As Kenya protests proposed Finance Bills, police respond with violent force, threatening freedom of speech.

Read MoreKenya Protests: The Cost of Dissent

The roots of Kenya’s political crisis are echoed as protests shake the nation.

Read MoreHow IVF Could Get Rhinos Off the Endangered Animal List

Before Sudan died in 2018, scientists collected his sperm in hopes of developing an embryo that would carry on the species. In December 2019, eggs from Najin and Fatu were harvested and sent to the same lab as Sudan’s sperm. It is here that scientists toyed with the idea of in vitro fertilization (IVF) for rhinos.

Read More

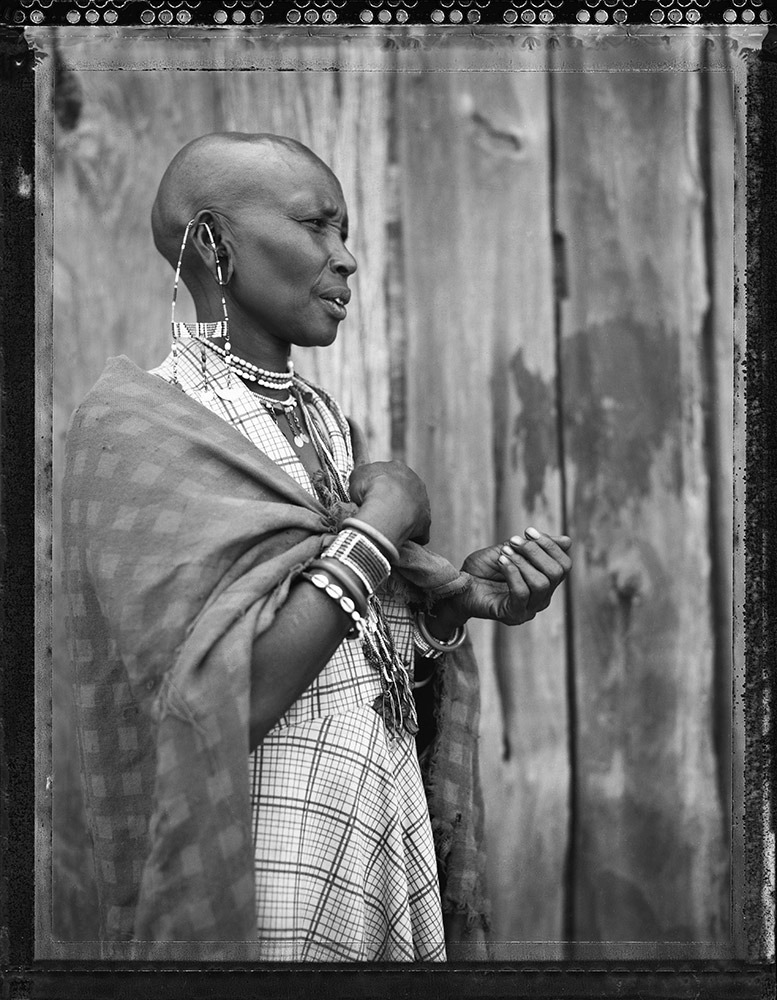

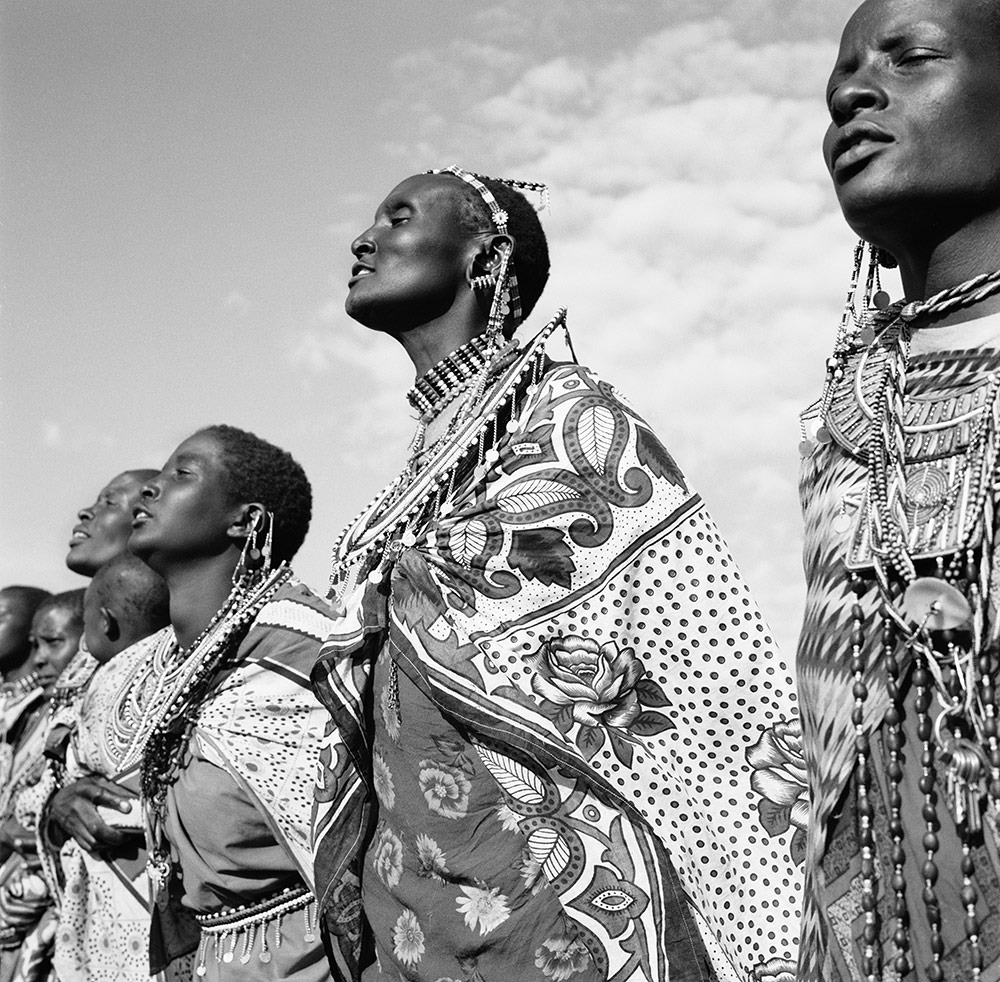

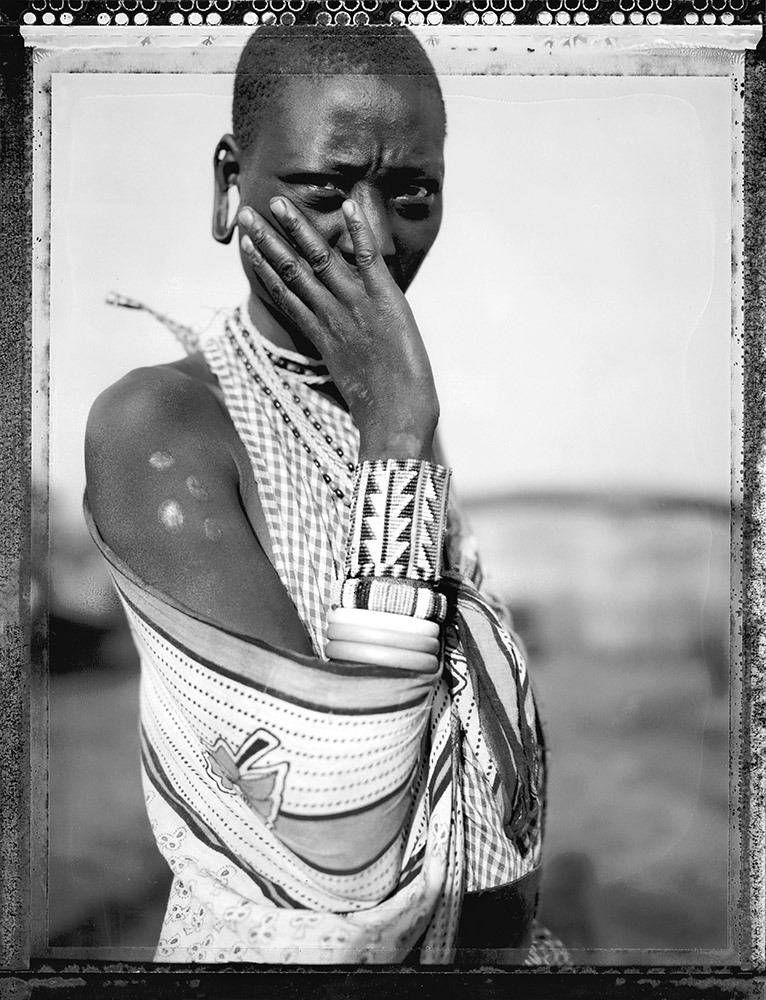

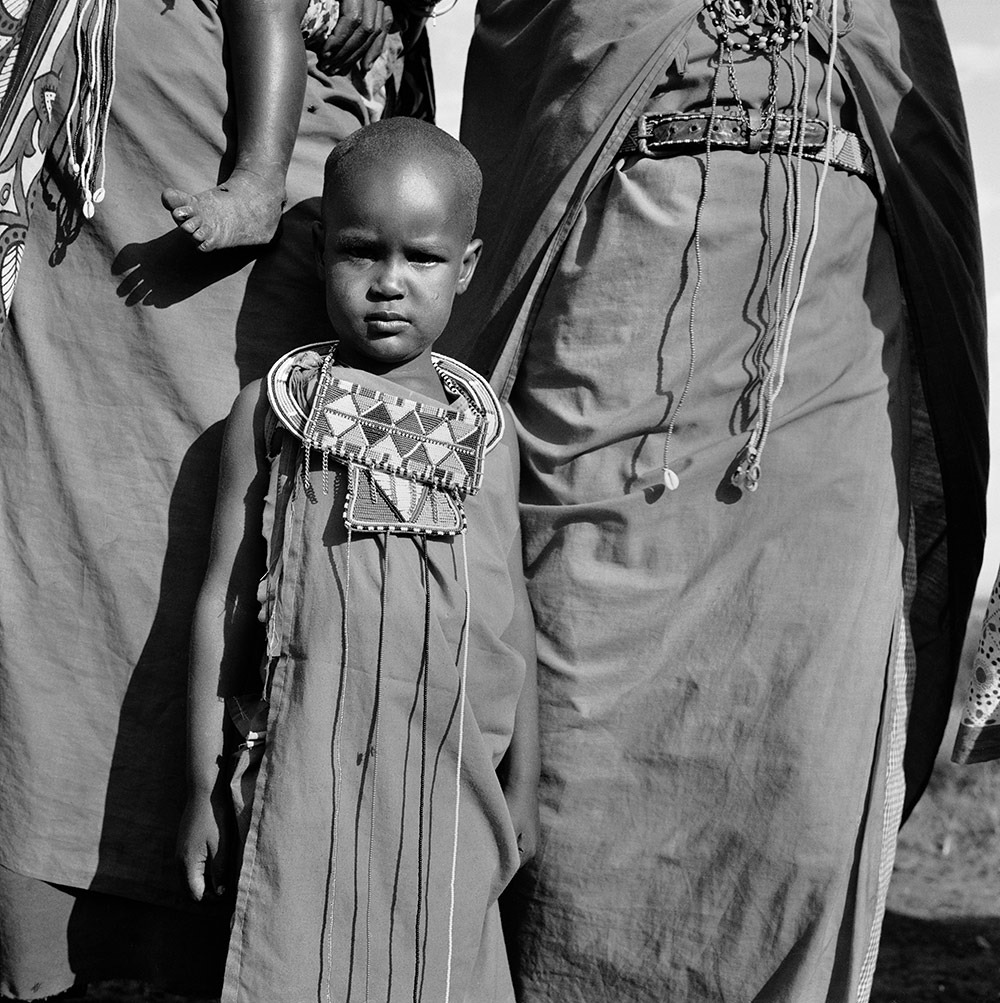

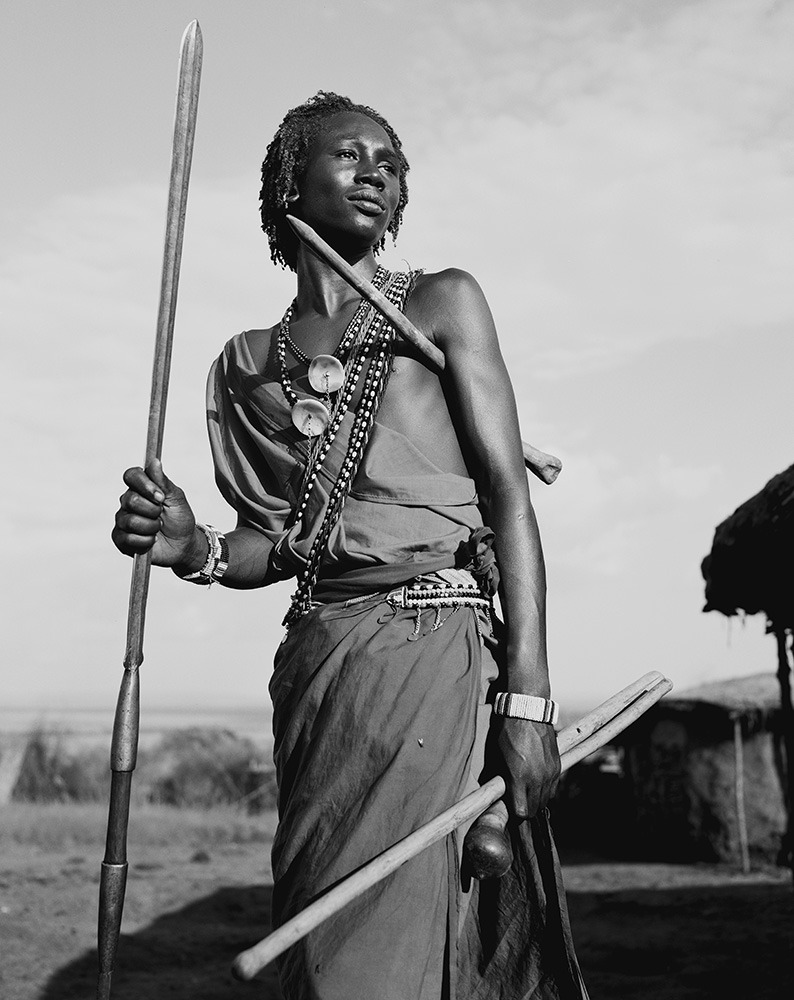

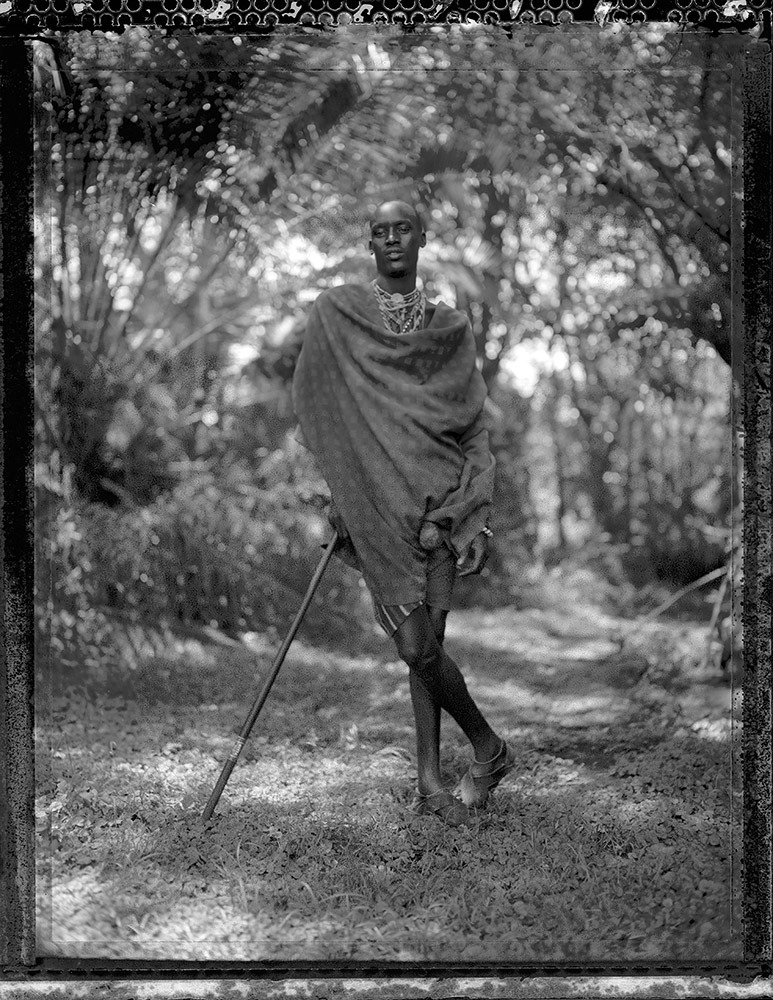

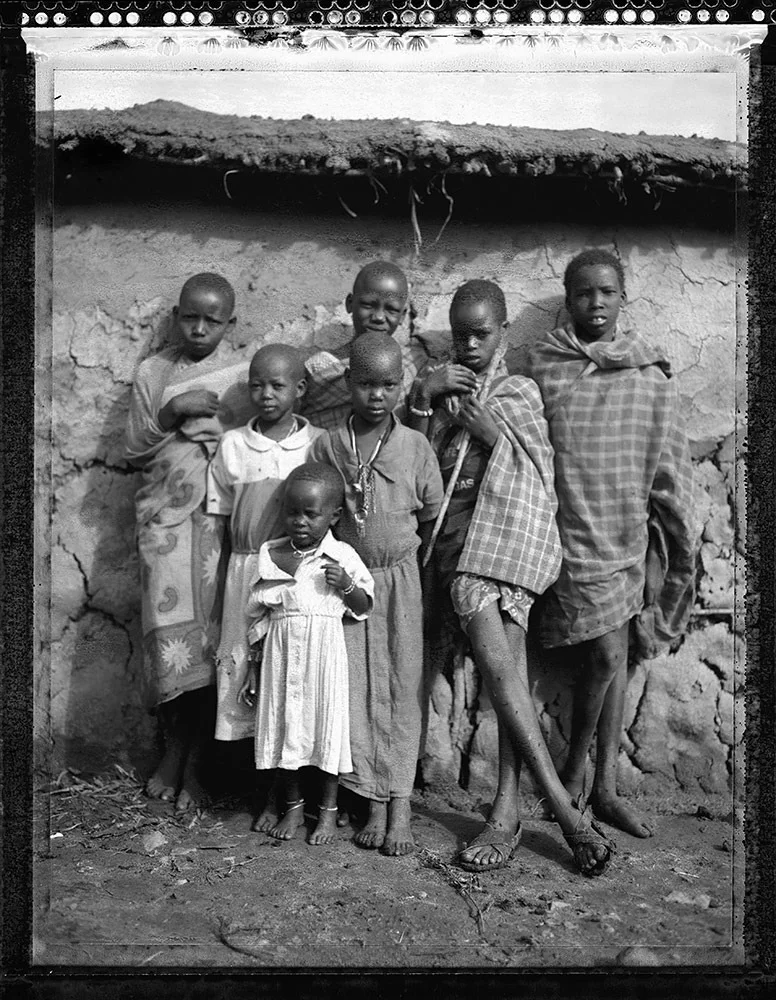

Photo Essay: The Maasai Spirit

This series of images was taken while on assignment in the Maasai Mara Game Reserve in Kenya. As we were leaving the reserve one day our driver suggested we stop at a nearby Maasai village. I thought it would be just a quick stop and a chance to pickup some handmade souvenirs.

Knowing that the Maasai depend on tourists to supplement their subsistence farming, I didn't expect the warmth of our welcome and the genuine dialogue I would have with the chief. He introduced us to the village, showing every aspect of their daily life. Speaking passionately about the realities confronting the Maasai people and the hard choices they must make in order to preserve their cultural identity - from environmental issues threatening their homes and grazing lands, exposure to tourists and the lure of modern life.

