A guide to the most beautiful spots to experience in the springtime

Read MoreGuatemala’s ‘Forest Guardians’ Save their Homeland, Providing a Conservation Model for the World

Indigenous guardians in Guatemala's Maya Biosphere Reserve combat deforestation, protecting biodiversity and cultural heritage.

Read MoreThe Ethics of Kelp Farming in Alaska

From food, medicine, climate mitigation and preserving Indigenous traditions, kelp is the shape shifting superhero a polluted world needs.

Kelp with sardines. National Ocean Service. CC By 2.0.

Ethereal and elusive, an unconventional forest grows in the ocean—not full of trees, but of kelp. These captivating, yet occasionally uninviting, greenish tendrils are classified as a type of brown algae that grow as coastal seaweeds; they are typically found in colder waters. In a way, the ethereal kelp borders on the mystical and magical. Kelp is a shapeshifter; a veritable phenomenon that can morph into a variety of forms. Kelp can be used as biofuel, an eco-friendly alternative to fossil fuels derived from renewable biological materials. This multi-talented algae can also be used to make utensils, soap and clothing as well as food—all manner of products people use in their daily lives.

Beyond biofuel, food and everyday household items, the production and usage of kelp is a key debate amongst climate scientists and environmentalists alike. Farming kelp could be a solution in mitigating negative effects of climate change; it could also bolster coastal locations’ economies and positively affect the livelihoods of communities living in and around these shores. But, on the other hand, farming kelp is also fraught with bureaucratic convolutions and, in the long run, could potentially backfire and end up re-polluting oceans. In short, the implications of kelp farming are complex; they are enigmatic and double-edged, much like the kelp itself.

Alaskan Company Barnacle Foods’ Kelp Products. Josephine S. CC By 2.0.

The Eyak People of Alaska—and particularly one Dune Lankard—understand kelp farming. Lankard is the co-founder of The Eyak Preservation Council as well as the President and Founder of Native Conservancy, both of which are groups that support Alaska Native peoples’ efforts in preserving and conserving land and biodiversity on the Alaskan Coastline. People in Alaska and beyond have begun to farm kelp because of commercial, food security and climate change mitigation possibilities. And, because of its optimal climatic conditions, Alaska has become a hotspot for kelp farming.

But why is kelp—this mysterious, gangly sept of seaweed—so valuable and beneficial for the environment? For humans consuming kelp, the benefits lie within its nutritional content: kelp contains calcium, magnesium, iron, vitamin C and potassium. But, perhaps more importantly, people like Dune Lankard and fellow Alaskan kelp farmers are more concerned with kelp’s ability to mitigate climate change. Kelp’s primary ability to mitigate climate change comes from its ability to sequester carbon dioxide. You may have heard of carbon dioxide because it is a greenhouse gas. But, what you might not know, is that carbon dioxide from the atmosphere can also enter the ocean, resulting in a mechanism called ocean acidification.

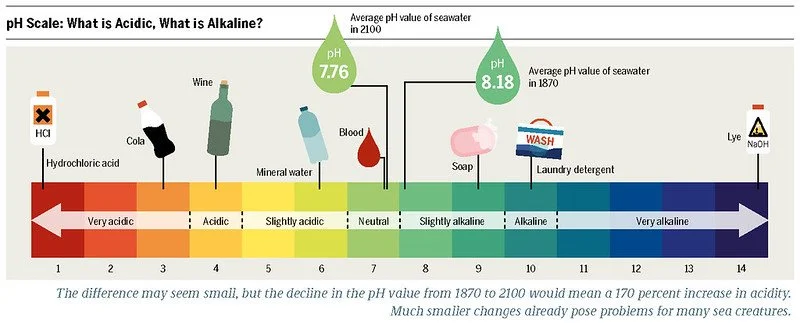

pH reference scale — Ocean Acidification lowers pH. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. CC by 2.0.

As more carbon dioxide enters the ocean and gets absorbed, the pH of the ocean itself decreases, meaning the ocean becomes more acidic. But, this is where Kelp the superhero rushes in and saves the marine phyla. Kelp require carbon to grow because of photosynthesis—they absorb sunlight as well as carbon dioxide to produce the sugar and oxygen they need to live—and, through their uptake of carbon, they leave oceans less acidic and marine organisms more happy. Additionally, when kelp float out to sea and die, sinking deep beneath the surface of the water, their carbon sinks into the depths along with them.

Perhaps it makes sense that kelp, with its bewitching appearance, could be responsible for such intricate—almost magical—climate processes. While there are over 500 species of seaweed in Alaska, the three most-commonly grown species are bull kelp, sugar kelp and ribbon kelp. Bull kelp is strong, almost proud-looking—its thick stalk beholds a sense of authority in the water. Sugar kelp, on the other hand, is more delicately enchanting—its slightly-curled, yellow blades are like rays of sunlight spattering the sea. Ribbon kelp, with its thick spine and greenish appearance, are more reminiscent of a looming forest, or the shifting of willows in the wind.

Bull kelp bulb. James St. John. CC By 2.0.

These kelp, however, represent more than just their life cycle, climate mitigation abilities and appearance. Historically, the Eyak people—located on the Copper River Delta near Cordova, Alaska—have long used kelp for food, medicine and even tools. But, through colonialism and imperialism, some of these traditions were disrupted over decades. Today, however, the Eyak and other Indigenous peoples’ kelp farming has allowed them to reclaim these traditions. Additionally, there are immense economic benefits for any employees involved in kelp farming. The fall-to-spring growth cycle of kelp, as well as the need for regular visitation and observation of kelp farms, offer both seasonal and year-round employment opportunities. The increasing amount of kelp farms subsequently increases the number of job opportunities in Alaska, bolstering the state’s economy. Although mariculture in Alaska is currently a $1.5 million dollar industry, newly awarded $45 million in grants could potentially grow it to more than $1.85 billion in 10 years.

Kelp farming and consumption, however, is not all sunshine and rainbows. One of the most difficult aspects of kelp farming is getting started in the first place—a kelp farm requires a permit. Most states require multi-step permit application through boards of aquaculture as well as departments of fish, wildlife and game. Luckily, on average Alaska has a lower permit processing time than most states. Beyond the bureaucratic complexities of even getting started, there are also questions being raised by environmental and climate scientists about the future of kelp farming. Although—as is outlined above—kelp farming is believed to help ocean acidification through carbon sequestration, some scientists are questioning the ability for kelp to continue to sequester carbon as ocean temperatures warm as a result of climate change.

While people should be mindful of the ambiguous future of kelp farming, for now it is safe to say that the more immediate outcomes of farming are helping kelp maintain a positive reputation. Kelp—delicate and mysteriously distant—is, in actuality, an aid toward a variety of more tangible, positive outcomes. Kelp is food. Kelp is medicine. Kelp can even represent community and prosperity. Of course, kelp can also be a huge factor in sequestering carbon in a post-industrial society. But, for many people, these scientific processes can feel overwhelming or unimportant simply because they seem intangible. This is why the effects of kelp that people can really see and feel—the sense of community, the positive economic impacts and the reclamation of tradition—are something to celebrate. Despite its unconventionality and elusivity, kelp can be a superhero.

Carina Cole

Carina Cole is a Media Studies student with a Correlate in Creative Writing at Vassar College. She is an avid journalist and occasional flash fiction writer. Her passion for writing overlaps with environmentalism, feminism, social justice, and a desire to travel beyond the United States. When she’s not writing, you can find her meticulously curating playlists or picking up a paintbrush.

Guatemala is a Hiking Heaven

With its lush vegetation, cloud forests, and volcanic topography, Guatemala is a hotspot for hikers from around the world.

