated zones. The national government branded the upcoming Olympics as the “Recovery Olympics” to highlight the region’s progress since the disaster. The Olympic torch relay will begin at Fukushima’s J-Village sports complex, which workers used as a base during the crisis in 2011. Japan will need to escape the shadow of the Fukushima disaster if the government is to accomplish key items on its agenda. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga pledged a carbon neutral Japan by 2050, an unthinkable prospect without nuclear power.

A radioactive bouquet. Abode of Chaos. CC BY 2.0.

National priorities rarely concern those repopulating Fukushima, though. They focus on the day-to-day resurrections of ghost towns. Some still search for ghosts. “I often tell people that my daughter would be a very independent and successful adult out in the world,” says one man. He lost his entire family in the tsunami, including his young daughter. “She was the type of girl other people could rely on.” With a shovel, a trowel and his gardening gloves, he digs through the soil for his daughter’s remains. “I’ve found about 20% of her, but 80% is still missing,” he says. “That means she’s definitely still here.”

Radiated livestock are marked with a white symbol that tells farmers the animal was affected by the 2011 meltdowns. There is no such symbol for the psychic wounds that Fukushima’s disaster continues to exact on its people.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

Two people walking with umbrellas in Kyoto, Japan. Andre Benz. Unsplash.

Japan Limits Reproductive Rights as Its Birth Rate Sinks

For many years, Japan has maintained one of the world’s lowest birth rates. This is only getting worse over time, as Japan recorded fewer than 1 million births and a population decline of 300,000 people for the first time in 2016. The blame for this loss often goes to women who prioritize their careers over bearing children, but in reality, economic insecurity may lie at the root of the problem.

Although Japan’s unemployment rate sits at only 3%, Jeff Kingston, a professor of history at Temple University’s Tokyo campus, claims that 40% of the workforce has unstable and temporary jobs “with low salaries and no benefits.” Such “irregular” workers have increased by about 7.6 million since 1995, whereas those with more stable jobs have decreased by 3.8 million. Such changes to the workforce stem from the revision of Japan’s labor laws in the 1990s, which allowed for a larger number of temporary employees in the country’s industries. The trend was further accentuated during the Great Recession, when there was high pressure on companies to decrease costs through the use of irregular workers.

Ryosuke Nishida, a sociology professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, elaborates on how even when men want to marry, their families often disapprove until a steady job is secured. Even if the woman has a stable position, roughly 70% of Japanese women quit their jobs after their first pregnancy and rely entirely on their husband’s salary. The issue doesn’t end there; employers tend to push their employees to the limit, since they are considered lucky to have found a full-time position.

To increase the country’s birth rate, Japan has begun to constrain women’s reproductive rights. Contraception is only available to women upon approval from a doctor and at the cost of $100. Moreover, as oral contraceptives were only legalized in 1999, knowledge of the pill is limited, causing emotional stress over its use and unknown side effects.

Although abortion is legal in Japan, many women resort to it because sexual counseling and education remain limited due to their taboo nature. Additionally, many health facilities across Japan require survivors of sexual assault to get consent from the perpetrator before getting an abortion, as the country’s Maternal Health Act requires approval from both a woman’s mother and her “spouse” to get an abortion. Many doctors perceive this to include the rapist, causing further pain for survivors. Although the government specifically excludes rapists, the prevalent sexism within Japanese society often leads such health care providers to neglect exceptions. The most significant issue is that despite frustrations around limited reproductive rights, women have little to no say in the matter due to the persistence of gender inequality in Japan.

Regardless, many women’s activists in Japan continue to fight for stronger rights and challenge those in high political positions to take further steps toward equality. To start overcoming its challenges, Japan must implement stronger counseling programs for women, pursue gender parity across all levels of society, and encourage men to openly address workplace stress.

Swati Agarwal

Swati is a sophomore at University of California, San Diego, where she is studying Environmental Sciences and Theatre. Although born in India, she was raised in Tokyo, which gave her the opportunity to interact with diverse people from distinct cultures. She is passionate about writing, and hopes to inspire others by spreading awareness about social justice issues and highlighting the uniqueness of the world.

Feline Fun: Japan’s Cat Culture and ‘Cat Islands’

It is always a pleasure to watch a cat prancing through the neighborhood or a skittish kitten darting for the bushes. But one country, Japan, has completely dissolved the line dividing feline and human interaction.

Cat cafe in Japan. nyxie. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Most people, if asked to name something from Japanese pop culture, would name the “Hello Kitty” cat cartoon as one of their top answers. As popular as the character has been with children across the world, a bustling cat scene exists within Japan itself entirely separate from Hello Kitty.

Japan’s residents hold a lengthy history of interaction with their feline friends. Cats were originally an invasive species introduced to Japan around 500 A.D. The creatures soon proved their worth by managing the islands’ rat population; the silkworm industry was being devastated by pesky rats, so the nation’s cats jumped into action. Over 1,000 years ago, wealthy members of Japanese society owned cats as pets. Evidence of cats in Japanese history can be found in literary works and paintings, many of which are hundreds of years old. The country’s oral history also contains many tales of worship for the cherished creatures.

Beyond being pets, cats in Japanese culture are an integral part of social interaction. “Cat cafes” have recently blossomed in Japan’s cat culture, allowing owners to mingle while their beloved friends wander among other felines.

While a stray cat is a common sight on any island of Japan, about a dozen islands have been dubbed the “Cat Islands” for their particularly dense population of felines. Two of the most popular are the islands of Aoshima and Enoshima:

Aoshima Island

Crowd of cats on Aoshima Island. 暇・カキコ. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Aoshima Island, located in southern Japan, boasts a human to cat ratio of 1-8. Cats were originally brought to the island to manage the rat population, but now they enjoy flashy media attention as internet sensations. The cats have become increasingly popular with visitors seeing viral videos, so an interactive feeding area has been installed. The cats have now become accustomed to interaction with strangers and will gladly show affection for a bit of food.

Enoshima Island

Cat on Enoshima Island. tokyofortwo. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Enoshima Island is a small island just over an hour south of Tokyo. The island’s human population is minuscule compared to the population of cats; there are only about 100 human residents among over 600 cats. The island draws many visitors for its Shinto shrines, which represent a religion that does not believe in the killing of cats. The island also houses a busy fishing industry, which has proven to provide plenty of nourishment for furry residents. Thus, the island’s cat population has bloomed.

Japan’s feline friends have embedded themselves in the nation’s history and culture, and their lofty position in society appears to be secure.

Ella Nguyen

Ella is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.