In Morocco, the word Kasbah is used to reference a bustling city center, a citadel, something kept apart from its rural counterparts.

Read MoreThe Sustainable and Empowering Bamboo Bikes of Ghana

The abundance of bamboo in Ghana led one company to produce sustainable bamboo bikes that are stronger than steel. In addition, they help their community by training young people in rural communities.

Read MoreHow Asia Transformed from the Poorest Continent in the World into a Global Economic Powerhouse

In 1820, Asia accounted for two-thirds of the world’s population and more than one-half of global income. The subsequent decline of Asia was attributed to its integration with a world economy shaped by colonialism and driven by imperialism.

By the late 1960s, Asia was the poorest continent in the world when it came to income levels, marginal except for its large population. Its social indicators of development, among the worst anywhere, epitomised its underdevelopment. The deep pessimism about Asia’s economic prospects, voiced by the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal in his 1968 book Asian Drama, was widespread at the time.

In the half century since then, Asia has witnessed a profound transformation in terms of the economic progress of its nations and the living conditions of its people. By 2016, as my analysis of UN data shows, it accounted for 30% of world income, 40% of world manufacturing, and over one-third of world trade, while its income per capita converged towards the world average.

This transformation was unequal across countries and between people. Even so, predicting it would have required an imagination run wild. Asia’s economic transformation in this short time-span is almost unprecedented in history. My new book, Resurgent Asia, looks at this phenomenal change.

Given the size and the diversity of the Asian continent, looking at the region as a whole is not always appropriate. So in my research, I’ve disaggregated Asia into its four constituent sub-regions – East, South-East, South and West Asia – and further into 14 selected countries described as the Asian-14. These are China, South Korea and Taiwan in East Asia; Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam in South-East Asia; Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka in South Asia; and Turkey in West Asia. These countries account for more than four-fifths of the population and income of the continent. Japan is not included in the study because it is a high income country in Asia, and was already industrialised 50 years ago.

The bright lights of Shenzen, China. zhangyang13576997233/Shutterstock

It’s essential to recognise the diversity of Asia. There have been marked differences between countries in geographical size, embedded histories, colonial legacies, nationalist movements, initial conditions, natural resource endowments, population size, income levels and political systems. The reliance on markets and the degree of openness of economies has varied greatly across countries and over time.

Across Asia, the politics has also ranged widely from authoritarian regimes or oligarchies to political democracies. So did ideologies, from communism, to state capitalism and capitalism. Development outcomes differed across space and over time too. There were different paths to development, because there were no universal solutions, magic wands, or silver bullets.

Absolute poverty persists

Despite such diversity, there are common discernible patterns. Economic growth drove development. Growth rates of GDP and GDP per capita in Asia have been stunning and far higher than elsewhere in the world.

Rising investment and savings rates combined with the spread of education were the underlying factors. Growth was driven by rapid industrialisation, often led by exports and linked with changes in the composition of output and employment. It was supported by coordinated economic policies, unorthodox wherever and whenever necessary, across sectors and over time.

Rising per capita incomes transformed social indicators of development, as literacy rates and life expectancy rose everywhere. There was also a massive reduction in absolute poverty. But the scale of absolute poverty that persists, despite unprecedented growth, is just as striking as the sharp reduction of poverty that happened between 1984 and 2012, according to data from the World Bank.

The poverty reduction could have been much greater but for the rising inequality. Inequality between people within countries rose almost everywhere, except South Korea and Taiwan. Yet the gap between the richest and poorest countries in Asia remains awesome and the ratio of GDP per capita in the richest and poorest country in Asia was more than 100:1 in both 1970 and 2016.

The role of governments

Economic openness has performed a critical supportive role in Asian development, wherever it was in the form of strategic integration with the world economy, rather than passive insertion into it. For example, trade policy was liberal for exports but restrictive for imports. Government policies towards foreign investment have been shaped by industrial policy in the pursuit of national development objectives. While openness was necessary for successful industrialisation, it was not sufficient and facilitated industrialisation only when combined with industrial policy.

In the half-century economic transformation of Asia, governments performed a vital role, ranging from leader to catalyst or supporter. Success at development in Asia was about managing this evolving relationship between states and markets, by finding the right balance in their respective roles that also changed over time.

The developmental states in South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore coordinated policies across sectors over time in pursuit of national development objectives, using carrot-and-stick policy to implement their agenda, and were able to become industrialised nations in just 50 years. China emulated these developmental states with much success, and Vietnam followed on the same path two decades later, as both countries have strong one-party communist governments that could coordinate and implement policies.

It is not possible to replicate these states elsewhere in Asia. But other countries, such as India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh and Turkey, did manage to evolve some institutional arrangements, even if less effective, that were conducive to industrialisation and development. In some of these countries, the checks and balances of political democracies were crucial to making governments more orientated towards development and people-friendly.

The rise of Asia represents the beginnings of a shift in the balance of economic power in the world and some erosion in the political dominance of the West. The future will be shaped partly by how Asia exploits the opportunities and meets the challenges and partly by how the difficult economic and political conjuncture in the world unfolds.

Yet it’s plausible to suggest that by around 2050, a century after the end of colonial rule, Asia will account for more than one-half of world income and will be home to more than half of the people on earth. It will have an economic and political significance in the world that would have been difficult to imagine 50 years ago, even if it was the reality in 1820.

Deepak Nayyar is an Emeritus Professor of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University and Honorary Fellow, Balliol College, University of Oxford

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Hidden in plain sight: the Kurdish question in Turkey. Sedat Suna/EPA

Why the Kurdish Conflict in Turkey is so Intractable

The ramifications of Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw US troopsfrom the Turkish-Syrian border continues to have a seismic effect on the situation in northern Syria.

Faced with the Turkish invasion of northern Syria, the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) who controlled the area were forced to make compromises. On October 13, they announced a deal with the Syrian army, which began moving troops towards the Turkish border. A five-day ceasefire was brokered by the US on October 18, during which Turkey agreed to pause its offensive to allow Kurdish forces to withdraw.

For many, the SDF proved itself to be the most effective force in the fight against Islamic State (IS). Turkey, however, considers the SDF as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which it, the US and EU label as a terrorist organisation.

But behind this lies a long history of Turkey denying the very existence of the Kurdish conflict, and the political and cultural rights of its Kurdish population. Understanding this history helps explain why the conflict is so intractable, and the impact it continues to have on Turkey’s foreign policy choices.