Read MoreExperience Black Mexico

Black Mexicans celebrate their African heritage through arts and culture.

Read MoreOppenheimer’s Critical Omission: The Relocation of Hispanic and Indigenous Populations

Intricate but incomplete, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer disregards the true history of Hispanic and Indigenous populations in New Mexico.

Trinity Nuclear Test. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. CC0.

A picturesque aquamarine sky hangs lazily above a dusty, deserted New Mexico landscape. Through a tangle of brush, a lanky Robert Oppenheimer, played by Irish actor Cillian Murphy, emerges on horseback. His eyes feast on the remote plains and he declares that besides a local boys’ school and “Indian” burial grounds, Los Alamos will be the perfect site to construct the world’s first atomic weapons.

These momentous decisions and moral quandaries are explored in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. Grossing $450 million in its first fourteen days at the box office, the 1940s period piece has cemented itself as a somewhat unlikely cultural icon. Gone are the days of Nolan’s slightly fantastical films — notably Inception (2010) and Interstellar (2014). Recently, the Academy Award-nominated director has been dipping his toes in the realism of period pieces, beginning with Dunkirk (2017) and continuing with Oppenheimer.

Nolan’s portrayal of Oppenheimer — based on the biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin — is deliberately layered. The audience travels alongside Oppenheimer over the course of his life for three hours. On one hand, Oppenheimer’s humanity is a gut punch: viewers experience his mistress’s death, his tumultuous marriage, and his gradual realization of the death and destruction his scientific creation has wrought. On the other, viewers gaze upon the physicist with disgust: the man was, as he infamously declared himself, a destroyer of worlds.

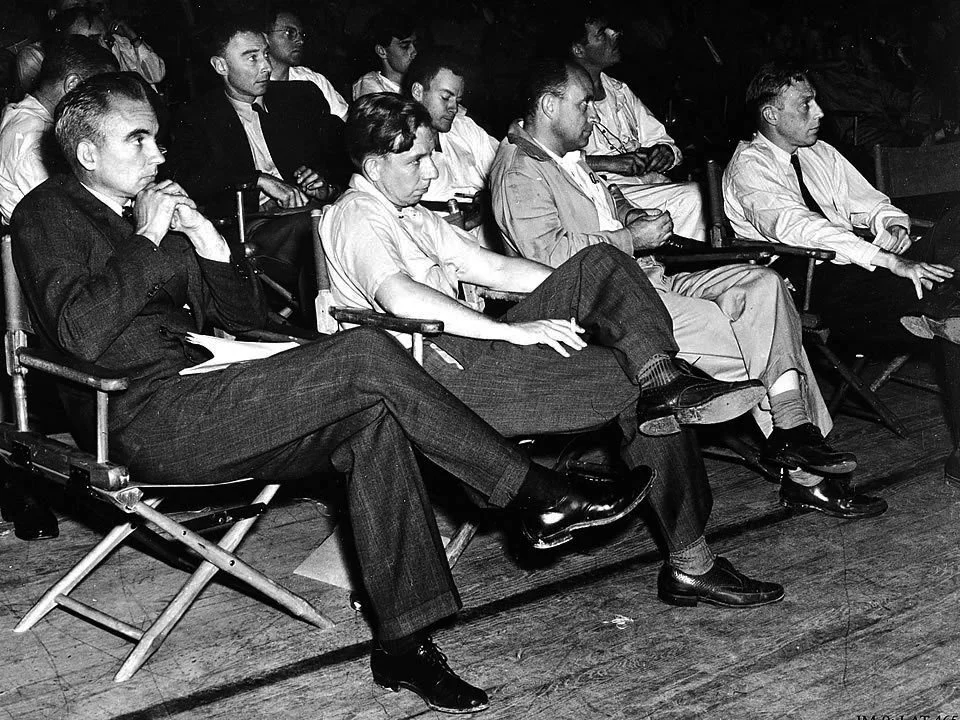

J. Robert Oppenheimer. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. CC0.

The use of the first atomic bomb by the United States to defeat Japan and win World War II is one of the signal events of the modern era, arguably helping to prevent a land invasion of Japan that could have killed millions. Despite the magnitude of this technical and geopolitical accomplishment, the legacy of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will forever cast a negative light on the United States government and the team of nuclear physicists involved in the development of the atomic bomb. While Nolan acknowledges this complex legacy, his portrayal of key elements of the Manhattan Project and the Los Alamos Laboratory obscures another historical moral quandary. The remote sandy vistas in Nolan’s cinematography smother the true story of Los Alamos and the Trinity nuclear test.

The reality, omitted from Nolan’s film, is that during the Manhattan Project the U.S. Government forcibly relocated Indigenous and Hispanic populations that resided in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Contrary to the movie’s dialogue, there were two dozen homesteaders and a ranch occupying the land that was taken by the government for the project, in addition to the school mentioned by Oppenheimer. The government seized the land and offered the owners compensation based on an appraisal of the land — an amount of compensation that the government itself thought was fit. Some homesteaders, however, objected to the compensation offered by the government, considering it far too little. Many in the Federal Government would eventually come to agree with them; in 2004, decades after the original compensation, Congress established a $10 million fund to pay back the homesteaders.

Moreover, it was difficult for the homesteaders to object in the first place due to the language barrier. Most homesteaders spoke Spanish, while government officials often only communicated in English. Some families were even held at gunpoint as they were forced to leave with no explanation, due to the project’s secrecy. Livestock and other animals on property were shot or let loose. Livelihoods were destroyed along with these animals.

Los Alamos Colloquium of Physicists. Los Alamos National Laboratory. CC0.

The element of secrecy surrounding the Manhattan Project and the Trinity nuclear test disrupted the lives of families living directly on Los Alamos land. But, for the 13,000 New Mexicans living within a fifty mile radius of the Trinity test (in Jornada del Muerto, New Mexico), the nuclear explosion truly seemed to be the end of the world. Because the mushroom cloud was visible from up to 200 miles away from the test site, and no civilians knew tests were being conducted, fear erupted in concert with the explosion.

Nolan’s film not only fails to indicate that homesteaders on Los Alamos were forcibly relocated — it also fails to mention that civilians from northern to southern New Mexico were exposed to harmful radiation from the bomb. Radioactive fallout initially contaminated water and livestock, and in turn, civilians. There were no studies or treatment conducted on individuals exposed to radiation, which could have exposed the highly classified program. Those who were in the radius or downwind of the fallout became known as “downwinders,” and began to develop autoimmune diseases, chronic illness and cancer.

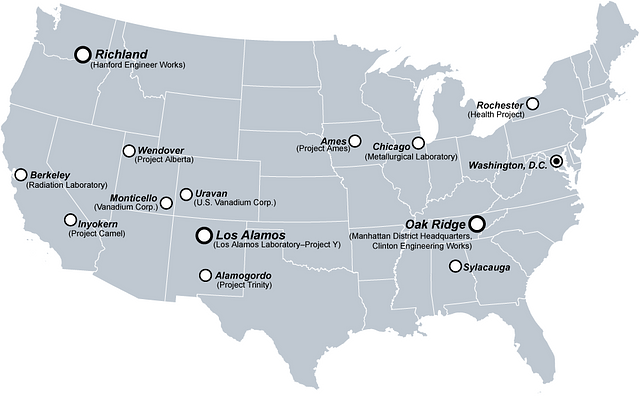

Manhattan Project U.S. Map. Wikimedia Commons. CC by 3.0.

Eventually, the Hispanic American and Indigenous populations who lived in the area returned to Los Alamos to work for the project without knowing its true nature or extent. They returned as maids or as construction workers, often handling radioactive and contaminated materials without knowledge of the harm and risk of exposure. Many became economically dependent on a laboratory that posed environmental and health risks for the greater Los Alamos population. This led to struggles with physical and mental health that have continued to the present time.

