Smoking remains a serious health issue in the Pacific Islands region, with most nations having higher rates of cigarette smoking than the global average.

Read MoreFrom Famine to Frontlines: The Human Cost of Sudan’s Civil War

Sudan is facing what the U.N. has called the world’s largest humanitarian crisis as a result of its ongoing civil war.

Read MoreThe Cage Home Crisis in Hong Kong

Hong Kong's reputation as one of the most expensive housing markets in the world has led to more than 200,000 people living in cage homes, bedspace apartments likened to coffins for the living.

Read MoreAs Tehran Burns, Civilians are Caught in the Crossfire

Despite facing government censorship, the voices of Iranian residents reveal the fear and grief they endure under Israeli attacks.

Read MoreThe Impact of Authoritarianism on Food Insecurity in Chad

Food insecurity and the authoritarian regime in Chad have denied many individuals and communities access to fundamental human rights.

Read MoreThe Fight Against a Sinking City: Jakarta’s Sea Wall

Julia Kelley

While Indonesia’s government seeks to build a large sea wall to protect Jakarta from detrimental floods, criticism in the name of environmental and economic loss urges them to look for other solutions.

Flooding Ciliwung River in Jakarta Region. World Meteorological Organization. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

On the northwest coast of Indonesia stands Jakarta, the country’s capital and largest city. Sitting upon a low, flat alluvial plain with swampy areas, Jakarta is notably susceptible to major floods every few years from its multiple rivers and the adjoining Java Sea. This is made worse by excessive groundwater extraction and rising global sea levels, which have seen a worldwide mean increase of about eight to nine inches since 1880 due to global warming. Rapid urbanization, population growth and a change in land use have crowded more and more people into high-risk floodplain areas, leaving thousands displaced and large parts of the city submerged underwater during these natural disaster events. Although the Indonesian government built a coastal wall in 2002 to combat this, its collapse in a storm only five years later renewed the call for protective measures against destructive flooding. A new mega-project began in 2014, outlining both the construction of a new 29-mile-long sea wall and the so-called “Giant Sea Wall.” This “Giant Sea Wall,” a 20-mile-long artificial island shaped like a Garuda bird, Indonesia’s national symbol, will not only block storm surges but is also planned to contain homes, offices and recreational facilities.

This massive undertaking officially kicked off in February 2025 and is said by supporters to be key in dealing with the country’s land subsidence and flooding. Both President Prabowo Subianto and Minister of Infrastructure and Regional Development Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono claim that the project could save the government billions of dollars in disaster mitigation over the following 30 years. Despite this optimism, critics have come out against the large project, citing an array of detrimental economic and environmental issues that could result from construction. For example, many have noted how the proposed solution does not address the over-extraction of groundwater, which comes from excessive use by industrial and economic activities. In addition, the sea wall could disrupt marine biodiversity and, subsequently, the fishing industry, one of Indonesia’s strongest monetary sources. According to Maleh Dadi Segoro, a coalition of environmental and social groups, the sea wall would potentially narrow and close fishing catch areas, disrupting marine ecosystems and threatening the livelihoods of those who depend on them for food and income. Jakarta already faces low water quality in its rivers and canals, causing sewage and a lack of proper sanitation. Closing off Jakarta Bay for this sea wall, critics say, would turn the water into a “septic tank” or “black lagoon,” which necessitates a stronger water sanitation system immediately.

Controversy stirred up by the sea wall proposal has thus solicited alternative solutions. There has been an interest in using the water to its advantage, rather than working against it. This would entail diverting surplus waters, including that from floods, to surrounding farm areas where it could be stored. Restoration has also been widely proposed, as described by professor of oceanography Alan Koropitan for The Guardian: “If, instead, we can restore the bay and its polluted waters, that would mean something good for civilization in Indonesia.” Among all these suggested plans, environmental, social and economic protection are set at the center, urging the Indonesian government to rethink its monumental and costly plan.

GET INVOLVED:

Those looking to help support those affected by floods and flood prevention in Indonesia can do so by checking out relief organizations, such as The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies’ Disaster Response Emergency Fund, Peace Winds and Mercy Corps, all of which provide immediate and long-term support. Furthermore, individuals interested in combating sea level rise can look into taking actions that counter global warming, including using renewable energy, reducing greenhouse gas usage, considering electric vehicles, recycling, decreasing food waste, keeping the environment clean, or getting involved with local communities and government to organize plans and legislation.

Julia Kelley

Julia is a recent graduate from UC San Diego majoring in Sociocultural Anthropology with a minor in Art History. She is passionate about cultural studies and social justice, and one day hopes to obtain a postgraduate degree expanding on these subjects. In her free time, she enjoys reading, traveling, and spending time with her friends and family.

Cholera Outbreaks: Nigeria’s Struggle with a Reoccurring Epidemic

Julia Kelley

Poor access to clean water and underdeveloped facilities has led Nigeria to face a decades-long, deadly battle against cholera.

Access to Safe Water in Nigeria. EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

For decades, Nigeria has faced major cholera outbreaks throughout the country, posing a serious threat to public health. The disease, an acute diarrheal infection caused by ingesting food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, is a major indication of inequity, as well as a lack of social and economic development in the areas where it forms. Since 1972, cholera has plagued Nigeria in intermittent outbreaks that have claimed thousands of lives, the worst being in 1991, with a high of 59,478 reported cases and 7,654 deaths. Despite numerous attempts by the World Health Organization, the Nigeria Center for Disease Control and the Borno State Ministry of Health to provide support through free cholera vaccines and implement prevention and preparedness, the country continues to fight against large, destructive outbreaks.

Many factors make Nigeria especially prone to these widespread epidemics, including a lack of access to safe drinking water, a lack of infrastructure necessary for water supply and waste disposal and a lack of health facilities. Particularly in smaller communities and remote villages, sourcing clean water is a challenge that leads residents to dig their own wells. Moreover, during the dry season, these wells dry up and leave individuals only with the more hazardous alternative of shallow streams. Poor weather conditions worsen this significant obstacle to clean water and sanitation. Flooding, for example, increases food insecurity by destroying farmland, creating economic loss, demolishing sanitation facilities and contaminating sources of clean water. Several financial issues, including poor investment, funding allocation and low human capital, in conjunction with already deficient infrastructure and low community participation, also contribute to a lack of secure water infrastructure. Not only does this make for a higher potential of infection, but Nigera’s healthcare infrastructure is also underdeveloped, lacking the medical facilities and supplies necessary to treat those infected with cholera. Limited medical equipment and supplies, as well as a lack of internet connectivity, make it extremely difficult to heal patients and facilitate important reporting of cholera data.

These issues remain significant and continue to threaten the lives of Nigeria’s citizens. This is exemplified by the country’s most recent outbreak in 2024, which saw about 11,000 recorded cases and 359 deaths in October that year. Intense rains throughout the year led to widespread floods and dam breaks across Nigeria, weakening water infrastructure, destroying farmland and leaving many homeless in damaged areas, overall causing a large part of the country to be vulnerable to diseases like cholera. This most recent epidemic was met with policy and prevention program recommendations in the hope of impeding future spreads, the most critical of which being Water, Sanitation and Hygiene services. These accelerate and sustain access to safe water, sanitation services and good hygiene practices, all of which are the main deterrents of cholera spread. While this strategy proved effective when instituted by the Nigerian government during the 2018 outbreak, it still requires increased government funding and outside investment to remain effective. Public health and safety continue to endure disadvantages, as the threat of cholera looms over the country.

