A few miles south of San Diego lies Tijuana, a favorite weekend getaway for Americans. Some Californians have even taken to living in Tijuana permanently to escape their state’s rising housing costs. However, life in Tijuana has changed drastically over the last few years as conflicts between rival drug cartels have caused the city’s murder rate to skyrocket. The situation presents a new set of risks for those wanting to visit the ever-popular tourist trap.

Read MoreAmerica’s public schools were meant to bring together children from all walks of life. Monkey Business Images/www.shutterstock.com

America’s Public Schools Seldom Bring Rich and Poor Together – and MLK Would Disapprove

Five decades after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., many carry on his legacy through the struggle for racially integrated schools. Yet as King put it in a 1968 speech, the deeper struggle was “for genuine equality, which means economic equality.” Justice in education would demand not just racially integrated schools, but also economically integrated schools.

The fight for racial integration meant overturning state laws and a century of history – it was an uphill battle from the start. But economic integration should have been easier. In the mid-18th century, when education reformers first made the case for inclusive and taxpayer-supported education, they argued that “common schools” would ease the class differences between children from different backgrounds.

As Horace Mann, the most prominent of these reformers, argued in 1848, such schools would serve to counter the “domination of capital and the servility of labor.” Learning together on common ground, rich and poor would see themselves in common cause – a necessity for the survival of the republic.

More than 150 years later, the nation has yet to realize this vision. In fact, it has been largely forgotten. Modern Americans regularly scrutinize the aims and intentions of the Founding Fathers; but the early designs for public education – outlined by Mann, the first secretary of education in Massachusetts, as well as by leaders like Henry Barnard, Thaddeus Stevens, and Caleb Mills – are mostly overlooked. Today, the average low-income student in the U.S. attends a school where two-thirds of students are poor. Nearly half of low-income students attend schools with poverty rates of 75 percent or higher.

Education historians, like myself, have generally focused their research and attention on racial segregation, rather than on economic segregation. But as income inequality continues to deepen, the aim of economically integrated schools has never been more relevant. If we are concerned with justice, we must revitalize this original vision of public education.

Shared community

Early advocates of taxpayer-supported common schools argued that public education would promote integration across social classes. They thought it would instill a spirit of shared community and open what Horace Mann called “a wider area over which the social feelings will expand.”

Horace Mann (1796-1859) was an early advocate of public education in the U.S. Fotolia/AP

And, generally speaking, it worked. The ultra-rich mostly continued to send their children to private academies. But many middle- and upper-income households began to send their children to public schools. As historians have shown, economically segregated schools did not systematically emerge until the mid-20th century, as a product of exclusionary zoning and discriminatory housing policies. Schools weren’t perfectly integrated by any means, particularly with regard to race. They were, however, vital sites of cross-class interaction.

Many prominent Americans – including U.S. presidents – were products of the public schools. Commonly, they sat side by side in classrooms with people from different walks of life.

But over the past half-century, students have been increasingly likely to go to school with students from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. Since 1970, residential segregation has increased sharply, with twice as many families now living in either rich or poor neighborhoods – a trend that has been particularly acute in urban areas. And segregation by income is most extreme among families with school-age children. Poor children are increasingly likely to go to school with poor children. Similar economic isolation is true of the middle and affluent classes.

Contemporary Americans commonly accept that their schools will be segregated by social class. Yet the architects of American public education would have viewed such an outcome as a catastrophe. In fact, they might attribute growing economic inequality to the systematic separation of rich and poor. As Horace Mann argued, it was the core mission of public schools to bring different young people together – to consider not just “what one individual or family needs,” but rather “what the whole community needs.”

Many parents do continue seek out diverse schools. A number of school districts have worked to devise student assignment plans that advance the aim of integration. And some charter schools are reaching this market by pursuing what has been called a “diverse-by-design” strategy. As demonstrated by research, diverse schools can and often do improve achievement across a range of social and cognitive outcomes, such as critical thinking, empathy and open-mindedness.

Largely overlooked, however, has been the political benefit of integrated schools. One rarely encounters the once-common argument that the health of American democracy depends on rich and poor attending school together. This is particularly surprising in an age of tremendous disparities in wealth and power. Members of Congress, on average, are 12 times wealthier than the typical American. Moreover, lawmakers are increasingly responsive to the privileged, even at the expense of middle-class voters.

If elites are isolated from their lower- and middle-income peers, they may be less likely to see a relationship of mutual commitment and responsibility to those of lesser means. As scholars Kendra Bischoff and Sean F. Reardon have argued, “If socioeconomic segregation means that more advantaged families do not share social environments and public institutions such as schools, public services, and parks with low-income families, advantaged families may hold back their support for investments in shared resources.”

What can be done?

Today more than 100 school districts or charter school chains work to integrate schools economically. Cambridge, Massachusetts, for instance, has four decades of experience balancing enrollments by social class, seeking to match the diversity of the city as a whole in each school.

This, of course, is only possible in a diverse place. Median family income in Cambridge is roughly US$100,000, while 15 percent of city residents live below the poverty line. It is also made possible through heavy investments in public education in the city. After all, it is far easier to convince middle-class and affluent parents to send their children to the public schools when per-pupil expenditures rival the highest-spending suburbs, as they do in Cambridge.

But not every district has Cambridge’s advantages. Nor does every district have similar political will.

The latter of those two constraints, however, may soon begin to change. Faced with a growing divide between rich and poor, Americans may begin to demand schools that not only serve young people equally from a funding standpoint, but also educate them together in the same classrooms.

Common schools by themselves are not enough to solve the problem of economic inequality. Yet if Americans seek to create a society in which the rich and the poor see themselves in common cause, common schools may be a necessary – and long overdue – step. We must come to see, in the words of Martin Luther King, that, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

Jack Schneider is an Assistant Professor of Education at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Genking, a male-born Japanese TV personality and ‘genderless’ pioneer. _genking_/Instagram

Japan’s Gender-Bending History

I’m an anthropologist who grew up in Japan and has lived there, off and on, for 22 years. Yet every visit to Tokyo’s Harajuku District still surprises me. In the eye-catching styles modeled by fashion-conscious young adults, there’s a kind of street theater, with crowded alleyways serving as catwalks for teenagers peacocking colorful, inventive outfits.

Boutiques are filled with cosmetics and beauty products intended for both males and females, and it’s often difficult to discern the gender of passersby. Since a gendered appearance (“feminine” or “masculine”) often (but not always) denotes the sex of a person, Japan’s recent “genderless” fashion styles might confuse some visitors – was that person who just walked by a woman or a man?

Although the gender-bending look appeals equally to young Japanese women and men, the media have tended to focus on the young men who wear makeup, color and coif their hair and model androgynous outfits. In interviews, these genderless males insist that they are neither trying to pass as women nor are they (necessarily) gay.

Some who document today’s genderless look in Japan tend to treat it as if it were a contemporary phenomenon. However, they conveniently ignore the long history in Japan of blurred sexualities and gender-bending practices.

Sex without sexuality

In premodern Japan, aristocrats often pursued male and female lovers; their sexual trysts were the stuff of classical literature. To them, the biological sex of their pursuits was often less important than the objective: transcendent beauty. And while many samurai and shoguns had a primary wife for the purposes of procreation and political alliances, they enjoyed numerous liaisons with younger male lovers.

Only after the formation of a modern army in the late-19th century were the sort of same-sex acts central to the samurai ethos discouraged. For a decade, from 1872 to 1882, sodomy among men was even criminalized. However, since then, there have been no laws in Japan banning homosexual relations.

It’s important to note that, until very recently, sexual acts in Japan were not linked to sexual identity. In other words, men who had sex with men and women who had sex with women did not consider themselves gay or lesbian. Sexual orientation was neither political nor politicized in Japan until recently, when a gay identity emerged in the context of HIV/AIDS activism in the 1990s. Today, there are annual gay pride parades in major cities like Tokyo and Osaka.

