Morocco is a heady mix of languages, cultures, religions, ancient traditions and modern sensibilities.

Read MorePride and Punishment: The Struggles of the LGBTQ+ Community of Africa

In 32 African countries, homosexuality is deemed unlawful—punishable by imprisonment and in some cases, death. The LGBTQ+ community is fighting prejudice in a battle to be their truest selves.

Ugandan citizens at a pride parade. Chrisjohnbeckett. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Out of the 54 countries that make up the African continent, 32 of them outlaw homosexuality. Historically a continent that traveling members of the queer community steer clear of, Africa has a deep and intricate history with politics surrounding sexuality. However, Africans who identify with the LGBTQ+ community fight fiercely to change legislation, stigma and prejudice in their respective countries, challenging this lineage of controversy. Those who are brave enough to protest for their rights to love whomever they desire organize in-person parades and protests, while those under threat of harm—or even death—find ways to demonstrate their pride in, generating virtual communities and workshops that allow for the LGBTQ+ community to connect across the globe without leaving the safety of their homes.

Map of African countries with anti-gay laws. Amnesty International. CC BY-ND

To understand the hardships facing the LGBTQ+ community of Africa today, it is important to know the causal factors that led to such a homophobic climate. Anti-queer sentiments were introduced to the continent during Western colonization; previous to imperialism affects on the continent, African tribes in many regions practiced homosexuality freely. Val Kalende writes in The Guardian that “there is ethnographic evidence of same-sex relationships in pre-colonial Africa.” This cultural history also demonstrates the lack of importance placed on strict gender roles.

Additionally, the evidence also shows the practice of choice-based pronoun usage; women in positions of power would occasionally label themselves with male pronouns. Post-colonization laws that targeted the cultural muting of African traditions and practices formed the foundations for homophobia by outlawing same-sex relationships and visibly impacted African sentiments around the LGBTQ+ community for the foreseeable future.

Now, on the foundations of decades of hatred inspired by colonizers and imperialists, queer citizens of countries throughout Africa struggle under harsh legislation to simply be their truest selves. In most of the 32 countries that outlaw same-sex relationships, legislation punishes queer people by prison time and fines. Financial punishments vary in size and currency depending on the country. Prison sentences also range widely, varying anywhere between one year (as demonstrated in Ethiopia’s legislation) and lifetime imprisonment (such is the law in Kenya).

There are four countries in Africa that make same sex relationships punishable by death: Mauritania, Somalia, Nigeria and South Sudan. In Nigeria, a country ranked by Forbes as #1 in “The 20 Most Dangerous Places for LGBTQ+ Travelers,” members of the LGBTQ+ community who are found out be participating in homosexual relationships face death by stoning.

LGBTQ+ activists hanging signs. Distelfliege. CC BY 2.0.

Despite the gravity of the punishments for being queer, brave members of the LGBTQ+ community continue to demonstrate their pride. Unwilling to be silenced, queer people all around Africa organize pride parades, protests and online conferences to discuss ways they can fight the systemic homophobia they face in legislation. Further, the same people work hard to destigmatize same-sex relationships, challenging the post-colonial homophobia that has overpowered the original nature of African culture.

Groups like PRIDE OF AFRICA (POA) organize yearly events to celebrate pride, inviting and encouraging queer Africans to “live their most authentic selves.” POA also founded the Johannesburg Pride Parade in 2019, which has recently gone online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but continues to invite members of the LGBTQ+ community to speak and rally. POA also holds online conferences, so those who wish to stay at home and stay anonymous can do so to limit the threat of prejudicial punishments.

For activists in imminent danger should their sexuality be outed, their protesting and pride demonstrations are more closely guarded. For those who need to seek exile in other countries or continents after being unexpectedly outed, journalism, photography and participation in parades like UK Black Pride (which focuses on Pride in the Black community and is based in London) are their only options to avoid death while still being able to demonstrate their pride.

To Get Involved

There are a handful of organizations centered on the eradication of hate crimes, stigmatization, improper health care and prejudicial legislation that accept donations to support their missions. Organizations like OUT that support the destigmatization of queer lifestyles and SHE (Social, Health and Empowerment Collective) specifically serve the African queer community. To find a collective list of legitimate organizations including OUT, SHE, and other foundations actively assisting the LGBTQ+ community of Africa, click here.

POA and UK Black Pride serve the same purposes: to allow for queer Africans to have a safe place to demonstrate their pride. POA takes place mostly online and in South Africa, and UK Black Pride is held in London.

To learn more about POA events, mission statements, and goals, click here.

To learn more about the UK Black Pride Parade and their mission statements, click here.

Ava Mamary

Ava is an undergraduate student at the University of Illinois, double majoring in English and Communications. At school, she Web Writes about music for a student-run radio station. She is also an avid backpacker, which is where her passion for travel and the outdoors comes from. She is very passionate about social justice issues, specifically those involving women’s rights, and is excited to write content about social action across the globe.

6 Things to Know About Kilimanjaro From a Past Climber

Tanzania is home to the tallest mountain in Africa, Mount Kilimanjaro. However, here are six things everyone should know before deciding if they are ready to brave the mountain.

Mount Kilimanjaro. Gary Craig. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Mount Kilimanjaro was created by three volcanic cones called Kibo, Shira, and Mawenzi about 2.5 million years ago. Standing at 19,341 feet, it is home to almost every ecological system: cultivation, forest, heather-moorland, alpine desert, and arctic summit zones. Climbers pass through each of these ecosystems in stages based on elevation. What many may not realize is that Kilimanjaro is dormant, not dead. This means the dormant Kibo cone could erupt again.

I made the climb in January. I will be extremely honest; it was quite miserable at times. It is simply impossible to put into words what hiking a mountain like that will do to you. From the daily struggles of altitude sickness and the feeling of breathing almost nonexistent air, to being the most exhausted you have ever been in your life, dehydrated, starving but unable to keep food down, to having to use the “bathroom” behind a rock right on the side of the trail. I even saw someone lose their life from cardiac arrest. Though it is, thankfully, not a common occurrence, it was rough.

With that said, the struggles make the reward that much sweeter. When I reminisce on my experience, I remember the hard times, but the beautiful moments I was fortunate enough to be a part of are more prominent. The dance and guitar sessions the group would have on our breaks, the feeling of being in a place completely isolated from the world, climbing higher than the plane that got me there, finding a new strength in myself that otherwise would have remained unknown. Kilimanjaro is a monster mountain, but it was the best experience of my life.

1. “Pole, Pole” are words to live by

“Pole, pole” translates to “slowly,” and I cannot stress enough how important this simple phrase is. It doesn’t matter what your physical abilities are, if you do not take your time, you will be hurting. Taking at least five days (depending on your route), this hike is no joke. It’s important to put your pride aside and accept that you might not be the fastest person to get up the mountain, and that’s completely OK! This was something I quickly learned. On the first day, I tried keeping up with the front of my group and very quickly learned I simply wouldn’t make it all six days if I kept that up. No matter what your pace, a guide will always stay by your side, carry things for you if you are struggling, and motivate you to keep going. Guides want you to succeed just as much as you want to, so definitely listen to their advice. They’re lifesavers—literally!

2. You will create amazing connections with your guides and porters

Photo taken by John Willard, my guide on my Kilimanjaro hike.

