While Western countries move to embrace the LGBTQ+ community, people of non-binary gender in India have played an important role in the society’s history and culture for over 4000 years.

Evidence of sexual ambivalence has been a recurring theme in ancient holy texts in which Hindu deities often change genders. In various Hindu scriptures, Hijras are seen as demi-gods who have historically played important roles as entrusted advisors to rulers. Hijras are born male but look and dress as female — many will undergo castration and offer their male genitalia to the Hindu goddess Bahuchara Mata. Bahuchara Mata is a pivotal deity who enjoys the patronage of the transgender community in India.

Life as a Hijra, or Kinnar (mythological beings that excel at song and dance) as they prefer to call themselves, is often a difficult one because while someone they may be revered they can also be disdained. Often cast out by their families they become open to exploitation, forces sex work and dangerous castrations. Community networks help to overcome this alienation by forming “houses” or “families” led by a Guru/teacher in order to support themselves by dancing and performing rituals. The connection to male/female characters in holy texts leads many to believe that the Hijra possess special powers and they earn a living by attending weddings and birth ceremonies to dance and offer blessings. To many Hindus, a Hijra’s blessing will mean long life and prosperity for the child. After a marriage ceremony the couple will receive a fertility blessing. It’s believed that the Hijra’s act of sacrificing their ability to procreate to the goddess Bahuchara Mata gives them their incredible religious power.

During the British colonization of India, the fluidity of gender was repressed, transgender practices were outlawed, and they were forced underground. In recent years, the Hijra have regained some of the rights and freedoms that were formerly denied. In 2014 the Supreme Court acknowledged that third gender people are deserving of rights equal to other citizens. They are slowly assimilating into the fabric of Indian society and are now recognised as a third gender on passports and other official documents.

Additionally, there have been several events in the recent past which indicate a move to more inclusive sexual variance in society. In 2019 The Hijra were invited to take part in the Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj, one of the largest holy bathing festivals in India. They were led by Laxmi Narayan Tripathi, a well-known Bollywood actress and activist for transgender rights in India. When invited to speak at the Asia Pacific UN Assembly in 2008, she spoke of the plight of sexual minorities claiming that transgender people should be respected as humans and given equal rights. After centuries of ostracism, the Hijra community’s fight to be accepted by the Hindu establishment is slowly reaching fruition.