He was an erudite speaker, having mastered English and more than 6 African languages. This worldliness empowered him to make mindful decisions governing the collective future of his tribe. All the while recognizing the hypocrisies of a first world existence. In his village no one went hungry, loneliness and depression did not exist and the elders were a revered and integral part of the social dynamic.

He encouraged me to take photos, wanting to share their simple but dignified life, beautiful aesthetic and overt happiness. I hope these images honor the chief's wishes and convey some of the Maasai spirit.

PHOTO + TEXT: JULIEN CAPMEIL

Julien Capmeil is an Australian born photographer living in New York. His work has appeared in many publications worldwide including Vogue, GQ and Conde Nast Traveler.

You can view more of his work online at: www.juliencapmeil.com

For print purchases Email: info@juliencapmeil.com

PHOTO ESSAY CURATED BY NELIDA MORTENSEN

7 Reasons Why Kenya Should Be On Your Ecotourism Travel List

As eco-consciousness grows among travelers, Kenya welcomes them as a beacon of sustainability and natural wonder.

Read MoreVIDEO: Growing Up in a Megaslum in Kenya

Joseph Djemba grew up in Kibera, Kenya, the largest urban slum in Africa. Djemba found himself there when his mother became unable to support her eleven children after the death of her husband. Djemba describes his childhood sleeping outside and begging for food, detailing the psychological impacts of living in poverty. He also notes the large gap between the rich and the poor in Kenya and discusses how impoverished people help each other survive. Djemba is the main character in “Megaslumming,” a book by Adam Parsons. In his work, Parsons explores how the settlement of Kibera came into existence and documents what life is like for those who live in slums.

Get Involved:

Touch Kibera Foundation is a non-profit organization devoted to uplifting children who live in Kibera, Kenya through sports programs, sexual health programs, education support and mentorship opportunities. Donations are accepted online, and more information can be found here.

Polycom Development Project is a foundation which seeks to provide educational and athletic opportunities to girls and women in Kibera. The organization is also devoted to promoting sanitation and public health. Donations are accepted online, and more information can be found here.

St. Vincent de Paul Community Development Organization aims to provide support to orphaned and other vulnerable children in Kibera. The organization supports families and seeks to intervene on behalf of children at an early stage in their development. Donations are accepted online, and more information can be found here.

The Maasai Spirit

This series of images was taken while on assignment in the Maasai Mara Game Reserve in Kenya.

As we were leaving the reserve one day our driver suggested we stop at a nearby Maasai village. I thought it would be just a quick stop and a chance to pickup some handmade souvenirs.

Knowing that the Maasai depend on tourists to supplement their subsistence farming, I didn't expect the warmth of our welcome and the genuine dialogue I would have with the chief. He introduced us to the village, showing every aspect of their daily life. Speaking passionately about the realities confronting the Maasai people and the hard choices they must make in order to preserve their cultural identity — from environmental issues threatening their homes and grazing lands, exposure to tourists and the lure of modern life.

He was an erudite speaker, having mastered English and more than 6 African languages. This worldliness empowered him to make mindful decisions governing the collective future of his tribe. All the while recognizing the hypocrisies of a developed worlds existence. In his village no one went hungry, loneliness and depression did not exist and the elders were a revered and integral part of the social dynamic.

He encouraged me to take photos, wanting to share their simple but dignified life, beautiful aesthetic and overt happiness. I hope these images honor the chief's wishes and convey some of the Maasai spirit.

RELATED CONTENT:

Julien Campeil

Julien is an Australian born photographer living in New York. His work has appeared in many publications worldwide including Vogue, GQ and Conde Nast Traveler.

You can view more of his work online at: www.juliencapmeil.com

For print purchases Email: info@juliencapmeil.com

Where to Travel in 2022

Check out these 20 destinations to consider for your 2022 travel plans. From the Rainbow Mountains of Peru to the Northern Lights of Norway, you will find adventure and more visiting these CATALYST picks.

Read MoreThe Women of Kenya’s Lake Victoria Reject “Fish for Sex”

In a small fishing village on the shores of Lake Victoria, women are breaking the gender roles that dominate the area. A cooperative called No Sex For Fish brings women together to source fish for themselves, without trading their bodies.

A woman carrying a bucket by her boat in Lake Victoria. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“No Sex For Fish” is a bold name. It summarizes what the women of Nyamare have fought for. In the villages along Lake Victoria in Kenya, the fishing industry is split by gender: men do the fishing, women do the selling. Due to overfishing and environmental issues, the lake’s fish population ran low in the 1970s and the fisherman couldn’t catch enough product to supply all of the women.

In a practice the locals refer to as “jaboya,” the men offered the women a trade-off: sex for fish. The women were left without a choice. For many, their families depend on the money they earn from selling fish. To sustain their loved ones and send their children to school, the women complied. After almost 40 years of this routine, the “jaboya” practice went from exploitative to dangerous. Studies have estimated the prevalence of HIV fishing communities around Lake Victoria to be between 21 and 30 percent.

Due to the lack of economic opportunities in the area, the women of Nyamare found themselves in a situation familiar to women across the globe: a position of powerlessness in a system controlled by men. Then in 2011, a woman named Justine Adhiambo Obura led the No Sex For Fish cooperative. The women obtained 30 boats through grants from PEPFAR, USAID and the World Connect charity.

In a testimonial to the World Connect Charity, Justine said, “We are very thankful for this program; it has allowed us to become businesswomen and to control our own finances. The men have to ask us for the money. Though the business has many challenges, we keep working.” With access to their own boats, the women hired men to fish for them. Alice Akinyi Amonde told NPR she’d earn about 50 dollars a day when things were going well, but now she’s lucky if she makes 3 dollars.

In March 2020, after months of heavy rain, the water levels in Lake Victoria climbed to the highest degree in decades. The floods swamped farmland, engulfed homes and displaced thousands of people. Unfortunately, this timing coincided with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and economic activity was put at a standstill. With no homes, no boats and no farmland, the community has been left in limbo.

The organized fishing trade that once supported the families along Lake Victoria’s shore has collapsed. In interviews with NPR in September 2020, the women from No Sex For Fish said that they worry that, even if fishing were to become possible again, the practice of trading sex would re-emerge due to the difficulty imposed by the weed-clogged lake. They also said that, while they want to go back to the trade, they’ll need financial support.

Ruth Odinga, the Kisumu County director of special programs, told NPR that “when such tragedies occur, the government only assists to save lives and not to make life comfortable for them.” With minimal assistance from the government, these women are looking for other ways to earn a living. Despite the challenges they’ve faced, the women of Nyamare are still hopeful for the future.