The legacy of the Manhattan Project, the Los Alamos Laboratory and the Trinity nuclear test hangs in a state of limbo. It transcends time — becoming the past, present and future for Hispanic and Indigenous populations in New Mexico. Nolan’s failure to acknowledge these populations’ displacement and unwitting contamination silences their narratives and obscures this unique patrimony. J. Robert Oppenheimer’s depiction as a thumbtack in sandy nothingness is historically inaccurate — Nolan’s cinematic depiction of desolation glosses over a more complex reality. Los Alamos was, and is, living and breathing.

Carina Cole

Carina Cole is a Media Studies student with a Correlate in Creative Writing at Vassar College. She is an avid journalist and occasional flash fiction writer. Her passion for writing overlaps with environmentalism, feminism, social justice, and a desire to travel beyond the United States. When she’s not writing, you can find her meticulously curating playlists or picking up a paintbrush.

Frozen Glory: Inside the Eskimo-Indian Olympics

From cultural preservation to sheer athletic spectacle, the World Eskimo-Indian Olympics are a highlight of the Native Alaskan calendar.

An athlete competes in the blanket toss event at the WEIO. KNOM Radio. CC BY-SA 2.0

In the early 1960s, two non-Indigenous pilots who regularly made trips over Alaska’s rural communities kept observing the celebration of an interesting cultural event. This sporting event, as they later came to realize it was, dated back far beyond living memory and honored strength, resilience and endurance through a series of events meant to test the skills necessary to live in such an unforgiving environment. Given that Alaska had just recently become an American state in 1959, the early 60s saw the gradual encroachment of mainstream American culture into its more remote outlying communities, posing a serious threat to local traditions and practices. After the pilots shared their concerns with various groups in Fairbanks, the World Eskimo-Indian Olympics (WEIO) was officially born in 1961 and drew Native participants and spectators from around the Fairbanks area to participate on the banks of the Chena River.

The WEIO has grown significantly since then, with thousands of people traveling to watch the best of Alaska’s Indigenous athletes compete in the Big Dipper Ice Arena for four days each July. Aside from a minimum age limit of 12 years, there are no age categories for any of the events, which means that several generations of the same family can be seen competing against each other. It is also common for older and more experienced competitors to coach and advise the younger athletes during the competition: rather than trying to beat one’s opponents, the larger goal is to compete against and better oneself.

Athletes Sean O’Brien (left) and Chris Kalmakoff (right) compete in the Eskimo stick pull event. Erich Engman. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Many of the events, however, are still extremely competitive, and involve intimate face-offs between athletes. The Indian Stick Pull, for example, calls for athletes to wrench a short greased stick from their opponent, an event meant to replicate the grip strength necessary when trying to keep hold of a freshly caught fish by its tail. The Ear Pull is a contest of stamina to demonstrate the athletes’ ability to withstand pain, a valued trait in the often cruel conditions of the Alaskan North. In this event, string is looped around the opposite ears of two athletes as they face each other as they pull away in a tug-of-war with their ears until one cedes the match.

Other events are competed individually, but with just as much rigor and excitement. The Greased Pole Walk, as its name suggests, tests the balance needed for crossing creeks on slippery logs by having contestants walk as far as they can barefoot along a greased wooden pole. A favorite among both competitors and spectators alike, the Two-Foot High Kick requires competitors to jump vertically and kick a suspended ball with both feet before landing and maintaining their balance. Hundreds of years ago, villages along the coast would perform these kicks as a way to communicate to the village that a whale or some other game had been caught, and to prepare themselves to assist the hunters upon their return.

Athlete Ezra Elissoff competes in the Two-Foot High Kick final at the 2021 WEIO. Jeff Chen. CC BY-SA 2.0

Despite the popularity of basketball and ice hockey, the traditional sports seem to be gaining popularity among young children and teenagers, and are also contributing to the difficult task of preserving and passing on Native Alaskan culture. Miley Kakaruk, a 15-year-old athlete of the Inupiaq tribe of Northwestern Alaska, says that she imagines her ancestors competing in the same events centuries ago, vying to be chosen for their village’s next hunting party. Because each event is so heavily rooted in their history, younger competitors are able to learn the customs and stories that so heavily influence the culture and lifestyle of their people.

Equally important is the power of these games to forge a connection between athletes and society. Historically, studies have shown that Native Alaskans suffer from some of the highest rates of alcoholism and drug abuse in the US. A number of the people that the WEIO Board works with and recruits are young adults who are at risk of or actively battling addiction. According to Gina Kalloch, a board member and ex-athlete, discovering their culture through such a fondly practiced social tradition has allowed many of these people to develop a sense of pride in themselves and their culture, and helped to reorient their lives.

Native Alaskan women compete in the Miss WEIO Cultural Pageant alongside the athletic events each year. Danny Martin. CC BY-SA 2.0

While this year’s edition of the Olympics already took place between July 12 and 15, highlights of both the sporting events and the accompanying Miss WEIO Cultural Pageant are freely available on the internet.

Tanaya Vohra

Tanaya is an undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health at the University of Chicago. She's lived in Asia, Europe and North America and wants to share her love of travel and exploring new cultures through her writing.

Why You Should Visit the Makah Tribe on the Coast of Washington State

Visiting this region offers a unique opportunity to immerse yourself in a rich Indigenous culture that dates back thousands of years.

View from Cape Flattery Bluff. Manuel Bahamondez H. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The Makah Tribe's reservation, resting on the extreme northwest tip of Washington State, boasts an ethereal landscape and thriving cultural practices. The land and the Tribe's community inspire and nurture ongoing engagement with nature and rich family connections. Despite its remote location, accessible by a single, winding route, the rich culture and natural beauty of this community offer a magical experience for curious travelers.

The reservation sits at the farthest point north and west in the continental United States, cradled between gentle hills covered by tall Douglas Fir, Sitka Spruce, and Western Red Cedar trees on one side and the rugged Pacific coastline on the other. In the wake of a century-long fight against colonization the Makah continue to protect their sovereignty through the teaching of their Indigenous language, the celebration of cultural rituals and artifacts in their local museum and schools, and the preservation of the tribe’s traditional and sustainable reliance on native plants and animal species. The Tribe welcomes visitors from near and far to reflect on the reservations’ deep culture and lush natural landscapes. Hiking, surfing, and other outdoor activities are easily accessible from this scenic location and cultural hub. Visiting the Makah Tribe offers a unique opportunity to immerse yourself in a rich Native American culture that dates back thousands of years. The stunning natural beauty surrounding the Makah Tribe, including picturesque beaches and rugged cliffs, provides a breathtaking backdrop for your visit.