No room in the nation state

The Kurdish conflict cannot be understood without considering the question of power and exclusion. Its origins go back to the mid-19th century when the Ottomans attempted to end the 300-year-old autonomy of the Kurdish principalities in Kurdistan. This struggle for autonomy wasn’t resolved during the rule of the Ottoman era, and when it collapsed, all of the new nation states that eventually emerged – Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran – inherited their own Kurdish conflict.

The Turks and the Kurds fought a successful war of independencetogether in 1919 against the Allied forces. Nevertheless, when the new Republic of Turkey was established in 1923, Turkish identity was presented as its unifying force, at the expense of the society’s political, social and cultural differences.

Not only was political power further centralised in Ankara, but the domination of the ethnic, Turkish and Sunni majority became the norm. The decision to create a centralised and homogeneous nation state was implemented in a top-down and violent fashion. The seeds of the long-term problems that Turkish and Kurdish communities confront today were created by this decision.

Various Kurdish groups challenged this new social and political order with different revolts, uprisings, and resistance, but these were violently suppressed. Repressive policies of assimilation were later implemented to transform the Kurds into civilised and secular Turks.

A conflict buried

The Kurdish conflict laid buried for many years. Then, the most serious challenge to Turkey’s nation state project was initiated by the PKK in 1984, which embraced a political agenda called democratic autonomy. The violent struggle between Ankara and the PKK has resulted in a huge economic and human cost.

Peace talks which began in 2013 with the PKK’s jailed leader Abdullah Öcalan were widely considered to be the best chance for ending the conflict, but these collapsed in 2015. This led to increasing violence in the form of a destructive armed conflict in southeastern Turkey and a wave of bombings, including in Ankara and Istanbul.

The resolution of intractable conflicts is only possible when conflicted parties can confront their past and learn from it. In 2015, amid attempts by Turkish opposition parties to reopen peace negotiations with the Kurds, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan insisted: “There is no Kurdish conflict”. Such positioning, which continues today, keeps the political dimension of the conflict in the background.

Aftermath of a bomb attacking a military convoy in Diyarbakir, Turkey. EPA

The state carefully controls what can and cannot be said about the conflict. Typically, words such as “terror” and “traitor” are used to criminalise those who criticise government policy towards the Kurds. A group of academics who signed a petition in 2016 calling for the resumption of peace talks were charged with making “terrorism propaganda”. The non-violent wing of the Kurdish movement – activists, politicians, political parties – has also been criminalised.

Blame game

Instead of confronting their failure to bring about peace, Turkish political elites have tried to apportion blame elsewhere. Erdoğan, for example, repeatedly refers to an invisible “mastermind” who orchestrates the PKK. Such rhetoric is deployed to play on the collective fear and anxiety about national security felt by parts of Turkish society.

Some have called this the “Sèvres syndrome” – referring to the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres that marked the end of the Ottoman empire and proposed to divide it into small states and occupation zones. The treaty was never implemented, and superseded by the 1923 Lausanne Treatywhich recognised the Republic of Turkey.

This syndrome – also referred to as “Sèvres Paranoia” – in essence reflects the collective fear that the Treaty of Sèvres will be revived and that the Turkish state is encircled by enemies who want to divide and weaken the country.

Today, this line of thinking is an integral part of Turkish political life and continues to influence public perception towards the external world. In a 2006 public opinion survey, for example, 78% of participants agreed that “the West wants to divide and break up Turkey like they broke up the Ottoman Empire”.

Driving Turkey’s choices. By kmlmtz66/Shutterstock

In this way, the Kurdish conflict has been used to mobilise Turkish society to act against its own collective interest: a peaceful and just society. Policies aimed at managing the conflict have been implemented mostly within a state of emergency, in ways that continue to undermine Turkish democracy. Not only has the tremendous economic and human cost of the conflict become a “normal” part of Turkish life, but the state has also been successful in actively keeping the political dimension of the conflict at bay.

For a long time, Turkey refrained from talking about the Kurdish issue by assuming that it would eventually fade away. But it didn’t and instead, the conflict has become more deeply entrenched. Time will tell whether the Turkish state will ultimately gain or lose by its latest military intervention in Syria. However, what’s clear is that the Kurdish conflict will get more complicated with this latest move, and both the Turkish state and Turkish society will no longer be able to ignore it.

Recep Onursal is a PhD candidate in International Conflict Analysis, University of Kent

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

The Secret to Sriracha Hot Sauce’s Success

David Tran is the man to thank for the Sriracha Hot Chili Sauce you douse your scrambled eggs with every morning. You know the stuff. Red bottle with a green cap and a rooster on the front—plus five languages on the bottle—this simple sauce connects people from different cultures and backgrounds. “It never occurred to me that our hot sauce could get so much attention and acceptance from different people,” said Tran. Today, Tran oversees a hot sauce empire, but he comes from humble beginnings. He arrived in the United States from Vietnam 40 years ago as a refugee. So how did the founder of Huy Fong Foods turn his fresh, homemade hot sauce into an internationally-recognized brand and household staple? We visited his factory in Irwindale, California, to learn the secret to his sauce.

Panama Celebrates its Black Christ, Part of Protest Against Colonialism and Slavery

The life-sized wooden statue of the Black Christ in St. Philip Church in Panama. Dan Lundberg/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Panama’s “Festival del Cristo Negro,” the festival of the “Black Christ,” is an important religious holiday for local Catholics. It honors a dark, life-sized wooden statue of Jesus, “Cristo Negro” – also known as “El Nazaraeno,” or “The Nazarene.”

Throughout the year, pilgrims come to pay homage to this statue of Christ carrying a cross, in its permanent home in Iglesia de San Felipe, a Roman Catholic parish church located in Portobelo, a city along the Caribbean coast of Panama.

But it is on Oct. 21 each year that the major celebration takes place. As many as 60,000 pilgrims from Portobelo and beyond travel for the festival, in which 80 men with shaved heads carry the black Christ statue on a large float through the streets of the city.

The men use a common Spanish style for solemn parades – three steps forward and two steps backward – as they move through the city streets. The night continues with music, drinking and dancing.

In my research on the relationship between Christianity, colonialism and racism, I have discovered that such festivals play a crucial role for historically oppressed peoples.