Claire Redden

Claire is a freelance journalist from Chicago, where she received her Bachelor’s of Communications from the University of Illinois. While living and studying in Paris, Claire wrote for the magazine, Toute La Culture. As a freelancer she contributes to travel guides for the up and coming brand, Thalby. She plans to take her skills to London, where she’ll pursue her Master’s of Arts and Lifestyle Journalism at the University of Arts, London College of Communication.

VIDEO: The Sounds of Kenya

Kenya, located in East Africa, is home to a diverse collection of tribes, cultures, and religions that all intermingle to create the country that over 52 million people call home. While it has undergone development in the late 20th and 21st century, it still has vast swathes of untouched land that is as varied as the people that live on it. This video gives viewers a glimpse of the many different people, places, and landmarks in Kenya, with a focus on the daily joy that residents experience and share with those close to them. While the Kenyans appearing in the video may be from different tribes, they all share the same appreciation for their community and the land that surrounds them.

Amazing Styles of African Architecture

Africa is home to many beautiful styles of architecture, each shaped by the region and time when it developed.

The Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali. UN Mission in Mali. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

While most people are familiar with European styles of architecture, such as Gothic and Renaissance, African architecture is not as frequently showcased. Other than the Pyramids at Giza, Africa’s architectural marvels are relatively little-known. International media often overlooks the cultural, historical and societal diversity of Africa in favor of news that portrays the continent in a negative light. There are a wide variety of architectural styles across Africa, each influenced by their environment and the time when they developed. Below are just three examples of Africa’s many unique architectural styles: Sudano-Sahelian, Afro-Modernist and Swahili.

The Larabanga Mosque in Larabanga, Ghana, built in the Sudano-Sahelian style. Carsten ten Brink. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

1. Sudano-Sahelian

Sudano-Sahelian architecture is characterized by the use of adobe, mud bricks and wooden-log support beams that jut out of the walls, as well as grassy materials like thatch and reeds which are used for roofing, reinforcement and insulation. The name Sudano-Sahelian refers to the indigenous peoples of the Sahel region in Africa—which extends from modern-day Senegal on the West Coast to Eritrea on the East Coast—and the Sudanian Savanna, just south of the Sahel. The Sudano-Sahel region is semi-arid, with an environment that transitions from the Saraha in the north to tropical deciduous forests in the south; there are both trees and wide, grassy plateaus. The earth is a major building resource in the region, which led to the development of the area’s distinct adobe architecture around 250 B.C. Today, ancient Sudano-Sahelian architecture remains a major influence on many contemporary African architects, such as Francis Kéré, who wants to showcase African traditions in his architectural projects.

The courtyard of The Great Mosque at Djenné. Johannes Zielcke. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

One of the most impressive examples of Sudano-Sahelian architecture is The Great Mosque of Djenné in Djenné, Mali. While the mosque was constructed in 1907, there have been a number of mosques on this same site since the 13th century, all built in the traditional Sudano-Sahelian style.

Ghana’s Independence Square. CC Chapman. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

2. Afro-Modernism

Afro-Modernism refers to Africa’s post-colonial experimental architecture boom of the 1960s and 1970s. Thirty-two African nations declared their independence from European colonial powers between 1957 and 1966. New elected governments ushered in an era of public works projects, including university campuses, banks, hotels and even ceremonial spaces like Ghana’s Independence Square. The architecture of the era largely used concrete, as it was more easily cooled than other materials—a necessity in hot, equatorial climates. Afro-Modernism draws on European styles of architecture; many buildings were designed by European architects. African influence is clearly present as well, though, and African architects like Samuel Opare Larbi were crucial to the movement. Staples of Afro-Modernism include bold shapes and the combination of traditional building materials like adobe with modern materials, such as concrete and steel.

Some examples of Afro-Modernism include the Kenyatta International Conference Centre in Nairobi, Kenya which has a lily-shaped auditorium; the FIDAK exhibition center in Dakar, Senegal, which is made up of a number of triangular prisms; and some buildings at the University of Zambia in Lusaka, Zambia, which has various open-air galleries and exposed staircases.

Lamu Old Town in Lamu, Kenya. These stone buildings are made in the Swahili style of architecture. Erik (HASH) Hersman. CC BY 2.0

3. Swahili

Monumental stone structures dating back to at least the 13th century populate the Swahili Coast, an 1,800-mile stretch along the Indian Ocean in modern-day Tanzania and Kenya. The area is rich with coral limestone, which became a crucial building material for the indigenous Swahili people.

A close-up of Swahili woodwork. Konstantinos Dafalias. CC BY 2.0

The stone architecture evolved over time to include intricate decorative elements, such as carved door frames and windows with natural and geometric designs. The carvings in Swahili architecture date back to the 17th century, with the earliest known example being from 1694. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the practice of stone and wood carving grew more widespread. Carvers drew influence from architecture and art overseas, including neo-Gothic, British Raj and Indian Gujarati styles.

A carved stone door in Lamu, Kenya. Justin Clements. CC BY 2.0

A tower in Stone Town on Unguja Island in the Tanzanian archipelago of Zanzibar. Frans Peeters. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Kenya’s Lamu Old Town is the oldest and most well-preserved Swahili settlement on the Swahili Coast. Lamu Old Town is constructed from coral limestone and mangrove timber and has been continuously inhabited for over 700 years. The Stone Town of Zanzibar, on Unguja Island, is another excellent example of Swahili architecture, especially the blending of African, Arabian, Indian and European influences. Both of these towns have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Sudano-Sahelian, Afro-Modernist and Swahili architecture are only three of Africa’s wide variety of architectural styles. Others include Somali, Afro-Federal, Nigerian and Ethiopian. For more stunning pictures of African architecture, visit this Twitter thread.

Rachel Lynch

Rachel is a student at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY currently taking a semester off. She plans to study Writing and Child Development. Rachel loves to travel and is inspired by the places she’s been and everywhere she wants to go. She hopes to educate people on social justice issues and the history and culture of travel destinations through her writing.

Video: The Amazing Perseverance of Girls in Kibera, East Africa’s Largest Slum

Kibera is a slum in the heart of Nairobi, Kenya, and is rife with poverty, economic inequality, and gender disparities. However, the future is far from dark for young girls living in Kibera, many of whom dream of getting an education and improving their communities. The path out of poverty is incredibly difficult, but as more awareness is being given to communities in need, young people are beginning to receive the resources they need, such as safe housing and free education. This video shows the daily life of Eunice Akoth, a fourth grader at the Kibera School for Girls who aspires to one day become a doctor. Eunice has faced many obstacles throughout her life, especially due to the preferential attention given to the education of boys. However, her fun-loving spirit and determination to succeed have helped her overcome these challenges, inspiring hope not just in her, but in the community she calls home.

Five men in Nairobi. Ninara. CC BY 2.0.