Sunset on First Beach. Jaisril. CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

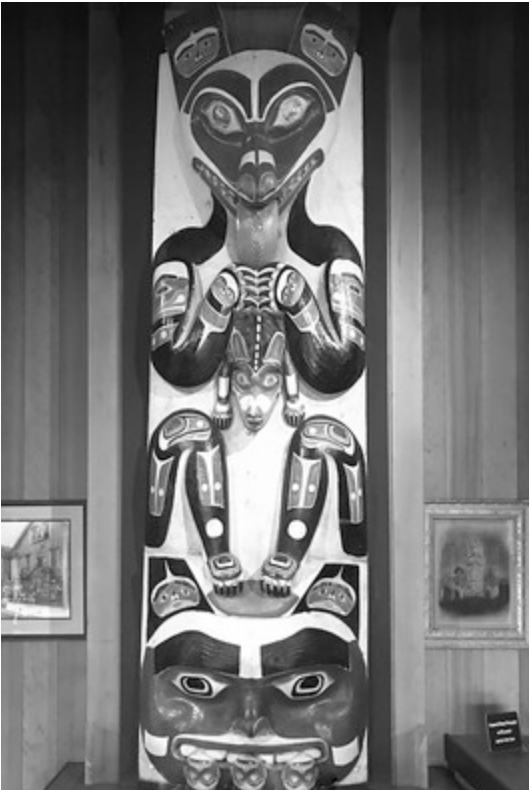

Generation after generation, the fabric of the Tribe’s community is woven through its cultivation of the natural world and artistic endeavors. Today, a significant number of Makah individuals thrive as artists, making a living through the sale of intricately crafted goods which are sold to galleries, shops, and collectors across the globe. A major source of income comes from the exportation of these artistic goods and is a key element of the Tribe’s livelihood. Carvings and masks in particular are a distinct feature of Makah art and have garnered the attention of tourists and art sellers alike for generations. The pieces often feature animals that hold deep cultural importance to the Makah. Whales, salmon, halibut, ravens, eagles, otters, herons, and wolves are commonly depicted in these designs. Each carving tells a story, chronicling the rich narratives of the origins and struggles which are passed down through generations within the community and amongst families.

The Makah are highly skilled woodworkers, capable of fashioning a wide array of items from the trees that thrive in their surrounding forests. While western red cedar is most frequently used, you can also find artists working with alder, yew, and spruce. Carvings range in size, from intricate jewelry to grand ocean-worthy canoes and towering totems. The incorporation of nature imagery and the sourcing of natural materials reinforces and honors the Makah’s reverence for their lands and waters.

Example of Makah style art. A. Davey. CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

Long before the advent of written language, the tribe used dance, song, and storytelling to receive and retain intergenerational knowledge. These melodic traditions are shared and reinforced on various occasions, including weddings, naming ceremonies, memorials, and other family or community celebrations. The Makah reservation museum hosts a compelling collection of artifacts, information guides, as well as a garden with plants labeled with the native language and traditional uses.

For instance, the tribe once maintained five, thriving and permanent villages: Waatch, Sooes, Deah, Ozette and Bahaada. Their ancient way of life began to shift in the late 1770s, when Spanish explorers first settled in and around Neah Bay in 1779. The Spanish and other European groups were eager to exploit the natural resources of the Makah's land and brought in non-Indigenous modes of technology, among the most important of which were guns. The exploitation of the land's natural resources resulted in extinction of native plants and animals (e.g., otters and whales). Not only did the Europeans bring new technologies, they brought diseases, such as smallpox and measles, which plagued the less resistant indigenous communities. The Tribe's traditional ways of life were disrupted, and its inter-generational familial and domestic structures were gravely impacted as a result of death and the loss of land ownership. In the winter of 1855, Makah leaders and the American government signed theTreaty of Neah Bay, which stipulated that the Tribe give up ownership of much of its land, with the exception of rights for certain Indigenous practices, such as whaling, seal hunting, and fishing. The Makah were forced to cope with changes and shift to a more European lifestyle. In exchange, the United States government promised to provide public education and health care. To this day much of the tribe’s coastlines and forests are still under shared jurisdiction with the National Parks Service and the United States Government.

Makah Whale Hunting Ceremony. U.S. Forest Service- Pacific Northwest Region. CC0

As with so many Indigenous tribes across the country, the Makah have resisted the pull of corporate behemoths endeavoring to exploit the natural resources and cultural traditions that rightfully belong to the tribes. These tribes have fought to ensure their histories are not just archived but are alive and flourishing. One of the best ways to protect the ongoing strength of these communities is to visit these places and engage respectfully with the work and lifestyles of the Indigenous peoples, and to listen to and learn their histories.

Avery Patterson

A rising junior at Vassar College in New York State, Avery is a Media Studies and French double major. She is an avid reader, writer, and traveler. She loves to immerse herself in new cultures and is an avid explorer who loves being in nature. She is passionate about climate and social justice and hopes to use her love of writing as a catalyst for positive change.

How Malaria Might Make a Comeback in the US

In order to prevent another pandemic so soon after the last one, US authorities need to stop this new malaria outbreak in its tracks.

The female Anopheles mosquito plays host to the disease’s parasite. CC BY-SA 2.0

Over the past two months, seven cases of locally acquired malaria have been identified in the US. These cases, six of which appeared in Florida and one in Texas, have drawn significant attention as the first time in 20 years the disease has been transmitted domestically. At present, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported that all five patients have received medical treatment and are recovering positively, and that the risk of malaria reappearing in a more widespread epidemic across the U.S. is extremely low. That being said, this is a good reminder for those in charge of American public health infrastructure to reflect on how best to shore up national defenses, especially in the wake of the recent Covid-19 pandemic.

Malaria is caused by parasites, which commonly infect Anopheles mosquitoes, and who in turn transfer the disease to humans when they inject their proboscises into our bloodstreams. There are several species of the malaria parasite, collectively known as Plasmodium, some of which cause more serious cases than others, but all of which require tropical climates to thrive. Regardless of the species, malaria is still extremely serious and symptoms such as high fevers, chills, and nausea begin to manifest in a few weeks. Most worryingly is that malaria, if left untreated, is fatal. As of 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) believed that a grand total of 247 million cases of malaria occurred around the world, of which 619,000 were fatal. The majority of these deaths were children in various countries in Africa, where malaria is a constant present threat and contributes to a vicious cycle of social and economic poverty, taking a massive toll on countries in already precarious situations.