In Japan, same-sex relations among children and adolescents have long been thought of as a normal phase of development, even today. From a cultural standpoint, it’s frowned upon only when it interferes with marriage and preserving a family’s lineage. For this reason, many people will have same-sex relationships while they’re young, then get married and have kids. And some even later resume having same-sex relationships after fulfilling these social obligations.

Contentious cross-dressing

Like same-sex relationships, cross-dressing has a long history in Japan. The earliest written records date to the eighth century and include stories about women who dressed as warriors. In premodern Japan, there were also cases of women passing as men either to reject the prescribed confines of femininity or to find employment in trades dominated by men.

‘Modern girls’ (‘moga’) stroll along the Ginza, Japan’s Fifth Avenue, in 1928. Wikimedia Commons

A century ago, “modern girls” (moga) were young women who sported short hair and trousers. They attracted media attention – mostly negative – although artists depicted them as fashion icons. Some hecklers called them “garçons” (garuson), an insult implying unfeminine and unattractive.

Gender, at that time, was thought of in zero-sum terms: If females were becoming more masculine, it meant that males were becoming feminized.

These concerns made their way into the theater. For example, the all-female Takarazuka Revue was an avant-garde theater founded in 1913 (and is still very popular today). Females play the parts of men, which, in the early 20th century, sparked heated debates (that continue today) about “masculinized” women on stage – and how this might influence women off the stage.

However, today’s genderless males aren’t simply weekend cross-dressers. Instead, they want to shatter the existing norms that say men must dress and present themselves a certain way.

They ask: Why should only girls and women be able to wear skirts and dresses? Why should only women be able to wear lipstick and eye shadow? If women can wear pants, why shouldn’t men be able to wear skirts?

Actually, the adjective “genderless” is misleading, since these young men aren’t genderless at all; rather, they’re claiming both femininity and masculinity as styles they wear in their daily lives.

In this regard, these so-called genderless men have historical counterparts: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, cosmopolitan “high collar” men (haikara) wore facial powder and carried scented handkerchiefs, paying meticulous attention to their Westernized appearances. One critic – invoking the zero-sum gender attitudes of the era – complained that “some men toil over their makeup more than women.” Conservative pundits derided the haikara as “effeminate” by virtue of their “un-Japanese” style.

On the other end of the masculinity spectrum were the nationalistic “primitive” men (bankara) who wore wooden clogs (geta) to complement their military-style school uniforms. Ironically, like their samurai predecessors – and unlike the foppish haikara – the macho bankara would engage in same-sex acts.

Japan’s ‘beautiful youths’

Probably the biggest contemporary inspiration for today’s genderless males are a spate of popular androgynous boy bands. Cultivated and promoted by Johnny & Associates Entertainment Company, Japan’s largest male talent agency, they include boy bands like SMAP, Johnny’s West and Sexy Zone.

Johnny’s West performs their song ‘Summer Dreamer.’

There’s a term for the type of teenage boy that Johnny & Associates cultivates: “beautiful youths” (bishōnen), which was coined a century ago to describe a young man whose ambiguous gender and sexual orientation appealed to females and males of all ages.

Similarly, Visual Kei is a 1980s glam-rock and punk music genre that features bishōnen performers who don flamboyant, gender-bending costumes and hairdos. In its new, 21st-century incarnation as Neo-Visual Kei, the emphasis on androgyny is even more pronounced, as epitomized by the prolific career of the androgynous Neo-Visual Kei pop star Gackt, who enjoys an international fan following.

Since the word “genderless” is misleading, a better term might be “gender-more,” in the sense that young men – especially in Tokyo – are insisting on the right to present and express themselves in ways that contradict and exceed traditional masculinity. In the long span of Japanese cultural history, there have been many things that were – and are – new under the sun. But genderless males aren’t among them.

JENNIFER ROBERTSON is a Professor of Anthropology and Art History at the University of Michigan.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Mourners wait to attend the funeral of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, Virginia, Aug. 16, 2017 after Heyer was killed attending a rally to protest white nationalism. Julia Rendleman/AP Photo

Why Bigotry is a Public Health Problem

Over a decade ago, I wrote a piece for a psychiatric journal entitled “Is Bigotry a Mental Illness?” At the time, some psychiatrists were advocating making “pathological bigotry” or pathological bias – essentially, bias so extreme it interferes with daily function and reaches near-delusional proportions – an official psychiatric diagnosis. For a variety of medical and scientific reasons, I wound up opposing that position.

In brief, my reasoning was this: Some bigots suffer from mental illness, and some persons with mental illness exhibit bigotry – but that doesn’t mean that bigotry per se is an illness.

Yet in the past few weeks, in light of the hatred and bigotry the nation has witnessed, I have been reconsidering the matter. I’m still not convinced that bigotry is a discrete illness or disease, at least in the medical sense. But I do think there are good reasons to treat bigotry as a public health problem. This means that some of the approaches we take toward controlling the spread of disease may be applicable to pathological bigotry: for example, by promoting self-awareness of bigotry and its adverse health consequences.

In a recent piece in The New York Times, health care writer Kevin Sack referred to the “virulent anti-Semite” who carried out the horrific shootings at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh on Oct. 27, 2018.

It’s easy to dismiss the term “virulent” as merely metaphorical, but I think the issue is more complicated than that. In biology, “virulence” refers to the degree of pathology, or damage, caused by an organism. It differs from the term “contagious,” which refers to a disease’s communicability. But what if, in an important sense, bigotry is both virulent and contagious – that is, capable of both causing damage and spreading from person to person? Wouldn’t a public health approach to the problem make sense?

The harm to victims and to haters

There is little question among mental health professionals that bigotry can do considerable harm to the targets of the bigotry. What is more surprising is the evidence showing that those who harbor bigotry are also at risk.

For example, research by psychologist Dr. Jordan B. Leitner has found a correlation between explicit racial bias among whites and rates of circulatory disease-related death. Explicit bias refers to consciously held prejudice that is sometimes overtly expressed; implicit bias is subconscious and detected only indirectly.

In effect, Leitner’s data suggest that living in a racially hostile community is related to increased rates of cardiovascular death for both the group targeted by this bias – in this case blacks – as well as the group that harbors the bias.

A woman protests racism at a London rally.John Gomez/Shutterstock.com

Writing in the journal Psychological Science, Leitner and his colleagues at the University of California Berkeley found that death rates from circulatory disease are more pronounced in communities where whites harbor more explicit racial bias. Both blacks and whites showed increased death rates, but the relationship was stronger for blacks. Although correlation does not prove causation, clinical psychology professor Vickie M. Mays and colleagues at UCLA have hypothesized that the experience of race-based discrimination may set in motion a chain of physiological events, such as elevated blood pressure and heart rate, that eventually increase the risk of death.

It’s unlikely that the adverse effects of discrimination and bigotry are limited to blacks and whites. For example, community health sciences professor Gilbert Gee and colleagues at UCLA have presented data showing that Asian-Americans who report discrimination are at elevated risk for poorer health, especially for mental health problems.

But are hatred and bigotry contagious?

Supporters of white nationalist Jason Kessler on a subway car after an Aug. 12, 2018 rally in Washington, D.C. Jim Urquhart/Reuters

As the adverse health effects of bigotry have been increasingly recognized, awareness has grown that hateful behaviors and their harmful effects can spread. For example, public health specialist Dr. Izzeldin Abuelaish and family physician Dr. Neil Arya, in an article titled “Hatred – A Public Health Issue,” argue that “Hatred can be conceptualized as an infectious disease, leading to the spread of violence, fear, and ignorance. Hatred is contagious; it can cross barriers and borders.”

