Paige Geiser

A man standing near Najin and Fatu in a grass field. Dianne Magbanua-Negado. CC0.

According to scientists such as Anthony Barnosky, a professor of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley, the world is currently in the midst of its sixth mass extinction. Mass extinctions typically occur over the course of two million years and are characterized by the loss of 75% of Earth’s species. Because of the extensive time frame a mass extinction takes to occur, there are many debates on whether we are currently in a sixth mass extinction or if it still lies ahead. Either way, global wildlife populations have seen a 73% decrease over the last 50 years. This environmental damage is primarily due to human activities that are leading to unprecedented rates of biodiversity decline and species loss. One of the many species currently experiencing this hardship is the northern white rhinoceros. The last two northern white rhinos are living in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Nairobi, Kenya, where they are protected by an armed guard 24 hours a day. Their names are Najin and Fatu.

Najin and Fatu’s battle with extinction isn’t the result of natural selection but rather a consequence of human actions. At the turn of the 19th century, hundreds of northern white rhinos roamed Central Africa. As the black market value for their horns quickly skyrocketed, so did the number of poachers. Buyers in Africa and Asia covet rhino horns for many different reasons. Some believe they have medicinal healing powers, while others turn the horns into extravagant cups and figurines. Driven by demand from high-end buyers, poachers often killed these rhinos solely for their keratin horns, leaving their decaying bodies to rot in the savannah.

To confront this poaching of the local species, Kenya devised a special unit called the Wildlife Service Unit. Formed in 2010, this unit’s full responsibility is to prevent the illegal hunting and capturing of wild animals. They do this by conducting wildlife censuses and removing snare traps placed by poachers. While this unit has had quite the success, it unfortunately was created too late to help the northern white rhino population.

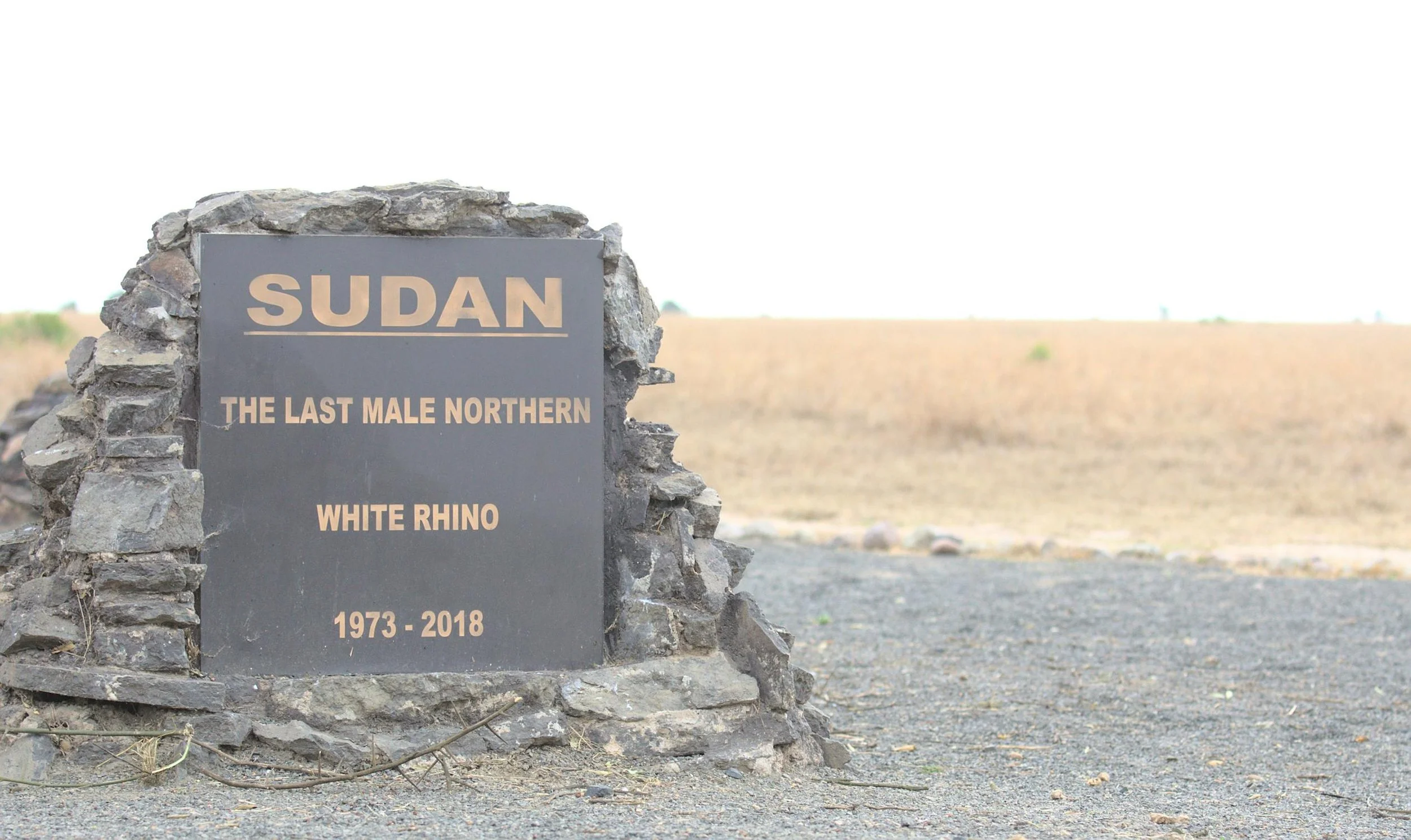

The last male northern white rhino, Sudan, died in 2018. He was taken as a two-year-old calf and placed into the Dvur Kralove Zoo in the Czech Republic. It was in this zoo where he fathered Najin in 1989 and Fatu in 2000.

A tribute to Sudan in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy. Nirav Shah. CC0.

In efforts to encourage more breeding, the three rhinos were transported to the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, where another northern white male named Suni resided. Unfortunately, Suni died before he could mate. After the trio was transported to the conservancy, it was found that neither Najin nor Fatu could give birth. The years Najin spent at the zoo left her with bent legs and a permanently altered posture that destroyed any hope of carrying a pregnancy to term. Fatu was able to dodge this problem because of her fewer years at the zoo, however, veterinarians found that there was an issue with the lining of her uterus. With seemingly no hope of these northern white rhinos successfully creating an offspring, the keepers at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy turned to science for help.

Before Sudan died in 2018, scientists collected his sperm in hopes of developing an embryo that would carry on the species. In December 2019, eggs from Najin and Fatu were harvested and sent to the same lab as Sudan’s sperm. It is here that scientists toyed with the idea of in vitro fertilization (IVF) for rhinos. Keeping the precious northern white rhino eggs in liquid nitrogen, scientists attempted IVF technology on the more prevalent southern white rhinoceroses. Finally, on January 24, 2024, a team at BioRescue successfully impregnated a southern white rhino via IVF.

Unfortunately, the surrogate mother died from an infection caused by Clostridia, a bacterium found in the soil that was released due to heavy rain. She was 70 days into her pregnancy. While the southern white rhinoceros' death was tragic, it showed that IVF is a viable option to save the northern white rhino species. Although it has been over a year since the first successful rhino IVF, scientists have yet to place one of the 33 northern white rhinoceros embryos into a southern white rhino surrogate. Scientists are hoping to create a northern white rhino offspring before Najin and Fatu die so that it can learn the tendencies and social behaviors of the species from its own kind. With the average lifespan of the northern white rhino being 40 years, the biological clock is ticking.

While using Sudan’s sperm from 2018 is a long shot, it could be the very thing that keeps this species from extinction. The technological advancement of IVF for animals gives hope for helping other endangered species. Other rhinos, such as the Sumatran and Javan rhinos, are also critically endangered, each having under 100 rhinos left. If IVF is successful in helping the northern white rhino, these subspecies could be next to receive treatment. Although this new breakthrough could help endangered species, anti-poaching services such as Kenya’s Wildlife Service Unit do more for the animals than IVF ever will.

GET INVOLVED:

To learn more about the effects of poaching or to donate to help support Ol Pejeta Conservancy’s work, click here. Other organizations that help fight against poaching and biodiversity loss are the World Wildlife Fund and Re:wild. Both of these organizations were founded by scientists and conservationists to help protect vulnerable wild animals and their habitats across the globe. They work with governments, like-minded organizations, park rangers and local communities to restore habitats and stop wildlife crime.

Paige Geiser

Paige is currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree in English with a minor in Criminal Justice at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. She grew up in West Bloomfield, MI, and has been fortunate enough to travel all throughout the country. She is an active member of the university’s volleyball team and works as the sports reporter for The Racquet Press, UWL’s campus newspaper. Paige is dedicated to using her writing skills to amplify the voices of underrepresented individuals and aspires to foster connections with people globally.