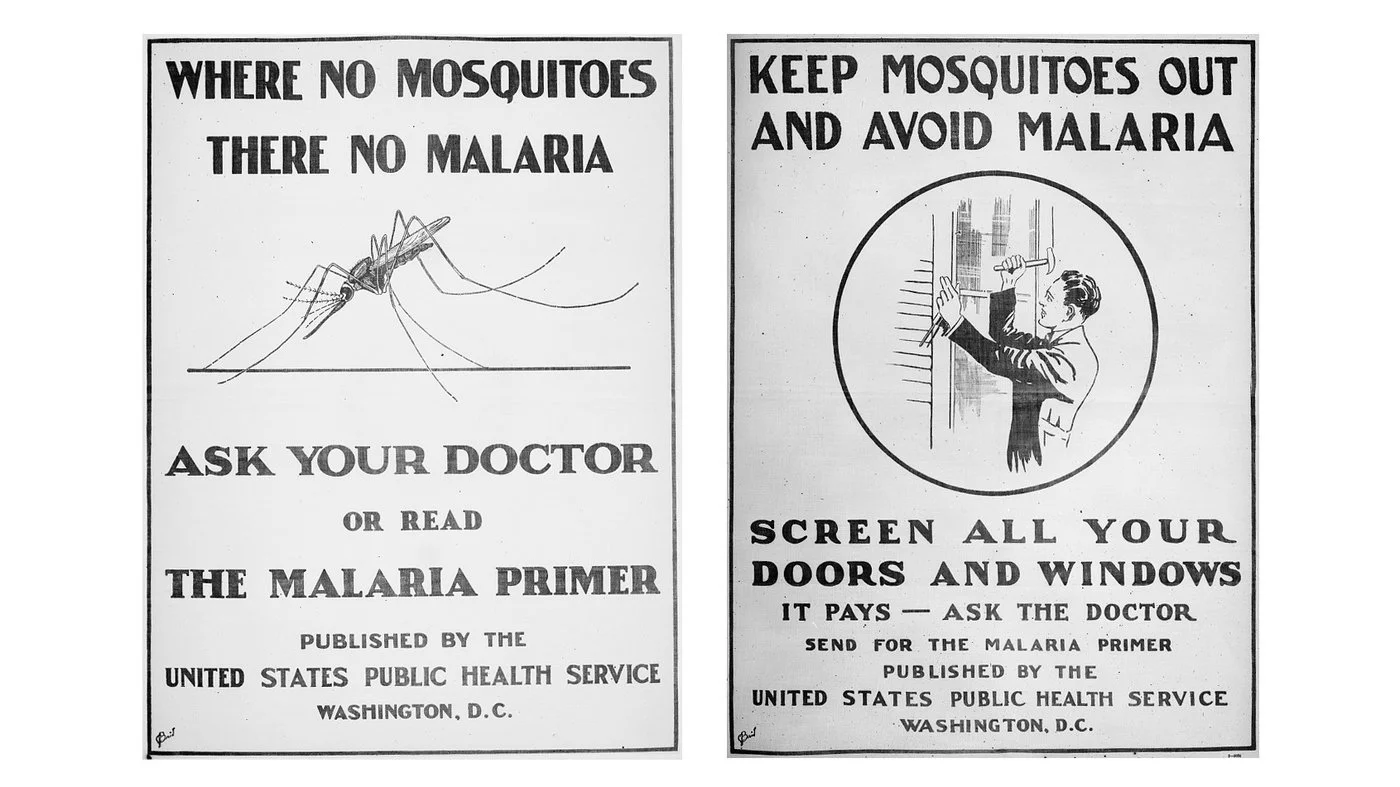

Malaria awareness in the US during the 1950s. Library of Congress. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

At the beginning of the 20th century, malaria was considered an extremely serious issue in the US; the CDC was actually founded in 1946 to eliminate the disease. Over the next six years, various public health measures such as insecticide use and window screens were implemented to reduce the 15,000 cases reported in 1947, and in 1951, the CDC finally announced that malaria was in the US no longer. This remained the case for decades, until an incident in 2003 when eight locally acquired cases in Palm Beach, Florida were identified. Fortunately, the outbreak was quickly quashed thanks to an immediate response campaign that completely rid the area of mosquitoes to prevent transmission. Since then, malaria has remained fairly absent from the American healthcare landscape.

It is important to note, however, that malaria has never been completely extinct in the US; prior to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, roughly 2,000 cases of the disease were identified and reported annually in patients who had traveled to countries with high incidences of malaria in Southeast Asia and Africa. Additionally, once infected individuals return to the US, local mosquitos who feed on them can pick up the parasite and spread it further. Every so often, this may result in a small reintroduction of the disease and potentially even some limited transmission, but there has never been any worry of it resulting in a much widespread epidemic.

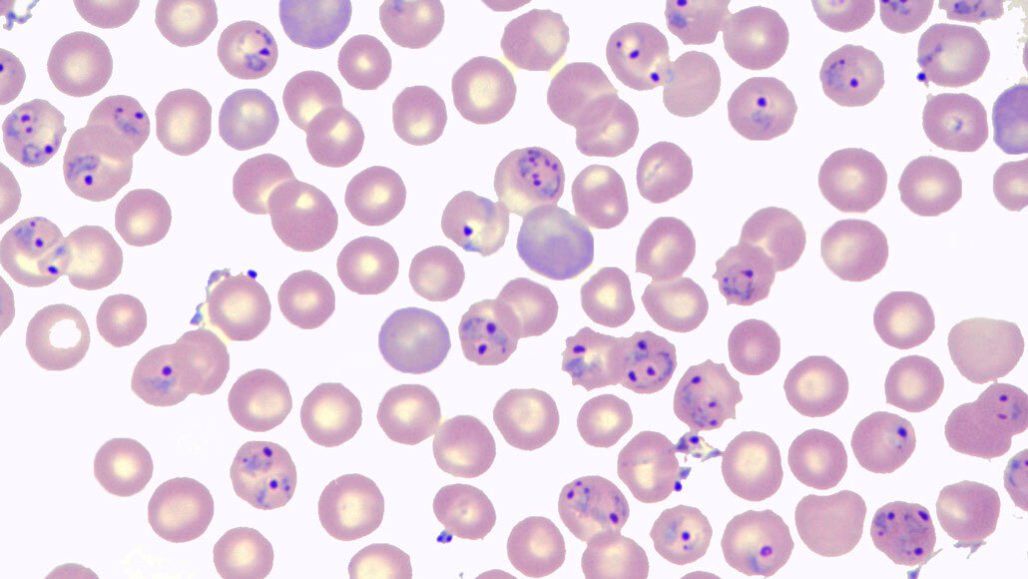

The malaria parasite pictured under a microscope. Joseph Takahashi Lab. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The reason these recent cases received so much attention were that all five were acquired locally within the US, which likely indicates that the parasitic mosquito population has made a resurgence as well. Thankfully, the species of parasite identified to have caused this small outbreak is known to transmit one of the milder forms of the disease, but that in no way detracts from the gravity of the situation. Matters of public health have become much more salient in regular discourse since the COVID-19 pandemic, and with it, some extreme opinions about containing and treating transmissible diseases. While America’s healthcare infrastructure continues to operate in largely the same way as it did during the 2003 outbreak, experts have agreed that public cooperation is now more important than ever if this re-appearance is to be nipped in the bud.

The RTS,S malaria vaccine. TheScientist. CC BY-SA 2.0

One particular area in which this agreement would go a long way, is that surrounding the efficacy of vaccines. In October of 2021, the WHO officially recommended the use of the RTS,S malaria vaccine developed by GlaxoSmithKline to prevent transmission in regions with high incidences of the disease. In addition to being logistically simple to store and administer, trials proved that the vaccine was beneficial to 90% of those treated, a staggering figure in the world of pharmaceutical development. Introducing the vaccine to the U.S. seems like an obvious step to take in the wake of these recent malaria cases, especially given the low price of a single dose at $9.30.

Vaccines have been a hotspot of controversy over the past few years, with many people denouncing both their safety and efficacy as a preventative treatment. Government authorities and healthcare professionals and academics around the world continue to release studies and evidence to show that vaccines are essential to build up individual and population-wide resistance to a variety of diseases, but large groups of the public still remain unconvinced. Among the many lessons and important takeaways from the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of vaccinations is among the most important, especially in the face of a potential re-emergence of a disease as deadly as malaria.

Tanaya Vohra

Tanaya is an undergraduate student pursuing a major in Public Health at the University of Chicago. She's lived in Asia, Europe and North America and wants to share her love of travel and exploring new cultures through her writing.

A Sustainable Guide to the U.S. Virgin Islands

The U.S. Virgin Islands offer a gateway into a world of rich marine life, lush vegetation, and a complicated global history.

Read MoreAn Ethiopian’s Path to From Refugee Camp to College Campus

How a refugee survived genocide and rebuilt a life in the United States.

Omot retelling his journey coming to the U.S. during our interview. Image courtesy of Ojullu Omit.

This semester, I had the privilege of connecting with Ojullu Omot, whose life was forever altered by tragedy. On December 13, 2003, when he was just 14 years old, Omot experienced a massacre at his hometown in south-west Ethiopia. As part of a Wake Forest University project to raise awareness about the challenges faced by refugees, a team made up of me and my classmates produced a 10-minute advocacy film that aims to shed light on the often-overlooked struggles refugees encounter while adapting to life in the United States. Omot’s story is a testament to the blend of heartbreak and perseverance that characterizes the ongoing global refugee crisis, capturing the resilience and fortitude of those seeking haven away from home.