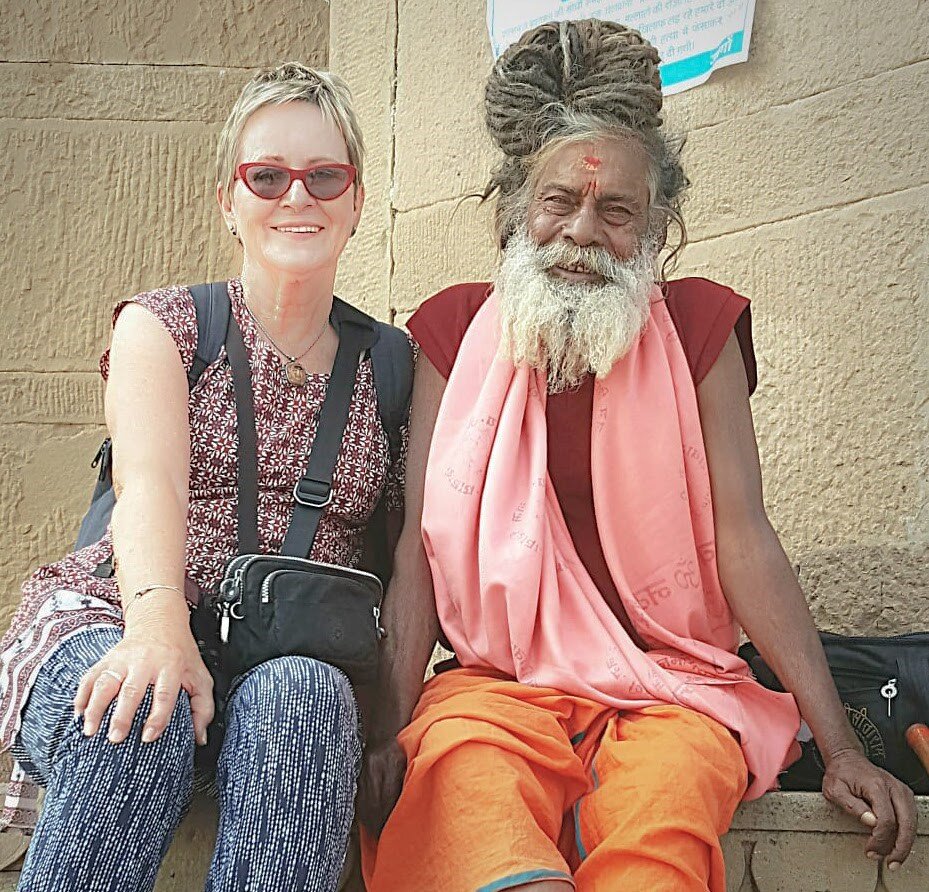

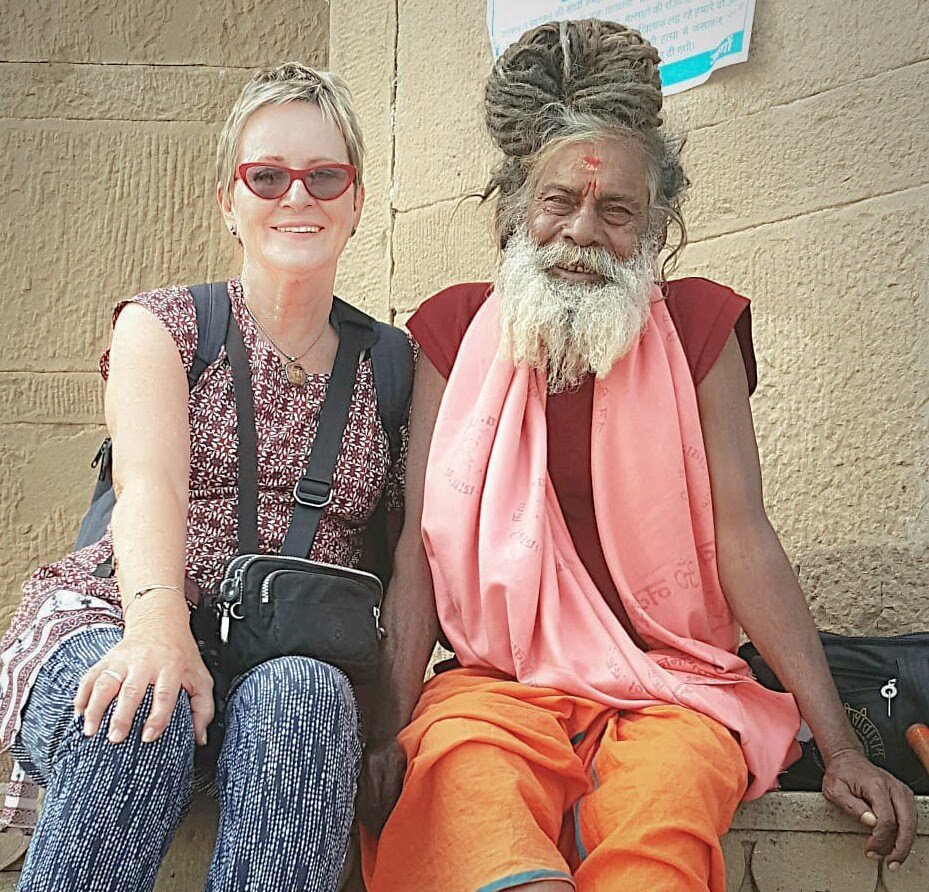

Carol Foote

Carol is based in Queensland Australia and has always been drawn to street photography, searching out the most colourful and quirky characters in her own environment. After studying documentary photography at college, she travelled to Yunnan, China to photograph the wide diversity of ethnic minorities in the region. However, over the past five years, her focus has shifted to Tibet, Nepal and India. As someone who has always been drawn to unique and different cultures, the regions rich heritage and local traditions make it a haven for her style of photography.

Follow Carol on social media @carolfoote_photographer

Check out more of Carol’s photography here

PHOTO ESSAY: Tibetan Worship and Culture at Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple