Christopher Rehange walked through China for one year, 4500 km. He let his hair grow and had many adventures along the way.

Read MoreGHANA: Child Slavery

One small boy. One huge lake. Foli was a slave. Immerse yourself in his story.

Thousands of children between the ages of 6 and 18 live in slavery on Lake Volta, working up to 18 hours a day in the fishing industry. For these young children, the only way out of slavery is to drown or be rescued. Children just like Foli.* Visit ijm.org/foli to send rescue today.

African Journals | Chronicles from the Road, Part Two: Portraits

The thing with photographing portraits is, it’s almost the opposite of what we are used to. We, as photographers, are always looking to capture the moments in between; the spontaneous moments, trying to be as invisible as possible to get the shot while no one is aware of the camera. A game of cat and mouse. Shooting portraits is a whole different story to us. We are emotional-shooters; we can not just go out on the streets to shoot portraits of people we don’t know. It feels like you’re stealing someone’s identity, to use it for your own gain. That doesn’t work for us. We have to have a connection with someone to get so close, to take a photograph of someone on a personal level. They are part of the picture and it’s their story, after all. We make portraits to share that story.

We met a lot of people randomly; asking for directions, on the road, in a bar, in the supermarket, in a queue, at a party, via other new friends or just by coincidence. You cannot choose those moments, it happens to you unannounced, as long as you are open to it.

Here, we will share a few highlights of the encounters we had.

Daniel Maluleka

We met Daniel while he was working at the Blacksheep, an amazing restaurant in Cape Town.

Born and raised in Kwazulu-Natal, he moved to Cape town to chase his dreams. He studied economics and journalism and loves music festivals. One of the most energetic, sparkling and happy people who ever crossed our path. His personality is so strong. The click was enormous and we had a lot of fun. He told us about his biggest dream, to work on a Yacht in The South of France. He got all his papers and saved money for a long time. He is there right now, and we will meet again in Amsterdam this summer. We can’t believe it.

Koy & Tatadoe

Along the C14 (read about it here) from Walvisbay to Sossusvlei, when you first enter what could well be the film-set of The Lord of the Rings, after hours of sandy desert, you will pass the first sign of civilisation in its purest form. In the middle of these wide stretches, green landscapes with purple grey mountains peeping out of the horizon, there was a tinned house which caught our eye. Two black guys were sitting out front waving at us. A moment later, we were having a chat. We got some cold beers from the back of our car, and we were talking about wild animals. They knew exactly where a zebra family was at that very moment; their job was to keep an eye on the wildlife and nature. They came from Rwanda, couldn’t find a job after high school, and somehow they ended up here. They work for a German woman. They are 20 and 22 and eat porridge 3 times a day and the closest shop is 40km away. It was so special to meet them. Three days later, we drove 40km back with a surprise box full of food, drinks, beers and a letter. We thanked them for being who they are.

Kids of Zambia and Tsakane

And then there were kids. Lots of kids. Two amazing projects came along on our trip. The first one is The Zambezi Sunshine Trust project in Zambia. Our local friend, Herbert, told us about his wife’s school – the Nakacheya Primary School, set up thanks to the Zambezi Sunshine Trust Project. We got the opportunity to meet the children and we spent some time at the little school, where they teach and feed 300 children every day, with no electricity or running water. The Sithandi’Zingane care project in Tsakane is the second one. We visited them for three days and worked in the kitchen with the local people to prepare breakfast and lunch for over 500 children, it was an honour to be there and to get to know the people and children.

At both places the children were dancing, laughing, jumping around. So cheerful and full of energy. It was touching. It’s always emotional to take portraits of children, because they are just so pure. They also have no prejudice at all. It really does something to me.

Because Africa gave us more than we could have imagined, we wanted to give back. We organised a fundraising exhibition in our hometown, Breda, and sold 80 portraits! All the profit will go to the Zambezi Sunshine Trust project in Zambia and to the Sithandi’Zingane project in Tsakane, Johannesburg. We are now in the process of organising a second addition.

The Zambezi Sunshine Trust project:

http://www.zambezisunrisetrust.co.uk/projects/

Sithandi’I Zingane Care project:

http://www.sithandizingane.co.za/

We will never forget the people we met.

The most important thing when meeting new local people is to be open-minded and to adjust. Show your respect at all times. It doesn’t matter where you are from, who you are, or what you are doing; have real conversations that really matter. Be open to every kind of conversation, from small-talk to serious subjects. And just be yourself, don’t act differently. You will feel a connection sooner or later. And remember, you can’t be friends with everyone. That’s a fact, all over the world. We loved every conversation we had and we couldn’t get enough of the stories. And they love to hear yours too.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON ROAM MAGAZINE.

MANOUK QUINT

Manouk Robina Quint is a 25 year-old photographer currently living in Amsterdam. She has loved creating stories for as long as she can remember. Manouk now has her own photography business; Hans en Grietje – donotsaycheese.com. Together with her soulmate, Hidde van der Linden, they began by capturing the party-life of Amsterdam in clubs, parties and festivals. Now the duo photograph food, interior, fashion, weddings, portraits and travel, also writing concepts and stories to create campaigns for brands.

Follow Manouk on Instagram or visit her website here.

Inside Haidary’s cafe, a female barista poses next to the coffee maker on March 19, 2017.Photos by Ivan Flores

The Unlikely Industry Empowering Women in Afghanistan

The typical depiction of an Afghan woman looks like this: Timid and fearful, she is a victim of her extremely conservative and regressive society, unable to move around or do much without a man. But some Afghan women are busting these stereotypes, creating a niche for women to empower themselves and change the status quo.

A 36-year-old restaurant owner named Laila Haidary walks around the cafe gardens, carefully tending to the colorful foliage that grows generously around Kabul. She narrates her story of building a business in Afghanistan, a country governed by the rules of men. Overlooking the gardens is a midsize structure: a traditional Afghan house, with thick walls, large windows, and ample courtyard space, converted to a cozy restaurant with old tables and chairs and plenty of handmade rugs. The vibe is welcoming.

Haidary explains she wanted to provide a social space for artists and other young Afghans who want to interact with their culture and rich heritage. “This idea in itself had its own challenges because our extremely conservative society does not always approve of artistic expressions. Added to that, the fact it is run by a businesswoman makes many people uncomfortable,” she says.

Haidary’s cafe is among the many newer restaurants in Kabul, and around Afghanistan, that are either owned or managed by women in an otherwise male-dominated industry. Although data measuring this trend wasn’t available at the time of publishing, anecdotally, more women are entering the service industry: Within a two-block radius of my home in Kabul, I can count seven restaurants that have come up in the past year; that wasn’t the case in 2014, when I first came here.

Of course, not every woman in the industry is a business owner. A small but significant number of Afghan women are working jobs in the service sector—a profile that was unimaginable for Afghan women a decade ago and is still considered inappropriate.

“I feel like I’m breaking stereotypes every day by just being here. That makes me feel very proud of myself,” says 20-year-old Mujda Nasiri, who started working at 50/50, a local fast-food restaurant in Kabul, about a year ago. “Initially, my parents were reluctant, but now that they see how independent I have become, financially and personally, they’re happy for me,” she says, adding that she had always been fascinated by the restaurant industry.

In a deeply conservative society such as Afghanistan, women have few avenues to pursue careers. Many of the jobs available—such as manual labor, technical positions, and banking and finance—are not considered suitable for women because traditionally a woman’s priority has been with her family and, especially, their honor. Added to that are the decades of war that have left the Afghan economy enormously dependent on foreign aid, thereby increasing unemployment and competition in the markets. As the rate of unemployment peaked at 40 percent in 2015, it has been even more challenging for women to be considered for jobs in a market that tends to favor men.

Women smoke inside Laila Haidary's restaurant on March 13 2017 in Kabul, Afghanistan. Smoking is considered a taboo for women, especially in public.

However, restaurants such as 50/50, which strives to be an equal opportunity employer, hires several women in various positions. “We are trying to create an all-inclusive space for our customers, especially for women and families, who can come here without any fear of harassment. Such a place is also good for women to work at,” explains Zahir, 37, the restaurant manager at 50/50 (most Afghans traditionally go by just one name). “We also find that women employees are more professional, timely, and able to work with grace despite pressures—a right fit for this industry.”

Nasiri is one of three waitresses the restaurant hired last year, and the move was welcomed by many of their customers. “I’ve had a very good experience working here; my colleagues are like my family and are very protective of my safety,” she says, recalling an incident where a displeased customer lectured her about how inappropriate such a job was for a woman.

“But I see that there has been a change in attitudes,” Nasiri says. “I find that a lot of our customers are not only happy to see me serve them, but [are] also very encouraging of my work. This one elderly gentleman was so happy to meet a working woman, that he left me a Afs1000 [$15] tip to keep me motivated,” she says, adding that the joy of meeting new people every day is a bigger motivation than money to stay with this job.

Twenty-five-year-old Nikbhakt, a barista at a local coffee shop frequented by the many foreigners and expats in Kabul, would agree with Nasiri. “I’ve been making and serving coffee for the last four years, and the best part of my job is interacting with people from around the world,” she says. There was a time when an Afghan woman couldn’t leave the house without a mahram—a male escort who is a blood relative—let alone talk to other people. Women had few places to engage socially in the extremely conservative and patriarchal society under the Taliban regime in the late 1990s.

Parents have reason to be concerned about their working daughters. Harassment at work and in public is a common sight in Kabul and other Afghan cities. Afghan women have to fight many gender stereotypes and inequalities along with abuse if they choose to pursue a career, any career. As a result, many women prefer jobs that require less mobility because even the act of traveling to work daily can often subject women to street harassment. Added to this the rising insecurity further discourages families from allowing their daughters to go to work.

Last year, the cafe where Nikbhakt works was attacked, and she barely missed the explosion that claimed the lives of two people, including the cafe’s guard. “I was extremely depressed for a long time after that attack. My family didn’t want me to work anymore, and I didn’t want to step out of home, either,” she says. “But now I know that cutting myself from the world isn’t a solution, and decided to come back to work two months ago.”

Since no institutes offer training to work in the service sector, Afghans have to learn on the job, which can be tedious for the employers. “We’ve had to let two of our female staff go because they were unable to cope with the pressure of working in a restaurant, but that isn’t to say that women can’t work in this industry,” Zahir says. “The environment, of course, matters, and it is perhaps up to us as employers to help create working environments that allow women to work comfortably and to their full potential.”

Women customers are drawn to restaurants where women work. “Having women around the restaurant creates a comforting and calm environment that eventually attracts a wide diversity of customers,” says Haidary, who also employs several women as servers, managers, and cooks.

She started her cafe as a way to fund her other initiative: the Mother Camp, a nonprofit drug rehabilitation shelter she opened seven years ago for homeless addicts in Kabul. When the funding to the shelter started to dry up (few in Afghanistan consider donating to rehabilitating drug addicts), Haidary and her volunteers came up with the idea of establishing this cafe. Even today, most of her employees are former or recovering addicts from the Camp, which also continues to help hundreds of Afghans recover every year.

Laila Haidary sits at one of the tables in her restaurant in Kabul, Afghanistan, 2017.

Haidary has been successful as a restaurateur, but the ride hasn’t been smooth. On the contrary, she faced several threats and intimidations, sometimes even from her own customers who would show up drunk or high on hashish to her cafe, breaking her one cardinal rule—no drugs, no alcohol.

Terrorized but not afraid, Haidary would often take these men head-on. “There was a time when she literally pounced on a large Afghan man who was a guard to a local parliamentarian,” recalls a regular customer at Taj Begum who witnessed the attack. “He had come drunk to the cafe, gotten into a brawl, and threatened to have [Haidary] shut down. When [she] protested, and had him kicked out of the cafe, he smashed her car windows.”

Despite that chaos, Haidary persisted because she wanted to be an inspiration to other women in Afghanistan. “Even when the going got tough, I didn’t quit. Not only did I need this to support Mother Camp, but I also wanted to show to our society that a woman can run a successful business,” she says.

The social change, however, will have to be gradual, and Afghan society will need more time to accept working women, especially in the service sector, as a norm. That said, women have come by leaps and bounds, having survived many wars and the brutal and patriarchal Taliban regime, during which they couldn’t even step out of their homes without male escorts. They know they’re more than just victims—they’re survivors who are overcoming odds, every day.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON YES MAGAZINE.

RUCHI KUMAR

Ruchi is an Indian journalist based in Afghanistan covering developmental, cultural, and political stories from the region.

One Hong Kong Minute

This quick video shows what goes on in a fast-pace city. Through both rapid timelapses and regular shots, see the constant movement of Hong Kong and its people in just an ordinary day.

Untouchable Beauty | The Gypsies of Tamil Nadu

I had heard of the Narikuravar, and even seen their camps sprawled out across pavements in the city, lending significance to their reputation as Gypsies. I was told their living conditions were appalling and to be aware of begging. As my local friend and I pulled up to one such settlement on the outskirts of Tiruvanamalai at 7am, plumes of smoke were already rising from earthen hearths and curious children began to appear from all directions. Soon, tiny hands were holding mine and dragging me down the sweltering lanes from one thatched hut to another.

Though I was in the heartland of conservative Tamil Nadu, these pre-pubescent daughters often wore lipstick, eye-shadow, and fake diamonds. The famed beauty of Gypsies is indeed jaw-dropping, and a touch out of place for the conditions in which they subsist. Girls seem to understand their charm and perhaps for a community whose females barely ever make it to middle school, it is not surprising that they flaunt the features which will attract a male suitor.

Although it is officially illegal in India, the Narikuravar still practice child marriage. Half of the female population are illiterate and spend their days making beaded ornaments or plastic flowers to be sold in markets by their husbands. They are incredible dancers. Their gaze can pierce your soul. And by the time a young woman is in her twenties, she has an abundance of little ones to look after.

Sadly, this is the same old story for so many marginalized and stigmatized communities.

The Narikuravar are considered ‘Untouchables’, India’s lowest caste, and this label has pitted them against a modernizing world in which they can stake no claim.

Education is undoubtedly the means to break the insidious stranglehold of superstition and backward thinking that too soon turns starry-eyed girls into weathered mothers. However, young women of the Narikuravar are equally oppressed by the archaic beliefs of elders, who think that education will corrupt a girl by empowering her to question her circumstances. After all, who will stand in the hot sun each day to fill jugs with water?

Written on the faces of these young ladies is a sort of ‘who cares’ expression, but when pressed about going to school, their rebellious attitudes prove to be as flimsy as the thatched huts they live in. It seems that their resistance to development is actually resignation to an unavoidable fate. For an Untouchable girl the future is a predictable one. By mid-life, the lines etched across a woman’s face tells the story that lips do not have to.

Yamuna Flaherty is a photographer and writer interested in tribal communities and is currently working on a project to dig a well for this Narikuravar village. www.youcaring.com/letsbuildawell

Check out Yamuna’s website or follow her on Instagram for more stunning photography and stories.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON ROAM MAGAZINE.

YAMINA FLAHERTY

Yamuna Flaherty is a multi-disciplinary storyteller, published author, and explorer who has spent the last 17 years on a global pilgrimage. Her photographic and literary work often explores the intersection between consciousness, culture, and identity. She is a regular traveler to India and has matrilineal roots in Tamil Nadu.

Improving Lives With Fair Trade

More than 40 million people work in the garment industry worldwide. As some of the world’s lowest paid workers, they are at the mercy of a system in which many companies strive to maximize profits by paying employees as little as possible.

Read MoreAfrican Journals | Chronicles from the Road, Part One: Landscapes

The road trip started in Cape town were we spent a month shooting a campaign for Fayrouz, a product by Heineken. From there we had no plan, but by meeting locals, listening to their stories and being open-minded about every adventure we came across, we ended up in Windhoek, Namibia with a 4×4 monster truck which we called Bowser (super Mario kart). The route formed by itself, in a natural way. We got invited to shoot photos for lodges, guesthouses and hotels in Otjiwarongo, Swakopmund, Walvisbay, Rietoog and then we continued on our way to Sossusvlei. There is a big German influence visible in the cities/villages, especially on the Skeleton Coast. You will find Bratwurst on the menu, for sure. Namibia was a German colony until 1904. The route from Walvisbay to Sossusvlei – the C14 – was insane, unforgettable. It is supposed to be a four hour journey, but it took us seven. After hours of sand and drought, something magical happens… You drive through this big mountain, and afterwards you’re suddenly driving through green and purple landscapes – so unreal, like you’ve arrived on the film set of The Lord of The Rings. All the way to the red dunes of Sossusvlei there is so much wildlife to see, and you only pass through one ‘village’ Solitaire. I say ‘village’, but it is really just a petrol station where you can eat apple pie with the few local people who live there. It is amazing. Sossusvlei is like the cherry on the cake; from 6am the colours are changing like the wind. Incredible.

Next stop: Victoria Falls. One of the Seven World Wonders. We arrived in Zimbabwe, but our accommodation was in Zambia (the Falls are on the border between the two countries). Zambia was such a surprise; rainforest, monkeys everywhere, snakes and the best local market – the Maramba Market – where you can meet local people, have fun, and drink cheap local beer, Mozi beer! You can easily spend a whole day at Billy’s Café, listening to stories, playing pool and enjoying local goods like cassava pate (pretty weird stuff to be honest). The music is loud and everyone will dance the day away.

From Zambia to Botswana involves taking a lot of different public transfers, ending up at the border where you take an Industrial-Truck-Ferry. Trucks wait in line – sometimes for more than two weeks! – as the ferry can only carry one truck at a time, with a bunch of people around it. In Botswana, the public bus trips were epic. From Kasane to Maun (18 hours), from Maun to Gaborone (14 hours) from Gaborone to Jo’burg (15 hours). It was the rainy season and a lot of roads where flooded.

Jo’burg was our last stop. This city made a deep deep impression on us. It was so electric, in a lot of ways. You feel the different layers of the city from the past, but you also feel new energies. There is a lot happening, the city with all her different areas is very dynamic and moving. It’s hard to explain the way we feel about this city, we would recommend everyone to go there, to experience it in your own way.

Showing respect and interest in local people is so important. We met interesting people everyday and it was a real honour to hear their voices, their stories and to have chats about the little things in life too. The city center is not the nicest place to go at the moment, but there are a lot of upcoming areas like Maboneng (meaning ‘Place of Light’), Melville, Braamfontein, Fox Precinct and Newtown.

This city brought us a lot, we were really inspired by the people, the vibe and also the deep history that this city is carrying. BBC describes how Johannesburg has changed from a ‘no-go to gotta-go’ – that says a lot. Things are changing, but like all important world changes, it takes time.

See you soon dear Africa, you are in our hearts.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON ROAM MAGAZINE.

MANOUK QUINT

Manouk Robina Quint is a 25 year-old photographer currently living in Amsterdam. She has loved creating stories for as long as she can remember. Manouk now has her own photography business; Hans en Grietje – donotsaycheese.com. Together with her soulmate, Hidde van der Linden, they began by capturing the party-life of Amsterdam in clubs, parties and festivals. Now the duo photograph food, interior, fashion, weddings, portraits and travel, also writing concepts and stories to create campaigns for brands.

PERU: Home at Dawn

Fisherman Fredy Guardia has been catching the main ingredient in Peruvian ceviche for more than 60 years. He knows the ocean outside Lima as well as anyone. The effects of overfishing have made his memory of the old days even sweeter. Meet him in the award-winning short, 'Home At Dawn.'

ICELAND: Tears of Heaven

Filmmakers L'oeil d'Eos spent last June exploring the secret corners of Iceland. While visiting some of Iceland's more popular sites, they also went off the beaten path to see limitless natural beauty of this country. The trip was described as "26 days of pure wonders from north to south, west fjords to east fjords."

I Tendopoli: The Tent Cities of Italy

Orange season brings thousands of seasonal migrant workers to the Calabrian coast during the winter months. The men live in intimidation from the ‘Ndrangheta, the Calabrian mafia, and were the target of media attention in 2010 when riots broke out between the Italians and the Africans after two migrant workers were shot. This photo series follows Ibra, a man originally from Burkina Faso, who has lived in Italy since 2001 and was living in the tent city for six months when these photographs were taken, working towards his dream of making enough money to return home and provide for his family.

The men living in the tendopoli, which literally translates to “tent city,” pick tomatoes in Naples in the spring and oranges in Calabria during the winter. In the winter months, as many as 2000 migrants live in temporary settlements along the Calabrian coast. That number shrinks to several hundred during the off-season. Some of the men, like Ibra, first traveled to larger cities in the north of Italy and slowly made their way south as job prospects for African migrants became grim. Ibra first set foot on Italian soil in Milan, and has worked in Sicily as well as Naples and Calabria. Occasionally, Ibra takes odd jobs in surrounding towns from Italians he is friendly with. The shantytown where these migrants live lies between Gioia Tauro and Rosarno, two small towns that hug Calabria’s western coast. Residents of Rosarno and the neighboring migrants entered the national Italian spotlight following the killing of two migrants by resident Italians in January 2010. Riots ensued, stirring a national dialogue concerning the treatment of seasonal African workers living in intimidation and squalor. Ibra, a six-month resident of the tendopoli, is often sought out for advice by fellow migrant workers. Fluent in Italian and well-connected in neighboring towns, Ibra helps men living in the camp obtain legal working papers and permessi di soggiorni, “permits to stay” in the country for an allotted period of months to work. He also coordinates the local branch of Caritas, a worldwide Catholic charity aimed at mitigating poverty, serving food to the residents of the tendopoli twice a week. Italy, like all of Europe, is saturated with the same anti-immigrant rhetoric that has fueled the election of far-right leaders across a swath of nations. The future of Ibra, and seasonal migrant workers like him, will be determined by what steps these nations take in restricting their borders, and the official response to informally tolerated discrimination.

Tendopoli. | Located in the deep south of the Calabrese coast about an hour outside Reggio Calabria, this shoddy settlement housing West African migrants was never intended to last long. Hand-erected tents stand next to government-donated ones, housing West African migrants hailing primarily from Mali, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and Ghana. Promises of permanent housing from local Italian governments have proved empty. Meanwhile, the encampment continues to grow in population. This particular tendopoli reached national notoriety in January 2010 following the death of two migrants at the hands of local Italians and subsequent riots.

Emergence. | This tendopoli was slated for destruction following violent attacks on the West African population by local Italians that made international headlines in 2010, in favor of more permanent housing. No progress has been made to construct these permanent homes, and Tendopoli remains active as a settlement.

Accendeva una sigaretta. | Ibra is my guide through the tendopoli. Ibra is originally from Burkina Faso, and unlike most of the men who arrived in Italy from Libya through the perilous Mediterranean sea route, he arrived by plane. He is a polyglot, speaking French, Italian, Igbu, and several bantu languages. Ibra spoke to me only in Italian, and was instrumental in helping with translations during interviews that were conducted partially in French.

La Frutta. | Ibra shares dried fruit from his native Burkina Faso.

Il lavoro del macellaio. | Assan, the butcher, leaves behind a sheep’s head after slicing up a carcass.

Materassi bagnati. | Mattresses dry out following a three-day hail and rain storm.

La tenda d’Ibra. | The blue tents were donated by the government as a temporary measure before permanent housing could be secured. However,the tendopoli encampment has been active for years. What was meant to be a short-time bandaid is currently having to function as a long-term solution.

L’uomo e figlio. | The tendopoli is home almost entirely to men, with only three women and two children recorded as residents. The men follow the seasonal fruit picking terms, Naples for tomatoes in the spring and Calabria for oranges in the summer.

Le scarpe. | Shoes dry on the top of a tent following a three-day rain and hailstorm. Because of its proximity to the ocean, the tendopoli floods consistently in the springtime rainy season.

La salvia d’Ibra. | Ibra keeps fresh sage in his tent for cooking. The electricity in the tendopoli is unreliable at its best; at its worst, it can go out for days or weeks at a time. Cooking on Ibra’s tiny stovetops requires no small measure of creativity and patience.

La bambina. | Leila is the daughter of a woman known to most as Mama Africa. The two live in an apartment in the nearby town of Rosarno, gifting residents of the shantytown supplies when they can afford it. Ibra functions as a liaison between Mama Africa and those living in the tendopoli. He brings Leila gifts when he can.

The Calabrese regional government continues to ignore the conditions of confinement they have created in the tendopoli. With no end of the occupation in sight, the men of the tendopoli are forced to continue living in these atrocious circumstances until administrative compliancy ends.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON FREELY MAGAZINE.

MAGGIE ANDRESEN

Maggie Andresen is a recent graduate of the Temple University Klein College of Media and Communications, where she studied photojournalism and international reporting. She has worked for newspapers in New York, New Orleans, and Denver. Currently, she is a Princeton in Africa fellow working in communications at Gardens for Health International, a small Rwanda-based non-profit working to end childhood malnutrition.

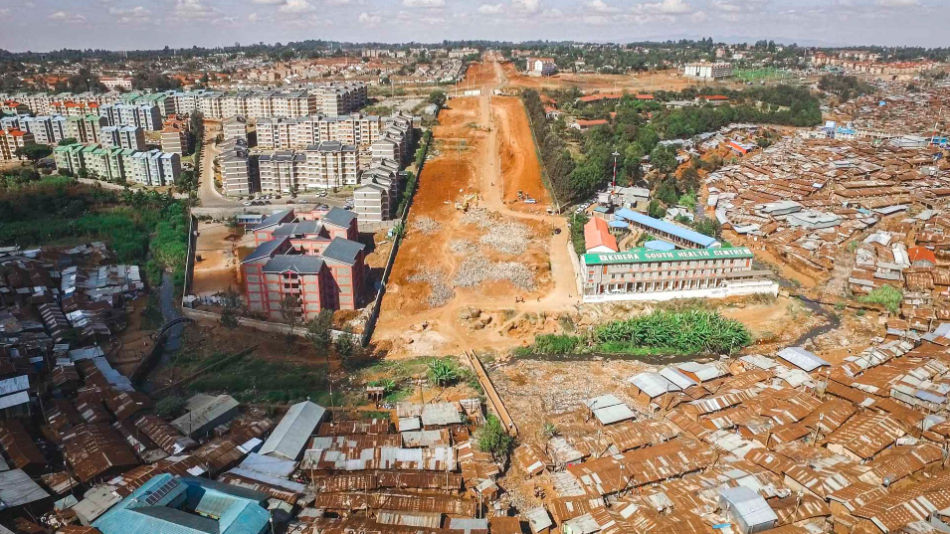

Upwardly mobile Kenyans live in planned, gated communities. Sometimes these abut the poorest of slum communities, this one in Loresho.

Unequal Scenes: Nairobi

“It has been estimated that the richest 10 percent of the population of Nairobi accrues 45.2 percent of income, and the poorest 10 percent only 1.6 percent,” according to a 2009 study on urban poverty by Oxfam.

Statistics on inequality and poverty are ubiquitous in the developing world. They are often underwhelming, however, in their impact. What does 45.2 of income look like? What does “urban poverty” look like? As, of course, every statistic is relative.

The Royal Nairobi Golf Club sits directly adjacent to Kibera slum. Twice a day, a passenger train barrels through the slum, less than a meter away from people's homes and businesses. Next door, people play the game surrounded by greenery.

In Nairobi, a city of chaos, dynamism, and incredible unequal growth, this is even more difficult to portray. Yes, it has easily the poorest urban slums I’ve ever visited. In Kibera, a hilly community, every drainage is choked with tons of raw sewage and rubbish. Children play on live train tracks, running through the middle of the slum. Government services, aside from electricity, are nonexistent. The houses are made from a mixture of mud, sticks, and tin.

But also, yes, the wealthy parts of Nairobi are more difficult to see. They are hidden behind gated communities, ensconced in shopping malls, or wrapped in dingy-looking apartment buildings. Moreover, researching these inequalities is made difficult by the lack of searchable data sets, a draconian drone flying environment, and Nairobi’s infamous traffic problems.

Kibera is constrained not only by infrastructure but also the natural environment. The "river" at the bottom of the slum drains thousands of tons of rubbish into the Nairobi Dam every year.

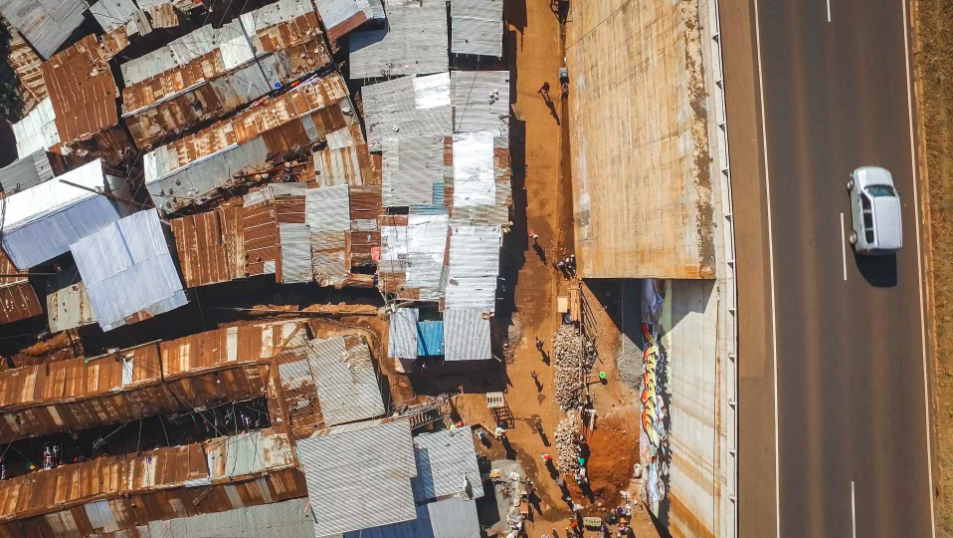

The Unequal Scenes I have found in Nairobi are a mixture of traditional “rich vs. poor” housing images, but also depictions of how infrastructure constrains, divides, and facilitates city growth, almost always at the expense of the poorest classes. During my time there, I focused on a planned road that will bisect Kibera, Nairobi’s largest slum. This road will cut the slum neatly in two, displacing thousands of people, and tens of schools and clinics that are in its way. This road will help alleviate the city’s traffic problem, but it may cause more problems than it will solve. Just to the south, a new road has already cut off part of Kibera, causing people to cross it illegally, resulting in many deaths. From interviews with residents, it is unclear whether or not the planned infrastructure upgrades have adequately taken into account the public opinion.

This dynamism contributes to make Nairobi one of the most fascinating cities I’ve ever been to.

Read more at http://www.thisisplace.org/shorthand/slumscapes/#nairobi-48752

The Southern Bypass road has already lopped a portion off of Kibera, in the quixotic search for a less congested city. Although there is an underpass (visible at the bottom), people often cross the road from above, resulting in many accidents.

A planned road will bisect Kibera slum in Nairobi, displacing thousands of people.

The Southern Bypass road follows the contours of the river and slum next to it. In the distance, you can see the construction beginning on the new road, which will connect Ngong Rd to Langata Rd.

Cars glide over the brand new road, above the slum below.

The suburb of Loresho is home to the wealthy and the poor alike.

As in many places around the world, the rich and poor are separated by only a thin concrete barrier. But it represents much more than that.

These barriers, whether concrete or imaginary, represent an entire class separation, one that may not be surmounted for generations to come.

Amazing geometric patterns emerge from the air. "Straight" lines become slightly curved.

The train is a part of life to Kibera, a source of transportation, of annoyance, of time passing.

The chaos, noise, and density of the slum is neatly juxtaposed with the orderly calm green of the Royal Nairobi Golf Club, which opened in 1906.

THIS ARTICLE AND PHOTO SERIES WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON UNEQUAL SCENES.

JOHNNY MILLER

Johnny Miller is a freelance documentary photographer and filmmaker based in Cape Town, South Africa. His 'Unequal Scences' project is meant to show the stark inequality seen in South Africa and in cities around the world. Check out his website and Facebook to find out more.

Istanbul - Through the Prisma

Filmmaker and digital content creator Justin Heaney makes his first ever live action Prisma video. Applying a Prisma filter to his short film, the spotlight is put on Istanbul, Turkey. The colors and shapes of Istanbul are highlighted through the filter to give off a cartoonish, colorful look while also displaying real life scenery.

VIDEO: Abroad in Cuba

An incredible view of Cuba by filmmaker Akos Papp. Akos describes the short film as a culmination of the "faces, moods, and textures" of Cuba. Different parts of Cuba's distinct culture are represented through street markets, barber shops, street games, factories, and the faces of individuals met along the way.

The Road Story - Vietnam

Georgy Tarasov made a short film starring his own brother, documenting their travel experience through Vietnam. Daniil gets around Vietnam through train, on foot, by bicycle, and by motorbike with many adventures and new friendships along the way.

Moscow Russia Aerial 5K

Come see Russia's capital from the skies in this short film. Produced by Timelab.pro.

I Didn’t Want To Volunteer Abroad, But I’m Glad I Did

Do you know any children between the ages of 3 to 17-year-olds who work 12 hours a day?

Do they skip school because they are working in a market to earn money for their family?

I suppose your answer to the first question is no.

And, maybe your answer to the second is something like “What are you talking about? This doesn’t happen at all.”

Unfortunately, it does happen. Not in your environment, city or town. But it is happening in the world, especially in Quito, Ecuador.

Before my volunteer experience in Quito, I was hesitant to do any sort of volunteer work abroad. Yes, I’ve volunteered in and around my neighborhood. I did so at my mom’s job, at school, at a museum, at a local beach, and at a local community center. But, this was a different experience. Picking up trash at a beach is far from teaching a 3-year-old child basic hygiene or the name of a color.

How do you provide a service to an economic, educational, and social need in another country?

On my first day, I sat in a small, crowded office filled with volunteers who had spent a range of time in Quito. Some had been there for three months, others close to year. The diverse group included volunteers who were single and married. Several were high school students taking a gap year. Also, there were recent college grads. And, of course me. We were from all over the world, such as the US, Australia, England, and more.

At 8 am, we began discussing our plan to spend the entire day in the Ferias, or markets. Some Ecuadorians work in the Ferias working more than 12 hours a day to feed and care for their families. Their employees took care of smaller jobs. Who were they? Their children.

Like every week, the children were going to take an educational break.

I was nervous to begin my volunteer service because I wasn’t ready to interact with the children. I didn’t have the courage to volunteer in the markets. Nor the energy to play with the children. I, too, was anxious that I wouldn’t have the patience to deal with dozens of kids of all age ranges for an entire week.

Silent, I took in the moment and made small talk with the ladies sitting next to me. Though in Quito, we began the morning meeting in English.

We went through the day’s activities, first reciting a song used to help welcome the students to our camp. Some of us were new so we practiced a few more times. The song was meant to energize the children and build rapport with them, the coordinator informed us. It was a familiar song and a chant that the children knew by heart.

We then divided ourselves to lead an age group. I opted for the younger children.

This group was going to learn the color blue. Many did not even know their alphabets. They hadn’t been formally enrolled in school or even had the opportunity to attend.

Sad, yet real for the approximately 600 children we served. Most living on the street spending 12 hours a day bagging items or cleaning their stall.

It stung. Life without going to school? I wasn’t prepared.

We practiced other songs. We reviewed the remaining activities on the agenda. Last, we prepped the canopies, mats, toys, and school supplies to be carried with us to the markets.

Man, what have I gotten myself into.

After collecting a few of the materials, I followed the group to the bus stop. Half took a bus route to one market, while the rest of us ventured off to another.

As I entered the bus and slipped my coins into the slot, I looked for an empty seat near a window. I needed to relax before it was showtime. I peered out the bus window at the locals, the landscape, and the rush of cars dotting in and out of traffic.

45 minutes to our destination, I watched the ebb and flow of passengers crowd the bus. This included men and children hustling onto the bus to make a quick dollar. Between stops, they would repeat their pitch to sell snacks and cheap products. They were hustlers like the children I was about to meet.

We finally arrived at our stop. We collected our items and hustled toward the market.

Outside a small building at the edge of the market, we set up the canopies, positioned the mats in a circle, placed the loads of books and toys on the steps, and corralled the smiling faces toward the washing station. They knew we had arrived when they caught sight of our dark blue t-shirt labeled "Voluntaria" on the back. One-by-one, the children washed their hands in the bowl of soap and water, while suds floated in the air. They gleefully followed suit by cleaning their face.

As they finished, we gathered in a circle. For the newbies, we made our opening song debut. The children sang loudly and proudly. I whispered the lyrics, barely remembering the words from the morning meeting. I tried. Not because I should, but because the children ushered me to do better and be better at living in the moment. So what if I didn’t know the words. Who actually sang (without fear) was a tell-tale sign of who was present and who wore their heart on their sleeves.

Their prowess overshadowed my self-consciousness.

Next on the agenda, we separated into groups. I pranced after the 3 to 5 year olds and partnered with a child named Luis. He was shy and quiet. Me too. Perfect match, eh?

Everyone received a coloring book worksheet and a cap with blue paint. To connect the name of the color blue (“Azul” in Spanish) with the blue paint, they begin finger-painting. There wasn’t much direction needed. He painted within the lines. Most of the children did not. While painting, we repeated the word, Azul. We did so for about 10 minutes.

Antsy and ready for fun, we cleaned up and pulled out books, toys, and sports equipment. Each child grabbed something. Some wanted to play with dolls, others wanted to build with blocks, and a few kicked the soccer ball around. The other age groups included the older children, so it was less play, and more homework. In the middle of playing with one of the smaller children, I assisted a student with her English homework. She was grateful.

The morning went on until it hit noon. We wrapped up the games and fun with our goodbye song. As we sang, the children hugged each volunteer. EACH volunteer! Some twice. I was surprised. They didn’t know me. I didn’t now them. But, they didn’t care. I represented their buddy. I symbolized fun. I was their distraction from work. They were my solace. My humility. The reminder of taking off the blinders of what it meant to volunteer and travel.

The older children left the camp on their own. Volunteers accompanied the younger ones and led them to their parents.

The day was halfway over. We stopped for an hour lunch at a local restaurant.

We returned to recollect our stuff and headed toward our second market of the day. The agenda repeated itself for the afternoon. Exhausted from the course of the morning, I looked forward to meeting the new faces.

The day wasn’t measured in success, but, rather in joy and purpose.

To be clear, this isn’t to boast about “helping” someone else in another country. This isn’t to parade pictures on the internet about a US Citizen helping the “other.” I understand that some people oppose Voluntourism. They're against the lack of stability for the local communities. There is also an ever-changing pool of the volunteers. Look at me, I only volunteered for a week.

Rather, this post is about appreciation for life. Taking lessons even in its smallest dose. Even if the face changes, the blue shirts don't. I keep mine. I keep it for Luis, Pata, Adriana and the other children. I keep it for myself because I selfishly didn’t want to volunteer. But, I’m glad I did.

Day 1 of 7 was complete.

Thank you to UBECI for the opportunity to volunteer with the Street Market Children.

ADRIANA SMITH

Educator, Social Do-Gooder Traveling the World, Footballher. Adriana’s love of Spanish inspired her to study abroad as a first-generation college student. Once she graduated, she became motivated to assist students on their own study abroad and travel journey. While working full-time as Assistant Director of International Programs at Presbyterian College, she blogs at Travepreneur, www.travepreneur.com.

Social Media:

Twitter: @Travepreneur https://twitter.com/Travepreneur

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Travepreneur/

Instagram: @Travepreneur https://www.instagram.com/travepreneur/

Splitting Nicaragua: The People Fighting To Keep Their Country Together

The proposed Nicaragua Canal could be one of the largest engineering projects in history and promises to bring thousands of jobs to the impoverished country. But the government’s secretive deal with a Chinese-led firm has some Nicaraguans raising the alarm about displacement and environmental destruction in the canal’s path.

For LGBTI Employees, Working Overseas Can Be a Lonely, Frustrating and Even Dangerous Experience

As the number of workers taking international assignments increases, companies have more responsibility to look after their LGBTI employees who face persecution while on assignment.

Russia, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia are becoming some of the most challenging expatriate assignment destinations for multinational firms, according to relocation business BGRS. This is in part because some of these countries advocate the death penalty for homosexuality. Other popular assignment destinations include Brazil, India, China, Mexico and Turkey, and these countries exhibit less sensitivity to homosexuality.

International assignments among multinational corporations have increased by 25% since 2000 and the number is expected to reach more than 50% growth through 2020.

The opportunity for LGBTI expatriates and their respective families to be part of an intra-company transfer is statistically likely. Worldwide, the LGBTI population is estimated to be between 1-in-10 and 1-in-20 of the adult population, and over 200 million people worldwide live and work in a country other than their country of origin.

LGBTI employees relocating for a foreign assignment are likely to experience additional hardships compared to the typical expatriate. It’s not uncommon for a destination country to refuse spousal visas if same-sex marriage is not legal in that country.

Likewise, access to healthcare and other benefits can be restricted for those relocating as a same-sex couple. In their study about LGBTI expatriates in dangerous locations, Ruth McPhail and Yvonne McNulty highlighted an interview with one LGBTI expatriate who experienced difficulty in gaining a spousal visa in Indonesia:

I knew my wife would never get a spousal visa in Indonesia; my experience had prepared me for that. So instead I wanted to be guaranteed two things: firstly that my wife could come and stay at least 90 days at a time with multiple entry, and second that if there was a medical evacuation or civil strife situation that we would be evacuated as a family. These two matters were more important to me than what type of visa we were allocated.

On a daily basis, a lack of access to or interaction with other LGBTI families may be common among LGBTI expatriates, and “fitting in” is not always guaranteed. From a career perspective, LGBTI people may face a difficult workplace climate, a perceived lack of career opportunities or status at work.

For example, research shows that lesbians are faced with unique challenges for their career development. These include identifying the right job, and finding a way to get the job and develop on the job. This can easily stifle their potential.

Taking all of this into account, the experience of LGBTI employees on international assignment can be a frustrating and lonely experience. As a result, LGBTI employees may not accept international assignments in the first instance, out of fear of being stigmatised, unsupported or discriminated against by colleagues and the legal system in the host country.

Helping LGBTI employees on assignment overseas

In the end, multinational companies have two choices. One is to turn a blind eye to the challenges faced by LGBTI employees and subsequently suffer the consequences of premature assignment returns and failed assignment costs. The other is taking an equally challenging path by acknowledging the challenges and concentrating on efforts to support LGBTI people through their international assignment experience.

The Williams Institute found that some multinational companies are leading the way by adopting policies specific to LGBTI people. They are reporting improved employee morale and productivity as a result.

If companies are aware that these issues deter LGBTI employees from considering international assignments in the first place, there are effective support mechanisms to use. One option is to map out an LGBTI employee’s career and where that fits with their life goals, because these influence their experience overseas.

Whether or not the employee chooses to disclose their sexual orientation could also affect their assignment overseas. These needs should be weighed up relative to the degree of assignment difficulty.

During an assignment companies can provide additional support to mitigate liabilities, like offering a voluntary reassignment or the option to return home prematurely. As with any good support system, the lines of communication must go both ways.

Multinational corporations have a duty of care to the LGBTI community to ensure that their international assignment experiences maintain a suitable level of support.

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

AUTHORS

MIRIAM MOELLER

Senior Lecturer, International Business, The University of Queensland

JANE MALEY

Senior lecturer in management, Charles Sturt University

RUTH MCPHAIL

Head of the Department of Employment Relations and Human Resources & Professor at Griffith University President RQAS GC, Griffith University

ALBAN ENDLOS – UMDA

To measure up to the electro-acoustic sound and the diversity of Alban Endlos' first album "Goldene Welt / Golden World," filmmaker David Aufdembrinke and his team let their camera travel into another world. During a six week journey from the highest north into the deepest south of India over ten hours of video-footage were generated and combined through an ambitious editing-concept allowing only to use match-cuts. To adapt the analogue nature of the music and the images, the final effects and colortunings were done with a magnet on an old VHS Tape and were composited in an extensive post-production to achieve the effect of a VHS Image in Full-HD Resolution.