Omot’s story began with displacement, as he fled the 2003 massacre in the remote Gambella region of southwestern Ethiopia. From December 13-15, in a reprisal against a small ambush against Ethiopian federal government officials, ethnically Amhara, Oromo, and Tigrayan soldiers and rioters murdered hundreds of minority Anuak civilians. Human Rights Watch’s report suggests that these atrocities should be considered crimes against humanity. . The Ethiopian government claimed that only 57 were killed and that the violence resulted from ethnic tensions between rival Anuak and Nuer groups, in contrast to the claims of international human rights groups and the Anuak themselves. Human rights NGOs have called for a thorough investigation into the incident, with concerns that others like it could occur. Despite facing deadly tragedy along with the immense challenges of settling into a new society as a refugee, Omot has found a new home in the United States, where he serves as a living witness to the egregious human rights abuses of his homeland. He remains committed to starting a new chapter in life.

By now Omot has gotten used to retelling the story of how he left his home in Ethiopia in the midst of genocidal violence, and his journey from there to become an international politics student in the United States. The three-day-long massacre in Gambella town of southwestern Ethiopia was an outburst of ethnic conflict between the indigenous Anuak group and members of the Ethiopian military. As the situation in Ethiopia deteriorated, Omot moved to Sudan when he was a teenager, with the hope that things would get better in a year or two.

But they didn’t. The military confrontation neither started, nor ended with the massacre. More than 10,000 Anuak people were forced to leave Ethiopia in 2004, the year after the massacre took place.

Omot left Sudan for Kenya after two years of waiting. The unrest had separated him from his family, and he lacked many colorful memories about his childhood in Ethiopia, Sudan and Kenya. What he remembered is playing football with his friends in refugee camps everyday; many of those eventually being sent to Canada, Australia and other developed nations. Omot remembers planes from the United Nation hovered above their heads in refugee camps, dropping food and supplies and people hurrying to grab them. “We were dependent on the refugee program,” Omot said, “Resettlement in the United States was not a typical solution for refugees living in the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees(UNHCR) camp.”

Omot never dreamed about coming to the United States then. He was invested in the idea that everything will go back to normal in Ethiopia, and that he could then return home. Yet Omot’s life took a major turn in the year 2016. He was called for an interview, which he later found out was part of the application process by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services employees concerning whether he is eligible for resettlement in the United States as a refugee. The approval rate for a refugee status in the United States is 27%, according to World Data.

Omot waited for roughly six months until he was called for a series of security checks, examinations and orientation. In February 2016, International Organization for Migration contacted Omot, telling him that his case is ready. He then boarded a plane to the United States on April 4th, 2016, his first ever flight. When he landed in Miami, Florida, it was like landing on a new planet- the shock of the novel language and lifestyle almost dazzled the then 28 year old.

“There was something change, [such as] the day became longer, I was not even comfortable, and I cannot see where I come from, ” Omot recalled his initial exposure to the United States, “The first question I asked myself [was], is this the U.S. [as] I expected it?”

And the first few months continued to affirm to him that starting anew wasn’t easy. Omot often found himself alone in his house assigned by the government, since his roommates busied themselves working in the daytime, and went straight to sleep not long after walking in the door at night. Comparing the situation to the community life in Ethiopia, where everyone would sit down and share stories after a day’s work, filled Omot with homesickness at night.

Language is also a major challenge to Omot. Going to a university was at the top of his wish list when he came to the United States, but he couldn’t even understand people’s accents when he asked for directions on his way to school. He had no idea how to open emails during his first semester at a community college. When one of his classmates finally taught him how to view the inbox, he found emails from professors flooded in there. In winter, the temperature dropped so low that Omot, who used to live near the equator, had to drop his English as Second language (ESL) classes to avoid traveling in freezing weather.

But Omot is determined to realize his dream. Instead of “wasting time” in ESL classes, he decided to push himself, taking the General Educational Development (GED) tests directly. He works as a hospital janitor in the daytime for living; in the evening and before dawn, he dives into his study. Whenever he had free time, Omot would peruse his textbooks, went up to the library of the community college he attended everyday, asking every librarian what GED looks like, and tips and tricks to score higher.

The global refugee population has reached crisis proportions, with more than 30 million refugees displaced in 2022, signaling a significant surge from the previous year's level. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has reported a staggering total of 103 million people forcibly displaced as of mid-2022. In response, President Joe Biden has committed to revamping America’s current “inhumane” immigration policy. However, the administration's effort to admit refugees has fallen significantly short of its goal, with only 25,465 individuals granted admission by the end of the previous fiscal year on September 30, 2022, a mere 20% of the objective. The number of refugees received by the United States still remains one of the lowest among all nations, and the number continues to decrease.

Refugees face a plethora of challenges when they resettle in a foreign country, with attaining secure housing among the most pressing. Asylum seekers in particular struggle to obtain temporary housing due to a lack of government support and unfamiliarity with the US housing system. Non-profit organizations and shelters provide vital assistance to these individuals. Despite this aid, refugee and asylum seekers are disproportionately at risk for health problems, both physical and mental. They are more susceptible to severe mental health conditions like PTSD and depression, while chronic illnesses like diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease exacerbate their already challenging circumstances.

In 2017, Omot took the GED for the first time. And hard work pays off — he passed the test.

“It [passing the test] gives me hope that I could continue to do all of them,” said Omot, breaking into a smile. And he did. After he finished with GED, Omot is currently pursuing a bachelor degree in international politics at University of North Carolina Greensboro. When asked why he could recall his story in astonishingly clear detail, Omot answered, “I think my story is important because if other people, other refugees heard about it, they would think, oh, this guy did that and starting his new life. Maybe I could do the same.”

To Get Involved:

While Omot is navigating through his new life in the United States, it is not without support from various refugee organizations, such as Every Campus a Refugee (ECAR), an organization aiming to mobilize colleges and universities to host refugees on campus grounds and support them in their resettlement. ECAR provided nearly 4 years free housing and accessories to Omot, and provides several other services to refugees in the North Carolina region. Learn more about ECAR here.

Hope Zhu

Hope is a Chinese international student at Wake Forest University in North Carolina studying sociology, statistics, and journalism. She dreams of traveling around the globe as a freelance reporter while touching on a wide range of social issues from education inequality to cultural diversity. Passionate about environmental issues and learning about other cultures, she is eager to explore the globe. In her free time, she enjoys cooking Asian cuisine, reading, and theater.

Eat for Under $15 at these 7 Global Cuisine Restaurants in NYC

Let your tastebuds travel without leaving the Big Apple.

Chinatown in New York City. Norbert Nagel. CC by 3.0.

Beyond its famous museums and fashion, New York City is recognized as the food capital of the United States. Every year foodies flock to the city’s restaurants for unique menus and interpretations of global cuisine. But this top-notch culinary environment typically comes—quite literally— with a price. New York restaurants are often criticized for their exorbitant prices. But fear not, there are plenty of restaurants in the city that offer authentic international cuisine for a reasonable price. Whether you are a college student on a budget or a lifelong fan of global cuisine looking for food made with a lot of love, these restaurants will leave both your stomach and your wallet happy.

1. Super Taste

Hand-Pulled Noodles with Lamb. Jason Lam. CC by 2.0.

Located in the famous culinary neighborhood of Chinatown, Super Taste may be the most well-known restaurant on this list. If you find yourself craving Chinese food, Super Taste is a classic, must-go stop. The most notable dish on the menu is their hand-pulled noodles. These silky and addictive noodles can be paired with chicken, beef, or mutton at the customer’s request. But if you aren’t in the mood for noodles, the five for $10 pork and chive dumplings drenched in sweet-spicy chili oil are always a crowd pleaser. Although there is limited seating inside, Super Taste is perfect for on-the-go enjoying. Their menu can be found here.

2. Pyza

Borscht topped with sour cream. Liz West. CC by 2.0.