Similarly, communications professor Adam G. Klein has studied the “digital hate culture,” and has concluded that “The speed with which online hate travels is breathtaking.”

As an example, Klein recounted a chain of events in which an anti-Semitic story (“Jews Destroying Their Own Graveyards”) appeared in the Daily Stormer, and was quickly followed by a flurry of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories spread by white supremacist David Duke via his podcast.

Consistent with Klein’s work, the Anti-Defamation League recently released a report titled, “New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy.” The report found that,

“Despite the alt right’s move into the physical world, the internet remains its main propaganda vehicle. However, alt right internet propaganda involves more than just Twitter and websites. In 2018, podcasting plays a particularly outsized role in spreading alt right messages to the world.”

To be sure, tracking the spread of hatred is not like tracking the spread of, say, food-borne illness or the flu virus. After all, there is no laboratory test for the presence of hatred or bigotry.

Nevertheless, as a psychiatrist, I find the “hatred contagion hypothesis” entirely plausible. In my field, we see a similar phenomenon in so-called “copycat suicides,” whereby a highly publicized (and often glamorized) suicide appears to incite other vulnerable people to imitate the act.

A public health approach

If hatred and bigotry are indeed both harmful and contagious, how might a public health approach deal with this problem? Drs. Abuelaish and Arya suggest several “primary prevention” strategies, including promoting understanding of the adverse health consequences of hatred; developing emotional self-awareness and conflict resolution skills; creating “immunity” against provocative hate speech; and fostering an understanding of mutual respect and human rights.

In principle, these educational efforts could be incorporated into the curricula of elementary and middle schools. Indeed, the Anti-Defamation League already offers K-12 students in-person training and online resources to combat hatred, bullying, and bigotry. In addition, the Anti-Defamation League report urges an action plan that includes:

Enacting comprehensive hate crime laws in every state.

Improving the federal response to hate crimes.

Expanding training for university administrators, faculty and staff.

Promoting community resilience programming, aimed at understanding and countering extremist hate.

Bigotry may not be a “disease” in the strict medical sense of that term, akin to conditions like AIDS, coronary artery disease or polio. Yet, like alcoholism and substance use disorders, bigotry lends itself to a “disease model.” Indeed, to call bigotry a kind of disease is to invoke more than a metaphor. It is to assert that bigotry and other forms of hatred are correlated with adverse health consequences; and that hatred and bigotry can spread rapidly via social media, podcasts and similar modes of dissemination.

A public health approach to problems such as smoking has shown demonstrable success; for example, anti-tobacco mass media campaigns were partly responsible for changing the American public’s mind about cigarette smoking. Similarly, a public health approach to bigotry, such as the measures recommended by Abuelaish and Arya, will not eliminate hatred, but may at least mitigate the damage hatred can inflict upon society.

RONALD W. PIES is an Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry, Lecturer on Bioethics & Humanities at SUNY Upstate Medical University and a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry atTufts University School of Medicine.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

‘This is Africa’: Depictions of Black People in Mainland China

Earlier this year, Black Panther premiered in theaters around the world. The latest in a string of comic book-themed films turned out to be more of a cultural event than a mere movie. Black Panther broke records in the United States, as well as Great Britain, North and South Korea, and East and West Africa, dispelling the long-held Hollywood myth that “black films don’t travel.” Though fictional, the film struck a chord with audiences, as it featured a predominantly black cast and did not put them into the stereotypical roles often lamented by moviegoers. The film, however, was not as successful in Mainland China. Despite the fact that China is a major trading partner with the African continent, many Chinese moviegoers bristled at the idea of seeing Africans up close.

Chadwick Boseman, star of the movie Black Panther, appearing at Comic-Con in San Diego. Gaga Skidmore. CC BY SA-2.0

China was relatively closed to foreign trade until Deng Xiaoping's economic reform in 1978. Because of this, interactions with non-Chinese people are still a relatively new phenomenon. There is also a traditional standard in China that equates lighter skin with a comfortable, indoor lifestyle, and darker skin with peasantry, having to labor in fields under the hot sun. This combined with exposure to western media creates an environment that can be less than hospitable to blacks. Last year, an exhibit at the Hubei Provincial Museum in Wuhan titled, “This is Africa”, featured a portrait of a young African boy placed next to the portrait of a monkey. The exhibit was visited by over 100,000 people before criticism from the African community prompted museum officials to dismantle it, and the museum curator to take responsibility for the presentation. In February of this year, the same month Black Panther premiered, China’s Central China Television (CCTV) network came under fire when it aired a skit featuring a Chinese actor in blackface. Beijing issued a statement saying it was opposed to racism of any kind, but did not apologize for the skit.

Western nations are by no means immune to racial prejudice. While the Civil Rights movement of the 1960’s attempted to resolve many of the racial schisms that split the United States, lingering prejudices remain in various parts of the country. In recent years, proponents of racism have become more desperate, and less discreet. In January, the president of the United States allegedly referred to El Salvador, Haiti, and various African nations as “shithole countries,” seemingly forgetting his role as chief diplomat. Perceptions of Africa, and by extension those of African descent, are still slanted by the media, and media still accounts for much of the world’s education. This creates a quandary for those who have to live day-to-day under the banner of these stereotypes.

The CCTV building in Beijing. Verdgris. CC BY SA-3.0

There are some things that we believe because it serves us to believe them. Racism today is more than mere ideology. Like sexism, racism has evolved into a cultural standard, feeding into a lifestyle standard that is enjoyed, or not enjoyed, by millions of people around the world. As we begin to tinker with the idea racism, we also tinker with the standards it creates in our societies-some people are bound to get upset. At the same time, this tinkering opens new possibilities for growth, for all the parties it applies to. It refutes old characterizations of people and cultures and encourages us to make connections that we may not have considered before. All change involves a degree of pain and uncertainty, but we can only move forward, confident that the benefits of our efforts will justify the challenges.

JONATHAN ROBINSON is an intern at CATALYST. He is a travel enthusiast always adding new people, places, experiences to his story. He hopes to use writing as a means to connect with others like himself.

Dozens of Migrants Disappear in Mexico as Central American Caravan Pushes Northward

The Hondurans who banded together last month to travel northward to the United States, fleeing gangs, corruption and poverty, were joined by other Central Americans hoping to find safety in numbers on this perilous journey.

Read MoreGreece’s Lifejacket Graveyard

High up in the sunburnt hills of Lesvos, Greece lies a black and orange heap of plastic. It is large, about the size of an Olympic swimming pool, but its vastness pales in comparison to the scope of the reasons why it is there—the half a million and growing masses of displaced refugees who have washed up upon the island’s shores.

Lesvos is a major port for refugees fleeing chaos in the middle east, mostly from war-torn Afghanistan and Syria. The journey across the sea can be deadly. Refugees often pay over $5000 to smugglers who will bring them across the Mediterranean to supposedly safe ports in Europe, but there is no guarantee that the smugglers have not been bribed for one reason or another, or that the journey will be successful.

The black and orange heaps rotting in the hills of Lesvos are made up of lifejackets and boats that belonged to those who made it over, but in those quiet mountains one can almost hear the whispering of the hundreds of thousands who were lost on the way. A closer look reveals children’s floaties, some painted with princess decals, some emblazoned with the message, This is not a flotation device.

Once in Lesvos, the owners of these lifejackets were carted into packed camps, where many of them have remained for years. Conditions in the Moria camp in particular have been widely maligned by human rights organizations around the world. The camp was made to hold 2,000 people and now holds over 6,000, according to official reports, though many believe that the number has exceeded 8,000. Refugees live in cramped makeshift tents that flood when it rains, and the camps are overrun by disease, mental illness stemming from severe trauma, and chaos.

Following the Arab Spring in 2011, which catalyzed revolutions across the Middle East, Syria and many other countries experienced a mass exodus, leading to the flood of people seeking asylum in Europe that has come to be known as the modern refugee crisis.