Your team on Kili will be absolutely amazing, no doubt about it. They will do whatever they can to help you summit, practically carry you if need be. They are extremely selfless and charismatic people, and they make the experience so much more enjoyable. Porters are the men and women who dedicate themselves to carrying all of your gear up the mountain, setting up camp, cooking meals, and creating a vibrant hike experience. Guides spend time with you on your hike—helping you stay on the trail, keeping an eye on your health, and really just guiding you to the summit. On my trip, the team loved to dance and sing and always invited us to join them on breaks and when at camp. They welcomed us to become immersed in the culture and understand the historical importance of Mount Kilimanjaro. The guides and porters truly enhanced the experience, so much that you simply won’t want to leave them. You will want to have WhatsApp downloaded on your phone so you can put in your favorite porters’ and guides’ numbers; when you get home, having those connections will keep a piece of Kili in your heart forever.

3. You will probably get sick

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but if you decide to climb Kili, you will most likely find yourself experiencing at least some altitude sickness symptoms. It’s inevitable when going up 19,000 feet. Headache, nausea, and exhaustion are some of the more common symptoms. They will not end your hike early, but they will make life a little more miserable on the mountain. You just have to push through! Your guides will keep track of your vitals every day and will encourage you to eat and drink as much as your body will allow—food and water will be your best friend up there. You may hear people say that getting to high elevations eliminates your appetite, and this is very true. I found it hard to stomach even soup broth on my hike. It is best to pack some of your favorite snacks to help get past your lack of appetite. Many people, including myself, take altitude sickness pills to help combat symptoms. They are worth taking as long as they don’t cause negative effects on your body. They helped lessen the severity of my symptoms.

4. It is like being in a movie

Aerial View of Mount Kilimanjaro.Takashi Muramatsu. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Kilimanjaro is absolutely breathtaking. I remember feeling like I was living in a Star Wars scene for the majority of the hike. The sunsets and sunrises are unlike anything you will ever see again. Barranco Camp, where you will find yourself after hiking from Shira to Lava Tower to Barranco, was the highlight of my entire hike. Beautiful waterfalls, camping on a cliff in the clouds, being surrounded by the massive Barranco Wall (which you will be climbing up the next morning)—it is a beautiful and untouched part of the world. It makes the everyday battle worth it. When you’re feeling like giving up, just stop and turn around. The view you see will give you the courage to keep going.

5. You may see some horrific things

Barranco Wall on Mount Kilimanjaro. Haleigh Kierman

This is not a guarantee, but it is best to know what can happen. During my hike, I witnessed a man pass away right on the trail from cardiac arrest. I never thought I would see something like this, so it is important you know that really anything is possible before deciding if the hike is right for you. It is much more common to see people get physically sick or use the “bathroom” in clear sight, which are things we can typically move on with. With that said, there is always the possibility you can see something more severe. Do not fear though, Kilimanjaro is remarkably safe given its size. Around 30,000 hikers attempt each year with only a 0.03% death rate. If you know and trust your individual abilities and health, there is little to be concerned about.

6. You will discover an unimaginable amount of self-pride when you finish

Sunrise on Summit Day. Haleigh Kierman

Summit day: it’s killer. You begin the final trek to the summit around 11:30 p.m. and get to the top around 8 a.m., depending on your pace. At this point, you will be sleep-deprived, feeling as though you are suffocating with every step you take because the air is so thin. But somehow, you will find that strength in you to keep going. And when you finally make it to the top, all you will feel is euphoria. You may even shed a tear or two. Kili will push you to your limit and then past that. You really will discover a new part of yourself you didn’t know was there. If you set your mind to conquering Kilimanjaro, you can do it. It will be one of the hardest things you will ever do, but the reward is a feeling of accomplishment that will change your life forever.

Haleigh Kierman

Haleigh is a student at The University of Massachusetts, Amherst. A double Journalism and Communications major with a minor in Anthropology, she is initially from Guam, but lived in a small, rural town outside of Boston most of her life. Travel and social action journalism are her two passions and she is appreciative to live in a time where writers voices are more important than ever.

VIDEO: Mama Rwanda

Located at the converging point between the African Great Lakes region and East Africa, the Republic of Rwanda is an environmentally, economically and culturally diverse country rebuilding its identity in the wake of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, in which approximately 800,000 Tutsis were killed by Hutu extremists. The country takes pride in its regional fauna, which includes elephants, gorillas, hippos, giraffes and zebras. Travelers interested in viewing Rwandan wildlife can observe it in three national parks: Volcanoes National Park, Nyungwe Forest National Park and Akagera National Park. “Mama Rwanda” also shows Kigali, the capital of Rwanda and the heart of its economic and cultural life. The city boasts a vibrant marketplace and architecture that combines traditional and modern styles. Outside the city, Rwanda’s expansive coffee growing fields are tended by over 450,000 planters. Basket weaving has been an important aspect of Rwandan culture for centuries and is now being used by women impacted by the Rwandan genocide to pursue greater economic independence as producers within an international market. Hutu and Tutsi women have come together to weave baskets, a practice that is now a symbol of national reconciliation. These businesses sell their wares to both small stores and large department stores like Macy’s. The profits of weaving companies are often used to support Rwandan families in need of food and medicine.

8 Only-in-Madagascar Experiences

You may know about lemurs and baobabs, but here are more amazing and unique cultural and wildlife experiences that the island nation of Madagascar has to offer.

Sand Mining Threatens Coastline as Sierra Leone Rebuilds

Within a few miles of Sierra Leone’s capital, sand mining is having a devastating effect. As beaches slowly disappear, so do the country’s hopes of post-war revival.

Freetown Beach in Sierra Leone, Erik Cleves Kristensen, CC BY 2.0

Twenty years after Sierra Leone's 11-year civil war, the economic promises of sand mining prove to be costly. The war, which took thousands of lives and led nearly half the country's population into poverty, destroyed most of the country. What followed was a construction boom made possible by an essential ingredient of modern civilization: sand. However, as Sierra Leone’s 300 miles of glorious beaches slowly disappear, so does the revival of tourism and the protection of 55% of the population who live along the country’s coast from the dangers of rising sea levels due to climate change.

As part of a post-civil war move to help communities benefit from local resources, Sierra Leone’s central government gave regulation of sand mining to local councils. Under the 2004 Local Government Act, local committees operate the trucks and strictly hire local people to mine the sand. After a long day of mining, the sand is dried and sold to developers to pave and extend roads as new homes, hotels and restaurants go up across the country.

Government officials defend sand mining as an essential source of jobs and a necessary component in rebuilding Sierra Leone. Kasho Cole, chairman of the Western Area Rural District Council, told the Los Angeles Times that his council is “sensitive to environmental concerns, having banned sand mining on certain beaches because of the devastation it has already caused.”

Cole also acknowledged that assessments had not been carried out anywhere in the district to determine sand mining’s environmental impact. Due to large-scale illegal sand mining operations, Cole could not provide a definite amount of sand extracted from the beaches.

Sand theft, the unauthorized and illegal form of sand mining, has led to a worldwide non-renewable resource depletion issue, causing the permanent loss of sand and significant habitat destruction. Sand mining has already made a significant environmental impact in North Stradbroke Island and Kurnell in Australia; the Indian states of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Goa; and the Red River in Yunnan, China.

In the United States, the sand mining market generates slightly over $1 billion per year. The industry continues to grow annually by nearly 10% because of its use in hydrocarbon extraction. Globally, sand mining is a $70 billion industry, with sand selling for up to $90 per cubic yard.

In Sierra Leone, sand mining operations are regulated on John Obey Beach, a village 20 miles south of the Western Area (Freetown Peninsula.) According to the Environmental Protection Agency, sand mining should be banned on all beaches apart from John Obey. However, when the police leave the beaches at 5 p.m., the mining continues after dark.