Kenya Struggles to Care for the Mentally Ill

While 1 in 4 Kenyans suffer some form of mental illness during their lives, the entire country has but 1 mental hospital of 1500 patients, only 88 psychiatrists and 427 psychiatric nurses and 10 social workers. But help from the government will be soon coming.

Read MoreCOVID-19 Further Complicates Kenya’s Health Care System

Kenya is facing a double burden of communicable and noncommunicable diseases. Clustering of infections, such as HIV and tuberculosis, and noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, renders Kenyans vulnerable to COVID-19. This has pressured an already overstretched health care system.

Hospital entrance sign in Kenya’s Rift Valley province. Melanie K Reed. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In mid-March, shortly after Kenya’s first confirmed COVID-19 case, the word “corona” began circulating around western Kenya’s villages. Young people used the word as a novelty, and the overall population remained preoccupied with existing illnesses. “This is a disease for whites,” said Sylvanus, a local father of seven. When calling after white people on the street, children replaced their traditional “mzungu!” (white person) with “coronavirus!” At this point, Europe was the pandemic’s epicenter. Kenyans felt that this foreign virus was removed from their world.

However, Kenya’s high prevalence of preexisting health conditions renders a significant portion of the population immunocompromised and therefore vulnerable to the coronavirus. In a country experiencing health issues such as HIV, tuberculosis, diabetes and malaria, the pandemic has posed a threat to an already fragmented health care system. Although less than 4% of Africa’s population is over the age of 65, countries such as Kenya have seen high coronavirus mortality rates.

Global evidence shows that people with underlying medical conditions are at a greater risk from COVID-19. In 2019, half a million Kenyans were living with diabetes, and over half of accounted deaths were associated with noncommunicable diseases. Currently, Kenya’s health care system is structured to manage individual diseases, rather than multiple ones. Because patients frequently carry more than one health condition, the health care system has been overstretched and inadequate. HIV, tuberculosis and malaria treatments are easily accessible, but noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes and cancer often go undiagnosed, and care is costly. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these shortcomings, as social distancing restrictions prevent Kenyans from accessing medical resources, and a surge of coronavirus cases imposes a double burden of disease. Additionally, front-line workers with undiagnosed, chronic illnesses have critically compromised their health, and hospitals have dealt with equipment shortages.

Transcontinental travel has heavily contributed to the increase in COVID-19 cases across Africa. In order to minimize Kenya’s number of infections, President Uhuru Kenyatta stopped all flights from Europe. Kenyatta also imposed a national curfew and restricted movement between populated areas. Domestically, middle-class, urban dwellers have carried the virus into rural areas. On Kenyan television, villagers have urged educated, urban residents to remain in the city, instead of threatening the lives of others.

In African countries, lockdowns are nearly impossible to implement because they would spur social and economic crises. Many people rely on cash earned daily to sustain themselves and their families. A strict lockdown would result in poverty and starvation. Kinship systems also play a crucial role in social welfare, as relatives care for one another. For people already barely getting by, cutting these social ties would be dangerous. Finally, a lockdown would interrupt the supply chains of essential drugs, preventing access to tuberculosis, HIV and malaria treatments.

According to several African presidents, developed countries are failing to fulfill their pledges of financial support and debt relief. Throughout the pandemic, outside aid has not met the continent’s needs. While wealthy countries in the global north have funneled trillions of dollars into their own stimulus packages and health initiatives, the global south cannot afford such measures. With limited testing capacity, Africa has not confirmed many of the world’s COVID-19 cases, but the continent has been grossly affected by the economic crisis and global trade disruptions. Furthermore, the global shortage of testing kits, hygienic material and personal protective equipment has left developed countries vying for their own supplies, without consideration for underdeveloped nations.

Anna Wood

is an Anthropology major and Global Health/Spanish double minor at Middlebury College. As an anthropology major with a focus in public health, she studies the intersection of health and sociocultural elements. She is also passionate about food systems and endurance sports.

Nairobi’s current waste disposal system is fraught with major problems. EPA/Dai Kurokawa

How Nairobi Can Fix Its Serious Waste Problem

Uncollected solid waste is one of Nairobi’s most visible environmental problems. Many parts of the city, especially the low and middle-income areas, don’t even have waste collection systems in place. In high income areas, private waste collection companies are booming. Residents pay handsomely without really knowing where the waste will end up.

The Nairobi county government has acknowledged that with 2,475 tons of waste being produced each day, it can’t manage. Addis Ababa Ethiopia has a similar size population but only generates 1,680 tons per day.

Nairobi’s current waste disposal system is fraught with major problems. These range from the city’s failure to prioritise solid waste management to inadequate infrastructure and the fact that multiple actors are involved whose activities aren’t controlled. There are over 150 private sector waste operators independently involved in various aspects of waste management. To top it all there’s no enforcement of laws and regulations.

Nairobi’s waste disposal problems go back a long way and there have been previous efforts to sort them out. For example in the early 1990s, private and civil society actors got involved, signing contractual arrangements with waste generators. They often did this without informing or partnering with the city authorities.

More recently other strategies were put in place, some of which left parts of the city clean. They worked for a period, but unfortunately they weren’t sustainable because no institutional changes were made.

But there’s hope on the horizon with a new Nairobi Governor – Mike Sonko Mbuvi. He should learn from the mistakes of the past and put a new regime in place that addresses the structural problems that have plagued the city. This would include an improved improved collection and transportation plan that incorporates the private sector.

Learning from the past

In 2005 John Gakuo took over the management of city affairs as the Town Clerk. During his tenure (2005-2009) he made a deliberate effort to introduce new approaches.

When he took over the city only had 13 refuse trucks. They were able to collect a paltry 20% of the waste produced by the city. To overcome this, the authorities contracted private waste collection firms to collect, transport and dispose waste at Dandora dump site which is the biggest and the only designated site. This quickly boosted the total waste collected with levels oscillating between 45%-60%.

Other changes included:

The development of a proper waste collection and transportation schedule with market operators. This meant waste from open-air markets was brought to identified collection points on specific days.

A weighbridge to measure amounts of waste disposed at Dandora was introduced. An important way to know disposal levels vis-a-vis collection and generation.

Enforcement officers were deployed to prevent dumping in parts of the city that were notorious for waste accumulation.

Over 2,000 arrests were made, making residents aware that indiscriminate dumping was illegal and punishable under the city authority laws.

All these efforts paid off – for parts of the city. For example, the heart of the city, the Central Business District, was cleaned up and waste was brought under control.

But crucial elements that would have ensured that the changes were sustainable were left out. For example, no new physical infrastructure, like the construction of waste transfer centres and proper landfills, were built, nor was new equipment bought.

