Billy Barr lives a simple life. He enjoys tea, sitting by the fire and reading. He lives alone in a house he helped build in a remote Rocky Mountain location. But what really gets him going is the weather, and more specifically, the snowfall in his neck of the woods. So he started taking notes about it: every winter, twice a day for 40 years. These detailed snowfall notes have become a treasure trove for scientists studying climate change.

AUSTRALIA: Christmas Island's Red Crab Invasion

Every year in late October, Christmas Island sees red. Lots of red. During the annual crab migration, the island’s endemic red crabs travel from their home on the rainforest floor to the shore to mate and spawn. This mass migration of around 40 million crabs is a spectacular sight to behold.

ECUADOR: The Galapagos

Andrew Norton recently got invited to visit the Galapagos islands in Ecuador. Just before returning home he called his wife, Katie, to tell her about it. A tale of trying quasi-adventurous things, Darwin marrying his cousin and riding a tortoise, and a kid that can do 1000 kick-ups, among other things.

ICELAND: Vindur Means Wind in Icelandic

The word Vindur means ”wind” in Icelandic which is relevant to the way this video was captured. For 3 minutes you will get to enjoy amazing drone footage portraying Iceland’s unbelievable landscapes. From beautiful waterfalls to endless valleys, with its unusual mountain ranges and out of this world landscapes, oceanic cliffs, old glacier, fantastic canyons and many other wonders, take look at what make Iceland so unique.

Digital technology may help improve the effectiveness of anti-stigma education programs. (Shutterstock)

From Recognition to Transformation: How Digital Technology Can Reduce Mental Illness Stigma

When those with mental illness experience prejudice and discrimination in the form of stigma, it can make their suffering considerably worse.

Spreading awareness and understanding through education is one of the strategies used to tackle the problem. Years of public education campaigns have helped open the conversation. Yet evidence suggests that stigma against people with mental illness remains a problem in our health-care system.

Consider what the experience is like for a young person who seeks mental-health care. They may suffer for a long time before they eventually build up the courage to ask for help. When they share this with a family member or a friend, they may be encouraged to look for help, but encounter a long waiting list for treatment. Over time, they continue to struggle and things get worse. If they end up in crisis, they might need to seek emergency care.

People seeking mental health care may face long waits for treatment. (Shutterstock)

The doctor, nurse or mental health professional they encounter is probably struggling within a challenging system. Health-care professionals work hard with limited resources, soaking up the suffering of others until they begin to detach from their own humanity for self-protection. They might appear rushed. They might seem distant. This can result in the patient feeling dismissed or feeling judged.

As a psychiatrist, I bear witness to a broken system. Mental-health care is chronically underfunded. If a parent has one child with diabetes and one with anxiety or depression and they seek help, the child with diabetes receives world-class care. The child with mental illness is given a sheet of paper and a 12- to 18-month wait.

Encountering blame and shame

As a stigma researcher, my team and I found that when individuals seek help for their mental illness in settings like hospitals or emergency departments, they frequently encounter blame and shame. We also found that many health professionals stigmatize without even being aware of it.

We quickly learned that no matter how well-intentioned health professionals may be, they do not always intend to say what their patients and their families hear.

Stigma in health care is automatic. It is embedded within the fabric of the system. Can we really expect training and workshops for health-care workers to solve the problem?

One of the problems with existing stigma reduction education is that it’s delivered through in-class formats that are fairly one-dimensional. Advances in digital and social media may have the potential to challenge traditional approaches to learning and provide real-time delivery of information to a huge audience. For example, medical journals that leverage social media have a much greater impact than those that do not.

Social media can be an effective way to keep health professionals up to date. (Shutterstock)

Hashtag campaigns on social media are another example. Instead of educating people about mental illness in a classroom, a viral social media post can inspire a social movement. Digital tools like social media, blogs and wikis provide knowledge for health professionals who can use this technology to learn about a topic while deepening their engagement and promoting collaboration.

Research shows that social media is an effective and efficient way to keep health professionals up to date with the latest knowledge to improve the quality of health care for their patients.

Sharing stigma-reduction tools

Digital technology also makes stigma-reduction education freely available to everyone. By putting knowledge about stigma in the hands of patients and caregivers, technology democratizes expertise.

An example of the power of digital technology to improve health care can be found in pediatric pain research. Led by clinical psychologist, Dr. Christine Chambers, #itdoesnthavetohurt is a science-media partnership that brings evidence-based information about children’s pain directly to parents.