Efforts to address the issue are hampered by conflicts of interest from those involved: miners who need the work, construction companies who need the supply and investors who are getting rich taxing the sand. Last year, a press statement from the local police force confirmed “certain service personnel appear to be aiding and abetting this illegal act.”

As dump trucks continue to haul sand away and tides push further inland, John Obey Beach is slowly disappearing—taking trees, businesses, homes and dry land with it as far down the coast as Bureh, a surf town two miles south. While the activity contributes to Sierra Leone's coastal erosion, which is proceeding at up to 6 meters a year, the removal of sand also changes wave patterns that move sand along the coast, altering the quality of surf that Bureh, a renowned surf spot in Africa, is known for.

Prior to the war, Sierra Leone’s beaches were packed with adventurous travelers from around the world. Kolleh Bangura, the director of Sierra Leone’s Environmental Protection Agency, told The New Humanitarian that “sand-mining is a calamity for the tourism industry… Anywhere in the world, sand is the resource of tourism, but now our beaches are being degraded.”

Lakka, a coastal town located 10 miles from Freetown, was once known for its large beaches and seaside resorts, offering a glimpse of the future if actions are not taken. Sand mining on Lakka Beach is illegal now, but the ban came too late—leaving a thin wedge of sand lined by crumbling buildings, many of which have been left abandoned.

Even the miners themselves recognize sand mining is not sustainable; however, with a youth unemployment rate of 70%, the pressure falls on the government to provide alternative jobs. “In time, they need to ban it, as we want to bring tourism here,” Abu Bakarr, a sand miner, told The New Humanitarian. “But we need sand-mining to sustain our lives…The government needs to give us jobs. If there are no jobs, the youths will mine the sand.”

Papanie Bai-Sessay, the biodiversity officer at Conservation Society of Sierra Leone, told the Los Angeles Times that “the sand has been a buffer… we are destroying our first line of defense. If we don’t stop, it will be a disaster for millions.”

Claire Redden is a freelance journalist from Chicago, where she received her Bachelor’s of Communications from the University of Illinois. While living and studying in Paris, Claire wrote for the magazine, Toute La Culture. As a freelancer she contributes to travel guides for the up and coming brand, Thalby. She plans to take her skills to London, where she’ll pursue her Master’s of Arts and Lifestyle Journalism at the University of Arts, London College of Communication.

VIDEO: Growing Up in a Megaslum in Kenya

Joseph Djemba grew up in Kibera, Kenya, the largest urban slum in Africa. Djemba found himself there when his mother became unable to support her eleven children after the death of her husband. Djemba describes his childhood sleeping outside and begging for food, detailing the psychological impacts of living in poverty. He also notes the large gap between the rich and the poor in Kenya and discusses how impoverished people help each other survive. Djemba is the main character in “Megaslumming,” a book by Adam Parsons. In his work, Parsons explores how the settlement of Kibera came into existence and documents what life is like for those who live in slums.

Get Involved:

Touch Kibera Foundation is a non-profit organization devoted to uplifting children who live in Kibera, Kenya through sports programs, sexual health programs, education support and mentorship opportunities. Donations are accepted online, and more information can be found here.

Polycom Development Project is a foundation which seeks to provide educational and athletic opportunities to girls and women in Kibera. The organization is also devoted to promoting sanitation and public health. Donations are accepted online, and more information can be found here.

St. Vincent de Paul Community Development Organization aims to provide support to orphaned and other vulnerable children in Kibera. The organization supports families and seeks to intervene on behalf of children at an early stage in their development. Donations are accepted online, and more information can be found here.

PHOTO ESSAY: Child Marriage in Ethiopia

While it may seem shocking, in Ethiopia girls are married off at ages as young as 5 years old, and 48% of rural women are married before age 15. Photographer Guy Calaf documents these young child brides and their marriages in this photo essay.

Read MoreLike so many others across the country, this village in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley blends seamlessly into its colorful surroundings. Rod Waddington. CC BY-SA 2.0

Top 5 Sites to Visit in Ethiopia, Africa’s Hidden Gem

Boasting a stunningly diverse landscape, a rich culture and nine UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Ethiopia belongs on every traveler’s bucket list. As word gets out, more and more visitors are discovering – and falling in love with – the East African country’s seemingly endless charms.

Seen from above, the Church of Saint George looks impressive. From below, it’s simply unreal. Bryan_T. CC BY-ND 2.0

Lalibela

Painstakingly chiseled out of rock in the 13th century, the 11 churches of Lalibela stand as powerful symbols of Ethiopia’s devotion to Christianity. After Jerusalem’s fall to Islamic conquest, King Lalibela ordered construction of a “New Jerusalem” in his own land. The results are spectacular: the Church of Saint George rests in the shape of a cross, seemingly inaccessible due to its position below ground. It’s nearly incomprehensible that the churches of Lalibela were carved out by hand 800 years ago. You may come to believe, as many locals do, that angels alone could have built such a masterpiece.

The Simien Mountains, often known as the “Water Tower of Africa,” are one of the top contributors to the Nile River. Thomas Maluck. CC BY-ND 2.0

Simien Mountains National Park

Known as the “Roof of Africa,” the Simien Mountains present a landscape of sheer cliffs, winding canyons and peaks once described by Homer as the “chess set of the gods.” Few places in Africa offer such breathtaking scenery; however, travel here takes some work. To fully experience the Simiens, prepare for long days of trekking and nights spent in remote villages. The trip may be tough, but travelers who persevere can expect jaw-dropping scenery unlike anywhere else on earth.

Eerily similar to the mazelike medinas of North Africa, Harar holds no comparisons across Ethiopia. Rod Waddington. CC BY-SA 2.0

Harar Jugol

Considered the fourth-holiest city of Islam, Harar gives off a distinct vibe from the rest of Ethiopia. Visitors head to Jugol, the fortified city, to take in the area’s maze of 368 alleyways and 48 mosques – all packed into less than a half a square mile.

Sulfur pools are one of the many anomalies that draw visitors to the harsh landscapes of the Danakil Depression. Ian Swithinbank. CC BY-ND 2.0

Danakil Depression

Lying 400 feet below sea level and recognized as one of the hottest places on earth, the Danakil Depression is downright inhospitable. Scientists flock to the region to test out whether microbes can survive the environment, believing its harshness to be about equal to that of Mars. Visitors are equally enticed by the Danakil Depression’s otherworldliness, seeking out neon-colored lakes, steaming fissures and bubbling lava patches. Travel to the area is not for the faint of heart; daytime temperatures reach up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit and the condition of the “roads” is equally hideous.

Nearly anything can be found at the Mercato, the largest open-air market in all of Africa. Jasmine Halki. CC BY 2.0

Addis Ababa

Ethiopia’s capital and largest city may not hold many star attractions, but nowhere else does the country’s culture so vividly come to life. Indulge in a cup of coffee in one of Addis Ababa’s countless cafés; this is, after all, the birthplace of the drink. Lucky visitors may receive an invite to an Ethiopian coffee ceremony, a tradition that lasts for hours and is reserved for close friends. Addis also contains some of Ethiopia’s best food. Make sure to try injera, a spongy bread filled with meat, vegetables and countless spices. Finish off the stay by visiting the Mercato, Africa’s largest open-air market. A dizzying array of gifts can be found, helping to carry the delightful essence of Ethiopia all the way home.