After Gakuo’s regime, the next one worth a mention is Evans Kidero’s regime (2013 - 2017). It can be credited for trying to fast-track the implementation of the Solid Waste Management Master Plan which assessed the waste management problem of Nairobi and developed projects that could be implemented to ensure a sustainable system was in place.

This ensured that while the private sector needed to help with waste collection and transportation, the government was key to institutionalising waste management services.

Thirty waste collection trucks were bought and serious investment was made into heavy equipment. And in an effort to streamline waste collection a franchise system of waste collection was rolled out. This involved dividing the city into nine zones to make it easier to manage waste.

The franchise arrangement gave private operators a monopoly over both waste and fee collections, but relied heavily on the public body for enforcement of the system.

The franchising system failed due to a lack of enforcement by the city. In addition, in-fighting broke out between the private waste collection firms that had individual contracts with waste generators and the appointed contractor.

But other changes introduced during this period were more successful and had longer lasting effect. For example new laws were introduced designed to create order in the sector. These included the solid waste management act in 2015. This classified waste and also created a collection scheme based on the sub-county system. It also put penalties in place.

In addition, in 2016, 17 environment officers were appointed and posted to the sub-counties to plan and supervise waste management operations alongside other environmental issues.

These changes planted the seeds of an efficient and working waste management system. But the regime fell down when it come to enforcement. This meant that the gains that had been made were soon lost.

What needs to be done

Expectations are high for the new regime that has taken over. It should look to fast-track the following programmes:

Implement an improved collection and transportation plan that incorporates private sector and civil society groups;

Establish a disposal facility to reduce secondary pollution from the city’s dumps;

Decommission the Dandora dump site;

Implement the re-use, reduction, and recycling of waste;

Establish intermediate treatment facilities to reduce waste and its hazards;

Create an autonomous public corporation;

Put in place legal and institutional reforms to create accountability;

Implement a financial management plan, and

Implement private sector involvement.

Nairobi can fix it’s waste disposal problems. All it needs is focused attention, good governance and the implementation of systems that ensure changes outlive just one administration.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

LEAH OYAKE-OMBIS

Part-time lecturer and Director of the Africa Livelihood Innovations for Sustainable Environment Consulting Group, University of Nairobi

Kenyans Face Up to 4 Years In Prison For Using Plastic Bags

Beginning today, plastic bags will no longer be found in Kenya. If someone is found using one, then they will face a $38,000 fine or potential four-year jail sentence.

It’s officially the world’s harshest plastic bag deterrent.

A full ban on producing, selling, or using plastic bags went into law Monday after a court rejected challenges brought by two large plastic bag importers. The new law was successfully implemented on the third time around, after the first bag-ban in Kenya was proposed over 10 years ago.

Plastic bag pollution is a persistent problem in Kenya. It is not uncommon to see large piles of the single use bags littering the streets of urban centers, where vendors and customers frequently use them to sell and transport items.

Though the bags are convenient, the ultimate cost to the environment is astounding.

"Plastic bags now constitute the biggest challenge to solid waste management in Kenya,” said Kenya's Environment Minister Judy Wakhungu in an interview with the BBC. “This has become our environmental nightmare that we must defeat by all means.”

According to Wakhungu, plastic bags can last anywhere from 20 to 1,000 years in a landfill before they biodegrade. In the meantime, they pose environmental hazards to the communities they end up in.

Serious concerns were raised about the safety of bag disposal when rements of plastic bags were found in the stomach of cows who were to be slaughtered for human consumption. Leaching of plastics into beef destined for supermarkets pose a worrying health risk, according to local veterinarian Mbuthi Kinyanjui.

“This is something we didn’t get 10 years ago but now it’s almost on a daily basis,” he told the Guardian.

Scientists are concerned that the pile up of plastic bags is having a similar negative effect on the marine food chain, where plastic particles can easily make their way into the fish humans eat. The bags also threaten sea life not consumed by humans, such as dolphins, whales, and turtles.

In a country that uses an estimated 24 million plastic bags per month, many see the move as a victory for the environment.

However, some people in the business community worry that the ban will ultimately harm economic prosperity, and generally make life more difficult for the average Kenyan.

Kenya is a major exporter of plastic bags in Africa.

In an interview with the Guardian, spokesman for the Kenyan Association of Manufacturers Samuel Matonda said the ban would eliminate 60,000 jobs and cause 176 manufacturers to close.

“The knock-on effects will be very severe,” Matonda said. “It will even affect the women who sell vegetables in the market – how will their customers carry their shopping home?”

Right now, Kenyans discovered using bags will only have them confiscated with a warning. Soon, they could face the penalties of what is being called the “world’s toughest law against plastic bags.”

Several other African nations have already enacted similar bans or fines on plastic bag use, as have more than 40 countries around the world including China, France, and Italy.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GLOBAL CITIZEN.

ANDREW MCMASTER

Andrew McMaster is an editorial intern at Global Citizen. He believes that every voice is significant, and through thoughtful listening we can hear how every person is interrelated. Outside of the office he enjoys cooking, writing, and backpacking.

Visions of Kenya

A long time went by before I was able to understand this trip. Sometimes, the present is not understood until it becomes the past. Kenya belongs to a continent of origins, remote and distant, and for now, for better or worse, many of its vast and beautiful rural areas remain far from the globalised world.

In a matter of two weeks I had organised everything. Bought the tickets from Buenos Aires to Mombasa, got the necessary vaccines, packed my things and let my friends know I was leaving. “I’m going to Kenya for a month, alone, just my backpack and camera, nothing else.” It was a long flight to Mombasa. I was very tired and somewhat nervous about it all. At the airport in Mombasa the image of a rhino gave me goosebumps. I had arrived.

— Mombasa —

The first morning I was woken by the heat and the unrelenting racket made by the many crows that inhabit Mombasa. I looked outside the window to see Africa for the first time: bonfire smoke on the sides of the street, women selling fresh fruit right outside our building, next to them, I saw other women with beautiful braids in their hair, and a little further away, a man selling plants. Here, life takes place on the streets.

He was selling onions on the side of the road to Nairobi

I enjoy travelling alone and getting to know different cultures, in the most simple and genuine way possible, simply by being there, and merely observing. Trying not to alter what I see, to be inconspicuous. But in Mombasa, I was noticed right away. I am a white Argentinian, in a city where almost everyone is black. It was impossible to remain unseen.

Sunday morning is a social time for families at the public beach

The first few days were filled with nervousness and anxiety. I was alone in a place completely different to my own, full of tension and expectations about what the trip might become. Was I going to be able to adapt to Africa? I just wanted to let go, come to know the locals, let down my resistance, and give myself up to whatever had to happen.

Eddie lives inside a garbage container in Mombasa. The day I left Kenya, I gave Eddie all of my clothes.