About 9% of Panama’s population claims African descent, many of whom are concentrated in Portobelo’s surrounding province of Colón. Census data from 2010 shows that over 21% of Portobelo’s population claimAfrican heritage or black identity.

To Portobelo’s inhabitants, especially those who claim African descent, the festival is more than a religious celebration. It is a form of protest against Spanish colonialism, which brought with it slavery and racism.

History of the statute

Portobelo’s black Christ statue is a fascinating artifact of Panama’s colonial history. While there is little certainty as to its origin, many scholars believe the statue arrived in Portobelo in the 17th century – a time when the Spanish dominated Central America and brought in enslaved people from Africa.

Cristo Negro. Adam Jones/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Various legends circulate in Panama as to how the black Christ got to Portobelo. Some maintain that the statue originated in Spain, others that it was locally made, or that it washed ashore miraculously.

One of the most common stories maintains that a storm forced a ship from Spain, which was delivering the statue to another city, to dock in Portobelo. Every time the ship attempted to leave, the storms would return.

Eventually, the story goes, the statue was thrown overboard. The ship was then able to depart with clear skies. Later, local fishermen recovered the statue from the sea.

The statue was placed in its current home, Iglesia de San Felipe, in the early 19th century.

Stories of miracles added to its mystique. Among the legends in circulation is one about how prayers to the black Christ spared the cityfrom a plague ravaging the region in the 18th century.

Catholicism and African identity

Since its exact origins are unknown, so are the artistic intention behind the Jesus statue. However the figure’s blackness has made it an object of particular devotion for locals of African descent.

At the time of the arrival of Cristo Negro, the majority of the Portobelo’s population was of African descent. This cultural heritage is significant to the city’s identity and traditions.

The veneration of the statue represents one of many ways that the black residents of Portobelo and the surrounding Colón region of Panama have engendered a sense of resistance to racism and slavery.

Each year around the time of Lent, local men and women across Colón – where slavery was particularly widespread – dramatize the story of self-liberated black slaves known as the Cimarrones. This reenactment is one of a series of celebrations, or “carnivals,” observed around the time of Lent by those who identify with the cultural tradition known colloquially as “Congo.” The term Congo was originally used by the Spanish colonists for anyone of African descent. It is now is used for traditions that can be traced back to the Cimarrones.

During the carnival celebration, some local people dress up as the devil, meant to represent Spanish slave masters or complicit priests. Others don the dress of the Cimarrones.

Many of the participants in both the black Christ and carnival celebrations of Panama are Catholics as well. Together they participate to bring to light the Catholic Church’s complex relationship with Spanish colonization and slavery. Many Catholic leaders in the 16th to 18th centuries justified the enslavement of Africans and the colonization of the Americas, or at least did not object to it.

A revered tradition

The different colored robes that are put on the statue of Cristo Negro. Ali EminovFlickr, CC BY-NC

Many people from throughout Panama have donated robes to clothe the statue. The colors of the robes donned by the statue varies throughout the year. Purple is reserved for the October celebrations, which likely reflects the use of purple in Catholic worship to signify suffering.

These robes draped on Panama’s black Christ are meant to representthose placed on Jesus when he was mockingly dressed in royal garb by the soldiers torturing him before his crucifixion.

Evoking this scene perhaps serves to remind the viewer of the deeper theological meaning of Jesus’s suffering as it is often understood in Christianity: Although Jesus is the Son of God prophesied to save God’s people from suffering and should thus be treated like royalty, he was tortured and executed as a common criminal. His suffering is understoodto save people from their sins.

Some pilgrims specifically come during the October festival to seek forgiveness for any sinful actions. Some wear their own purple robes, the color indicating a sign of their suffering – and, of course, that of the black Christ.

S. Kyle Johnson is a Doctoral Student in Systematic Theology, Boston College

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

GREENLAND: Ilulissat Icefjord

Experience a beautiful timelapse trip to the Ilulissat Icefjord. This timelapse film project is made by photographer Bo Normander and timelapse expert Casper Rolsted.

For 27-Time Hopi High Cross-Country Champs, Running Is Tradition

Running isn’t simply a sport for the Hopi people. It’s a tradition with deep spiritual purpose. For centuries, Hopi runners carried messages to distant villages, and ran to springs to deliver prayers to bring rain. Rick Baker runs the cross country program at Arizona’s Hopi High Schoo, and his young athletes run the same dusty trails their ancestors blazed.

Read MoreFossil fuel industry sees the future in hard-to-recycle plastic

Fossil Fuel Industry sees the Future in Hard-to-Recycle Plastic

Plastic pollution and the climate crisis are two inseparable parts of the same problem, though they aren’t treated as such. Many countries have implemented plastic bag charges and plastic straw bans while action to phase out fossil fuels lags far behind, due in part to the inertia of the huge oil and gas companies that dominate the sector.

An investigation by The Guardian recently found that just 20 of these firms are responsible for 35% of global greenhouse gas emissions since 1965. How will they adapt as fossil fuel demand wanes with the rise of renewable energy and battery power? The answer is plastic – and that shift is already well underway.

Most of the plastic that exists today has been made in the last decade. The environment appears to be drowning in plastic for the same reason that global temperatures continue to rise – fossil fuels have remained cheap and abundant.

From filling up cars to plastic toy cars. Steinar Engeland/Unsplash, CC BY

Cheap plastic is made using chemicals produced in the process of making fuel. Petroleum refining transforms crude oil extracted from the ground into gasoline, producing ethane as a byproduct. A decade ago, the advent of fracking – hydraulic fracturing of oil or natural gas – made the raw materials for plastics significantly cheaper.

Fracking shale gas produces lots of ethane, which is turned into ethylene – the building block for many hard-to-recycle plastic products, like packaging films, sachets and bottles. Cheap polyethylene from fracking created a glut of plastic packaging on supermarket shelves that sociologist Rebecca Altman has called “frackaging”.

There are few facilities worldwide that can dispose of or recycle this kind of plastic efficiently. They’re expensive to set up and run and there’s little demand for using the recycled material to make new products. While packaging is the single largest source of plastic demand, most of that is thrown away as soon as it’s removed, with one third of it estimated to go directly to domestic waste and either incineration or landfill. In much of the world, a lot of it goes directly into the environment.