Stephen Kenney

Stephen is a Journalism and Political Science double major at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He enjoys sharing his passion for geography with others by writing compelling stories from across the globe. In his free time, Stephen enjoys reading, long-distance running and rooting for the Tar Heels.

Saving More Elephants with Honey than with Vinegar

The vast majority of people around the world have only seen African elephants from a television screen, from behind fences in zoos, or- if they’re lucky- from a safe seat in a safari car as it bounces past the grazing giants of the Serengeti. From those vantage points, it’s impossible to look at the massive bodies, dexterous trunks, and intelligent eyes of the elephant and not feel a keen sense of wonder and awe. Elephants are some of those ‘charismatic megafauna’ that capture the hearts of people worldwide, making conservation efforts seem like a no-brainer. Who wouldn’t want to protect and save these wise, complicated, prehistoric-seeming creatures?

The people who share a homeland with elephants might be in that category.

Elephants are herbivores, and must eat almost constantly to maintain enough calories to support their gargantuan bodies- individual adults can consume between 200 and 600 pounds of food per day. Traveling in family groups that can consist of 10-20 elephants or more, that’s an incredible amount of vegetation needed to sustain a herd.

In addition to the grasses, roots, fruit, and bark found in the wild, elephants have quickly learned that their human neighbors can provide a tasty supplement to their diet- fields of carefully tended yams, cassava, corn, plantains, and grains. A herd of elephants can destroy a subsistence farmer’s means of food and income for the whole year in just a single night.

These episodes of crop raiding have created dangerous situations for people living in sub-Saharan Africa. Desperate to protect their livelihood, farmers may try to stay awake all night, ready to yell and bang pots in an effort to frighten away any pachyderm pilferers. However, elephants are not so easily startled by humans, and have been known to attack and kill would-be crop defenders. In anger and frustration, a group of villagers may then retaliate and try to kill the next group of elephants they see. These was creating a vicious cycle of animosity on both sides; elephants are intelligent creatures, and once they began associating humans with pain and disruption, there was evidence that they became more violent to humans in future encounters.

The heightened tensions were disastrous for both humans and elephants, and a solution was desperately needed to protect both vulnerable groups.

There had been local rumors buzzing around for a while that claimed elephants were afraid of bees, but it wasn’t until researchers Fritz Vollrath, Dr. Iain Douglas-Hamilton, and Dr. Lucy King investigated that those results were confirmed to the rest of the world. When confronted with the sound of bees buzzing, the elephants would immediately retreat and send out a rumbling call that would warn other elephants of danger in the area. Additionally, the elephants would begin shaking their heads and dusting themselves, suggesting that their skin was sensitive to bee stings and that they knew to associate the sound with potential pain.

Armed with this knowledge, researchers, nonprofits, and government groups set out to make affordable beehive fences that could protect precious crops from marauding elephants and protect elephants from learning dangerous behaviors that would bring them into conflicts with humans.

In the last few years, as the success of the beehive fences has been proven time and again, they are gaining in popularity throughout Africa. The fences are genius in their simplicity; a hanging box hive is hung from a fence every ten meters, all connected by wire. This way, if an elephant brushes against the fence or wire, the hives will swing and rock and the bees will swarm out to get away from the disturbance. Nearly 100% of the time, the elephant will turn tail and run, warning its family members to stay away. Thanks to their famous memories, the elephants won’t soon forget that lesson.

Not only do the fences allow farmers to harvest their full crop without any losses to elephants, but the honey produced in the hives has also found a niche market. “Elephant-Friendly Honey,” as it’s called, has been a huge hit with globally conscious consumers who increasingly want to know that the products they are buying support a good cause.

African elephant populations have slowly been increasing since the poaching crisis that decimated their numbers in the 1970’s and 1980’s. While the rest of the world celebrated that fact, many African people living in close proximity to elephants couldn’t see why people around the world were so eager to save the creatures that were plaguing their lives and livelihoods. Now, thanks to an increased effort to help protect people along with ivory-tipped neighbors, more and more people are able to view their globally treasured wildlife with a sense of pride instead of fear.

Katharine Rose Feildling

Katharine Rose was born in Maryland and is currently working for the Condor Recovery Project in California. She studied wildlife management in East Africa, and gained a deep passion for wildlife conservation, social activism, and travel while there. Since then, she has traveled and worked throughout the United States, South America, and Asia, and hopes to continue learning about global conservation and inspiring others to do the same.

Child Slavery in Ghana

When Elizabeth Tulsky participated in NYU’s study abroad program in Ghana, she also independently volunteered with City of Refuge, a local organization that uses education as a tool to combat child slavery. She said of her experience that it had “a tremendous impact on my life and what I want to do in the future.”

In Ghana, children are often enslaved, maltreated and many mothers struggle to see their children as more than a financial burden. While there are no statistics on the actual number of children trafficked, estimates are in the thousands. What is known is that 25% of Ghanaian children ages 5-14 years are involved in child labor. Child labor and human trafficking are both against the law in Ghana, however, laws are not enforced.

City of Refuge fights against child slavery by educating small villages about the harms of keeping children out of school and depriving them of a childhood. The organization is founded on the belief that if they can empower single mothers educationally and economically then they will no longer be vulnerable to selling their children as slaves.

Can you tell me a bit about City of Refuge and the work they do?

City of Refuge workers enter villages and open discussions with the chiefs in a respectful manner and work to free children who are in dangerous and/or miserable conditions and separated from their families. On a daily basis, City of Refuge provides home, happiness, and sanctuary to many rescued children. Furthermore, City of Refuge runs the only public school in the city, Doryumu. The organization works at the root of the problem, beginning with single mothers. Many children end up in slavery because mothers simply have absolutely no means of supporting themselves, much less their young children. Selling them, as hard as it may be to believe, truly seems like the only option for many women. Thus, City of Refuge works with single mothers to find alternative solutions to make ends meet, and have started two local businesses to be run by single mothers to increase opportunities for mothers and in turn, reduce the number of children sold into horrific situations.

How were you involved with the organization?

I worked in the small school where the children living with the City of Refuge family were educated and spent my evenings at the home playing with children and helping them with their homework. I also spent time shadowing the founders and through this I learned much about the process.

What do you know about child slavery in Ghana?

Children are targeted as slaves for fishermen for several reasons. First, children are easy to acquire as so many parents are impoverished and feel financially helpless. Second, children’s small hands are ideal for making and untangling fishing nets. When the nets get trapped in trees in the lake, children are sent in the water to untangle them. Unfortunately, this means many of the child slaves are incredibly susceptible to water-borne disease and illness and sadly, some do not know how to swim and may drown in the water. Children who are enslaved receive no form of education or care and spend up to eighteen hours a day working on the lake. They are often fed no more than one meal a day, which frequently consists of just gari, a food made from cassava, soaked in the lake water.

Any advice for travelers going to Ghana?

This is probably true for every country, but just approach everything with an open mind, try new things, immerse yourself in the culture as much as possible.

How can readers help the victims of Child Slavery in Ghana?

Check out City of Refuge for more information.

Other organizations doing good work include Youth Generation Against Poverty (YGAP), an organization that inspires volunteers through creative fundraising opportunities. They have created several projects partnered with City of Refuge.

Elizabeth Tulsky

Elizabeth studied social work at NYU and has experience working with trauma, grief, family issues, depression, anxiety, ADHD, and general life transitions. She hopes to use her work to create culturally responsive, affirming and inclusive healing spaces while promoting the use of person-centered, strengths-based, trauma-informed, anti-racist and social-justice frameworks.