GET INVOLVED:

For those looking to get involved in supporting the fight against cholera outbreaks in Nigeria, check out organizations such as WaterAid, Bread and Water for Africa, Save the Children and The Water Project, groups focused on supplying safe drinking water and sanitation to Nigeria, as well as many other countries in Africa. In addition, organizations like Doctors Without Borders, the World Health Organization, ICAP Global Health and Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance provide medical support to cholera patients in Nigeria and contribute to the development of disease control and prevention.

Julia Kelley

Julia is a recent graduate from UC San Diego majoring in Sociocultural Anthropology with a minor in Art History. She is passionate about cultural studies and social justice, and one day hopes to obtain a postgraduate degree expanding on these subjects. In her free time, she enjoys reading, traveling, and spending time with her friends and family.

The History of Favelas, Brazil’s Impoverished Towns

Since their emergence in the 19th century, favelas have faced continuous struggles with poverty and crime, a symbol of the tension between Brazil’s government and its underrepresented communities.

Favela of Telegrafo. patano. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Scattered throughout Brazil are built-up communities known as favelas. These towns, principally found on the outskirts of large cities like Rio de Janeiro or Sao Paulo, are settlements marked by their unique urban development. While they are often associated with drugs, crime and poverty, these neighborhoods are a symbol of Brazil’s complex history.

Finding their origins in the late 19th century, favelas emerged amid a period of tumultuous political and social change in Brazil. They initially formed after the country abolished slavery in 1888. With a large number of impoverished former slaves left homeless and unemployed, they started forming temporary shelters. These were mainly squatter settlements near their work, which was often found in cities. Over the years, these communities grew in number and size. However, it was only after the Canudos War in 1898 when they became the large settlements we know today. The War on Canudos, a deadly civil war that saw a massacre in the small town of Canudos, left almost 20,000 ex-soldiers homeless after their return from the conflict. With nowhere to live, the group established the first favelas in the federal state of Bahia.

As Brazil’s class divide grew, more favelas popped up from the 1940s to the 1970s, becoming more organized with newly created residents’ associations serving as communicators between the towns and the government. Collaboration between the two led to agreements about water and electricity accessibility and construction investment, playing a large role in the favelas’ maintenance. However, rising politicians during this era also targeted the favelas for political gain, stereotyping their existence as slums breeding disease, illiteracy, crime and moral corruption. Many favelas were “removed” as a result, but other methods were sought out to build up and sustain the communities’ infrastructure. Despite various programs intending to improve buildings, Brazil’s economic crisis led to failed attempts at providing adequate housing in many areas. At the same time, cocaine markets were growing globally, and Brazil became a prominent drug producer and transit point between European and U.S. markets. These criminal groups formed during the 1980s and solidified in the early 2000s, attracting more police attention to the neighborhoods.

In 2022, about 8.1% of Brazil’s population lived in favelas. Because of their densely built-up infrastructure and continuous struggles with crime and drugs, favelas have also become synonymous with slum life. Widespread poverty, in particular, has grown to be favela residents’ largest struggle, with economic hardship producing limits on food, healthcare and education. The government has proposed various methods to help tackle these ongoing issues and support the overall conditions of these communities. Authorities have introduced programs to help residents: setting up training programs, providing low-interest loans or materials to construct accommodations and building facilities such as health clinics or schools. Despite these attempts, favela residents still lack full sociopolitical representation and face police violence. Thus, activism in favela communities remains imperative, as residents continue to search for peace and draw attention to the need for social development and increased rights.

GET INVOLVED:

Residents living in favelas struggle against police brutality, discrimination and stark poverty daily. Those looking to help address these issues can do so in several ways, including through making donations. Outreach organizations include: The Favela Foundation, focusing on the development of sustainable social and educational programs; Catalytic Communities, an NGO based in Rio de Janeiro bringing sustainable programs and legislative support to favelas; and The Gerando Falcões Fund of BrazilFoundation, bringing education and economic development to the favelas. Supporting favela locals in their fight to speak out against systemic violence is also very important. Using social media to follow, share and repost activism can help circulate news and reframe the stereotypes usually associated with favela communities.

Julia Kelley

Julia is a recent graduate from UC San Diego majoring in Sociocultural Anthropology with a minor in Art History. She is passionate about cultural studies and social justice, and one day hopes to obtain a postgraduate degree expanding on these subjects. In her free time, she enjoys reading, traveling, and spending time with her friends and family.

The Ethics of Poverty Tourism in Brazil’s Favelas

Understand the implications of poverty tourism in Brazil, what a favela is, and how the growing tourist rates raise concerns about safety.

Read MoreLong, Strange Trip: Psychedelic Drug Use and Legalization

With psychedelic drug reform still underway, research indicates that microdosing may be useful for medical and therapeutic treatment.

Capitol Records Cover. Daniel Yanes Arroyo on Flickr. CC BY-NC 2.0

In the 1960s, psychedelic drugs became central to counter cultural identity, as they were believed to expand human consciousness and helped inspire the era’s writing, art and music scene. Their acceptance only went so far, however, the war on drugs led to the ban of psychedelic drug use in 1968. These drugs include psilocybin mushrooms (magic mushrooms), MDMA (ecstasy, molly), and LSD (acid). But recent studies show that psilocybin may be used to treat alcohol and tobacco dependence, as well as mood disorders like anxiety, depression and OCD. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already declared psilocybin as a “breakthrough therapy,” with growing evidence for its efficacy in treating cases of depression that have proven resistant to psychotherapy and traditional antidepressants.

Psilocybin mushrooms. Mushroom Observer on Wikipedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0

Some argue that the legalization of psychedelic drugs would be positive, with regulated companies outcompeting the black market and manufacturing safer drugs (e.g., there would be little risk of products being laced with fentanyl). The status of drug policy reform varies across the U.S. Some states—including Washington, Texas and Connecticut—are actively studying the medical effects of psilocybin. In California, several cities, including Oakland, Santa Cruz, Arcata, Berkeley and San Francisco, have already passed resolutions to decriminalize the possession of psychedelic drugs, excluding peyote. The use of peyote in Native American ceremonies and sacraments is protected under the First Amendment of the Constitution as a form of Free Exercise of Religion. Despite this, the supply of Peyote is severely limited, to the point of being listed as vulnerable to extinction on the IUCN Red List. In several states, including New York, Florida and Utah, legislators have introduced bills to legalize psilocybin for clinical use that ultimately failed to pass. Psychedelic drugs remain illegal under the Controlled Substances Act at the federal level in the U.S.

Legislation varies even more worldwide, but many countries have less stringent laws than the United States. In Australia, MDMA and psilocybin may be prescribed for PTSD for depression. In the Bahamas and British Virgin Islands, psilocybin is legal to possess but not to sell. In Mexico, citizens cannot be prosecuted or charged if psilocybin is used for spiritual or religious purposes. Most of Europe has either decriminalized or deregulated aspects of the use or trade of psychedelic drugs, including countries like Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. The definition of “decriminalization” varies, but usually implies that one can possess a certain amount of a substance avoiding fines or other penalties, despite it being illegal.