Warm and delicious, Pyza serves Polish food so good it could be mistaken for a home-cooked meal. Located in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, this restaurant specializes in plates piled high with food that makes you feel like family. Its menu features traditional dishes like stuffed cabbage, tongue in horseradish sauce, and various types of pierogies. A stand-out dish is their chicken cutlet, breaded and paired with a dollop of sour cream. Their soups range from a reasonable $5-$8, so tuck in with a bowl of borscht and enjoy the homey atmosphere. Additional items and prices can be found here.

3. Birria-Landia

Brooklyn location of Birria-Landia. Andre Carrotflower. CC by 4.0.

This Mexican spot may differ from most foodies’ perceptions of a typical restaurant. Instead of a usual sit-down experience, Birria-Landia started as a single Jackson Heights food truck. The operation has since expanded to include additional trucks in the Lower East Side, the Bronx, Jackson Heights, and Williamsburg. Their specialty dish, birria, features tacos topped with fresh cilantro and salsa paired with a rich, smooth dipping broth. The meat of the tacos—often beef—is first marinated in mixtures of spices and dried chillies before being cooked low and slow in broth. This lengthy process creates mouth-watering and juicy tacos that can be enjoyed for only $4.50. In addition to their exceptional tacos, their consummé broths, tostadas, and quesadillas can be found here.

4. Kassim’s Bakery

Aalu Roti. Guarav Dhwaj Khadka. CC by 4.0.

Whether you prefer your dishes savory or sweet, there is something for everyone at this Queens restaurant. Kassim’s serves a wide variety of Caribbean lunch and dinner foods, but also offers a tasty variety of pastries and baked goods. One of the menu’s highlights is the selection of roti; each variation of the dish is under $10. Roti is a wheat flatbread that at Kassim’s is paired with beef, chicken, duck, goat, and pachownie (innards of lamb). After finishing a main dish, customers can explore Kassim’s dessert menu. Their cassava pone is perfect for those with a sweet tooth; cassava, also called yuca, has an edible root often used to make starchy desserts. More of Kassim’s sweet and savory treats can be found here.

5. Punjabi Grocery & Deli

Samosas paired with chutney. K Spoddar. CC by 4.0.

Can you claim to have visited New York if you didn’t find yourself in a deli at some point during the trip? Although it also doubles as a grocery store, this Lower East Side joint’s Indian food makes it stand out. Even better, the deli only serves vegetarian food, making it the perfect spot for travelers with this dietary restriction. At only 50 cents, Punjabi Deli might have the most affordable Samosas in the city. They also offer an assortment of rice dishes where customers can mix and match different vegetable options to create the perfect bowl for only $6 or $8, depending on if you want a small or large meal. The $2 chai is a perfect way to wash everything down. More exciting dishes and beverages can be found here.

6. SVL Souvlaki Bar

Grilled kebabs. Glen Edelson. CC by 2.0.

From spanakopita to greek fries, SVL Souvlaki Bar combines tradition with innovation to create unique Greek food. They have two Queens locations, with one on Steinway Street and the other on Astoria Boulevard. Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this quick and fresh spot is their “build your own” options. You can customize salads and bowls, or even create entire plates filled with pita, kebabs, vegetables, and sauces. Their iconic SVL sauce combines sweet, tangy, and creamy flavors— it is the perfect way to top off any customized dish. Or, if the extent of customization is intimidating, you can always enjoy classic chicken souvlaki kebab for only $4.50. Even better, the Bar’s food is made with hormone-free meat and fresh produce. Read more about their ingredients, mission, and menu here.

7. Bunna Cafe

Injera topped with assorted vegetables. Kurt Kaiser. CC by 2.0.

If you’re looking for more of a sit-down experience, Bunna Cafe is the perfect destination. They are a Black-owned and vegan Ethiopian restaurant located in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The restaurant’s family-style meal environment creates the perfect atmosphere for hearty food paired with good conversation. Scoops of vegetables are served in piles on injera, a fermented sourdough flatbread. Customers can select a variety of different sides, mixing to create new flavors and combinations. Or, if you’re dining alone, the $12 lunch special comes with individual scoops of four different items. Although, with such generous portions, you may want to bring a friend to share. Further details about their menu and strong variety of sides can be found here.

Carina Cole

Carina Cole is a Media Studies student with a Correlate in Creative Writing at Vassar College. She is an avid journalist and occasional flash fiction writer. Her passion for writing overlaps with environmentalism, feminism, social justice, and a desire to travel beyond the United States. When she’s not writing, you can find her meticulously curating playlists or picking up a paintbrush.

Travel to NYC, Not for Times Square, but for the Parks

Check out the many green areas in NYC where culture and nature abound.

Read MoreVIDEO: Mexico’s 600-Year-Old Dance of the Flying Men

For the past 600 years, dancers in Papantla, Mexico, have taken to the skies to perform the acrobatic spectacle, the Danza de los Voladores (Dance of the Flyers). Four flyers and one guide dressed in vibrant colors ascend a 20-meter pole, anchored only by a single rope tied to their legs. There, they begin the ritual, flying through the air to ask the sun deity for rain and blessings.

Read MoreBeyond the Binary: Mexico’s Muxes Break Traditional Gender Norms

Travel to the Mexican state of Oaxaca and you’ll find muxes, third-gender identifying individuals whose very existence breaks the gender binary. While muxes today face barriers to equality, their rich culture represents the best of the indigenous Ismto Zapotec culture.

Read More8 Immigrant Neighborhoods in the United States That Offer Glimpses of Another Country

Explore world cultures without leaving the United States in these 8 diaspora neighborhoods.

Read More7 Sites of Mexico City’s Architectural Diversity, from Baroque to Brutalist

Mexico City is a flourishing metropolis with a plethora of historic and modernist architectural sites. Here are a few attractions scattered around the city.

Read MoreThe Decriminalization of Illicit Drugs in British Columbia

Canada has announced their plans to decriminalize small amounts of illicit drugs in British Columbia by January of 2023. They are hopeful this will lower high rates of overdoses.

Graffiti about drug decriminalization. Ted’s Photos. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

In British Columbia, Canada, where thousands of overdose deaths occur each year, officials have decided to try decriminalizing small amounts of illicit drugs. The illicit drugs in question include heroin, cocaine, opioids, methamphetamine and more. Residents of British Columbia 18 years or older will be allowed to possess a maximum of 2.5 grams of these drugs without penalty, a policy that will take effect in January of 2023. This policy comes from an exemption from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act that makes these drugs illicit, which was granted to British Columbia for a three-year trial run.

Officials hope that by decriminalizing small amounts of these drugs, dependent users will feel less afraid of prosecution and stigmatization if they do decide to seek drug-related help. Further, by tackling rates of drug deaths as a public health issue, BC Government News says “the Province will create new pathways to support those seeking treatment.”

Since the height of the pandemic in 2020, British Columbia has struggled with high rates of illicit drug abuse and overdose deaths. In 2020, drug-related death rates rose into the two-thousands, a problem that since 2016 had been declared a public health crisis. Most of these deaths occur when drug users hide their addiction from friends and family, fearing the reaction or stigmatization that will come from their loved ones learning of their addiction.

By decriminalizing these drugs, Canada hopes to reverse this effect; Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer, wrote in a tweet: “Stigma and fear of criminalization cause some people to hide their drug use, use alone, or use in ways that increase the risk of harm. This is why the Government of Canada treats substance use as a health issue, not a criminal one.”