Mass Detention of Civilians In Ethiopia

The Ethiopian government declared a state of emergency, resulting in the detention of civilians on suspicion of cooperating with rebel terrorists.

Addis Ababa, capital of Ethiopia. DFID - UK Department for International Development CC BY 2.0

Ethiopia has been in the throes of a civil war. The federal government, headed by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, has been fighting against Tigrayan rebels in the northwest region of the country. Recently, it appears Tigray fighters are at an advantage as they push south towards the nation’s capital. In response, the government declared a state of emergency Nov. 2 and began to roundup civilians of Tigrayian descent. Civilians with no connection to the rebels are being detained, forced from their homes, plucked off the street or at work. The United Nations stated that more than 1,000 people have been detained since the government declared the state of emergency. Additionally, they reported that 70 drivers contracted by the United Nations and agencies to deliver aid to the country have been detained by officials as well. Along with the detained drivers, 16 employees of the United Nations were detained following the state of emergency. These employees were present because the Tigray region is in desperate need of aid after airstrikes fell on the region in mid-October. The dire situation in Tigray has been labeled an ongoing humanitarian crisis.

The civil war broke out after tensions between the Tigray’s People Liberation Front political party and the federal government came to a point. The party previously held control of the Ethiopian government for decades, until Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed took office in 2018. In 2020, the T.P.L.F attacked a military base in the Tigray region, prompting the Prime Minister to order a military offensive in response. In June, the Ethiopian military was forced to withdraw from the Tigray region, marking a major defeat and subsequent turning point of the conflict.

In July 2021, the United Nations requested access to the region because an estimated 400,000 people were experiencing famine, with another 1.8 million at risk. Additionally, 1.7 million people have been internally displaced while thousands of others have fled the country.

The state of emergency declared on Nov. 2 allows officials to search anyone’s home and arrest without a warrant solely based on suspicion of association with rebel groups. The recent arrests have included other ethnicities, but the majority of detentions have been people of Tigrayan descent. Along with the large-scale detentions, public figures allied with the government have taken to social media inciting hate speech against ethnic Tigrayans. The head of the Ethiopian government communication office stated that the detentions were not ethnically motivated, but the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights expressed concern at the broad terms of the recent state of emergency.

Dana Flynn

Dana is a recent graduate from Tufts University with a degree in English. While at Tufts she enjoyed working on a campus literary magazine and reading as much as possible. Originally from the Pacific Northwest, she loves to explore and learn new things.

The World’s Electronic Waste is Ending Up in Ghana’s Landfill

While new tech gadgets launch every few months, the buildup of electronic waste is being sent to Ghana and damaging the citizens’ health.

Location, Ghana. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

The capital city of Accra in Ghana is home to the largest e-waste landfill, Agbogbloshie. Electronic waste or e-waste is waste material with any battery or power cable. It ranges from everyday appliances to laptops, circuit boards, lamps, phones, etc. If these items are not disposed of properly, they can become harmful to the environment and people. An estimated 250,000 tons of electronics are sent every year to the dumpsite. The site not only houses e-waste, but about 40,000 Ghanaians inhabit the area alongside livestock.

The e-waste arrives in Ghana through the Port of Tema, about 20 miles east of Agbogloshie. Most of the items in the container ships are from the United States or Western Europe. The electronics are secondhand and sent to Ghana with the idea of being refurbished then sold. The majority of the items cannot be fixed and become e-waste, which is then taken to Agbogbloshie. Once the electronics arrive at the dumpsite, there is an entire process the electronics go through. First, small collectors sell the items to scrap dealers known as “masters.” The scrap dealers then have their workers, known as “boys,” use their bare hands, hammers and other tools to break apart the valuable metals inside. At times insulated wires are bundled together and taken to the “burner boys” they’re in charge of burning the plastic off of the wires. In doing so, they’re able to retrieve valuable metals. The metals include copper, aluminum, zinc, silver and others. Once the metals are recovered, they are weighed and sold for instant cash.

PCBs Used to Extract Metals. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

The supply and demand is what fuels the toxic pollution in Agbogbloshie. As soon as the bulk of metals and wires are sold, they are exported out of Ghana and reused to produce new devices. The men and young boys who do this harmful labor are usually from rural northern cities searching for work to provide for their families back home. A “burner boy” will make about $40-50 Ghanaian cedis a day (US$6-8). Living in extreme poverty and barely making enough to move further up the chain, along with paying the ultimate price with their lives. They work arduously with no protective gear and no government regulations. At times, these young men and children have multiple health issues due to the toxic fumes and chemicals that leak from the electric waste. They face chronic nausea, debilitating headaches, skin diseases, burns, respiratory problems, infected wounds and cancer among others. All these issues are brought on by the toxic work environment, pollution and lack of regulations. Most people know that this line of work is debilitating to their health. However, the desperation for survival is the driving force.

The people who work and live in Agbogbloshie are not the only ones suffering; the livestock is, too. The toxins are entering the food chain as cattle roam and graze the dumpsite freely. This is concerning as the Agbogbloshie area is home to one of the largest food markets in Accra. Most of the cows and chickens are slaughtered and eaten by the residents, which then ingest the high-level toxins. In addition, the water is also being contaminated as Agbogbloshie is situated on the Korle Lagoon. This lagoon is filled with piled-up waste of all sorts and links to the Gulf of Guinea, the Northeastern part of the Atlantic Ocean.

Goat Freely Roaming. Fairphone. CC BY-NC 2.0

Agbogbloshie is known to many of the locals as Sodom and Gomorrah. These biblical cities are synonymous with Agbogbloshie’s difficult living conditions. Although harsh, the people of this slum depend heavily on electrical waste in order to make a living. The Ghanian government has condemned the activity that’s taking place here. However, it has not lessened. As of now, change might be taking place in the near future. The German agency, GIZ, is in the middle of delivering a $5.5 million project for the people of Agbogbloshie. The plan is to build a sustainable recycling system and a health clinic and football pitch for workers. Much more will need to be done to keep the people’s health intact and away from this harmful environment. However, this is a start in bettering the status quo.

Jennifer Sung

Jennifer is a Communications Studies graduate based in Los Angeles. She grew up traveling with her dad and that is where her love for travel stems from. You can find her serving the community at her church, Fearless LA or planning her next trip overseas. She hopes to be involved in international humanitarian work one day.

Trekking Up Le Morne Brabant Mountain in Mauritius

This mountain, which serves as a symbol of hope, offers hikers a breathtaking view of Le Morne beach and remains a meaningful part of local Mauritian culture.

Read MoreCongo Couture: “Sapeurs” Bring Europe’s Designer Fashion to Central Africa

The Republic of the Congo’s world-famous fashionistas strut through the streets of Brazzaville wearing outfits from Europe’s most revered designers. But to sapeurs, their fashion savvy is not just style but a lifestyle.

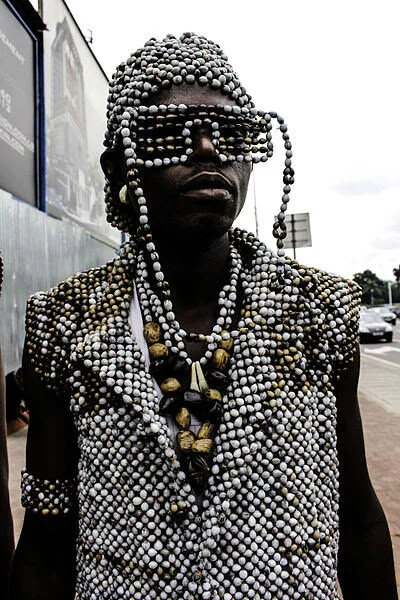

A sapeur in his Sunday best. ilja smets. CC BY-ND 2.0.