Many refugees are university-educated professionals, fleeing in hopes of finding a better life for themselves and their families. But once in Europe, they are often caught up in bureaucratic tangles that keep them stagnant in the camps for years at a time, despite the fact that many already have family members in other parts of the continent.

Thousands of volunteers have flocked to the island in order to help. Nonprofits like A Drop in the Ocean host lessons and English classes for refugees, and facilitate the safe landings of newly arrived boats. Others work to provide hygienic services, like the organization Showers for Sisters, which provides safe showers and sanitary products to women and children.

Lesvos itself still functions in part as a tourist town, though it is mostly populated by volunteers, refugees, and locals. Not far from the lifejacket graveyard is the pleasant seaside town of Molyvos, which boasts sandy beaches and restaurants serving traditional Greek fare.

Much of the island is made up of open space, populated only by olive groves and forests, open plains, and abandoned buildings. The lifejacket graveyard is located in one such empty plain, and except for scavenging seagulls and goats, the area is empty, making the presence of the rotting heaps of plastic even more unnerving.

The only other proof of human presence to be found lies on a wall of graffiti nearby a garbage dump, marked by the sentiment Shame on you, Europe.

The combination of the Greek financial crisis and rising tides of nationalism occurring at the same time as the height of the refugee crisis have caused xenophobic sentiments to allow these horrifically overcrowded camps to mar this beautiful tropical island, which once inspired the Greek poet Sappho to write her legendary love poems.

The lifejacket graveyard has been left standing partly because of island officials’ lack of motivation to clean it up, and partly as a statement, a tribute to the thousands who still wait in limbo on the island.

If you are interested in helping out, organizations mostly need financial contributions, legal aid, medical aid, translators, and publicity. It is also possible to volunteer, and opportunities and detailed information can be found at sites like greecevol.info.

Eden Arielle Gordon

Eden Arielle Gordon is a writer, musician, and avid traveler. She attends Barnard College in New York.

SOUTH AFRICA: Dinner in Khayelitsha

South African apartheid is frequently written off as a memory, something that ended decades ago. But from the start of my visit to South Africa, it became clear that the violence of that period has continued to bleed into the present, manifesting itself in clear racial and economic divides.

I visited Cape Town in the summer of 2016. Cape Town is a city of contrasts—tall, imposing mountains cast shadows over clear blue seas, and seaside villas luxuriate only a few miles away from derelict townships.

These townships are the subject of this piece. Townships in South Africa are villages that remain from apartheid-era forced exoduses of non-white people, cast out of their homes and crammed into segregated areas.

These townships still stand today. They are mostly collections of mottled tin-roof shacks and cramped streets, and they are home to 38% of South Africa’s population of 18.7 million.

From the beginning of my arrival in South Africa, I was told by locals that the townships were unsafe, especially for outsiders. But one day, I returned to my flat in the town of Observatory and one of my roommates asked me if I wanted to visit one.

The visit would be hosted, she told me, by Dine With Khayelitsha, a program founded by four young township residents designed to foster communication between their communities and those outside. Dine With Khayelitsha started in March 2015, as part of a partnership with Denmark and Switerland intended on working as a fundraiser. It then grew and has now hosted over 100 dinners. Each dinner is attended by at least one of the founders, who assures the safe transportation of every participant.

Thanks to this organization, I found myself on a bus driving into one of the townships, and then I was suddenly in a house with a bunch of strangers, eating authentic South African beans and meat.

We arrived at the township’s president’s home, though she was not there—she was outside campaigning, and instead several locals were cooking the meal for the night.

I had come with my new friend, and among the other attendees were two Dutch women, an artist from Germany, a couple from France and Morocco, and a South African black woman. Noticeably absent were white native South Africans, a fact that we asked the hosts about. Apparently, South Africans themselves still persistently ostracize the townships, creating divisions between themselves and the poorer underside of their country.

Our hosts were a few young men from the townships. They had all attended college and one worked in IT and another in software engineering, and most of them also ran after school programs such as leadership and self-esteem workshops for township kids. They had started this organization in an effort to generate more dialogue among South Africans and to raise awareness and reduce stigma concerning the townships.

First, they asked us to discuss one act of kindness we’d performed recently. As night fell, the talk began to flow more easily. We discussed the fact that so many kids from townships are forced to go through school and university, if they can make it that far, in order to get menial jobs that can support their families. For these kids, following their dreams is not an option, but it is rather an inconceivable luxury. One of the hosts said that he would love to run education programs for kids, but instead he had to become an engineer to support his family.

After dinner, as we were waiting for a bus to come pick us up, I asked one of the men if most people born into townships grow up wanting to escape, to find better lives. He told me that some did, but in his opinion, it is far more important to stay in the townships and to try to create a better life there. That’s what he had done; he’d gotten an education and a job and still lives in the townships, trying to create programs and to help uplift the state of the community.

I talked to another local who was a writer, and his eyes shone as he talked about how he can capture strange and vivid moments with words—and another who spoke passionately about his desire to hear stories from people all around the world. There was an undercurrent of kindness that seemed to link these people together that I have rarely seen; a desire to include others, to tell stories and to share parts of their lives, to not build walls but to rather create open streams of connection. To create rather than to destroy.

Conversations like this one cannot heal or make up for old wounds inflicted upon non-white people in South Africa—only physical reparations and policy changes can truly begin that process. But they are a step in the right direction—a step towards understanding that we are all part of the same global community, and the walls between us are really made of dust.

EDEN ARIELLE GORDON is a writer, musician, and avid traveler. She attends Barnard College in New York.

"The great aim of education is not knowledge but action." -Herbert Spencer

Health Care Inequalities Impact Indigenous Communities

What are the Effects of Racism In Health Care Delivery in Canada and the US?

Research released the week of July 1 suggested health care inequalities among indigenous communities extended beyond the Northwest Territories’—where around half the population is indigenous—to all of Canada. The research says racism, in particular implicit racism, has contributed to unnecessary deaths among indigenous communities. Dr. Smylie, a Métis doctor and researcher, commented that “the most important and dangerous kinds of racism that people encounter is actually racism that's hidden.”

Yet implicit racism is not new: it has been the focal point of past studies, most notably the 2015 Wellesley Institute study “First Peoples, Second Class Treatment” also led by Dr. Smylie. The study suggested indigenous people either strategized their visits or avoided care completely due to the frequency of experienced racism. Such racism was commonly felt in a “pro-white basis,” according to Dr. Smylie, and negative stereotypes that originated in colonial government policies like segregation.

Michelle Labrecque’s prescription for severe stomach pain was merely a message to not drink (source: CBC news).

The findings of the 2015 Wellesley study underlined the unnecessary death of elder Hugh Papik in 2016. Even though Papik did not have a history of drinking, Papik’s stroke was mistaken for drunkenness. His death prompted an external investigation that made 16 recommendations for the Government of the Northwestern Territories. Four of the recommendations focused specifically on fostering relations between indigenous communities and health care professionals. All but two were adopted.

The recommendations included training staff—“policies for implementation of mandatory and ongoing culture safety training… in partnership with the Indigenous community”—in hopes of breaking down the root issue of systemic racism by confronting stereotypes. According to health minister Glen Abernethy, training will do so by incorporating information about the different cultures of the territory as well as a history of colonization for non-indigenous staff. In addition to the training, Abernethy hopes to increase the number of indigenous staff in the future by encouraging young locals to pursue medical careers so that they might return and serve their communities.

However, the messy entanglement of racism and health care is not unique to Canada. A 2017 survey by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found 23% of Native Americans faced discrimination when “going to [the] doctor or health clinic” in the US.