Reducing fuel consumption won’t necessarily solve the plastic problem. Global plastic production is expected to double in the next 15 years even as demand for gasoline wanes. In 2017, 50% of all crude oil produced worldwide was refined into fuel for transport, most as gasoline. Electric vehicles and more efficient forms of public transport mean gasoline demand is falling. The oil and gas companies who own these refineries are instead gearing up to turn what is now excess fuel into plastics for packaging.

Climate change in a bottle

As demand for gasoline continues to decline in future, more plastics will be made directly from crude oil. Petroleum companies now plan to convert up to 40% of the crude oil they intend to extract into petrochemicals. These are chemicals like acetylene, benzene, ethane, ethylene, methane, propane, and hydrogen, which form the basis for thousands of other products, including plastics.

The industry predicts petrochemicals will grow from 16% of oil demand in 2020 to 20% by 2040 largely to supply the feedstocks for making plastics. The environmental consequences of making even more plastic from crude oil will be significant. More plastic pollution will enter watercourses and the ocean, while amping up production will accelerate global emissions.

Read more: Plastic warms the planet twice as much as aviation – here's how to make it climate-friendly

That’s because making plastic releases carbon dioxide (CO₂). Both transporting the crude oil to make it and then disposing of the plastic by incineration generates emissions. Most of the estimated total natural capital cost of plastic pollution – USD$75 billion per year for the consumer goods sector alone – arises from CO₂ emissions linked to producing and transporting plastic.

Expanding plastic production and sending more plastic either directly to incineration or to waste-to-energy facilities - where plastics are turned into oil and used to generate electricity or heat – mean CO₂ emissions from plastic are expected to triple by 2050 to 309m metric tonnes. Incinerating mountains of plastic waste could become one of the largest sources of C0₂ emissions in Europe’s energy sector as fossil fuels are phased out.

Annual plastic production and use currently emits as much CO₂ each year as 189 500 megawatt coal power plants. CIEL, Author provided

Halving the use of petroleum-based plastic packaging by 2030 and phasing it out altogether by 2050 could ensure CO₂ emissions targets are still met. Achieving net zero emissions from incinerating plastic packaging means eliminating all non-essential uses of petroleum-based plastic by 2035, following a peak in packaging and other single use, disposable plastics in 2025. Replacing traditional plastics with new materials made from renewable sources like corn starch could help, as could developing a new infrastructure for industrial plastic composting.

In a climate crisis, plastic waste doesn’t look like the world’s most pressing environmental problem. But considering plastic and climate as two separate issues is a mistake. Concern about plastic pollution isn’t distracting people from a more serious problem – plastic is the problem. If we see plastics as “solid climate change”, they become central to the climate crisis.

DEIRDRE MCKAY is a Reader in Geography and Environmental Politics at Keele University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

For Young Refugees, a Mobile Phone can be as Important as Food and Water When Arriving in a New Country

Between 2015 and 2018, more than 200,000 unaccompanied children claimed asylum in Europe. Many of these young people, now in the EU, have one thing in common: their smart phones.

Digital tools are not only a means to keep in touch with friends and family. They can also become a lifeline for refugees and unaccompanied minors, according to a recent report, becoming as essential as food, water and shelter. But for many of these unaccompanied young children, out-of-date kit, lack of access to digital technologies and expensive mobile broadband packages can all act as barriers to being able to live in a digital environment.

Similarly, levels of literacy, can also significantly hinder technological development. And without structured educational provision, many young refugees can also struggle because of poor IT skills.

As researchers based in the UK and Hungary, we decided we wanted to help. And what began as a chance conversation at a conference in Prague, is now a major research project. The main aim of our two-year-long media literacy project was to understand how unaccompanied young refugees use digital technologies and social media.

We wanted to find out whether these technologies can help to foster successful integration. The fieldwork was carried out in four European countries with a high share of unaccompanied minors among asylum-seekers: Sweden, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK.

EU Calling

Our project involved interviews with 56 refugees, age 14-19, as well as their carers, mentors and educators. We met and observed the young people in their homes and community centres. We also carried out “digital ethnography” –- a type of online “audit” – on Facebook, with some of the children.

We found that young refugees can become easily lost when trying to access the digital world, needing multiple skills and tools to integrate successfully into a highly networked culture. The plethora of service providers, social media platforms and devices can be intimidating at first, but we were astonished at how quickly some of the young people we worked with were able to finds ways to negotiate their new digital circumstances – often after leaving war-torn countries.

A phone can be a lifeline for unaccompanied minors. Shutterstock/Marian Fil

From using translating apps, to communicate with locals, to downloading music from their own countries, some of these young people learned very rapidly how these tools work. That said, this was not the case for the majority of unaccompanied young people.

And for many, mentors or guardians were often the first point of aid when it came to problems encountered online. Older refugee children who have perhaps been in the new host country for some time – or have more familiarity with digital technologies – were also found to be key in helping new and arriving young people to better understand the digital world.

Digital navigation

We also found that many of the young people did not think too critically about their online experiences. And in an era of “fake news” they may be ushered into making poor judgements on what information to trust, and which opinions to follow. So for this reason we created an app called Media+Mentor specifically for mentors or educators who work with unaccompanied refugee youth.

The idea is that the Media+Mentor app will bring mentors and carers together. The app will also point users to further resources, support and advice on the most common issues unaccompanied minors face online – such as fake news, cyberbullying or hate speech.

From our findings, it’s clear that media literacy education is essential for these young people and their mentors. Indeed, for any teenager in the EU, popular apps and platforms are useful resources for learning new things, finding relevant information or simply as a way to connect with other young people. But as a refugee in a new country it can be hard to know how to access such help.

And these children are not just crossing physical borders, but are shifting into the heightened technological spaces that all EU youth probably take for granted. It has been estimated, for example, that 83% of young people across the EU use their smart phones to access the internet – and generally use fairly up-to-date kit.

So we hope that our research could help to provide young refugee people with the skills needed to stay safe and thrive – not only in the online world, but also in a new country where they are building new lives.

ANNAMARIA NEAG is a Marie Curie Research Fellow at the Bournemouth University.

RICHARD BERGER is an Associate Professor, Head of Research and Professional Practice, Department of Media Production, Bournemouth University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Cocoa production is an important cog in Ghana’s economy. Wikimedia Commons

Ghana’s Cocoa Farmers are Trapped by the Chocolate Industry

The chocolate industry is worth more than $80 billion a year. But some cocoa farmers in parts of West Africa are poorer now than they were in the 1970s or 1980s. In other areas, artificial support for cocoa farming is creating a debt problem. Farmers are also still under pressure to supply markets in wealthy countries instead of securing their own future.