Maxime Pivot makes all the ladies scream. Men call him the pride of the town. Children follow him wherever he goes. The Republic of the Congo has never seen a more dashing, debonair, sharp-dressing gentleman. As a modern-day dandy in the streets of Brazzaville, he is a painterly splash of Congo couture amid near-universal penury. He boasts a double-breasted red suit, a pearl-white shirt, pitch-black sunglasses and a pink bowtie, an outfit to amaze the prim and plebeian alike. Rather than envy, his panache inspires pride. Some may call his focus on fashion amid staggering poverty vain, but really, he is preserving a decades-long tradition. He is a sapeur.

That means that he is a member of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes—La Sape for short. In English, it translates to the Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People. Every weekend, he and his fellow dandies meet to compare outfits from the hottest European designers, trade notes on color combinations and revel in the pomp of haute couture. They smoke, they dance and they conversate. They escape the squalor in which so many Congolese live—when sapeurs dress up, they feel like the richest men in the world.

No, they are not rich. Quite the opposite. By day, sapeurs are chefs, mechanics, electricians, craftsmen, businessmen, handymen, journeymen, or any other kind of blue-collar worker. 70 percent of people in the Republic of the Congo live in poverty, and most sapeurs are included in that number. What distinguishes them is not wealth but aesthetic distinction, good taste, and a deep knowledge of the latest fashion trends. They aspire to look like a million bucks, not spend it.

The street is a catwalk. Jean-Luc Dalembert. CC BY-SA 4.0.

The tradition began during the Congo’s colonial period. Congolese servants, tired of wearing their Belgian and French colonizers’ secondhand clothes, began saving their wages and purchasing the latest clothes for European dandies. After serving in the French army during World War II, Congolese soldiers returned home bringing closets-worth of European suits, shirts, ties, shoes and accessories. By the time the central African nation gained independence in 1960, many Congolese elites were making pilgrimages to Paris to rack up designer clothes for their wardrobes back home. Although they were accused of relying on white, “Western” traditions, most sapeurs insist on their artistic independence. As Papa Wemba, one of La Sape’s earliest celebrities, said, “White people invented the clothes, but we make an art of it.”

However, investing in clothes instead of, say, property or livestock can be difficult to justify in one of the poorest parts of the world. Many sapeurs hide their expensive lifestyles from relatives to avoid endangering family ties. If a cousin learns that their family member would rather buy an Armani suit or Weston shoes than help put food on the table, they may feel betrayed and break off relations. Furthermore, the wives of sapeurs tend to bear the brunt of the sapeur lifestyle far more heavily than their husbands, as they suffer the financial cost without being able to revel in high fashion.

European style, African art. Opencooper. CC BY-SA 4.0.

La Sape is overwhelmingly male. Overwhelmingly, but not entirely. As the tradition evolves, more women are staking their claim as sapeuses. They, too, don designer suits from Versace, Dior and Yves Saint Laurent and develop mannerisms and gaits to build a persona around their clothes. Even children are beginning to partake in the sapeur culture. Many worry that Congolese tailors lack apprentices to carry on the tradition, so the sight of a child strutting down the streets of Brazzaville in an Armani suit assures them that the legacy of La Sape will continue.

In fact, Maxime Pivot established an organization, Sapeurs in Danger, to preserve the tradition of La Sape, which he asserts is not just about fashion but also is a way of life. When committing to the lifestyle, sapeurs adopt a code of conduct which Ben Mouchaka, another famous sapeur, summed up in 2000. He calls it the Ten Commandments of Sapeology.

1- Thou shalt practise La Sape on Earth with humans and in heaven with God thy creator.

2- Thou shalt bring to heel ngayas (non-connoisseurs), nbéndés (the ignorant), and tindongos (badmouthers) on land, under the earth, at sea and in the skies.

3- Thou shalt honour Sapeology wherever thou goest.

4- The ways of Sapeology are impenetrable for any Sapeologist who does not know the rule of 3: a trilogy of finished and unfinished colours.

5- Thou shalt not give in.

6- Thou shalt demonstrate stringent standards of hygiene in thy body and clothes.

7- Thou shalt not be tribalistic, nationalist, racist or discriminatory.

8- Thou shalt not be violent or insolent.

9- Thou shalt abide by the Sapelogists’ rules of civility and respect thy elders.

10- Through prayer and these 10 commandments, thou, as a Sapeologist, shall conquer the Sapeophobes.

Maxime Pivot aims to pass down the tradition of La Sape to any man, woman, or child willing to devote themselves to the lifestyle. He operates a school of La Sape where he teaches aspiring sapeurs how to combine colors tastefully and craft a swaggering gait. His classes teach that La Sape needn’t sap their wallets. As the sapeur life and style spread, he hopes that dandies will don local brands, not just expensive European ones.

Innovating a classic style. Makangarajustin. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Then, La Sape could be truly independent from European designers. Fashion trends have been increasingly moving in that direction, thanks to Maxime Pivot’s efforts, especially now that La Sape has moved into the mainstream. Every August 15, the Republic of the Congo’s independence day, sapeurs march alongside the military, indigenous tribes and even the President in the largest parade of the year. Their flashy clothes and sauntering stride draw cheers from the crowd. Their tradition provides an example of how the country can emerge from an oppressive European past and spring into a liberated African future.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

COVID-19 Slows Africa’s Progress Against Poaching

Poaching is a last resort for villagers who lost their jobs due to COVID-19 lockdowns. Conservationists now struggle to preserve endangered species.

A valuable commodity. valentinastorti. CC BY-NC 2.0.

They march through the field with chainsaws, the rhinos sedated. What follows is no gruesome act of poaching. It’s the exact opposite. Workers at the Spioenkop Nature Reserve in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province rev their chainsaws and go to work sawing off the rhino horns. “It has a face mask put on it to cover its vision, it has earplugs put into its ears [...] so that reduces trauma to the animal,” says Mark Gerrard of Wildlife ACT, a nonprofit that protects African wildlife. “We’ve got to remind ourselves that this [a rhino’s horn] is just keratin—this is really just fingernails.”

These rhinos’ horns will grow back in 18 to 24 months, but in the meantime, poachers won’t hunt them for the priceless commodity. Armed with only chainsaws and sedatives, the conservationists at the reserve are combating Africa’s interminable poaching problem. If a rhino has no horns, poachers have no reason to kill it. This fact doesn’t make the job any easier. “It is a traumatic experience for us,” Gerrard says, “not for the rhino.”

Spioenkop Nature Reserve has fared unusually well in its fight against poaching. Out of 15,600 rhinos in South Africa, 1,175 were killed by poachers in 2014. In 2015, the country began dehorning rhinos to considerable success. By 2019, the number of dead rhinos had fallen to 594. By 2020, it was 394. Nevertheless, Gerrard defines a truly successful dehorning effort as “zero animals poached.”

Two big cats, two big trophies. DappleRose. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

It will be a hard goal to reach. After COVID-19 effectively shut down international travel, tourism revenue in Africa plummeted, leaving conservationists cash-strapped in their anti-poaching campaigns. Spioenkop Nature Reserve has struggled to patrol its vast territory, but the issue goes beyond just South Africa. Wildlife tourism generates $29 billion each year and employs 3.6 million workers across Africa. The lack of sufficient funds for anti-poaching efforts is a continent-wide problem.