Even though the US federal government is obligated, through treaty agreements, to provide for the health of Native Americans, the IHS itself is too underfunded to provide adequate care. A 2014 study stated that “Long-term underfunding of the IHS is a contributing factor to AI/AN health disparities.” Indeed, for people like Anna Whiting Sorrell who have struggled to get treatment in the past, it is no surprise that “a lot of American Indians simply put up with …“‘tolerated illness.’” Other care alternatives are also difficult to access as the American health care system makes it hard for many Native Americans to obtain care in the private sector.

Cartoon depicting the waiting room of an IHS facility-- and the struggles of the system (Source: Marty Two Bulls).

And while some communities have successfully started looking inwards at traditional forms of healing and eating to improve health, it is evident that many are doing so because outside systems of support are inadequate or nonexistent. Although Canada is actively trying to address inequalities in its health care, the US has yet to do so.

TERESA NOWALK is a student at the University of Virginia studying anthropology and history. In her free time she loves traveling, volunteering in the Charlottesville community, and listening to other people’s stories. She does not know where her studies will take her, but is certain writing will be a part of whatever the future has in store.

Literacy… for Whom?

The significance of the Gary B. v. Snyder lawsuit dismissal.

Detroit students opened up the conversation on who has the right to education (Source: Steve Neavling).

On June 29, 2018 US District Judge Stephen J. Murphy III dismissed a federal class-action lawsuit, Gary B. v. Snyder. The lawsuit, filed in 2016 by Public Counsel and Sidley Austin LLP on behalf of a class of students, claimed the plaintiffs were deprived of the right to literacy. The decision will be appealed at the US Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Although Judge Murphy agreed a degree of literacy is important for such matters as voting and job searching, he did not say it was fundamental: constitutional. The central reasoning for the dismissal of the case was the suit failed to show overt racial discrimination by the defendants in charge of the Detroit Public Schools: the state of Michigan. The other reasoning Judge Murphy provided was that the 14th amendment’s due process clause does not require Michigan provide “minimally adequate education.”

Meanwhile the case brings up an important question its initial filing gave rise to: is literacy a constitutional right? One could argue the importance of literacy goes back to Reconstruction. According to Professor Derek Black, Southern states had to rewrite their constitutions with an education guarantee in addition to passing the 14th amendment before they could be readmitted into the US. Black states “the explicit right of citizenship in the 14th Amendment included an implicit right to education.”

The theme of education and citizenship is a central component to the complaint’s argument for literacy as a fundamental right. It appeared in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case too, which emphasized that education was “the very foundation of good citizenship.” The complaint drew on this citizenship theme to argue the importance of establishing elementary literacy tools—about the equivalent of a 3rd grade reading level. These can then develop into adolescent literacy skills, which allow an individual to comprehend and engage with words. Such engagement is what democratic citizens need when they are making decisions on who to vote; even more importantly, literacy is essential to understanding the often complex ballots voting requires. Further, literacy allows one to take part in political conversations.

The schools in question also “serve more than 97% children of color,” according to the complaint. Many of these students also come from low income families. On the 2017 Nation’s Report Card the average score out of 500 for reading was 182 for Detroit 4th graders, compared to the national average of 213 in other large city school districts. If the 1982 Pyler v. Doe case argued children could not be denied free public education that is offered to other children within the same state—in line with the 14th amendment—then why the disparity in scores?

The plaintiffs believe the disparity lies in deeply rooted issues in the Detroit Public Schools. They argue literacy tools that are first taught in elementary school are not only unavailable to them but that their schools are also not adequate environments for fostering education.The complaint mentions unsanitary conditions, extreme classroom temperatures, and overcrowded classrooms as environmental stressors. They also mention inadequate classroom materials as well as outdated and overused textbooks.

Worn history textbook from 1998 (source: Public Counsel).

Not only is the school environment not conducive to learning for these students but their teachers are often not the proper facilitators for learning. The complaint mention such issues as high teacher turnover, frequent teacher absences, lack of short term substitute teachers, inadequate teacher training, and allowance of non-certified individuals. The complaint also states students at these schools may also have unaddressed issues related to trauma teachers are not trained for.

And the solution to these discrepancies could very well be what the plaintiffs are arguing for: make literacy, education, a fundamental right. In a 2012 Pearson study on global education systems, the US was number 17. All the countries ahead of the US had either a constitutional guarantee of education or a statue acknowledging the role of education. According to Stephen Lurie, this creates a baseline ruling of what education entails: a culture of education around which laws can form.

Such a baseline ensures education is not a question of privilege. Indeed such conditions as the complaint mentions, as lawyer Mark Rosenbaum stated, would be “unthinkable in schools serving predominantly white, affluent student populations.” What Gary B. v. Sanders is asking for is a safe school environment, trained teachers, and basic instructional materials. It is asking that Detroit students are guaranteed a minimum of education that will at least give them the chance other students in Michigan have at becoming informed citizens and adults.

Teresa Nolwalk

Teresa Nolwalk is a student at the University of Virginia studying anthropology and history. In her free time she loves traveling, volunteering in the Charlottesville community, and listening to other people’s stories. She does not know where her studies will take her, but is certain writing will be a part of whatever the future has in store.

A Refugee-Run Restaurant in Lisbon's Mercardo de Arroios

Mezze: Rebuilding, with Food

In a market as diverse as Lisbon’s Mercado de Arroios, where people from all over the world shop, Mezze doesn’t seem out of the ordinary. But the small restaurant deserves a closer look: it’s not only one of Lisbon’s few Middle Eastern restaurants, but, more importantly, its staff is almost entirely made up of recently arrived Syrian refugees. For them Mezze represents both a link back to the country they left behind and a crucial aid for putting down roots in their new home.

The idea behind Mezze is one that’s being tried out in other countries. Refugees, particularly those fleeing the war in Syria, are given the chance to earn a living and get established by sharing their culinary heritage, either by opening or working at a restaurant or catering business. The benefit is not just for the refugees, who are able to earn some money while at the same time preserving a taste of home, but also for their new communities, who can support those displaced by war and gain insight into their cultural heritage through the universal language of food.

Mezze’s start, though, was motivated by something simpler – the desire for bread. Alaa Alhariri, a 24-year-old Syrian woman who came to Portugal to study architecture in 2014 after a brief time spent studying in Egypt and Istanbul, was missing the flatbread she used to buy back home. “Bread is the beginning of everything, it exists in every culture,” she says. “In the Middle East it means family, it means sharing. Syrians open bakeries as soon as they arrive in Turkey and in other countries as well.”

Alaa is one of the four founders of the non-profit Pão a Pão, which means “Bread by Bread,” a name inspired by the Portuguese saying “Grão a Grão” (“Grain by Grain,” which has a similar meaning to “step by step”). The organization was the brainchild of Alaa and Francisca Gorjão Henriques, another cofounder and Pão a Pão’s current president. Francisca and Alaa met by chance – Alaa was living with Francisca’s aunt. Pão a Pão was originally created with the intention of opening a bakery.

“Refugees [from Syria] started to arrive in Portugal in 2015 under the European Union program to relocate them,” explains Alaa, whose eyes shine with enthusiasm when talking about the project (while she’s heavily involved in behind-the-scenes work, she doesn’t work at the restaurant). “They only receive state assistance for two years, after which the funds stop.” The aim of Pão a Pão is to help young people and women, in particular, integrate into the work force. “Some of these women have never worked before,” says Alaa. “They’ve been housewives all their lives.”

But the team at Pão a Pão began to think bigger; the bakery plan was scrapped and their new aim was to open a restaurant. They organized a series of successful test dinners in December 2016, which took place in an old covered market that had been converted into an events space. Buoyed by the positive response, Pão a Pão felt confident in taking the plunge. They were able to crowdfund just over 23,000 euros (around $30,000) – almost 10,000 euros more than the initial goal – over the course of 2017, with the restaurant finally opening its doors in September, serving such classic Syrian dishes as moussaka, kibbeh (fried balls made of bulgur, minced meat and walnuts), kabseh (rice with vegetables and chicken) and baba ganoush.