In research published last year I explored sustainability programmes designed to support cocoa farming in West Africa. My aim was to identify winners and losers.

I looked at initiatives such as CocoaAction, a $500 million “sustainability scheme” launched in 2014, and concluded that they were done in the interests of large multinationals. They did not necessarily relieve poverty or develop the region’s economies. In fact they created new problems.

To sustain their livelihoods, the cocoa farmers of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana need to diversify away from cocoa production. But multinational chocolate companies need farmers to keep producing cocoa.

Diversification

Farmers choose to diversify their crops for a host of reasons. These include a reduction in the resources they need to produce a crop (such as suitable land), and a reduction in the price they can get for the crop.

Cocoa farming requires tropical forestland. This is limited; it is not possible to keep expanding to new land to keep producing cocoa. So when the land is exhausted, farmers would benefit from diversifying to products like rubber and palm oil. They do not need to grow cocoa for its own sake.

A great deal of diversification occurred during the cocoa crisis of the 1970s in Ghana. Cereal output increased from 388,000 tonnes in 1964/1965 to over 1 million tonnes in 1983/83, and decreased when cocoa was “revitalised”. The same was the case with coconut, palm oil and groundnut.

But such diversification is more recently being prevented by multinationals and other stakeholders who want cocoa cultivation to continue. Multinationals that depend on cocoa as a raw material openly (and rightly) regard diversification as a risk to their business. So they keep spending on cocoa farming inputs.

Why there’s a limit to cocoa

In West Africa, cocoa has historically been cultivated using slash and burn farming. Forest was cut down and burned before planting, and then, when the plot became infertile, the farmer moved to fresh forestland and did the same again.

The new land offered fertile soil, a favourable microclimate and fewer pests and diseases. Growing the cocoa took less labour and yielded more.

This explains the link between cocoa farming and deforestation in Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana. A recent investigation showed that since 2000, Ivorian cocoa has been dependent on protected areas. Almost half of Mont Peko National Park, for example, which is home to endangered species, as well as Marahoue National Park has been lost to cocoa planting since 2000.

In Côte d’Ivoire, the area covered by forest decreased from 16 million hectares – roughly half of the country – in 1960 to less than 2 million hectares in 2005.

Forestland is finite. Slash and burn is no longer an option, because so much of the forest is gone. In West Africa, planters are now staying on the same piece of land and reworking it.

This has created its own set of problems.

Rising costs and threats

In both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, several estimates of the cost of maintaining a cocoa farm show that the investment costs required for replanting have approximately doubled. One estimate of labour investment put the replanting effort at 260 days per hectare, compared with 74 days per hectare for planting using slash and burn.

The extra labour needed for sedentary cultivation is leading to child trafficking and child labour in cocoa cultivation. Child trafficking generally occurs when planters are searching for cheaper sources of labour for replanting.

Planters who have successfully diversified into other crops have stopped using child labour. In the cocoa industry, however, the use of child labour is increasing. For example, the number of child labourers in the Ivorian cocoa industry increased by almost 400,000 between 2008 and 2013.

There has also been a massive increase in the use of fertilisers and pesticides to aid cocoa production without slash and burn.

The increased input (labour, fertilisers and pesticides) for replanting land amounts to a higher production cost. It cannot be adjusted by price setting. Cocoa producers have no control over price; they are price takers. So the higher production cost reduces the profit made by cocoa farmers.

This explains why cocoa producers in Côte d’Ivoire are poorer now than they were decades ago.

In Ghana, the government, through the cocoa marketing board, COCOBOD, has managed the transition from slash and burn to sedentary farming. The government created a mass spraying programme to control diseases and pests. It also subsidised fertiliser and created a pricing policy that has sometimes amounted to a government subsidy this links need users to subscribe. Due to the extra free input provided by the government, sometimes supported by NGOs and multinational corporations, farmers have not become poorer in Ghana. But the approach has led to huge debt for COCOBOD. For example, COCOBOD incurred GHc2 billion (US$367 million) debt for subsidising the price of cocoa for the year 2017.

Although cocoa planters are faring well in Ghana, it is not clear that Ghana’s cocoa sector is really a success story. The shift to debt financing has artificially produced the success.

The way forward

Cocoa “sustainability” activities are not the way forward. Cocoa sustainability is a new form of colonisation in Africa, because its real goal is to prevent African planters from diversifying away from cocoa into other crops. These programmes keep the cocoa industry going under deteriorating conditions.

The way forward is to switch from cocoa to crops that do not require forestland (new or exhausted), extra fertilisers or more labour.

Research has shown that cocoa planters in Côte d’Ivoire who have diversified into other crops, such as rubber, have succeeded in escaping poverty.

But that is seen as a major threat to the supply of raw material to Western multinationals. One representative of a large chocolate multinational explained “my enemy is not my competitor in the purchase of cocoa, but the rubber industry.”

In conclusion, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have to think about what is best for them instead of what is best for the chocolate industry and consumers in the developed world.

MICHAEL E ODIJIE is a Post Doctoral Researcher at the University of Cambridge.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

The Call for Change: Women Speak Out on Sexualized Violence in South Africa

The tallies have been rising on women murdered on the streets of South Africa. From a country with a history of violence and suppression, the fight is nowhere finished. Multiday protests throughout major cities have brought the crisis to international attention.

Protest drawing awareness to rape victims at University of Cape Town. Devin O’Donnell.

The brutal murder of Uyinene Mrwetyana, a University of Cape Town student who was raped and killed while at the post office is unfortunately not a standalone incident. Mrwetyana joined upwards of 30 women that had been murdered in August alone. This marks the highest rates gender-based violence the country has seen, in a month that is, ironically, also designated as the national awareness month for Women’s Rights.

There are many reasons thought to be behind the high numbers. Culturally, it comes from a history of women being viewed as inferior and the belief that women must obey their husbands. In many parts of South Africa, there is a general acceptance of rape, including martial rape and gang rape, as not being seen as wrong. This has led to South Africa having the highest rate of domestic abuse in the world. Domestic abuse was only outlawed in 1998 and martial rape in 1993. A studied done by the South Africa Medical Research Council found that 50% of men have abused their partners. Most relevant to the recent murders, every six hours a partner kills their female counterpart and one in four men in South Africa have raped someone.