In Zambia’s Kafue National Park, poaching takes place at the edges of the park, where patrols have been cut back. In 2020, the park reported a 170% increase in snares, which snag wild cats. That same year, two lions were killed while none had been slain the year before. More disconcerting, patrollers increasingly find poached animals gored for “buck meat.” Poor local villagers, desperate from COVID-19 lockdowns, have joined poachers in the hunt to earn a living and put food on the table.

By and large, however, poaching is the work of international crime syndicates working in the black market. Some conservationists advocate legalizing the sale of poached items such as rhino horns and ivory to lower the market value, reducing profits for poachers. In Kenya, courts have buffed up their prosecution efforts, leading to a precipitous drop in poaching. Dedicated legal teams actively pursue convictions for poaching, and those caught red-handed face long prison sentences and fines of up to $200,000. Still, the black market provides lucrative opportunities for locals willing to break the law in hopes of amassing a fortune. A 35-pound black rhino horn can be worth up to $2 million. For poor Africans, the opportunity is often irresistible.

Confiscated rhino horns. USFWS Headquarters. CC BY 2.0.

At Mpala, a research center in central Kenya, patrols have adopted a digital approach to combat rampant poaching. They use the SMART app (spatial monitoring and reporting tool) to track every animal a patrol encounters—alive or dead. It also allows them to track people seen infiltrating the parks. Conservationists are attempting to make up in brainpower what they lack in manpower; less tourism revenue led to slashed budgets, which meant fewer patrols. However, park managers agree that addressing the root cause of poaching, poverty, is the best solution to the problem. In this regard, nobody seems to have an answer.

So the traumatic work of sawing off rhino horns in Spioenkop continues. “We cannot let our guard down,” says Elise Serfontein of the organization Stop Rhino Poaching. “The kingpins and illicit markets are still out there, and even losing one rhino a day means that they are chipping away at what’s left of our national herd.” With one rhino’s horn sheared to a nub, the team moves on to the next. The rhino sleeps in the field as they approach. One member revs the chainsaw and begins cutting. White flakes flutter through the air like dust.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.

LGBTQ+ Intolerance in Ghana Reaches Boiling Point

Tensions within the West African country have risen following the recent restriction of LGBTQ+ rights, resurfacing the decades long discussion regarding the criminalization of same-sex conduct.

Pride flag waving in the sky. Tim Bieler. Unsplash.

The newly established office of nonprofit organization LGBT+ Rights Ghana was raided and searched by police last month, endangering one of the only safe spaces for LGBTQ+ people in the country. This raid came mere days after Ghanaian journalist Ignatius Annor came out as gay on live television, and many have speculated that the raid was in retaliation of that moment.

Given Ghana’s criminalization of same-sex conduct, it is not a stretch to say that homophobia runs rampant and unchecked, especially when considering the widespread opposition from both government officials and religious figures regarding the construction of the center for LGBT+ Rights Ghana.

The building has been under scrutiny since it first opened back in January. Only three weeks after opening its doors to the public, the organization had to temporarily close in order to protect its staff and visitors from angry protesters. The director of the organization, Alex Kofi Donkor, explained how the community “expected some homophobic organizations would use the opportunity to exploit the situation and stoke tensions against the community, but the anti-gay hateful reaction has been unprecedented.”

This unprovoked suppression of basic freedoms indicates that LGBTQ+ intolerance in Ghana has reached a boiling point and is about to bubble over.

Aerial shot of Accra, Ghana. Virgyl Sowah. Unsplash.

News of the situation reached a handful of high-profile celebrities such as Idris Elba and Naomi Campbell, who joined 64 other public figures in publishing an open letter of solidarity with the Ghanaian LGBTQ+ community using #GhanaSupportsEquality. While prejudice has only recently garnered public attention due to the letter, blatant and widespread homophobia in Ghana has run rampant for years.

According to a study conducted by the Human Rights Watch in 2017, hate crimes and assault due to one's sexual identity are regular occurrences in Ghana. Dozens of people have been attacked by mobs and even family members out of mere speculation that they were gay. Furthermore, the study found that for women, much of this aggressive homophobia was happening behind closed doors through the pressures of coerced marriage.

Consider 24-year-old Khadija, who identifies as lesbian and will soon begin pursuing relationships with men due to the societal pressure for women to marry. Or 21-year-old Aisha, who was exiled by her family and sent to a “deliverance” church camp after she was outed as lesbian.

Marriage pressures and intolerances are certainly prevalent in other countries as well, even in those often deemed progressive. The big difference is that in many countries, homophobic beliefs are slowly becoming less and less common. In Ghana, it seems as though these sentiments are normalized and held by the majority of people.

The precedent for discrimination based on sexual orientation was set as early as 2011, when former Western Region minister Paul Evans Aidoo called for the immediate arrest of LGBTQ+ people in the area. The stigma that actions like this produced in Ghana have only been amplified over time when coupled with religious and cultural tensions.

A rainbow forms above a home in Kumasi, Ghana. Ritchie. Unsplash.

Many victims of hate crimes or abuse in Ghana reported that because of the codified homophobia in the country, they are unable to report their experiences to local authorities without putting themselves in danger. As a result, LGBTQ+ Ghanaians find themselves stuck in a perpetual cycle of making slight progress just for higher authorities to snatch it away.

There have been countless opportunities for legalized discrimination to be addressed, and ever since current Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo assumed office in 2017, he has been under immense pressure to announce his official position on homosexuality. Four years later, he has still not done so.

Instead of embracing the shift toward more inclusive policies supported by LGBT+ Rights Ghana, the Ghanaian government appears to be succumbing to public pressures in an attempt to keep peace. What it fails to realize is that sweeping inequalities under the carpet doesn’t make them go away. It actually does quite the opposite. It heightens inequalities until they become absolutely impossible to avoid. Celebrity involvement in dismantling Ghana’s current system has caused quite the public reaction. It may end up being the spark that causes the Ghanaian government to reconsider its policies and begin to offer LGBTQ+ people the respect and protection they deserve.

Zara Irshad

Zara is a third year Communication student at the University of California, San Diego. Her passion for journalism comes from her love of storytelling and desire to learn about others. In addition to writing at CATALYST, she is an Opinion Writer for the UCSD Guardian, which allows her to incorporate various perspectives into her work.

Angola: A Video of Culture, Diversity, and the Lasting Legacy of Civil War

Having been ravaged by civil war from 1975-2002, Angola is a country still reckoning with its complex history. This legacy of colonization means that Angola has had to rely largely on raw natural resources for economic development. However, it’s been slowly stabilizing for the past decade, recovering from its past and getting ready to face the world of today. Although there has been significant strides in modernization, Angola retains much of its cultural and geographic diversity, boasting both crowded cities and remote salt flats and sea cliffs. This video takes you through many different regions of the country, showing the diversity present in both the people and their environment while giving information about the nation’s history. Each group of people interact differently with their surroundings and cultural influences, emphasizing something westerners often forget: Angola, and Africa itself, is far from a monolith.