Two days went by and I decided it was time to get out of the city. Venturing into the more rural areas of Kenya would be better than staying in Mombasa. Leaving my big backpack behind, I grabbed my camera, my flip flops, swimming trunks, and my kikoy — a traditional man’s wraparound worn on the Swahili coast of East Africa, especially in Kenya. It protected me from the sun and from the stares too. I took a tuk-tuk to the south of town, then a ferry, and then a three-hour matatu — one of Kenya’s colourful buses. My destination was Wasini Island, a small island in the south, where people usually snorkel for a few hours and then leave. I wanted to stay, at least for a few days.

School children on the road from Mombasa to Kilifi / She was sleeping in the matatu along the way.

I was greeted by Abdullah, who was surprised to meet a foreigner who wanted to stay longer than a few hours. I got on a small boat and crossed the island with two guys who were carrying huge machine guns, which they used to absentmindedly scratch their feet and faces — I had never seen such big weapons.

Baobab tree lit up at night

— Wasini —

Wasini is a coral rock island that during its hey-day was a popular summer destination for retired and wealthy Europeans who wanted to enjoy the heat and beaches of Kenya. The day I arrived, there was just one dutchman and me, and the rest of the island was a small fisherman’s village. Abdullah cooked a fish for me with great care, and later made me visit the “tourist attractions,” which meant very little to me.

Coral stones in the Indian Ocean

I met someone who said he would take me over to the other side of the island along a path that would pass through the mangroves. I told him I had very little to tip him with, as I had left all my money in Mombasa. He gently insisted on taking me and I followed him. We walked through the island for a long time and I started to worry, thinking about where this stranger was actually taking me. The sun had started to set and as is common in many places in Kenya, there was no electric light.

We were crossing the path with this guy, while a fisherman was preparing his bait. I asked to take a picture of him, and he accepted.

We kept on walking until we finally reached the other side of the island. The mangrove trees continued all the way into the sea, and it was a very beautiful sight. I calmly took a breath, my guide had not deceived me. At that moment I felt that if I had managed to get to such a remote place with a complete stranger, then it meant that the rest of my trip would turn out alright. It was a feeling I had. Complete trust.

Among the mangroves

— Kilifi —

I spent a few days in Wasini and then returned to Mombasa to continue northwards along the coast, towards Kilifi. In Kilifi there was a very impressive hostel, but when I entered I had the feeling of being out from what I have been seeing. Luckily, I decided to walk towards the beach, where I found a beautiful sunset.

Little sisters playing together in a tree near their home.

The beach was deserted. It was actually an estuary, very serene. I loved rural Kenya, so far away from the cities. As I sat with my camera I saw a kid walking in the distance. As he approached me I waved, then he waved back and continued to walk. A few hours later, the kid returned and I went over to have a chat. He responded by asking me if I knew how to hunt crabs. His name was Buda.

Portrait of Buda

We became friends and I met all of his brothers and sisters as well. They were many, and lived on the coast with their aunts and cousins. Most families in Kenya live with their extended family, and the women are in charge of the houses. Men are absent most of the time, often spending time with friends, away from their homes.

Full of joy in the ocean / Fishermen and family in the early morning

I quickly became very fond of Buda and his siblings, and they became fond of me. Every time I came down to the beach, they would arrive to greet me. I spent whole days on the beach, sometimes helping them gather wood for making fires, or finding things their mother had asked for — I learnt a lot about their culture and way of life, which was not always easy. Buda and Nuzrah were the eldest siblings and spoke better English. They taught me a lot of words in Swahili, their native tongue.

Portrait of Nuzrah

One of the days we spent together I brought them a football, a water gun and a jumping rope. We played with them, they taught me beach games, and every now and then we would all go for a swim. It was with great grief that I said goodbye to these children, as I had to continue travelling towards the west of the country. They stayed with me until I left, and their mother also came to say goodbye.

Portrait of Buda / Jumping rope / Portrait of Mwanaisha

— Amboselli —

I took a tuk-tuk back to Mombasa, thinking about everything I was experiencing. It felt so powerful and different, making me reflect on my own life, and how grateful I was for the opportunity to travel. The following dayay I left for Amboselli National Park. Enormous and open, there were no fences around it. Animals are not easy to see. You might spend a whole day walking around and only encounter a few zebras.

Morning of the Zebras

But the immensity and beauty of the landscape was truly dazzling to me, sometimes reminding me of my native Patagonia, similarly wild and empty in its own way. I also thought about the devastation humans have caused to the natural environment, and the complex challenges local and international communities face as they attempt to tackle and reverse this.

Afternoon of the elephants

I spent my whole childhood fascinated by documentaries on Animal Planet, or Discovery Channel. I could not quite believe I was there, in these vast landscapes. The animals were so big, so strong. They had very little to do with the image I had of elephants in zoos or television. And the trees, they were so magical, I really have no words to describe them.

Masai walking in the early morning / Just a beautiful tree, in my first moments in the park

A long time went by before I was able to understand this trip. Sometimes, the present is not understood until it becomes the past.

When I travel, I seek to explore places that will surprise and challenge me, and from that surprise create beautiful experiences and photographic visions of what I have witnessed. Kenya belongs to a continent of origins, remote and distant, and for now, for better or worse, many of its vast rural areas remain far from the globalised world.

Early morning at Tsavo. There is always magic in the first hours of the day.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

FRAN PROVEDO

Fran Provedo is a photographer and Architect from Argentina. Passionate about nature, and what is invisible in it.

28 Millimetres Project

Meet French artist and TED Prize winner JR whose public art installations in France, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Brazil, Israel, and Palestine encourage people to see the world in a new way. INSIDE OUT is his participatory art project that transforms messages of personal identity into pieces of artistic work. “Stand up for what you care about” JR says, “and together we’ll turn the world INSIDE OUT.”

TAKE YOUR PICTURE AND SUBMIT IT TO HIM AT INSIDEOUTPROJECT.NET

CHANGE HEROES: The Trip that Changed the Way to Give

Back in 2009, Taylor Conroy took a trip to Kenya and Uganda in pursuit of a vacation and means of getting himself involved. Little did he know that this decision would cause for him to start a movement; Change Heroes -a friend-funding platform which gives anyone the tools they need to raise $10,000 and build a school, library, or water well anywhere in the developing world. In this video, Taylor talks about that initial, innocent trip, which caused his life, and the lives of thousands of others, to change for the better, forever.

CONNECT WITH CHANGE HEROES

VIDEO: Change Heroes and Free The Children Help the World in 3 Hours

Watch what 22-year-old Evan Mula, from Boston, did with just a bit of time. He and 32 of his friends raised $10,000 in three hours to build a school in Kenya through Change Heroes and Free The Children. This is his trip to see that vision emerge in reality. Evan is able to demonstrate that anyone can change the world with just a bit of hard work. He now sets a standard for activists who work in Kenya.