Studies have also found that there are certain traits in men and women that can lead to a greater risk of abuse in the country. Men who have grown up with violence, without father figures, and who use alcohol are more likely to abuse. It is also tied to race and socioeconomic status, as women of color, who are unemployed, and/or are from rural communities are more likely to be victims. Psychological studies have found that domestic abuse is often used as a response to feeling powerless. Apartheid proved violence is successful as a means for control and left people with a lack of trust in the government. Men who feel helpless regress to using violence against their partners in an attempt to regain a sense of control and self-worth. They also have a lack of fear of being prosecuted due to flaws in the police system – which is legitimate when only 15% of perpetrators are convicted.

The exceptionally high rates of HIV in South Africa pose an additional danger to rapes. The belief in a virgin cleansing myth, if you rape a virgin you will be cured of HIV, has led to high rates of abuse in children, with 50% of children being abused before they turn 18. Rates of sexual abuse have also been found to be exceptionally high in schools and often deters girls from pursuing education. Additionally, South Africa has increased rates of violence surrounding homophobia, with rates of “corrective rape” reaching 10 a week just in Cape Town. This mirrors statistics for gay black men.

President Ramaphosa said that measures have to be taken now to address the femicide. He has proposed longer sentencing and introducing more sexual offence courts. With current rates of rape reporting lingering at 2%, there is a chance that this will cause little change. The women marching firmly believe that change is necessary, but will it be enough?

DEVIN O’DONNELL’s interest in travel was cemented by a multi-month trip to East Africa when she was 19. Since then, she has continued to have immersive experiences on multiple continents. Devin has written for a start-up news site and graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in Neuroscience.

5 Women to Listen to When Thinking About Climate Advocacy

Greta Thunberg commanded the world’s attention with the urgency of her words before the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit, bringing to the forefront a conversation about the women who have been leading climate advocacy. While there are countless women who for decades have dedicated themselves to environmental activism, this article provides a shortlist of five women of all ages and walks of life who have promoted the common goal of a more sustainable world through their words and actions.

Dr. Sunita Nahrain presenting at the Stockholm Water Prize Symposium. Stockholm International Water Institute. CC 2.0

Sunita Narain, India: The director of the Center for Science and Environment in New Delhi, Nahrain has worked since the 1980s to build community partnerships focused on mitigating air pollution, as well as promoting food and water security. Nahrain has been a critical voice in the formation of climate policy in India, advising both the Environmental Pollution Authority for the National Capital Region, and a Joint Parliamentary Committee investigating pesticide contamination in foods. For her critical work Nahrain was awarded the World Water Prize in 2005, among numerous other honors throughout her career.

Hindou Omaraou Ibrahim Speaking before the World Economic Forum. World Economic Forum. CC 2.0

Hindou Omaraou Ibrahim, Chad: Ibrahim, a climatologist and environmental activist from Mbororo, Chad, has centered her work on the empowerment of indigenous women. She is the founder of the Association of Peul Women and Peoples of Chad, and was designated as the National Geographic Emerging Explorer in 2017. Ibrahim has spearheaded 3D mapping projects of Chad’s Sahel region, the home of the Mbororo community. The mapping efforts are partnered with UNESCO and the government of Chad, and are collecting thorough data regarding indigenous subsistence farming and environmental concerns, especially the drying of Lake Chad.

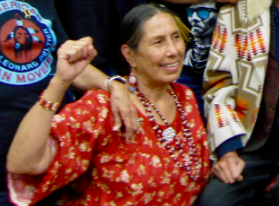

Casey Camp-Horinek, Wounded Knee AIM veterans. Neeta Lind. CC 2.0

Casey Camp-Horinek, United States: Camp-Horinek is a vocal environmental and indigenous rights activist on the behalf of the Ponca Nation, whose native land is located in the state of Oklahoma. Her advocacy deals directly with supporting grassroots activism against harmful industry practices such as fracking, and the construction of the Keystone XL natural gas pipeline. Camp-Horinek has dedicated herself to creating a platform for indigenous voices, serving as a board member for WECAN and presenting before the UN Forum on Indigenous Issues.

Shalvi Sakshi, Fiji: Sakshi, a twelve-year old climate activist from Bua, Fiji, served as the youngest panelist, then ten years old, for the 23rd Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in November of 2017 in Bonn, Germany. Sakshi urged of the dangers of rising sea levels due to deforestation and industrial contribution to rising carbon dioxide emissions. Her message is one of empowerment, emphasizing that everyone maintains the capacity and obligation to improve his or her world.

Changhua Wu Speaking before an EV20 Shanghai Media Event. The Climate Group. CC 2.0

Changhua Wu, China: Wu is an environmental advocate and social entrepreneur, who serves as the founding CEO of the Beijing Future Innovation Center and as the China/Asia Region Director for the Jeremy Rifkin Office. Wu has contributed extensively to important strides in clean energy policy in China, and has been recognized globally for her impact in the lowering of China’s carbon footprint. Combining her extensive background in economics, environmental policy, and journalism studies, throughout her career Wu has tied together sustainable technology, social entrepreneurialism, and environmental policy.

HALLIE GRIFFITHS is an undergraduate at the University of Virginia studying Foreign Affairs and Spanish. After graduation, she hopes to apply her passion for travel and social action toward a career in intelligence and policy analysis. Outside of the classroom, she can be found, quite literally, outside: backpacking, rock climbing, or skiing with her friends.

Peruventure

A chilling mix between fast cuts and slow pans, Peruventure will give you a raw yet whole picture of this South American country. Placing a specific emphasis on Peruvian children, you’ll see Peru from the Andes to the pacific coast.

Chinese Brides Wear as Many as Five Dresses – Yet Provide Inspiration for a Sustainable Fashion Future

Across the Northern hemisphere flowers are blooming, days are warmer and birds are singing. In China, where I live, there is another highly visible indicator of the season: couples dressed in their wedding day finest are to be seen posing in the most picturesque spots around the country, with a photographer in tow.

Weddings in China have always been opulent – with elaborate, detailed embroidered dresses and a prolonged series of ritual events – but in recent decades, as the country positions itself as a global leader and incomes increase, they have become even more so. Increasing Chinese popular awareness of global wedding dress and cultural trends have added to this opulence, with ever-increasing mix between Western and local traditions.