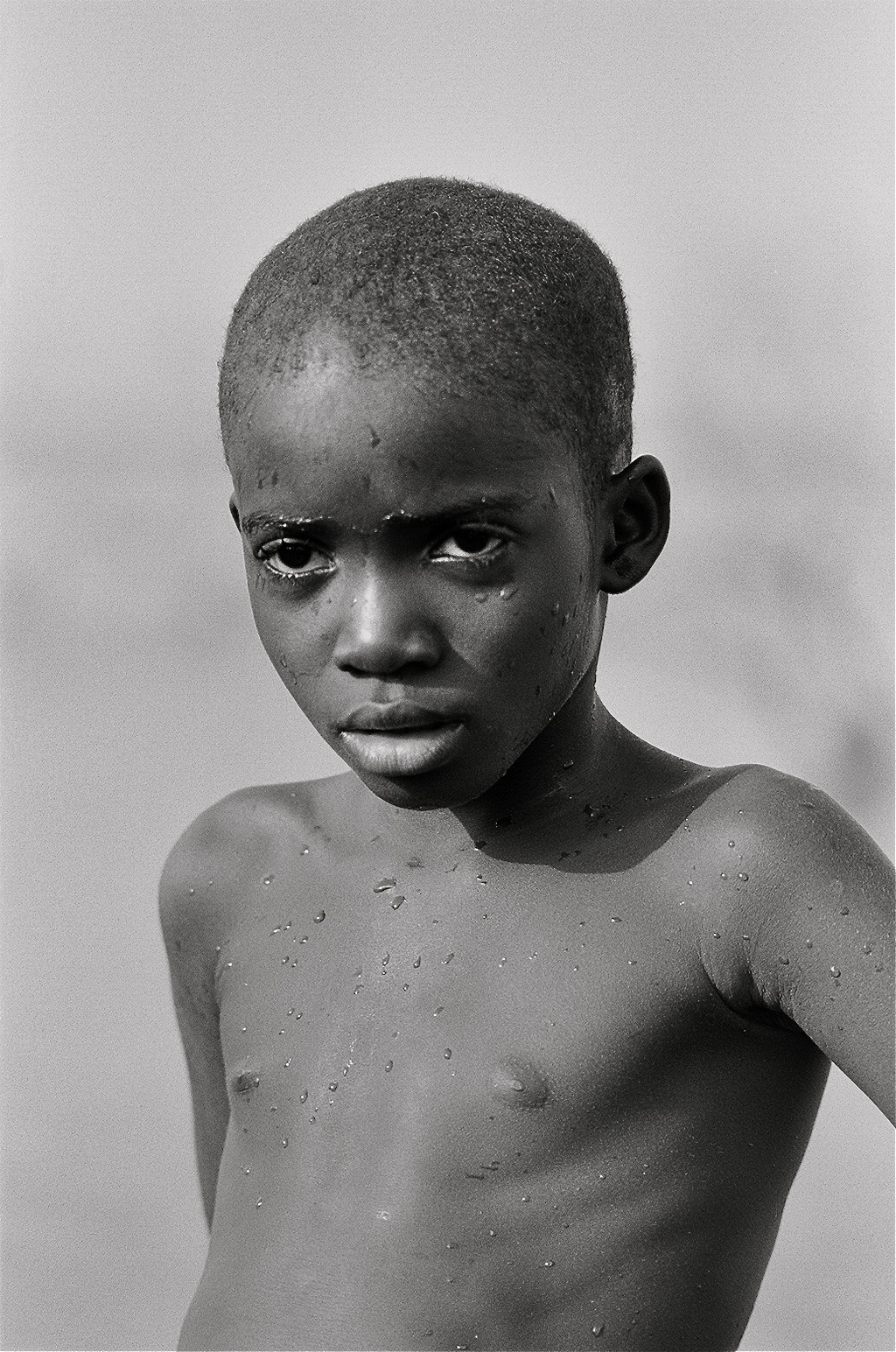

Video: The Amazing Perseverance of Girls in Kibera, East Africa’s Largest Slum

Kibera is a slum in the heart of Nairobi, Kenya, and is rife with poverty, economic inequality, and gender disparities. However, the future is far from dark for young girls living in Kibera, many of whom dream of getting an education and improving their communities. The path out of poverty is incredibly difficult, but as more awareness is being given to communities in need, young people are beginning to receive the resources they need, such as safe housing and free education. This video shows the daily life of Eunice Akoth, a fourth grader at the Kibera School for Girls who aspires to one day become a doctor. Eunice has faced many obstacles throughout her life, especially due to the preferential attention given to the education of boys. However, her fun-loving spirit and determination to succeed have helped her overcome these challenges, inspiring hope not just in her, but in the community she calls home.

Zimbabwean Teens Kick Away Child Marriage with Taekwondo

One town in Zimbabwe has learned to bear the weight of history by “kicking” child marriage customs away.

Zimbabwean woman. ScotchBroom. CC BY-NC 2.0.

In the small settlement of Epworth southeast of Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital, is a growing community of taekwondo enthusiasts. One member, 17-year-old Natsiraishe Maritsa, has taken it upon herself to organize taekwondo classes for the girls of her community. The participants of her classes are underage girls, some as young as 10, who have been subjected to the harrowing practice of child marriage that plagues Zimbabwe.

The Statistics

Child marriage is a tradition practiced all around Zimbabwe, but it runs particularly rampant in rural areas. The Zimbabwean countryside was found to have a child marriage rate of about 40% compared to the urban areas that show a rate of 19%.

In Zimbabwe, 34% of girls are married off before the age of 18, while another 5% are married before the age of 15. The issue of child marriage, although an occurence involving mostly underage women, affects more than just women. About 2% of boys are forced into the practice before the age of 18.

Complications of Elimination

The task of eliminating child marriage has proven to be especially difficult due to the many conditions and societal beliefs that worsen girls’ ability to escape the practice. There are four main reasons that girls are easily trapped in the tradition:

First, gender inequality ranks women as inferior to men, thereby allowing the men of the family to force the women into submission.

Second, and a particularly large piece of the problem, is poverty. The practice of child marriage is often used as an economic tool; the price for a bride is used to cover household expenses. Because marrying off daughters of the family can be the decision between life and death, the pressure to commit these practices is often insurmountable. With poverty increasing due to COVID-19, this problem has become particularly difficult.

Third, the need to avoid shame causes many families to marry off their daughters. In Zimbabwe, the act of a daughter committing premarital sex is seen as shameful to the family, so it is resolved by forcing the daughter to marry her boyfriend. The girls will submit to these demands, especially if they became pregnant, in order to avoid abuse by their family members.

Fourth, a lack of education pushes girls into the trap of child marriage. Many poorer households are unable to pay for their daughters to attend school, which increases the risk that they will be forced into a marriage.

It is an oppressive cycle. Studies find that poverty causes child marriage, and in return, child marriage feeds into poverty.

Seventeen-year-old Maritsa has chosen to use taekwondo education to empower the girls of her community, hoping they can use their newfound confidence and skills to reshape their futures. She holds classes in a small dirt yard in front of her house, while her parents use their small income to supply some food for the attendees.

Maritsa’s class has proven to be empowering, with each class used as a safe space for girls to talk about the physical, mental and emotional abuse they endure from their husbands.

She has proven that although oppressive practices are formidable opponents, the power of education and community can undo even the most controlling traditions.

To Get Involved

Nonprofit organization FORWARD is led by African women seeking to end violence and the oppression of women in Africa, including child marriage. To read more about how to lend a hand, click here.

Global partnership Girls Not Brides has combined the efforts of over 300 organizations dedicated to empowering women on nearly every continent. To see how you can support bills and other legislation they are pushing, click here.

Ella Nguyen

Ella is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Hispanic Studies. She wants to assist in the field of immigration law and hopes to utilize Spanish in her future projects. In her free time she enjoys cooking, writing poetry, and learning about cosmetics.