The city has enacted sustainability initiatives that consistently earn recognition for eco-friendly daily living.

Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, is known for being ‘green’ due to its lush landscape and eco-friendly living. The small city, surrounded by the Alps and the Adriatic, has a population of roughly 290,000 residents. The city was awarded the European Green Capital award in 2016 for its commitment and vision for an eco-friendly city. Locals are dedicated to creating a sustainable city and take the green initiatives seriously. In 2008, the city center was deemed a zone free of motor vehicles. As a result, many people use bicycles to get around the city, and Ljubljana has become very bike-friendly to accommodate the influx of cyclists. The city has a free bike sharing network that allows residents and visitors to easily commute throughout the city. The city also has an eclectic vehicle service that can be hailed on the street as another form of public transportation in the city center.

Ljubljana is not only dedicated to sustainable transportation. Beekeeping is at the heart of Slovenian culture and thrives in Ljubljana. While the rest of Europe is experiencing a concerning decline in their bee population, Slovenia’s bee’s are thriving. Bees are essential to the environment and ecological systems, and Slovenia’s dedication to beekeeping is an essential part of what makes them an eco-friendly destination. Ljubljana has established urban beekeeping, with over 4,500 hives in the city. Beekeeping in Ljubljana can be traced back to the Bronze Age and remains an integral part of the city’s culture. To keep beekeeping thriving today, the city of Ljubljana started The Bee Path, a group of people who promote activities related to urban beekeeping and encourage co-existance with bees in an urban setting. Created in 2015, the path takes visitors throughout the city to learn about the importance and history of beekeeping in Ljubljana.

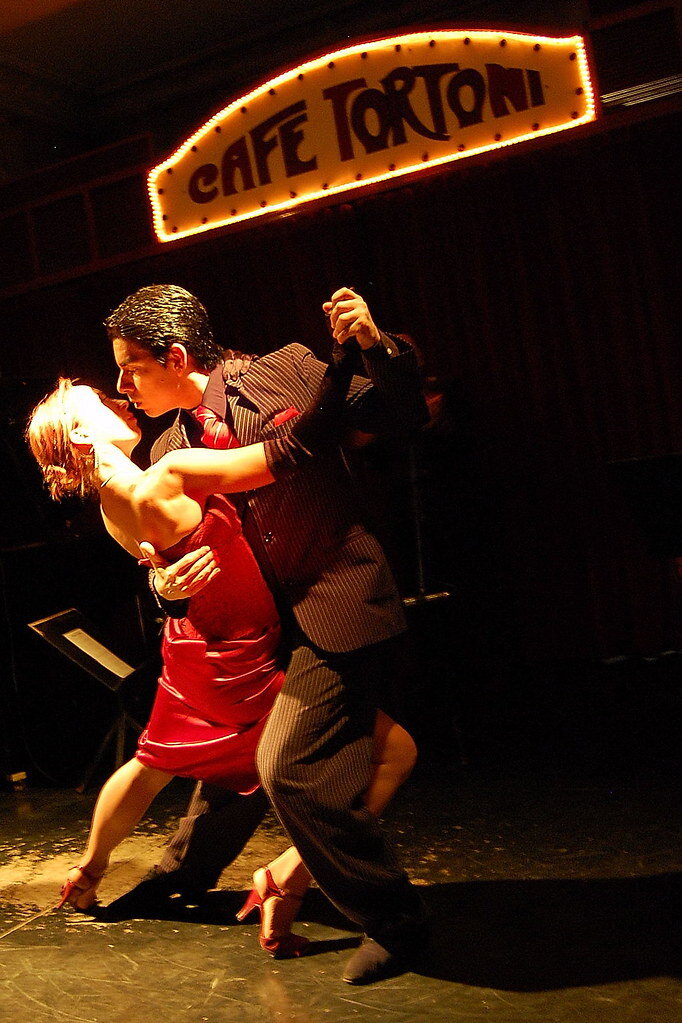

"Ljubljana, Slovenia" by szeke is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Ljubljana is known for its natural beauty and, prior to winning the Green Capital award in 2016, the city planted thousands of trees to add to the existing greenery. There are currently 65,000 registered trees in the cityMany of these trees are located along the city’s Path of Remembrance and Comradeship, which follows the location of barbed wire placed in the city during the World War II occupation. Today, the path is surrounded by trees and is used as a trail for joggers and bikers.

The city has a noticeably large amount of per capita green space, at 542 square meters. The city is also the first capital in the European Union to announce a zero waste initiative.The eco-friendly commitment is not just limited to Ljubljana; Slovenia itself was declared the first green destination in the world in 2017, meeting 96 of the 100 environmental initiatives. Ljubljana’s eco-friendly character is the result of the local community and government passionately making sustainable changes.

Dana Flynn

Dana is a recent graduate from Tufts University with a degree in English. While at Tufts she enjoyed working on a campus literary magazine and reading as much as possible. Originally from the Pacific Northwest, she loves to explore and learn new things.