While concerns regarding the safety of psychedelic drugs are and will continue to be raised, statistics show that emergency room visits related to psilocybin and LSD are infrequent. Legalizing psychedelic drugs would signify for advocates a stride toward personal autonomy, enabling individuals to make informed choices about what they put in their bodies. This shift mirrors a growing global interest in investigating the therapeutic and medical potential of psilocybin, prompting a reevaluation of 20th century policies.

Agnes Moser Volland

Agnes is a student at UC Berkeley majoring in Interdisciplinary Studies and minoring in Creative Writing, with a research focus on road trip culture in America. She currently writes for BARE Magazine and Caravan Travel & Style Magazine. She is working on a novel that follows two sisters as they road trip down Highway 40, from California to Oklahoma. In the future, she hopes to pursue a career in journalism, publishing, or research.

Afghanistan is Starving: The Ongoing Food Crisis Under Taliban Rule

Millions of Afghan children will suffer crisis-level hunger by the end of 2024.

Arid landscape in Afghanistan. Unsplash. CC0

Afghanistan has had no shortage of crises so far this year. Frequent flooding in the north and west in May and severe drought in January have triggered a monumental inflow of humanitarian aid, but despite the world’s best efforts, it appears that the fallout from these events will be seriously damaging for the already impoverished and oppressed citizens for the rest of the year.

Studies by Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, an independent global hunger monitoring organization, suggest that around 12.4 million Afghan citizens will be faced with food insecurity between June and October of 2024. Of those affected, just over half are children. In addition, 2.4 million citizens will experience starvation at emergency levels; this categorization is just above outright famine.

A variety of causes have been listed for the crisis. Back in May, flooding devastated many northern towns, affecting 60,000 citizens and reducing farmland to fields of mud. Based on weather patterns, these floods are expected to continue throughout the year, preventing any recovery of the farmland and causing a major decrease in domestic food production.

Additionally, an unexpectedly warm and dry winter has led to a lasting drought across the southern and western parts of the country. Although rainfall has increased somewhat in recent months, the arrival of the La Nina weather pattern in the fall is expected to bring even more dry, warm days. Although some farmland is recovering thanks to the brief respite provided by El Nino, much of the land is about to be confronted with a second round of drought conditions, further cutting down food production.

The most prominent cause of food insecurity, however, is the ever-present and ever-controversial Taliban government. Local currency has taken an alarming plunge while food prices, thanks to scarcity caused by the aforementioned environmental catastrophes, continue to soar. The Taliban’s apparent lack of concern for Afghanistan’s economy suggests that there will be no serious action towards rectifying the crash. Economic aid from foreign countries helps somewhat to avert the biggest fallout from the crisis, but the problem is virtually unfixable without changes in the regime's policies.

Regardless of how it began, the food crisis in Afghanistan is only getting worse—and fast. The country is alarmingly unequipped to pull itself out of poverty and hunger; action by charities and foreign governments is helping, but more is needed to prevent the looming threat of starvation. Hundreds of thousands of families are actively struggling to find their next meals, and millions of children will soon be forced to endure near-famine levels of food insecurity.

How You Can Help

Organizations such as the World Food Programme and UN Crisis Relief are actively supplying food to communities most impacted by the crisis. Estimates show that around $600 million are needed to ease the burden across the entire country. Other groups, such as UNICEF, are specifically aiming to feed and protect the millions of starving children and their families. There is no way to fix Afghanistan’s economic and political crises from the outside, but these organizations have already helped to feed and house countless citizens facing down these disasters head-on.

Ryan Livingston

Ryan is a senior at The College of New Jersey, majoring in English and minoring in marketing. Since a young age, Ryan has been passionate about human rights and environmental action and uses his writing to educate wherever he can. He hopes to pursue a career in professional writing and spread his message even further.

Paradise for Tourists is Hell for Canary Islands Residents

Canary Islands residents are protesting against mass tourism, which they say is making the islands uninhabitable.

A crowded beach in Las Palmas. Trygve Bølstad. CC BY-NC-SA

The Canary Islands have long been a hotspot for tourism. Vacationers flock to the archipelago in imposing numbers, drawn by the islands’ mild climate, rich cultural history and stunning vistas. In 2023, approximately 14 million international tourists visited the Canary Islands, representing an increase of roughly 13 percent compared to the previous year, and tourism accounts for approximately 35 percent of the islands’ GDP. Unfortunately, not all residents are experiencing the benefits of this influx. In fact, many locals have begun to complain that the massive waves of tourism are actively contributing to a decline in their quality of life.

While the Canary Islands host large numbers of tourists every year, approximately 15 million, they are home to only 2.2 million native residents. Of those 2.2 million, 33.8 percent are at risk of poverty according to a living conditions survey conducted by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística of Spain in 2023. The same survey designated the Canary Islands as one of the autonomous communities in Spain with the highest percentage of people making ends meet with “a lot of difficulty.”

Canary Islands. PxHere. CC0 1.0

The tourism industry only exasperates the economic challenges faced by residents. The islands’ resources are simply not equipped to sustain the large numbers of tourists, who put pressure on health services, waste management, water supplies and biodiversity. According to reports, tourists use up to six times more water than residents who, as a result of a drought brought on by climate change and rising temperatures, have been subjected to restrictions on water usage. Meanwhile, tourist resorts and golf courses have not been made to comply with the same restrictions.

Biologist Anne Striewe commented on the toll tourism takes on the environment. “There are hundreds of boats and jet skis in our waters every day pumping petrol into the water,” she said, “then there are the boat parties which blast music all day long…this is picked up by whales and other creatures and really confuses and frightens them … Meanwhile, there have been multiple cases of animals being injured or killed by boat propellers, there are often vessels in protected waters but no one is cracking down on the activity.” According to the environmental group Salvar Tenerife (Save Tenerife, the largest of the Canaries), millions of liters of sewage water are being dumped into the sea off Tenerife and other islands every single day, with amounts rising in accordance with the number of visitors.

Sticker against overtourism, 2024. Rasande Tyskar. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Female residents have reported feeling unsafe in the presence of tourists who harass and follow them in public. Trailers park illegally and leave trash in their wake. The number of hotels being built and the amount of housing being converted to short-term rentals to accommodate these tourists has caused a rise in the cost of living. As a result, some locals have been forced to begin sleeping in their cars and in caves. "It is absurd to have a system where so much money is in the hands of a very few extremely powerful groups, and is then funneled away from the Canary Islands," says Sharon Backhouse, who owns GeoTenerife along with her Canarian husband, a program that runs science field trips and training camps in the Canary Islands and conducts research into sustainable tourism.

Thousands of locals took to the streets in April to protest over tourism and defend their right to live in their native land. “We are not against tourism,” Rosario Correo, one of the protesters, clarified to the media, “We’re asking that they change this model that allows for unlimited growth of tourism.”

Protesters are calling for a halt to the construction of a hotel and a beach resort on one of the few remaining unoccupied beaches, a moratorium on all tourism development projects, stricter regulation on property sales to foreigners and a more sustainable model of tourism that will not put the environment or the livelihoods of locals at risk. “I feel like a foreigner here, I don't feel comfortable anymore, it's like everything is made for British and German tourists who just want to drink cheap beer, lay in the sun and eat burgers and chips,” another protester, Vicky Colomer, said. “We need higher quality tourists who actually want to experience our culture and food and respect our nature.”

The protests have motivated the government to introduce measures to limit tourism. The island of Tenerife announced a tourist tax of an undisclosed amount that will go into effect on January 1, 2025 for tourists seeking to visit natural beauty spots. A law that would place harsher regulations on short-term rentals is also expected to pass in 2025.

Rebecca Pitcairn

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Uncontrolled Burn: Canada’s Devastating Wildfires

Thousands of wildfires, miles of scorched forests and colossal plumes of smoke are threatening Canada on all fronts.

Forest fire at night. U.S. Forest Service, public domain

Canada is no stranger to wildfires. According to the Canadian National Fire Database, over 8,000 fires occur every year, burning over 2 million hectares of land. The highest risk period for fires starts in April or May and lasts all the way through September or October, with hold-over fires potentially burning well into winter.

But recently, fires have become more and more frequent earlier in the year. These early fires have also been growing in severity and damage, which should only happen well into the summer. Canada has endured over a thousand fires in 2024 alone, with 104 currently raging as of late May. Most are relatively under control thanks to quick responses from fire teams, but about a seventh are registered as “uncontrolled.” Despite the best efforts of local fire companies and government action, these fires have devoured thousands of hectares of land and are currently threatening several cities across the country.

The Parker Lake fire, named for its apparent origin point, caused thousands of citizens of Fort Nelson in British Columbia to flee their homes. At that time the fire was already roughly 3 square miles in size; the long period of dry weather, coupled with strong winds, caused the fire to grow out of control, which prompted evacuation orders on May 11th. Parts of Alberta have also been given orders to prepare for evacuation as other fires steadily approach.

In addition to the threat posed by the blazes themselves, the smoke produced by the constant burning has blanketed most of Canada and is beginning to drift south into the midwestern United States. This smoke can cause serious reactions in those with existing respiratory illnesses and even be harmful to the lungs of healthy individuals. Given the severity of 2023’s wildfire season, we can expect a tremendous amount of smoke this year as well.

There are many possible causes for wildfires, ranging from the carelessness of individual hikers or campers to the climate itself. Higher global temperatures can cause more frequent flare-ups, long-lasting droughts can leave forest floors incredibly dry and flammable, and warmer winters leave less snow behind, resulting in even dryer conditions. Additionally, zombie fires—blazes that have smoldered underneath the snow over winter only to reemerge after the spring thaw—have increased the number of threatened communities.

How You Can Help

Fire season has only just begun in Canada and the nation is already being battered from all sides. Conditions are only expected to worsen as the temperatures rise and droughts linger; more evacuations are also expected as a result. However, several charities have already begun donating to the firefighters working to combat the blazes, as well as the many displaced citizens. Sites such as Global Giving and the Canadian Red Cross are excellent ways to help offset the devastation wreaked by the hundreds of wildfires.

Ryan Livingtston

Ryan is a senior at The College of New Jersey, majoring in English and minoring in marketing. Since a young age, Ryan has been passionate about human rights and environmental action and uses his writing to educate wherever he can. He hopes to pursue a career in professional writing and spread his message even further.

Madagascar’s Cyclone Gamane—The Devastating Storm Nobody’s Talking About

Thousands of homes were destroyed and families displaced, with almost no American news coverage.

Cyclone Gamane over Madagascar. NASA, CC0

A few weeks ago, Cyclone Gamane made landfall on Madagascar. It devastated the island in no time flat, leaving tens of thousands of people homeless and without food or electricity. It arrived on March 27th; the government declared a state of emergency on April 3rd. And despite all of this, there was almost no American news coverage about the disaster.

Gamane began as a tropical cyclone over the South Indian Ocean. By the time it reached Madagascar, its wind speed was clocked at an average of 93 mph, with gusts up to 130 mph recorded. Thirty-three communes were flooded in the three days it pummeled the northern coast, and more than 780 houses were destroyed. Eighteen people were killed and more than 22,000 were displaced from their homes. Estimates suggest that there are roughly 220,000 people in need of humanitarian assistance on the island.

Even before the cyclone, Madagascar was numbered among the worst off in the Global Hunger Index in 2023. Before the flooding in February and with Gamane, much of the island was unable to produce enough food to support the population. Roughly 1.6 million citizens are food insecure, relying instead on humanitarian aid. Additionally, the cyclone came at the beginning of Madagascar’s notoriously dry lean season, which lasts from late March until May. If conditions don’t improve quickly, there are concerns that large chunks of the country will experience crisis-level food insecurity.

Emergency supplies on the island are already low—Gamane is only the third crisis to hit Madagascar in 2024, after the Alvaro storm in January and heavy flooding in February. Local humanitarian associations have made efforts to help the populace recover, but without resources, the government has had to call for aid from other countries.

The UN has set up a funding program under the CERF, the Central Emergency Response Fund, to accumulate funds to send to Madagascar. As of April 21st, the program is 20% funded, and is seeking to raise 90 million dollars. Smaller humanitarian organizations, such as the Redemptorist Solidarity Office (headquartered in Cork, Ireland), have taken action in the meantime to provide what help they can. According to their website, the RSO has provided 15,000 pounds for financial support and is shipping several tons of food items and medical kits. They hope to raise enough money to help provide shelter-building supplies for the displaced as well.

Madagascar is uniquely situated as one of the most susceptible places on Earth to natural disasters. Over the last 35 years, more than 50 hazards, including locust swarms, droughts, and heavy flooding, have struck the country and affected nearly half of the entire population. This has, to some degree, resulted in less coverage being dedicated to each event; even now, almost a month since the storm first made landfall, it has received very little publicity in the United States. But despite this lack of interest, humanitarian action is still being taken. It will be an uphill battle, between the fallout from the storm and the height of the lean season approaching, but with the help of the UN and other independent aid groups, Madagascar can and will recover.

Get Involved

At the moment, due to the lack of publicity that the crisis has received in the US, there are not many volunteer opportunities within the country. Those looking to help can donate to SEED Madagascar (which seeks to combat food insecurity), UNICEF Madagascar (which is working to minimize the effects of climate change on the island), or the World Food Programme’s Madagascar mission (which aims to supply over 1.6 million people with humanitarian assistance).

Ryan Livingston

Ryan is a senior at The College of New Jersey, majoring in English and minoring in marketing. Since a young age, Ryan has been passionate about human rights and environmental action and uses his writing to educate wherever he can. He hopes to pursue a career in professional writing and spread his message even further.

Beyond the Quakes: Taiwan’s Earthquake Preparedness

Despite being hit with a 7.4 magnitude earthquake during rush hour on April 3rd, 2024, Taiwan has emerged largely unscathed. Why is that?