“The people working here feel like they’re doing something useful. So the more people we can help feel this way, the better.”

“People’s reactions have been amazing, it is better than we could expect, we’re always busy,” says Francisca, who recently left her job as a journalist at the Público newspaper to concentrate on her work with the organization. “We have improved a lot since our first test dinners, especially considering that 90 percent of the team had no prior experience.”

Mezze has also been extremely well received by the Mercado de Arroios’s neighboring shops and stalls, which supply the restaurant with its ingredients. Everything Mezze cooks with comes from the market except the meat, which is sourced from a halal butcher in Almada, south of Lisbon.

Perhaps more significantly, the refugees employed by Mezze take pride in their work. Serena, a 24-year-old from Palestine who has been living in Lisbon for one year now, loves the atmosphere at the restaurant. But, more importantly for her, she values the chance to show that refugees are the same as everyone else: “We work hard, we love life and want to be part of society as much as anyone.”

While we talk, she welcomes people to the restaurant and explains the menu. “The Portuguese ask a lot of questions because they don’t know these dishes but everyone loves the food,” she says. Although she finds the language difficult, she considers Portugal to be her home now. “It’s my home, where I find myself,” she explains. “It still has traditional a family structure, family bonds, and at the same time, more freedom of movement and speech.”

Rafat Dabah, 21 years old, has been in Portugal for just under two years, after being relocated with his family from Egypt, where they first moved after leaving Syria. “My father had a restaurant in Syria and in the school holidays I would work there with him,” he tells us. “Here in Portugal I worked in a kebab place in a shopping center.” This experience seems to have served him well. He began working as a waiter at Mezze, but is now the restaurant’s manager – he eagerly explains the improvements they have made at the restaurant and the positive feedback they’ve received from diners.

Originally from Damascus, he lives in Lisbon with his younger brother and his mother, who also works at Mezze. His older brother, 24, lives in Turkey. His father died in the war. Living in Loures, a suburb north of Lisbon, Rafat can’t image going back home to Damascus anytime soon. “It’s tough there. Sadly things are still dangerous.”

As for life in Portugal, he doesn’t feel quite at home yet, although it’s getting better. He tells us how he’s enjoying learning so much, including the Portuguese language. “To integrate you need to learn the language, I’ve learned a lot and I’m practicing more now,” he says. “Once I could communicate, life became much easier.”

This isn’t the first time refugees have made Portugal their home. Because of its neutrality during the Second World War, the country saw a large influx of exiles from other European countries as well as North Africa. Likewise, hundreds of thousands fled to Lisbon after the independence of Angola and Mozambique in 1975. More recently, 1,659 refugees took shelter in the country as a result of the Balkan wars in the early 1990s.

In the last two years, 1,507 refugees (mostly Syrians but also some from Iraq and Eritrea) were relocated to Portugal from Greece and Italy, according to the Portuguese Council for Refugees. The Portuguese Government announced recently that they would receive 1,000 more currently residing in Turkey (again, mostly Syrians but also some from other Middle Eastern countries). Although small in number compared to the massive number of refugees being sheltered in the countries bordering Syria, they are being welcomed warmly. The extraordinary success of Mezze speaks to that.

The support of the Portuguese people has been fundamental to the realization of this project, which leads us to wonder if this openness would have been possible, say, even 20 years ago. “Maybe 20 years ago, without social media amplifying this disaster at the gates of Europe, this wouldn’t be possible,” admits Francisca. “At the same time, today’s Lisbon is much more cosmopolitan than it was 20 years ago. Diversity is now a prime feature in some parts of the city, like in the Arroios neighborhood.”

The ongoing support of Lisboetas, many of whom felt a wave of solidarity with the refugees after Europe initially bungled the refugee crisis, has inspired Alaa and her colleagues to think bigger. “We’re thinking of opening another location. The Portuguese love to eat and we’re lucky that they love our food,” says Alaa.

Francisca confirms the plans to open another place. “We’ve developed this project with the hope of replicating it in Lisbon and other cities in the country. We’re still starting out and we want to improve, but we think we might be able to open in other locations in a year. We also hope to expand our current Mezze to include a take-away and catering service.” They also have plans for debates and workshops, with Pão a Pão hosting a conference on integration at Mezze on Friday, January 26.

According to Alaa, the people working at the restaurant “feel happy, they feel like they’re doing something useful. So the more people we can help feel this way, the better.”

This article originally appeared in Culinary Backstreets, which covers the neighborhood food scene and offers small group culinary walks in a dozen cities around the world.

AUTHOR

CÉLIA PEDROSO

Célia, CB’s Lisbon bureau chief, is a freelance journalist, writing mostly about travel and food, and is the co-author of the book "Eat Portugal", winner of a Gourmand World Cookbook Award. Her work can be seen in such publications as The Guardian, Eater, and DestinAsian. In 2014 she started leading food tours in Lisbon through Eat Portugal Food Tours and now does the same with CB. She wrote the Portuguese entries for the book "1001 Restaurants you Must Experience Before you Die" and keeps searching for the best pastéis de nata so you don't have to.

PHOTOGRAPHER

RODRIGO CABRITA

Photographer Rodrigo Cabrita was born in Oeiras, Portugal in 1977. He started his career at the daily newspaper Diário de Notícias in 2001 and has worked at a variety of publications since then. He is now a freelance photographer and takes part regularly in exhibitions. Rodrigo has won several photojournalism awards, most notably the Portuguese Gazeta award. You can see more of his work at his website and his Instagram page.

Yemeni women take part in a sit-in and a protest against the ongoing conflict in the Arab country, outside the UN offices in Sana'a, Yemen, 16 March 2017. EPA/YAHYA ARHAB

How Yemeni Women Are Fighting the War

Since 2015, a Saudi-led coalition has waged war against Shia Houthi forces in Yemen. More than 8,000 people have been killed, and more than 49,000 injured; at least 69% of the population is reportedly in need of humanitarian assistance. Million of Yemenis are facing starvation. Weapons circulation is widespread and uncontrolled: in 2016, a UN report estimated that between 40m to 60m firearms were circulating freely in the country.

The conflict has had a devastating impact on the women of the country. Household breadwinners are usually men; many are fighting, injured or killed. There is an economic crisis in the private sector, and many public sector jobs are no longer paying salaries. The health and security of the female population is endangered by exposure to cholera and other diseases. And then there’s the issue of child marriages: the severe poverty crisis means that prepubescent girls are married off to repay debts, or to raise funds to feed the rest of the family.

A woman from the Northern Ibb region, which is occupied by the rebel Houthi army, explained the situation to a research team:

We live in a state of lawlessness: no security, no protection and no functional law enforcement authorities. A person may be shot dead for a trivial thing. The security situation doesn’t look like it did in the past. Now, there are informal groups behaving as if they were law enforcement authorities. These groups have power, and their power is the law. They use force against whoever disagrees with them or criticises their behaviour.

As the feminist scholar Cynthia Enloe has pointed out, women are crucial for war and play supportive roles for the military. Indeed, many Yemeni women are not victims of war or just escaping or hiding from this war. In many contrasting ways, they are actively supporting it, and not only on humanitarian grounds.

Women engaging in war

Although many Yemeni women discourage their family members from taking part in the conflict and very few take up arms themselves, they also help recruit men to the army. They also support combatants by cooking food for them and helping to distribute it.

A young woman, Nasseem Al-Odaini, whose family has fled to the neighbouring Ibb region, stayed behind in Houthi-occupied Taiz and initiated an organisation that assist the combatants that support the former government. As she told Middle East Eye: “We want to encourage the pro-government forces to advance in the province, by raising the spirits of the fighters”.