Chambers found that numerous eHealth tools for pain assessment and management are developed, yet have a reduced impact because they are rarely made available to patients and families. She and her team targeted their digital strategy directly at caregivers, whom they empowered with knowledge on best practices for managing pediatric pain.

Chambers’s work is a good example of how including the patient (or, in this case, the caregiver) in the solution can improve results. Digital technologies, including social media platforms, provide opportunities to include people affected by mental health stigma in new solutions to address it.

As stigma researchers, my team and I recognize the potential value in providing stigma-reducing tools directly to patients and caregivers, as well as to the health professionals those tools are targeting. Bringing those groups together may provide better ways to tackle the stigmatizing practices and policies that still exist in health care.

Javeed Sukhera is an Associate professor, Western University

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Bushfires, Bots and Arson Claims: Australia Flung in the Global Disinformation Spotlight

In the first week of 2020, hashtag #ArsonEmergency became the focal point of a new online narrative surrounding the bushfire crisis.

The message: the cause is arson, not climate change.

Police and bushfire services (and some journalists) have contradicted this claim.

We studied about 300 Twitter accounts driving the #ArsonEmergency hashtag to identify inauthentic behaviour. We found many accounts using #ArsonEmergency were behaving “suspiciously”, compared to those using #AustraliaFire and #BushfireAustralia.

Accounts peddling #ArsonEmergency carried out activity similar to what we’ve witnessed in past disinformation campaigns, such as the coordinated behaviour of Russian trolls during the 2016 US presidential election.

Bots, trolls and trollbots

The most effective disinformation campaigns use bot and troll accounts to infiltrate genuine political discussion, and shift it towards a different “master narrative”.

Bots and trolls have been a thorn in the side of fruitful political debate since Twitter’s early days. They mimic genuine opinions, akin to what a concerned citizen might display, with a goal of persuading others and gaining attention.

Bots are usually automated (acting without constant human oversight) and perform simple functions, such as retweeting or repeatedly pushing one type of content.

Troll accounts are controlled by humans. They try to stir controversy, hinder healthy debate and simulate fake grassroots movements. They aim to persuade, deceive and cause conflict.

We’ve observed both troll and bot accounts spouting disinformation regarding the bushfires on Twitter. We were able to distinguish these accounts as being inauthentic for two reasons.

First, we used sophisticated software tools including tweetbotornot, Botometer, and Bot Sentinel.

There are various definitions for the word “bot” or “troll”. Bot Sentinel says:

Propaganda bots are pieces of code that utilize Twitter API to automatically follow, tweet, or retweet other accounts bolstering a political agenda. Propaganda bots are designed to be polarizing and often promote content intended to be deceptive… Trollbot is a classification we created to describe human controlled accounts who exhibit troll-like behavior.

Some of these accounts frequently retweet known propaganda and fake news accounts, and they engage in repetitive bot-like activity. Other trollbot accounts target and harass specific Twitter accounts as part of a coordinated harassment campaign. Ideology, political affiliation, religious beliefs, and geographic location are not factors when determining the classification of a Twitter account.

These machine learning tools compared the behaviour of known bots and trolls with the accounts tweeting the hashtags #ArsonEmergency, #AustraliaFire, and #BushfireAustralia. From this, they provided a “score” for each account suggesting how likely it was to be a bot or troll account.

We also manually analysed the Twitter activity of suspicious accounts and the characteristics of their profiles, to validate the origins of #ArsonEmergency, as well as the potential motivations of the accounts spreading the hashtag.

Who to blame?

Unfortunately, we don’t know who is behind these accounts, as we can only access trace data such as tweet text and basic account information.

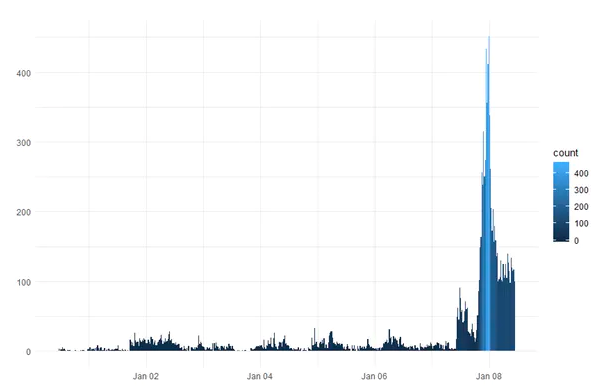

This graph shows how many times #ArsonEmergency was tweeted between December 31 last year and January 8 this year:

On the vertical axis is the number of tweets over time which featured #ArsonEmergency. On January 7, there were 4726 tweets. Author provided

Previous bot and troll campaigns have been thought to be the work of foreign interference, such as Russian trolls, or PR firms hired to distract and manipulate voters.