A seismogram of the April 3rd, 2024 earthquake in Taiwan. James St. John. CC BY 2.0

On April 3rd, 2024, the strongest earthquake in about 25 years rocked the streets in and around Hualien on the east coast of Taiwan, followed by hundreds of aftershocks. While the search for survivors remains underway, so far 13 people have been found dead, and nearly 1,000 people have reported injuries. While any number of deaths and injuries is tragic, these figures are minuscule compared to the near 2,500 dead and 100,000 injured during the 7.7 magnitude earthquake that struck in 1999 and left approximately 50,000 homes destroyed.

Considering its location along the Ring of Fire and the presence of three seismic belts in the country, Taiwan has a long history of earth-shaking events. The Ring of Fire refers to a fault line around the Pacific Ocean that is home to a majority of the world’s earthquakes. Because of this, Taiwan records an average of about 2,200 earthquakes every year, with a record of nearly 50,000 during 1999. Taiwan’s mountains then amplify the impact of earthquakes, which resulted in the landslides that accounted for most of the deaths on April 3rd.

Because of this susceptibility and catastrophic earthquakes in the past, Taiwan has developed some of the best earthquake preparedness techniques in the world. Following the devastating Chi-Chi earthquake in 1999, the Taiwanese government began reforming construction regulations. This included seismic retrofitting in buildings and infrastructure across the country and the prosecution of inadequate construction practices. Years of experience have also resulted in efficient emergency response, aided by surveillance cameras and social media used to identify locations requiring aid.

Educating the public has been another initiative to prevent deaths during earthquakes and aftershocks. In addition to public awareness campaigns, the Central Weather Administration frequently publishes resources including information and tips surrounding earthquake preparedness. The Central Weather Administration has also run a real-time seismic network since 1994, which tracks data and notifies the public of seismic activity through an early warning system. The data collected by the seismic network is also used to update building codes.

GET INVOLVED

Ways for people to support Taiwan’s emergency response and earthquake preparedness include donating to and supporting organizations such as the Red Cross, Taiwan Root Medical Peace Corps and Peace Winds America.

Madison Paulus

Madison is a student at George Washington University studying international affairs, journalism, mass communication, and Arabic. Born and raised in Seattle, Washington, Madison grew up in a creative, open-minded environment. With passions for human rights and social justice, Madison uses her writing skills to educate and advocate. In the future, Madison hopes to pursue a career in science communication or travel journalism.

The Global Social Ladder: The Best and Worst Countries for Social Mobility

The World Economic Forum's Global Social Mobility Report 2020 unfolds a gripping narrative.

Read More5 Historical Epidemics that Changed the World

Disease outbreaks are inherent to a populous, globalized world.

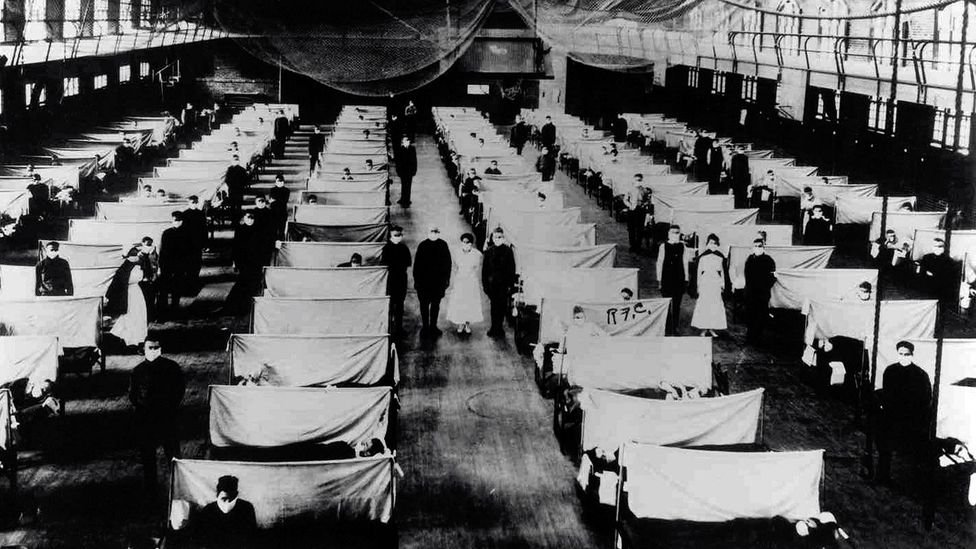

Doctors and nurses in biohazard suits during the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic. National Museum of Health and Medicine. CC0.

Pandemics have been a part of the human story since the agricultural revolution in 10,000 BC. Agriculture gave people the ability to create more food than they ever had before, which meant that the human population soared. People began packing together and settling down in large communities without modern sanitation, creating the ideal conditions for the spread of disease. As time went on, larger and larger communities established extensive trading networks with the ability to spread disease across continents.

With each disease outbreak, humanity has developed better defenses and practices to help prevent catastrophic losses. However, as long as population sizes continue to rise and the global community becomes ever more interconnected, worldwide pandemics will always be something that humanity must contend with.

This trend towards an increasingly populous and interconnected world is what fueled the global sweep of the COVID-19 pandemic. As Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security said, “Viruses used to spread at the speed of a steamboat. Now, they can spread at the speed of a jet. In that sense, we’re more at risk.” The only way to adapt to the expanding threat of disease is to learn from the past and prepare for the trends of the future. Below is a list of some of the most devastating pandemics in history and how humanity’s response to disease changed because of them.

1. The Bubonic Plague

14th Century CE

The plague of Florence, 1348. Boccacio’s Decam Wellcome. CC-BY-4.0.

Also known as the Black Death, the Bubonic Plague is the most notorious pandemic in history. It is believed to have killed between 30–50% of the European population in the 14th century, anywhere between 75 million and 200 million people. The Bubonic Plague is also thought to have killed 25 million people in Asia and Northern Africa at the time. The Black Death is known to have an incredibly high mortality rate, killing between 30-100% of those afflicted depending on the manner of infection.

The Bubonic Plague spread globally as a result of the Silk Road, which connected the world through trade networks. Rodents carrying fleas infected with the plague were easy stow-aways in trading caravans and vessels. This is one of the first instances where globalization caused a deadly, widespread disease outbreak.

At the time, the Black Death was thought to be the result of a combination of bad air, an imbalance in the body’s fluids or “humors,” and the wrath of God. Treatments included potions, fumigations, bloodletting, pastes, animal cures and religious cures. Persecution of minority groups was also common, particularly the Jewish population, who became a scapegoat for the suffering caused by the plague. Despite the outlandish and sometimes brutal practices of the 14th century, one method developed in the wake of the Black Death has proved incredibly effective: quarantine. Though, like today, many medieval citizens did not abide by quarantine practices, implementation of — to use a contemporary term — social distancing was one of the few effective practices to slow the spread of the Bubonic Plague.

2. Tuberculosis

7,000 BC – present day

A sick woman lies on a balcony with death standing over her, representing tuberculosis. Richard Tennant Cooper. CC-BY-4.0.

The sheer scope of tuberculosis in human history is almost difficult to fathom. Tuberculosis in humans can be traced back 9,000 years to Atlit Yam, a city now under the Mediterranean Sea, where archeologists found the disease in the bodies of a mother and child buried together. Tuberculosis, which has gone by many names throughout time, including “the white death” in the 1700s and “consumption” in the 1800s, is one of humanity’s great enemies. According to the CDC, from the 1600s–1800s, Tuberculosis was responsible for 25% of all deaths.