Weddings are now so central to Chinese culture that the small district of Tiger Hill in Suzhou has become the centre of the wedding dress industry, reportedly producing up to 80% of the world’s wedding dresses. This surge in in the industry has been fed by a new generation of Chinese brides and grooms that have become not only brand-conscious but brand-reliant.

Suzhou, China. 4045/Shutterstock.com

In a time in which sustainability has become a key goal for the global fashion industry, this trend is a worry. Here, issues in fast fashion seen all over the world, from wastefulness in production to cheaply produced goods made with poor quality synthetic fabrics, are magnified. And the wedding dress is an apt symbol for the excesses of the industry – usually a phenomenally expensive item, only ever worn once.

But despite the increasing rampant consumerism seen in Chinese wedding dresses, China does offer some kernels of hope for a world – and an industry – increasingly concerned by sustainability.

Tiger Hill

The city of Suzhou has for centuries been known throughout China as the city of silk and embroidery. But as the modern wedding culture of today’s China evolved, Tiger Hill Bridal Market area has developed: first as a centre for wedding photography studios, a place of studios and equipment, and then as a centre of wedding dress production and distribution. Situated just a few hundred metres from one of Suzhou’s famous tourist destinations, Tiger Hill, (Hu Qiu in Chinese) has morphed into a treasure trove of lace, taffeta and beads.

Shops in Tiger Hill offer every kind of imaginable incarnation of what a wedding dress could be, from a Han-Dynasty fantasy garment to a red or white princess-style gown to replicas of dresses worn by famous royal brides. While many shops cater to private customers, wholesalers who distribute the dresses via digital platforms also represent a large section of the area’s clientele.

The district, like many in China, has undergone rapid transformation since the turn of the new millennium, fuelled by an increasing number of consumers with a growing disposable income and associated wedding budget. Tiger Hill Wedding Market is now the place to buy your wedding dress in China as well as around the world online. Brides-to-be can source dresses at all price ranges, from ¥100 to ¥100,000 (approximately £9 to £9,000).

Shopping for dresses in Tiger Hill. © Sara Sterling, Author provided

But a key difference between Suzhou and other wedding dress markets is the prevalence of a rental culture, similar to the Western practice of suit and tuxedo rental for grooms and groomsmen.

This is a hangover from the pre-Deng Xiaoping Open era before the late 1970s, in which extravagant consumption practices were simply not available. And with a minimum of three dresses involved in the Chinese wedding day, it is no small wonder that renting remains well-established.

Multiple dresses

In the UK and other Western countries, it is becoming increasingly popular for brides to wear two versions of a bridal dress on the wedding day, with one reserved for the formal ceremony itself and the other for the evening reception, designed with comfort and ability to dance in mind.

But in China, brides wear up to five dresses. While two or possibly three dresses may have been standard in previous decades, this number has increased in recent years. The ideal bride in China is multi-dimensional, with dresses that represent not only different sections of the wedding day schedule, but different levels of the self. From a tightly fitted and hand-embroidered qi pao, to a voluminous white or cream-coloured dress reminiscent of the days of Marie Antoinette, brides aim to show themselves in different aspects throughout the day.

The photoshoot. Steve Heap/Shutterstock.com

There is one for the morning, when the bride is picked up by her groom after a series of verbal challenges and games. There is one for the walk into the banquet hall and arrival and one for the ceremony. Then another for the series of toasts as the bride and groom make their way around to the dozens of tables of well-wishers and red packet-givers, and perhaps even one more dress for the final hours of the evening.

This might sound over the top and rather wasteful. And indeed, increasing consumer demand for a larger number of dresses for each significant event of the wedding day has placed pressure on the wedding dress industry to produce a larger volume of dresses to meet these requests.

But it doesn’t have to be, especially if China doesn’t lose the tradition of renting these dresses. And with the price of rental dresses, or a rental dress package, costing up to tens of thousands of yuan, dress rental is still commonplace amongst Chinese brides, due to both economic necessity as well as the nature of the ceremony, with its multiple dress changes.

SARA STERLING is a Lecturer in Industrial Design at Xi'an Jiaotong Liverpool University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Thailand’s Modern Take on the Buddhist Temple

Wat Pha Sorn Kaew offers a modern take on the Buddhist temple. Built in the early aughts, this peaceful place of worship—known as the Temple on the Glass Cliff in English—is most notable for its five white Buddhas. You can see them for miles around. They are nestled together in meditation poses, arranged in descending order from tallest to smallest. The striking figures sit atop a five-level pagoda shaped like a lotus flower and covered in colorful mosaic tiles, stones and pottery. See why this temple is worth the five-hour drive from Bangkok.

Removing the Ghosts of Hurricane Maria from Puerto Rico’s Sea

Raimundo Chirinos has devoted his life and career to protecting Puerto Rico’s waters. And in the wake of Hurricane Maria, his devotion matters more than ever. Among its many assaults, the Category 5 storm pulled fishing gear from the island’s shores into the ocean, creating “ghost traps.” These misplaced traps inadvertently catch fish and other species, disrupting the ecosystem and the local fishing economy. More determined than ever to protect his island’s waters, Raimundo has hired local dive fishermen to help him locate ghost traps, creating economic opportunity and community in the wake of devastation.

This School on a Bus Is Bringing Education to Everyone

Shelia Hill grew up in San Francisco’s Sunnydale Projects. It was a rough neighborhood. She got into trouble when she was young and dropped out of school. She thought it wasn’t for her. Hill’s attitude changed after she had her own children. One day, her son asked why he should bother going to school since she didn’t. It was a lightbulb moment. Hill realized that she had to do better for herself and her family. She learned how to read and got her high school diploma through Five Keys, an organization that gives members of underserved communities a chance to restart their education. Today, Hill works for Five Keys as community ambassador. She goes out into neighborhoods considered education deserts on the Five Keys bus and encourages residents to board the mobile classroom where they can study with a teacher and earn their GEDs. Hill doesn’t want anyone to feel ashamed for not finishing school. So she always makes sure to share her own story, letting people know there was a time when she couldn’t read. And she’s big on follow-up with potential students. “I’ll call them. I’ll bug them. I’ll text them. I’ll email ’em. Whatever it takes,” she says. “I just want you to get your education. That’s it.”