Other Yemeni women try to mitigate the impact of the conflict the best way possible. For example, women engage in humanitarian relief and in providing social and psychological support for people who have been traumatised by the war. They also engage in peace processes when they initiate discussions of the conflict in their communities.

Since the war is not equally intense in every part of the country, there are better possibilities for women to participate in peace processes around the port city of Aden, in the south, than it is in the north, where the Houthi army has taken control and Saudi coalition airstrikes are part of everyday life. Accordingly, women’s conditions and activities differ from one region to another.

Yemeni women and girls wait to receive free bread provided by a charity bakery during a severe shortage of food in Sana'a, Yemen, 15 August 2017. EPA/YAHYA ARHAB

A blocked momentum

In the north, local communities are more divided (between supporters and adversaries of the Houthi government) than in the south. When women enter the public and participate in charity work, they may be questioned by “de facto authorities” (read: the Houthi army) who, according to one woman, would try to prevent them from doing their work. They would also tell women that they are not allowed to appear in public before men:

They [the Houthis] are opposed to women playing a role in public life. According to them, the woman’s role is restricted to cooking and housework. They marginalise women; they deny their role in the community.

Women in Northern and Southern parts of Yemen are not full citizens. According to Amnesty International, they “face discrimination in matters of marriage, divorce, inheritance, and child custody, and the state fails to take adequate measures to prevent, investigate, and punish domestic violence”. Discrimination against women in Yemen go back far beyond the war and are associated with local customs according to several studies. And yet, Yemeni women maintain their engagement in the development of their country.

An old engagement

During the popular uprising in the country in 2011 where hundreds of thousands of Yemenis followed the “youth movement” and protested against the corrupt reign of the then-president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yemeni women took to the streets to an extent that was unforeseen and unprecedented.

Many women participants were independent of political groups, but in the later stages of the protests the Islamic Reform party – inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood – managed to take charge of the protest movement, raising independent women’s concern that their rights would be disregarded.

However, independent women and women belonging to the political parties, including the Islamic Reform party and the Houthi political wing, Ansar Allah, constituted almost one third of participantsin the UN-guided National Dialogue Conference which followed the forced resignation of the President in November 2011. The aim of the 10 months long conference was to formulate a new and more democratic constitution for a united Yemen. However, the draft constitution which included a general 30% gender quota was rejected by the Houthi movement in September 2014, before the population had given their voice in a referendum.

By then disappointment with the process towards a new Yemen had given the Houthis wide popular support. They occupied major government institutions in the capital, Sana'a and removed the transition government recognised internationally. Interestingly, it was not the gender quota which made the Houthis reject the draft constitution, but the view to a power-sharing model which did not give them what they expected.

The Houthi movement’s occupation of the capital and seizure of government seemed to mark both the beginning of a war, and the end of momentum for women’s rights in Yemen – a country which generally figures in the lowest ranks of Arab gender equality indexes. In 2014, a group of women from diverse political backgrounds pushed for political solutions instead of war. Since then they have been sidelined from peace negotiations – but that doesn’t mean that Yemeni women have lost all hope.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

CONNIE CHRISTIANSEN

Dr. Connie Carøe Christiansen is a visiting associate professor in Gender Studies. She was an associate professor at Roskilde University in Denmark and a senior advisor at KVINFO, the Danish Centre for Research and Information on Gender, Equality and Diversity, where she managed academic programs in the Arab region, including a program which established an M.A. program on International Development and Gender at Sanaa University in Yemen. She has published research on gender, migration and Islam in Denmark, Turkey, Morocco and Yemen. She has her M.A. in Cultural Sociology and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Copenhagen University, Denmark.

Climate Change Will Displace Millions in Coming Decades: Nations Should Prepare Now to Help Them

Wildfires tearing across Southern California have forced thousands of residents to evacuate from their homes. Even more people fled ahead of the hurricanes that slammed into Texas and Florida earlier this year, jamming highways and filling hotels. A viral social media post showed a flight-radar picture of people trying to escape Florida and posed a provocative question: What if the adjoining states were countries and didn’t grant escaping migrants refuge?

By the middle of this century, experts estimate that climate change is likely to displace between 150 and 300 million people. If this group formed a country, it would be the fourth-largest in the world, with a population nearly as large as that of the United States.

Yet neither individual countries nor the global community are completely prepared to support a whole new class of “climate migrants.” As a physician and public health researcher in India, I learned the value of surveillance and early warning systems for managing infectious disease outbreaks. Based on my current research on health impacts of heat waves in developing countries, I believe much needs to be done at the national, regional and global level to deal with climate migrants.

The U.S. government is spending US$48 million to relocate residents of Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, because their land is sinking.

Millions displaced yearly

Climate migration is already happening. Every year desertification in Mexico’s drylands forces 700,000 people to relocate. Cyclones have displaced thousands from Tuvalu in the South Pacific and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. Experts agree that a prolonged drought may have catalyzed Syria’s civil war and resulting migration.

Between 2008 and 2015, an average of 26.4 million people per year were displaced by climate- or weather-related disasters, according to the United Nations. And the science of climate change indicates that these trends are likely to get worse. With each one-degree increase in temperature, the air’s moisture-carrying capacity increases by 7 percent, fueling increasingly severe storms. Sea levels may rise by as much as three feet by the year 2100, submerging coastal areas and inhabited islands.

The Pacific islands are extremely vulnerable, as are more than 410 U.S. cities and others around the globe, including Amsterdam, Hamburg, Lisbon and Mumbai. Rising temperatures could make parts of west Asia inhospitable to human life. On the same day that Hurricane Irma roared over Florida in September, heavy rains on the other side of the world submerged one-third of Bangladesh and eastern parts of India, killing thousands.

Climate change will affect most everyone on the planet to some degree, but poor people in developing nations will be affected most severely. Extreme weather events and tropical diseases wreak the heaviest damage in these regions. Undernourished people who have few resources and inadequate housing are especially at risk and likely to be displaced.

Recognize and plan for climate migrants now

Today the global community has not universally acknowledged the existence of climate migrants, much less agreed on how to define them. According to international refugee law, climate migrants are not legally considered refugees. Therefore, they have none of the protections officially accorded to refugees, who are technically defined as people fleeing persecution. No global agreements exist to help millions of people who are displaced by natural disasters every year.

Refugees’ rights, and nations’ legal obligation to defend them, were first defined under the 1951 Refugee Convention, which was expanded in 1967. This work took place well before it was apparent that climate change would become a major force driving migrations and creating refugee crises.

Under the convention, a refugee is defined as someone “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” The convention legally binds nations to provide access to courts, identity papers and travel documents, and to offer possible naturalization. It also bars discriminating against refugees, penalizing them, expelling them or forcibly returning them to their countries of origin. Refugees are entitled to practice their religions, attain education and access public assistance.

In my view, governments and organizations such as the United Nations should consider modifying international law to provide legal status to environmental refugees and establish protections and rights for them. Reforms could factor in the concept of “climate justice,” the notion that climate change is an ethical and social concern. After all, richer countries have contributed the most to cause warming, while poor countries will bear the most disastrous consequences.

Some observers have suggested that countries that bear major responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions should take in more refugees. Alternatively, the world’s largest carbon polluters could contribute to a fund that would pay for refugee care and resettlement for those temporarily and permanently displaced.

The Paris climate agreement does not mention climate refugees. However, there have been some consultations and initiatives by various organizations and governments. They include efforts to create a climate change displacement coordination facility and a U.N. Special Rapporteuron Human Rights and Climate Change.

It is tough to define a climate refugee or migrant. This could be one of the biggest challenges in developing policies.