Today, vaccines and antibiotics are available to prevent and treat tuberculosis. These developments in tuberculosis treatments saved 74 million lives between 2000 and 2021. However, despite this breakthrough in modern medicine, a total of 1.6 million people died from tuberculosis in 2021 according to the World Health Organization. Over 80% of these deaths come from low and middle income countries. Modern medicine means that Tuberculosis is treatable, but these treatments are not universally accessible. In a globalized world, access to healthcare cannot be a first world luxury if outbreaks are to be prevented.

3. The Columbian Exchange

1492–1800 CE

Spanish imperialists conquer the Americas. Wilfredor. CC-BY-SA.

The Columbian Exchange is a massive interchange of people, animals, plants, and diseases that took place between Eastern and Western Hemispheres after Columbus’ arrival in the Americas in 1492. This process introduced a number of foreign diseases that Native Americans had no immunity to, whose toll reached genocidal proportions, killing between 80–95% of Indigenous Americans within 100–150 years of Columbus’ first landing. Some of the diseases that plagued the Native Americans include smallpox, measles, influenza, chickenpox, the bubonic plague, typhus, scarlet fever, pneumonia and malaria. European imperialism is to blame for the catastrophic spread of disease to the Indigenous population.

4. The Spanish Flu

1918–1919 CE

Infected patients were isolated during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. Jim Forest. CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0.

After WWI, global contact and poor sanitary conditions during the war caused a worldwide outbreak of the H1N1 influenza virus, known at the time as the Spanish Flu. 500 million people were infected, one third of the world’s population at the time. Of those infected, 50 million people died worldwide, including 675,000 people in the United States.

This pandemic led to a number of medical innovations still in use today. One of which is the widespread use of masks to prevent the spread of disease. The Spanish Flu pandemic also led to innovations in vaccine technology and spurred our understanding of genes and the chemicals that encode them.

5. AIDS Epidemic

1981-1990s

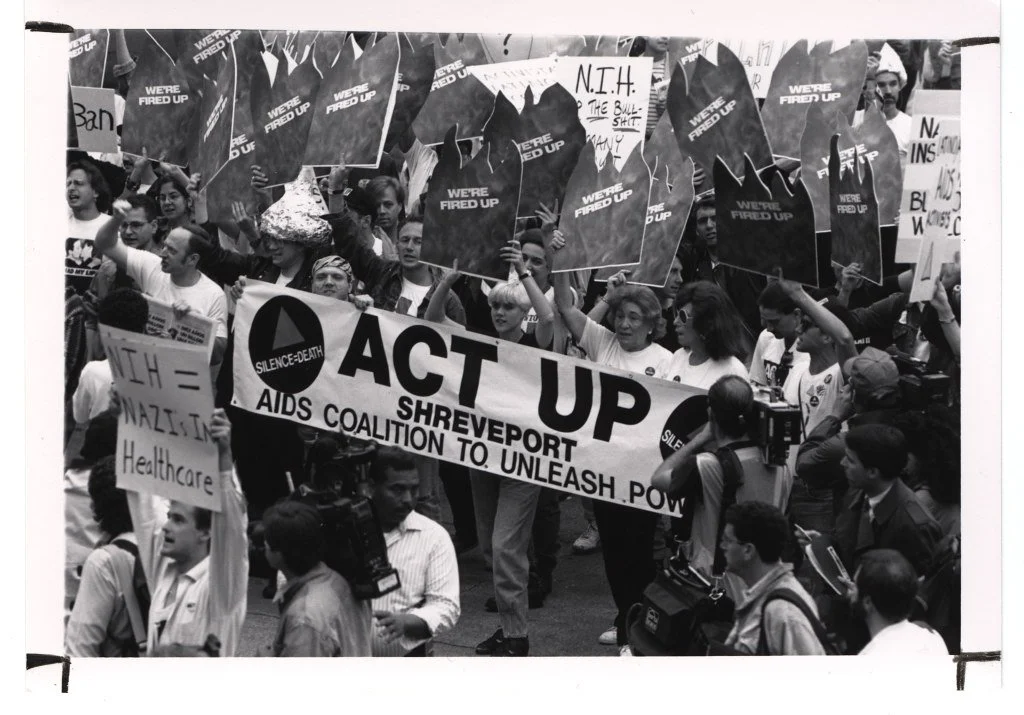

Protestors march against the stigma caused by the AIDs epidemic. NIH History Office. CC0.

HIV originally jumped from chimpanzees to humans in the early ‘80s, most likely due to human hunters coming into contact with chimpanzee blood. As a result, 84 million people have been infected globally and 40 million people have died. The AIDS epidemic is notorious for the resulting stigmatization of the LGBTQ+ community, which were greatly, though not uniquely, affected by the disease. Epidemics throughout history, since the Bubonic Plague, have caused hysteria and scapegoating, a flaw in human nature that must be quelled.

Since the 1980s incredible strides have been made in the treatment of HIV and AIDS. As of 2021, 38.4 million people were living with HIV without it progressing to AIDS (when deadly symptoms appear) due to modern treatments. The treatment for HIV is taking daily antiretroviral therapy (ART), which is a cocktail of different HIV medicines. This treatment can allow people to live with HIV for decades without it progressing to AIDS.

Sophia Larson

Sophia Larson is a recent graduate of Barnard College at Columbia University. She previously worked as the Assistant Editor on the 2021 book Young People of the Pandemic. She has also participated as a writer and editor at several student news publications, including “The UMass Daily Collegian” and “Bwog, Columbia Student News.”

10 Natural Disasters that Shook History

Witness the awe-inspiring forces of nature unleashed through devastating hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and catastrophic floods.

Read MoreHow Malaria Might Make a Comeback in the US

In order to prevent another pandemic so soon after the last one, US authorities need to stop this new malaria outbreak in its tracks.

The female Anopheles mosquito plays host to the disease’s parasite. CC BY-SA 2.0

Over the past two months, seven cases of locally acquired malaria have been identified in the US. These cases, six of which appeared in Florida and one in Texas, have drawn significant attention as the first time in 20 years the disease has been transmitted domestically. At present, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported that all five patients have received medical treatment and are recovering positively, and that the risk of malaria reappearing in a more widespread epidemic across the U.S. is extremely low. That being said, this is a good reminder for those in charge of American public health infrastructure to reflect on how best to shore up national defenses, especially in the wake of the recent Covid-19 pandemic.

Malaria is caused by parasites, which commonly infect Anopheles mosquitoes, and who in turn transfer the disease to humans when they inject their proboscises into our bloodstreams. There are several species of the malaria parasite, collectively known as Plasmodium, some of which cause more serious cases than others, but all of which require tropical climates to thrive. Regardless of the species, malaria is still extremely serious and symptoms such as high fevers, chills, and nausea begin to manifest in a few weeks. Most worryingly is that malaria, if left untreated, is fatal. As of 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) believed that a grand total of 247 million cases of malaria occurred around the world, of which 619,000 were fatal. The majority of these deaths were children in various countries in Africa, where malaria is a constant present threat and contributes to a vicious cycle of social and economic poverty, taking a massive toll on countries in already precarious situations.

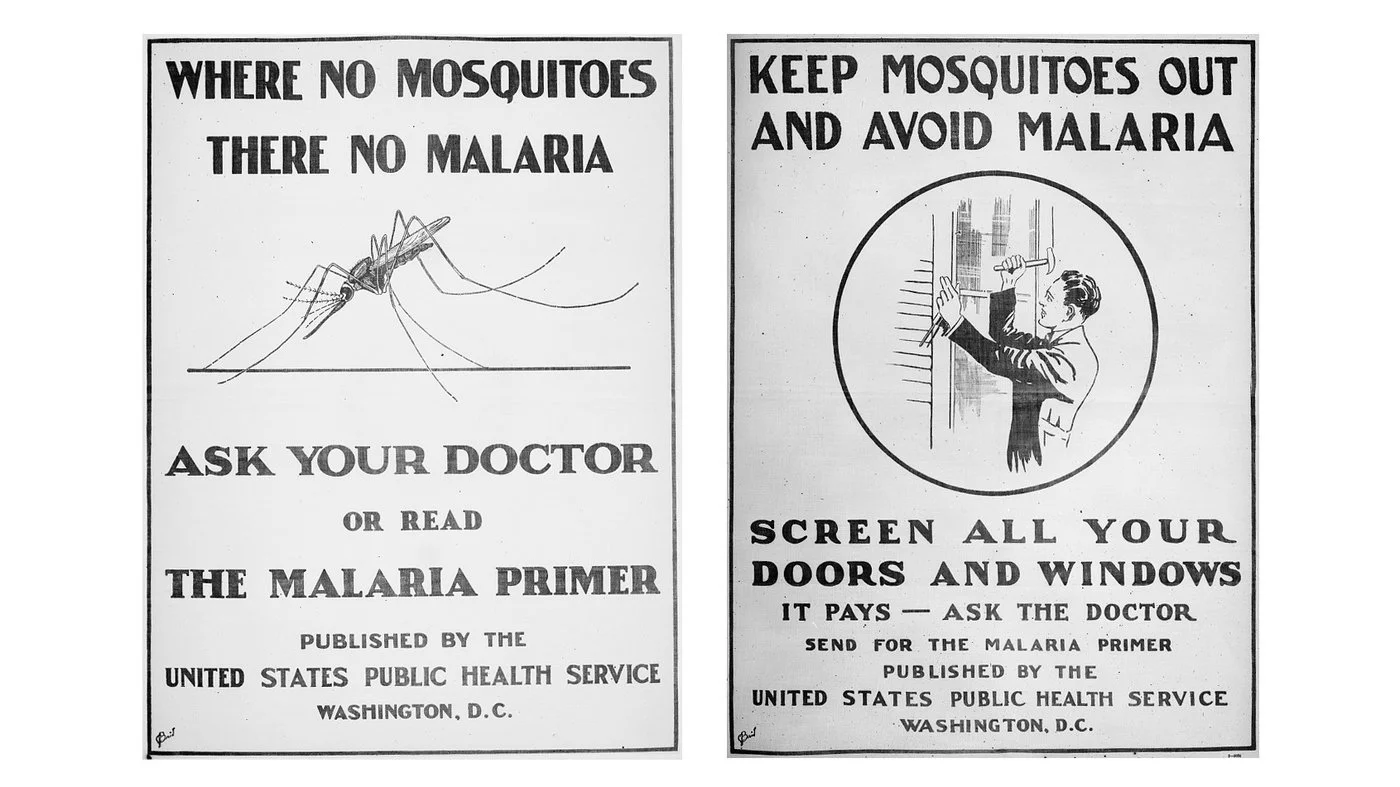

Malaria awareness in the US during the 1950s. Library of Congress. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

At the beginning of the 20th century, malaria was considered an extremely serious issue in the US; the CDC was actually founded in 1946 to eliminate the disease. Over the next six years, various public health measures such as insecticide use and window screens were implemented to reduce the 15,000 cases reported in 1947, and in 1951, the CDC finally announced that malaria was in the US no longer. This remained the case for decades, until an incident in 2003 when eight locally acquired cases in Palm Beach, Florida were identified. Fortunately, the outbreak was quickly quashed thanks to an immediate response campaign that completely rid the area of mosquitoes to prevent transmission. Since then, malaria has remained fairly absent from the American healthcare landscape.

It is important to note, however, that malaria has never been completely extinct in the US; prior to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, roughly 2,000 cases of the disease were identified and reported annually in patients who had traveled to countries with high incidences of malaria in Southeast Asia and Africa. Additionally, once infected individuals return to the US, local mosquitos who feed on them can pick up the parasite and spread it further. Every so often, this may result in a small reintroduction of the disease and potentially even some limited transmission, but there has never been any worry of it resulting in a much widespread epidemic.

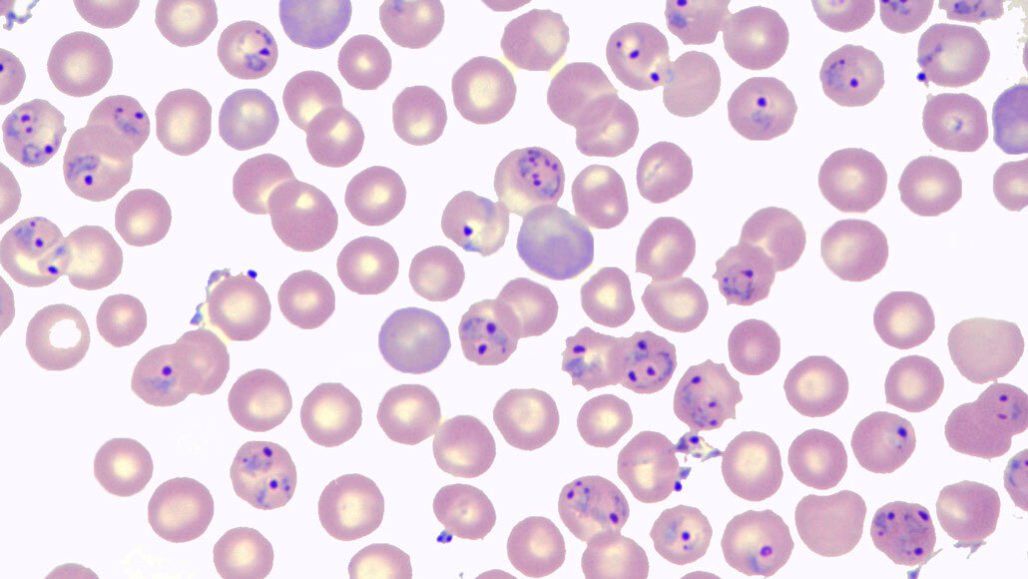

The malaria parasite pictured under a microscope. Joseph Takahashi Lab. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The reason these recent cases received so much attention were that all five were acquired locally within the US, which likely indicates that the parasitic mosquito population has made a resurgence as well. Thankfully, the species of parasite identified to have caused this small outbreak is known to transmit one of the milder forms of the disease, but that in no way detracts from the gravity of the situation. Matters of public health have become much more salient in regular discourse since the COVID-19 pandemic, and with it, some extreme opinions about containing and treating transmissible diseases. While America’s healthcare infrastructure continues to operate in largely the same way as it did during the 2003 outbreak, experts have agreed that public cooperation is now more important than ever if this re-appearance is to be nipped in the bud.

The RTS,S malaria vaccine. TheScientist. CC BY-SA 2.0

One particular area in which this agreement would go a long way, is that surrounding the efficacy of vaccines. In October of 2021, the WHO officially recommended the use of the RTS,S malaria vaccine developed by GlaxoSmithKline to prevent transmission in regions with high incidences of the disease. In addition to being logistically simple to store and administer, trials proved that the vaccine was beneficial to 90% of those treated, a staggering figure in the world of pharmaceutical development. Introducing the vaccine to the U.S. seems like an obvious step to take in the wake of these recent malaria cases, especially given the low price of a single dose at $9.30.

Vaccines have been a hotspot of controversy over the past few years, with many people denouncing both their safety and efficacy as a preventative treatment. Government authorities and healthcare professionals and academics around the world continue to release studies and evidence to show that vaccines are essential to build up individual and population-wide resistance to a variety of diseases, but large groups of the public still remain unconvinced. Among the many lessons and important takeaways from the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of vaccinations is among the most important, especially in the face of a potential re-emergence of a disease as deadly as malaria.

Tanaya Vohra

Tanaya is an undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health at the University of Chicago. She's lived in Asia, Europe and North America and wants to share her love of travel and exploring new cultures through her writing.

It’s Time to Decolonize Healthcare

Medicine has a long history of reinforcing colonial stereotypes.

Medical students at their induction ceremony at the University of Minnesota. Anthony Souffle. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Have you heard that women are 73% more likely to experience serious injuries in a car crash than men? If you are curious as to why, it’s because when designing airbags and other safety features, auto manufacturers use crash-test dummies based on measurements of the average male. These so-called safety precautions are engineered to protect only half of the world’s population. The scariest part, however, is that car manufacturing is not the only industry in which such blatant exclusion and discrimination occur. The practice of medicine, whose sole purpose is to treat and cure people, has recently come under fire for having a foundation rife with antiquated and colonial ideas, upholding social hierarchies that alienate not just women, but people of non-European heritage. The term “decolonizing” here refers to efforts to eliminate these racist, sexist and homophobic ideals that existed during the initial development of the Western Medicine, in favor of methods that recognize and successfully treat the whole, diverse range of patients. This need for a decolonization of healthcare became especially apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, as African Americans and Hispanic people were twice as likely to have severe cases of the disease as white Americans. Unfortunately, there is no equivalent of the average male crash-test dummy in this case. Western medicine as it is known and applied in many countries around the world has existed for hundreds of years, continuously cementing its elitist and exclusionary ideals.

Protestors in Portland, Oregon during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Spencer Platt. CC BY-SA 2.0

As with most disciplines, medicine is practiced the way it is taught. Exclusionary principles date all the way back to the very origins of the field: even Aristotle described the female body as a mutilated version of the male one. These and other, similar beliefs have trickled down through the years, resulting in the white, heterosexual, able-bodied man being considered the “average” patient, while everyone else is forced to fit the cookie cutter treatments and medical services designed for a fraction of the population. This results in huge gaps in specific medical knowledge about women, people of color and people with disabilities that are often either ignored by the medical community or, more dangerously, are filled by blaming other, unrelated causes.

A prime example of this appears in the controversial condition termed “female hysteria” which, for hundreds of years, has been used by doctors (especially male ones) to label any women’s symptoms or behaviors they did not recognize. Far from being a historical phenomenon, psychology is still used today to brush aside the symptoms of female patients. Dr. Kate Young, a public health researcher from Monash University in Australia, is one of many medical professionals who has published research on how female patients suffering from endometriosis are often referred to as “reproductive bodies with hysterical tendencies,” furthering the harmful idea that women are oversensitive to pain and therefore are more inclined to exaggerate their discomfort.

Improving access to health education is crucial to help female patients deal with medical gaslighting. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. CC BY-SA 2.0

Of course, women are just one of many groups who stand at a systemic disadvantage when receiving medical care and advice, and the effects of racism on the health of people of color and minority populations have been studied extensively for years. In 1992, Professor Arline Geronimus of the University of Michigan proposed a concept called “weathering,” which describes the pattern of early health deterioration among African Americans as the consequences of constant and repeated experiences with socio-political marginalization and discrimination. Almost three decades later, doctors are finally starting to make the connection between this more or less forgotten idea and the disproportionately high incidences for African Americans of high blood pressure, strokes and even colon cancer, along with a host of other conditions.

While contemporary racism, both structural and otherwise, is definitely to blame, we cannot ignore medicine’s long history of excluding Black and Brown bodies in science and research, not to mention medical textbooks, illustrations and even case studies. Historically, the main use of people of color for medical study was as test subjects in unethical experiments, with no intention of using the results to better the medical conditions of these minorities. The Tuskegee Experiments are often the first such example that comes to mind: a study in which American researchers deliberately infected African American men with syphilis under false pretenses, and proceeded to withhold care in order to track the natural progression of the disease. However, other similar “studies” have occurred time and time again, with The Aversion Project singling out LGBTQ+ members of the South African military between 1971 and 1989, or the US government-run Guatemalan syphilis experiments of 1947 which duplicated the Tuskegee study on Guatemalan immigrants to the US. Like female hysteria, the perception that certain people are less deserving of treatment and are therefore more expendable has leached into the modern medical landscape. Fixing such deep-rooted issues will not only require a huge increase in diversity within the medical profession, but also a serious push towards increasing our understanding of how medicine and disease is experienced by a wide range of people.

Nurses in New York advocating for healthcare justice. New York State Nurses Association. CC BY-NC 2.0

Ridding healthcare systems of their colonial foundations will not happen overnight, but there are many individuals and organizations who are working to foster change. Here are a few that you can learn about and support in their efforts to increase diversity and inclusivity in the medical community:

Dr. Annabel Sowemimo: In addition to being a noted doctor and academic, Dr Sowemimo is a prolific activist and writer, especially in regards to reproductive health. She founded the Reproductive Justice Initiative which focuses on reducing health inequalities and also published her first book earlier this year about racism in medicine titled “Divided: Racism, Healthcare, and Why We Need to Decolonize Healthcare.”

Mind The Gap: Founded in late 2019, this project culminated in medical student Malone Mukwende publishing a handbook with staff at St George’s University of London that highlights how a variety of medical conditions present on patients with darker complexions.

Dr. Nadine Caron: As the first female general surgeon of First Nations descent in Canada, Dr. Caron has long been an outspoken advocate for Indigenous people’s rights in both medical practice and research. In 2014, she co-founded the Center for Excellence in Indigenous Health at the University of British Columbia, her alma mater, which focuses on supporting research on Indigenous health.

Advancing Health Equity: Founded in 2019 by Dr Uché Blackstock, an internationally recognized doctor, advocate and speaker, this organization partners with medical institutions and gives professional training on how to provide racially equitable healthcare and medical services.

Tanaya Vohra

Tanaya is an undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health at the University of Chicago. She's lived in Asia, Europe and North America and wants to share her love of travel and exploring new cultures through her writing.