Newborn babies in a Bangkok hospital on Dec. 28, 2017.They are wearing dog costumes to observe the New Year of the dog. Athit Perawongmetha/Reuters

What the US Could Learn from Thailand about Health Care Coverage

The open enrollment period for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) draws to a close on Dec. 15. Yet, recent assaults on the ACA by the Trump administration stand in marked contrast to efforts to expand access to health care and medicine in the rest of the world. In fact, on Dec. 12, the world observed Universal Coverage Day, a day celebrated by the United Nations to commemorate passage of a momentous, unanimous U.N. General Assembly resolution in support of universal health coverage in 2012.

While the U.N. measure was nonbinding and did not commit U.N. member states to adopt universal health care, many global health experts viewed it as an achievement of extraordinary symbolic importance, as it drew attention to the importance of providing access to quality health care services, medicines and financial protection for all.

Co-sponsored by 90 member states, the declaration shined a light on the profound effect that expansion of health care coverage has had on the lives of ordinary people in parts of the world with far fewer resources than the U.S., including Thailand, Mexico and Ghana. Can the U.S. learn anything from these countries’ efforts?

US and Thailand: A study in contrasts

I came to understand these changes as I researched and wrote my book, “Achieving Access: Professional Movements and the Politics of Health Universalism.” The book offers a comparative and historical take on the politics of universal health care and AIDS treatment, featuring Thailand as the primary case. For me, Thailand’s remarkable achievements also put into perspective some of the work we still have to do here in the United States with respect to health reform.

Before the reform, Thailand had four different state health insurance schemes, which collectively covered about 70 percent of the population. The reform in 2002 consolidated two of those programs and extended coverage to everyone who did not already receive coverage through the country’s health insurance programs for civil servants and formal sector workers.

Thailand’s universal coverage policy contributed to rising life expectancy, decreased mortality among infants and children, and a leveling of the historical health disparities between rich and poor regions of the country. The number of people being impoverished by health care payments also declined dramatically, particularly among the poor.

However, Thailand’s reform had other important consequences that aimed to make the reform sustainable as well. Sensible financing and gatekeeping arrangements – that tied patients to a medical home near where they lived and provided fixed annual payments for physicians to cover outpatient care – were instituted to curb the kind of cost escalation that has historically been a hallmark of the United States (though it has slowed lately). The reform also improved the quality of care for patients in remote areas by mandating that qualified providers in community hospitals collaborate more extensively with rural health centers.

A computer screen promoting this year’s open enrollment, which will run 45 days. In years past, open enrollment continued for months. Ricky Kresslein/Shutterstock.com

The United States, by contrast, seems to be moving in the opposite direction, both in terms of insurance coverage and health outcomes. Although recent Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act were narrowly defeated, lawsuits that aim to terminate popular pre-existing conditions protections continue. In addition, the Trump administration has sought to weaken the reform in other ways: including by cutting the open enrollment periods, which ends Dec. 15 and lasts 45 days; cutting outreach and advertising for open enrollment; and threatening to suspend risk adjustment payments to private insurers, which help to stabilize the market.

Moreover, effective repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate through a provision in the 2017 Tax Reconciliation Act that reduces the penalty for not having insurance to zero in 2019 will have the effect of reducing the number of insured. This will have an effect on health insurance markets, likely reducing the number of younger and healthier people that help give balance to health insurance risk pools and that help keep overall costs down. And without the financial protection afforded by health insurance, those who are uninsured may face rising rates of medical bankruptcy, to say nothing for the loss of access to sorely needed medical care.

Learning from Thailand

To be sure, the Thai and American contexts are very, very different. While health spending stands at around 4 percent of GDP in Thailand, in America nearly 20 percent, or one-fifth, of the country’s total economic output is spent on health. Yet, in some ways, that makes Thailand’s achievement all the more remarkable. And while no program is perfect, Thailand’s reform is one of the reasons that health costs in Thailand have remained so low, despite such a dramatic increase in coverage.

The use of generic drugs in Thailand is a strategy to keep costs low. Room's Studio/Shutterstock.com

Reformers also drew on other innovative policy instruments to keep costs down, including the Government Pharmaceutical Organization that produces generic medication for the universal coverage program and the use of compulsory licenses, which allow governments to produce or import generic versions of patented medication under WTO law.

The Affordable Care Act similarly sought to improve access, while curbing costs. Some of the most important mechanisms to curb costs fell victim to the legislative process however. Most notably, lobbyists succeeded in killing the “public option,” a government (as opposed to private) health insurer with much lower administrative costs that aimed to bring costs down among private health insurers through competition with them.

Although the reform in Thailand was popular among the masses, it also saw its share of detractors. Medical associations that represented doctors who saw the policy as a threat came out against it. Likewise, beneficiaries of the existing programs for civil servants and employees of large, tax-paying businesses feared that their own benefits would be diluted by a new single payer program. Despite progress expanding access to everyone, the new program introduced in 2002 still sits alongside separate programs for civil servants and employees of large, tax-paying businesses.

What the contrast makes clear, however, is that reforms done properly can expand access while at the same time instituting measures that help to contain costs. The U.S., in my view, should pursue similarly creative and constructive reforms that seek to do both.

What does that look like in the United States? To me, that means preserving the ACA’s individual mandate and protections related to pre-existing conditions; creating (or expanding) a public insurer like Medicare to compete alongside private insurers and keep costs down; addressing the lack of price transparency in our nation’s hospitals; and actively negotiating with pharmaceutical companies and hospitals to bring costs of drugs and health care down for millions.

Done sensibly, developing nations like Thailand are proving that they do not have to join the ranks of the world’s wealthiest nations for their citizens to enjoy access to health care and medicine. Using evidence-based decision-making, even expensive benefits, like dialysis, heart surgery and chemotherapy, need not remain out of reach. Policymakers in all countries can institute reforms using tools that promote cost savings at the same time they improve access and equity.

While efforts to implement universal coverage are not without challenges, these results suggest that leaders in Congress would do well to learn from countries like Thailand as they chart a fiscally responsible path forward on health care.

JOSEPH HARRIS is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Boston University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Surfing Under Northern Lights

Adventure photographer Chris Burkard is an expert at photographing surfers who ride the coldest, most punishing waves on the planet. He's used to battling the elements in order to get the perfect shot, but one fateful storm in Iceland nearly broke him. Still, he couldn't pass up the opportunity to capture an epic adventure under the greatest light show on earth.