As history has shown, destination countries respond to waves of migration in various ways, ranging from welcoming immigrants to placing them in detention camps or denying them assistance. Some countries may be selective in whom they allow in, favoring only the young and productive while leaving children, the elderly and infirm behind. A guiding global policy could help prevent confusion and outline some minimum standards.

Short-term actions

Negotiating international agreements on these issues could take many years. For now, major G20 powers such as the United States, the European Union, China, Russia, India, Canada, Australia and Brazil should consider intermediate steps. The United States could offer temporary protected status to climate migrants who are already on its soil. Government aid programs and nongovernment organizations should ramp up support to refugee relief organizations and ensure that aid reaches refugees from climate disasters.

In addition, all countries that have not signed the United Nations refugee conventions could consider joining them. This includes many developing countries in South Asia and the Middle East that are highly vulnerable to climate change and that already have large refugee populations. Since most of the affected people in these countries will likely move to neighboring nations, it is crucial that all countries in these regions abide by a common set of policies for handling and assisting refugees.

The scale of this challenge is unlike anything humanity has ever faced. By midcentury, climate change is likely to uproot far more people than World War II, which displaced some 60 million across Europe, or the Partition of India, which affected approximately 15 million. The migration crisis that has gripped Europe since 2015 has involved something over one million refugees and migrants. It is daunting to envision much larger flows of people, but that is why the global community should start doing so now.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

GULREZ SHAH AZHAR

Gulrez Shah Azhar is a doctoral candidate at the Pardee RAND Graduate School and an Assistant Policy Researcher at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica. His dissertation, "Indian Summer: Three Essays on Heatwave Vulnerability, Estimation and Adaptation," focuses on health impacts of heat waves in developing countries.

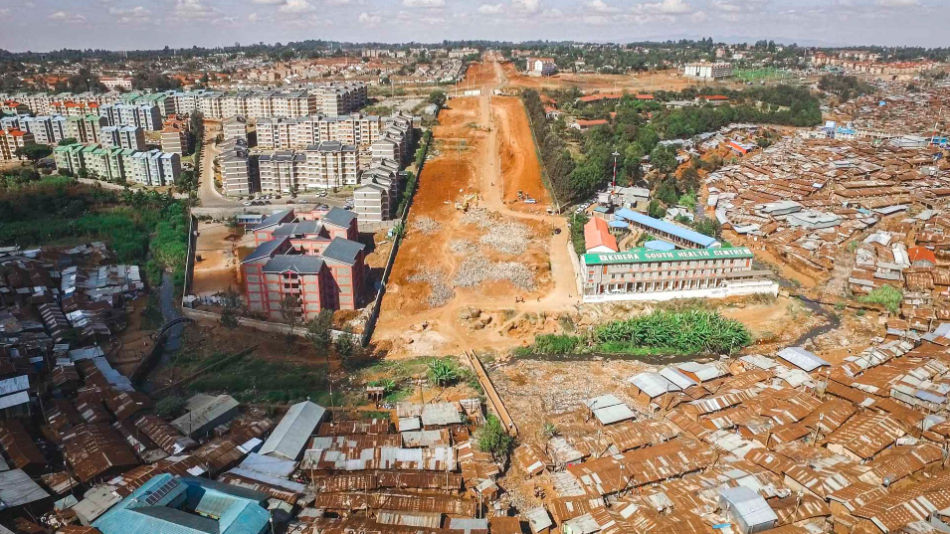

Upwardly mobile Kenyans live in planned, gated communities. Sometimes these abut the poorest of slum communities, this one in Loresho.

Unequal Scenes: Nairobi

“It has been estimated that the richest 10 percent of the population of Nairobi accrues 45.2 percent of income, and the poorest 10 percent only 1.6 percent,” according to a 2009 study on urban poverty by Oxfam.

Statistics on inequality and poverty are ubiquitous in the developing world. They are often underwhelming, however, in their impact. What does 45.2 of income look like? What does “urban poverty” look like? As, of course, every statistic is relative.

The Royal Nairobi Golf Club sits directly adjacent to Kibera slum. Twice a day, a passenger train barrels through the slum, less than a meter away from people's homes and businesses. Next door, people play the game surrounded by greenery.

In Nairobi, a city of chaos, dynamism, and incredible unequal growth, this is even more difficult to portray. Yes, it has easily the poorest urban slums I’ve ever visited. In Kibera, a hilly community, every drainage is choked with tons of raw sewage and rubbish. Children play on live train tracks, running through the middle of the slum. Government services, aside from electricity, are nonexistent. The houses are made from a mixture of mud, sticks, and tin.

But also, yes, the wealthy parts of Nairobi are more difficult to see. They are hidden behind gated communities, ensconced in shopping malls, or wrapped in dingy-looking apartment buildings. Moreover, researching these inequalities is made difficult by the lack of searchable data sets, a draconian drone flying environment, and Nairobi’s infamous traffic problems.

Kibera is constrained not only by infrastructure but also the natural environment. The "river" at the bottom of the slum drains thousands of tons of rubbish into the Nairobi Dam every year.

The Unequal Scenes I have found in Nairobi are a mixture of traditional “rich vs. poor” housing images, but also depictions of how infrastructure constrains, divides, and facilitates city growth, almost always at the expense of the poorest classes. During my time there, I focused on a planned road that will bisect Kibera, Nairobi’s largest slum. This road will cut the slum neatly in two, displacing thousands of people, and tens of schools and clinics that are in its way. This road will help alleviate the city’s traffic problem, but it may cause more problems than it will solve. Just to the south, a new road has already cut off part of Kibera, causing people to cross it illegally, resulting in many deaths. From interviews with residents, it is unclear whether or not the planned infrastructure upgrades have adequately taken into account the public opinion.

This dynamism contributes to make Nairobi one of the most fascinating cities I’ve ever been to.

Read more at http://www.thisisplace.org/shorthand/slumscapes/#nairobi-48752

The Southern Bypass road has already lopped a portion off of Kibera, in the quixotic search for a less congested city. Although there is an underpass (visible at the bottom), people often cross the road from above, resulting in many accidents.

A planned road will bisect Kibera slum in Nairobi, displacing thousands of people.

The Southern Bypass road follows the contours of the river and slum next to it. In the distance, you can see the construction beginning on the new road, which will connect Ngong Rd to Langata Rd.

Cars glide over the brand new road, above the slum below.

The suburb of Loresho is home to the wealthy and the poor alike.

As in many places around the world, the rich and poor are separated by only a thin concrete barrier. But it represents much more than that.

These barriers, whether concrete or imaginary, represent an entire class separation, one that may not be surmounted for generations to come.

Amazing geometric patterns emerge from the air. "Straight" lines become slightly curved.

The train is a part of life to Kibera, a source of transportation, of annoyance, of time passing.

The chaos, noise, and density of the slum is neatly juxtaposed with the orderly calm green of the Royal Nairobi Golf Club, which opened in 1906.

THIS ARTICLE AND PHOTO SERIES WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON UNEQUAL SCENES.

JOHNNY MILLER

Johnny Miller is a freelance documentary photographer and filmmaker based in Cape Town, South Africa. His 'Unequal Scences' project is meant to show the stark inequality seen in South Africa and in cities around the world. Check out his website and Facebook to find out more.

For LGBTI Employees, Working Overseas Can Be a Lonely, Frustrating and Even Dangerous Experience

As the number of workers taking international assignments increases, companies have more responsibility to look after their LGBTI employees who face persecution while on assignment.

Russia, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia are becoming some of the most challenging expatriate assignment destinations for multinational firms, according to relocation business BGRS. This is in part because some of these countries advocate the death penalty for homosexuality. Other popular assignment destinations include Brazil, India, China, Mexico and Turkey, and these countries exhibit less sensitivity to homosexuality.

International assignments among multinational corporations have increased by 25% since 2000 and the number is expected to reach more than 50% growth through 2020.