Street use in Vancouver. Ted’s Photos. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The exemption to be instituted in 2023 has found support from family and friends of deceased drug users and was even supported by the police associations and chief coroner. Though some call for even further decriminalization – a policy that would expand the 2.5 gram limit to larger amounts – health officials in Canada believe 2.5 grams is a good trial starting point. Harm reduction is their main goal; British Columbia’s Provincial Health Official Dr. Bonnie Henry stated, “This is not one single thing that will reverse this crisis but it will make a difference.”

In requesting an exemption from the Controlled Drug and Substances Act, British Columbia also stated that drug-related felonies and arrests disproportionately affect already marginalized communities. In decriminalizing small amounts of drugs, the authorities will reduce punitive actions and may help to decrease the stigmas around drug use that cause people to hide their addictions.

Turning Point of Tampa has also stated that experts on drug incarceration have stated that imprisonment does not deter drug use, and problems such as substance abuse, mental health issues and fear of open drug use worsen when sentenced to prison time. Peer clinical adviser Guy Felicella told the New York Times, “Arresting me and incarcerating me for all those years for using drugs never stopped me once from using drugs — even when I went to prison. It didn’t do anything except create stigma and discrimination, shame,” which is the exact thing Canada is trying to end through decriminalization.

Hoping to reduce the stigma surrounding drug use that leads to deaths due to fear of judgment and sequentially more dangerous usage, Canada is waiting to see how this exemption in 2023 will reduce rates of drug-related deaths, and whether further decriminalization is needed.

To Get Involved:

The Canadian Drug Policy Coalition (CDPC) is an advocacy organization that is fighting against the harm caused by drug prohibition laws. Campaigning with a platform centered on decriminalization, the Coalition strives to reduce the high rates of drug overdose deaths in Canada. To learn more about the CDPC’s mission and to support their work, click here.

Ava Mamary

Ava is an undergraduate student at the University of Illinois, double majoring in English and Communications. At school, she Web Writes about music for a student-run radio station. She is also an avid backpacker, which is where her passion for travel and the outdoors comes from. She is very passionate about social justice issues, specifically those involving women’s rights, and is excited to write content about social action across the globe.

Why Creating Rock Cairns is Dangerous and Wildly Illegal

Amplified by the social media trend of making and photographing these little towers, the prevalence of man-made rock cairns has reached an all-time high. But the illegal practice poses serious dangers to the surrounding environment.

Read MoreThe San Blas Islands, Panama. Whl.travel. BY-NC-SA 2.0

8 Central American Islands You May Have Never Heard Of

Known mostly to locals and frequented by few travelers, these islands have an expansive amount of marine life and culture. This list includes islands in Belize, Honduras, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama.

1. Glover’s Reef Atoll

Belize

Opened to only a few visitors at a time, this 9-acre island is surrounded by Glover’s Reef—a 90 square mile stretch of reef made up of 700 individual patch reefs in a lagoon. This reef is thought to be the richest marine environment in the Caribbean Sea. There are many things to do on the island, such as kayaking, snorkeling, attending a yoga retreat or just relaxing. Once frequented by pirates, this protected marine reserve has been a designated World Heritage Site since 1996.

2. Isla del Caño

Costa Rica

Isla del Caño, Costa Rica. Chris Varley. CC BY-NC 2.0

During pre-Columbian times, this island was a cemetery and home to Indigenous cultures. Located just 10 miles off the Osa Peninsula, it is a protected biological reserve surrounded by five platforms of low coral reefs. It is also home to an abundance of marine life, including sharks, whale sharks, dolphins, moray eels, sting rays and a variety of tropical reef fish. There are no hotels or guesthouses on the island; staying overnight is not allowed.. There are many tours available right outside of the Ballena Marine National Park. Your day trip or overnight stay can begin at the Osa Peninsula, Uvita or Sierpe.

3. Hog Islands

Honduras

Cayos Cochinos a.k.a Hog Islands, Honduras. Bodoluy. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Off of the northern mainland coast of La Ceiba in Honduras lie the Hog Islands, known in Spanish as Cayos Cochinos. They consist of two small islands and 13 tiny sand cays. It’s inhabited by the Garifuna people, and they are the only ones allowed to fish the waters. The islands are managed by the Cayos Cochinos Foundation; they work in unison with the Honduran government and the Garifuna people to preserve the water’s health. The smaller of the two islands is used exclusively as a center for scientific investigation. Cayos Cochinos is a Marine Protected Area (MPA), which includes part of the world's second largest coral reef system known as the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef.

4. Isla Guadalupe

Mexico's Baja Peninsula

Isla Guadalupe. StJenna. CC BY-NC 2.0

The remote volcanic island of Isla Guadalupe, which is Spanish for Guadalupe Island, is located off the west coast of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. The island is home to elephant seals and Guadalupe seals and is inhabited by scientists, military personnel operating a weather station and a small group of seasonal fishermen. The waters surrounding Isla Guadalupe drive experienced divers to take in the views of underwater life; it is known to consistently outperform South Africa and Australia with shark-seeing consistency. The diving tours leave the ports of Ensenada and San Diego and last on average five days.

5. Isla Ometepe

Nicaragua

Isla Ometepe Sunset. Katie Laird. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Located southwest of Lake Nicaragua, Isla Ometepe is home to twin volcanoes: Concepción and Maderas. The island is inhabited with dense forests, natural springs, lake views and hiking trails. There are also diverse plant and animal species, including white-headed capuchins, yellow-naped Parrots and guayabón fruit trees. The island is visited by backpackers and nature seeking enthusiasts, with locals sharing that more eco-tourists are arriving. The best time to visit is during the dry season, which runs from November to April. In the dry season, the butterfly garden is open in Charco Verde, the ecological reserve.

6. Little Corn Island

Nicaragua

Little Corn is the smallest of the Corn Islands off Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast. Once ruled by the British, this remote island produces coconut oil, lobsters and shrimp and is inhabited by roughly 850 people. There are no cars, golf carts, motorcycles or an airport. Seeing the island is possible, but requires two or more connection flights, as well as a 30-minute boat ride from Bluefields, Nicaragua. It’s visited by many who enjoy diving due to the hundreds of dive spots that surround the island. Featuring cheap dining prices, a beer on the island is less than a dollar, and a fresh caught lobster dinner is on average $12.

7. Islas Zapatillas

Panama

Isla Zapatilla. Michael McCullough. CC BY 2.0

Islas Zapatillas or Little Shoes Cays (named for their resemblance to footprints) are two small islands in Bocas del Toro, Panama. The islands are inhabited by sloths and protected by the Bastimentos National Marine Park. Islas Zapatillas are important ecological sites for the endangered hawksbill sea turtles that nest on their shores. You can explore the island through a tour or by charting a private boat to have a more intimate experience. The island is uninhabited, so making sure you have enough water, food, sunscreen and all other necessities is key to enjoying yourself here.

8. San Blas Islands

Panama

San Blas, Panama. Rita Willaert. CC BY-NC 2.0

The San Blas Islands are located in the Caribbean Sea off the coast of Panama. The Kuna Tribe of Panama inhabit the islands and have strictly controlled development and tourism here. All of the money spent on the islands falls directly into the hands of the Kuna Community. Day trips are available, but if staying overnight is an option you’d like to explore, palm-thatched cabins with a sand floor are available. They also offer overwater bungalows or even options for camping. There are visitors who decide to experience the Kuna lifestyle and culture; in those cases, they organize to stay in a dorm of a Kuna family. The island is filled with water activities and scenic views. However, researchers claim that the islands are at risk of disappearing in a matter of decades due to erosion and poor resource management.

Jennifer is a Communications Studies graduate based in Los Angeles. She grew up traveling with her dad and that is where her love for travel stems from. You can find her serving the community at her church, Fearless LA or planning her next trip overseas. She hopes to be involved in international humanitarian work one day.