The New York Times has also reported on perceptions that media magnate Rupert Murdoch is influencing Australia’s bushfire debate.f

Weeding-out inauthentic behaviour

In late November, some Twitter accounts began using #ArsonEmergency to counter evidence that climate change is linked to the severity of the bushfire crisis.

Below is one of the earliest examples of an attempt to replace #ClimateEmergency with #ArsonEmergency. The accounts tried to get #ArsonEmergency trending to drown out dialogue acknowledging the link between climate change and bushfires.

We suspect the origins of the #ArsonEmergency debacle can be traced back to a few accounts. Author provided

The hashtag was only tweeted a few times in 2019, but gained traction this year in a sustained effort by about 300 accounts.

A much larger portion of bot and troll-like accounts pushed #ArsonEmergency, than they did #AustraliaFire and #BushfireAustralia.

The narrative was then adopted by genuine accounts who furthered its spread.

On multiple occasions, we noticed suspicious accounts countering expert opinions while using the #ArsonEmergency hashtag.

The inauthentic accounts engaged with genuine users in an effort to persuade them. author provided

Bad publicity

Since media coverage has shone light on the disinformation campaign, #ArsonEmergency has gained even more prominence, but in a different light.

Some journalists are acknowledging the role of disinformation bushfire crisis – and countering narrative the Australia has an arson emergency. However, the campaign does indicate Australia has a climate denial problem.

What’s clear to me is that Australia has been propelled into the global disinformation battlefield.

Keep your eyes peeled

It’s difficult to debunk disinformation, as it often contains a grain of truth. In many cases, it leverages people’s previously held beliefs and biases.

Humans are particularly vulnerable to disinformation in times of emergency, or when addressing contentious issues like climate change.

Online users, especially journalists, need to stay on their toes.

The accounts we come across on social media may not represent genuine citizens and their concerns. A trending hashtag may be trying to mislead the public.

Right now, it’s more important than ever for us to prioritise factual news from reliable sources – and identify and combat disinformation. The Earth’s future could depend on it.

Timothy Graham is a Senior Lecturer, Queensland University of Technology

Tobias R. Keller is a Visiting Postdoc, Queensland University of Technology

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

The Delta’s rich array of wildlife makes it a popular tourist destination. Ger Metselaar/Shutterstock

Botswana’s Okavango Delta is Created By a Delicate Balance, But For How Much Longer?

The Okavango Delta in northern Botswana is a mosaic of water paths, floodplains and arid islands. The delta sits in the Okavango river basin, which spans three African countries: Angola, Namibia and Botswana.

Because it’s an oasis, in a semi-arid area, it hosts a rich array of plants and attracts a huge variety of wildlife.

As a unique ecosystem, in 2014 it was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list and it is an iconic tourist destination, which generates 13% of Botswana’s GDP.

Aerial view of the Okavango Delta. Vadim Petrakov/Shutterstock

But it’s a fragile natural area. It’s controlled by deformations of the Earth’s crust over a long time (thousands to millions of years) and by annual water flows and evaporation. The size of the flooded delta from year to year varies between 3,500km² and 9,000km² because of weather fluctuations which control its water supply.

Any change to the processes that form the delta will have an impact on the wildlife and local economic activities. Its grassy floodplains are food for grazing animals in the dry period. Losses of this habitat will cause declines in wildlife and livestock. It’s therefore imperative to understand what creates and sustains the delta for the future management of the system.

We have conducted several studies that cover how the Okavango basin was formed and the way dissolved chemicals are withdrawn from the delta’s surface.

The dynamic history of the Okavango Delta’s waterways and floodplains tells us that the interplay between geology, water and plants makes the delta resilient, but vulnerable.

Some imminent changes are expected that are of concern. One is higher temperatures, which will boost evaporation and transpiration. Another is the pumping of water for irrigation in Namibia. Both of these changes will reduce the water needed to sustain the delta’s floodplains.

An oasis

The Okavango Delta is a generally flat area which is under constant change with phases of flooding and drying. A variety of geographical and natural processes have formed it and sustain it.

It’s in a depression which was created by fault lines cutting the Earth’s surface. This means water flows into it. The fault lines are created by the spread of the East African Rift – a major fracture, created over millions of years, which crosses the eastern part of Africa.

The origin of the islands in the delta is attributed to two mechanisms: the construction of termite mound spires; and formation of elevated ridges where former channels deposited sand. Both act as the starting point for vegetation to take root.

Termite mound in the delta. PIXEL to the PEOPLE/Shutterstock

The water supply comes from the Cubango and Cuito rivers in Angola. This reaches the delta between March and June and peaks in July. There’s also local rainfall in the Okavango area from November to February (about 450mm a year) which adds to this.

About 98% of the water that goes into the delta is eventually lost through evaporation and plant transpiration, when water moves through the plant and evaporates from leaves, stems and flowers.

Even though the subtropical sun generates intense evaporation, the delta’s water is fresh, not salty. This is surprising because water samples from the middle parts of the islands have very high chemical and salt concentrations. This chemical concentration occurs in thousands of islands.

The reason the water is fresh is that trees on the edges of the islands have created a barrier of natural filters between the inner part of the islands and the floodplain.

Possible changes

The Okavango Delta is continually being shaped by complex interactions of natural processes. If something happens to change the balance of these processes, it could destabilise the system.

The most important dynamic for the delta is inflowing water. The two main rivers in Angola, the Cubango and the Cuito, join to form the Okavango river, which feeds the delta. These two rivers are hydrologically quite different. The Cubango, to the west, first flows rapidly down steep, narrow paths characterised by incised valleys, rapids, waterfalls and valley swamps. The Cuito, to the east, with shallow valleys and large floodplains, gets its water from groundwater seepage.

The manipulation of these rivers – in the form of dams and irrigation – will affect the water flow and change its annual distribution. Both of these form part of current and future development planning in Angola and Namibia.

A decrease in water supply will affect the vegetation growth and the wildlife. An increase in water would inundate the islands and could dissolve the salts at the centre of them, releasing chemical elements that would change the water quality.

In addition to declines in water flow induced by global warming and human activities, ground deformation is also happening because of shifting continental plates. This could change the paths of the water flowing by changing the ground slopes. Measurements of ground deformation with Global Positioning Systems displays reveal very slight changes in local slopes that can modify the paths of the water flowing to the delta.

To sustain the Okavango Delta it’s imperative that management integrate all the components of the system. All governments are involved and must integrate scientific expertise, from upstream catchment to downstream Delta.

Michael Murray-Hudson is a Senior Research Fellow, Okavango Research Institute, University of Botswana

Olivier Dauteuil is a Directeur de Recherche au CNRS, Université Rennes 1

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

KASHMIR — A Lost Paradise

In one of the most beautiful places on Earth, the conflict in Kashmir – which have been largely forgotten by the world – has raged on since 1947. What was once a paradise, Kashmir Valley is now the forgotten epicenter of war, human-rights violations and a true representation of what it looks like to struggle for peace and freedom. Watch this short video about the beauty and conflict of Kashmir.

Read MoreThe Lost Neighborhood Under New York's Central Park

Before Central Park was built, a historically black community was destroyed.If you’ve been to New York, you’ve probably visited Central Park. But there’s a part of its story you won't see. It’s a story that goes back to the 1820s, when that part of New York was largely open countryside. Soon it became home to about 1,600 people. Among them was a predominantly black community that bought up affordable plots to build homes, churches and a school. It became known as Seneca Village. And when Irish and German immigrants moved in, it became a rare example at the time of an integrated neighborhood. Everything changed on July 21, 1853. New York took control of the land to create what would become the first major landscaped park in the US -- they called it “The Central Park.”

After Being Partially Paralyzed, Hannah Gavios Is Completing Marathons

Hannah Gavios runs using crutches. The native New Yorker calls it “crutching” or “going for a crutch.” An avid runner since high school, Gavios suffered a spinal cord injury after a horrific attack in 2016 that left her partially paralyzed. Unable to imagine a life without running, Gavios learned how to run in a different way. She also became a certified yoga instructor and began studying Krav Maga. In 2019, she completed the 2019 New York City Marathon. “No matter how much you’ve lost in your life, there’s always gains,” Gavios says.

Thanks to algorithms, outrage often snowballs. Andrii Yalanskyi/Shutterstock.com

Hate Cancel Culture? Blame Algorithms

“Cancel culture” has become so pervasive that even former President Barack Obama has weighed in on the phenomenon, describing it as an overly judgmental approach to activism that does little to bring about change.

For the uninitiated, here’s a quick primer on the phenomenon: An individual or an organization says, supports or promotes something that other people find offensive. They swarm, piling on the criticism via social media channels. Then that person or company is largely shunned, or “canceled.”

It happened to Chick-fil-A when its ties to organizations such as Focus on the Family invited backlash from LGBTQ activists; it happened to YouTube influencer James Charles, who was accused of betraying his former mentor and lost millions of followers; and it happened to Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross after people learned he had held a fundraiser for President Trump.

Outrage can spread so quickly on social media that companies or individuals who don’t adequately respond to a mishap – intentional or not – can face swift backlash. You can send a thoughtless tweet before boarding a flight and, upon landing, realize you’ve become the target of global ire.

A lot of attention has been given to repercussions of cancel culture on celebrities, from JK Rowling, to Kevin Hart to Lena Dunham.

Less talked about is the way algorithms actually perpetuate cancel culture.

Algorithms love outrage

My own research has shown how content that sparks an intense emotional response – positive or negative – is more likely to go viral.

Out of millions of tweets, posts, videos and articles, social media users can be exposed to only a handful. So platforms write algorithms that curate news feeds to maximize engagement; social media companies, after all, want you to spend as much time on their platforms as possible.

Outrage is the perfect negative emotion to attract attention and engagement – and algorithms are primed to pounce. One person tweeting her outrage would normally fall largely on deaf ears. But if that one person is able to attract enough initial engagement, algorithms will extend that individual’s reach by promoting it to like-minded individuals. A snowball effect occurs, creating a feedback loop that amplifies the outrage.

Often, this outrage can lack context or be misleading. But that can work in its favor. In fact, I’ve found that misleading content on social media tends to lead to even more engagement than verified information.

So you can write an immature tweet as a teenager, someone can dig it up, express outrage, conveniently leave out that it’s from seven or eight years ago, and the algorithms will nonetheless amplify the reaction.

All of a sudden, you’re canceled.

Hart goes down

We saw this dynamic recently play out with actor Kevin Hart.

Once it was announced that Hart would be the host for the 2019 Academy Awards, Twitter users plumbed a series of homophobic tweets from 2009 to 2011 and started sharing them. Few were aware Hart had tweeted about homosexuality. The outrage was swift.

Hart’s unapologetic response on Instagram inflamed the online anger.

Algorithms anticipate what users want based on detailed information about their preferences. All of a sudden, those most likely to be upset by Hart’s homophobic remarks were having tweets about them splashed across their feeds.

Algorithms amplified the outrage over Kevin Hart’s homophobic comments – and his opportunity to host the Oscars went up in smoke. Jordan Strauss/Invision/AP

Within a day of Hart’s Instagram post, the actor announced he would withdraw from hosting.

Cancel culture is just one outgrowth of social media algorithms.

More broadly, people have criticized how algorithms such as YouTube’s actively promote divisive posts in order to suck people into spending more time online.

In 2018, a British Parliament committee report on fake news criticized Facebook’s “relentless targeting of hyper-partisan views, which play to the fears and prejudices of people.”

Algorithms encourage second acts

Paradoxically, the same algorithmic forces that buttress cancel culture can actually rehabilitate canceled entertainers.

A few months after the Hart controversy, Netflix decided to produce two shows featuring the comedian.

Why would Netflix expose itself to criticism by elevating a supposedly canceled celebrity?

Because it knew that there would be an audience for Hart’s comedy – that, in certain circles, the fact that he had been canceled made him that much more appealing.

Like social media platforms, Netflix also deploys algorithms. Because Netflix has a massive library of content, it deploys algorithms that take into account users’ prior viewing choices and preferences to recommend specific shows and movies.

Maybe these users are die-hard Hart fans. Or maybe they’re inclined see Hart as a victim of political correctness. Either way, Netflix has granular data about which users would be predisposed to watching a show about Hart, despite the fact that he had been nominally canceled.

On Netflix’s end, there’s little risk. Netflix probably knows, on some level, which of its subscribers are likely to be offended by Hart. So it simply won’t promote Hart’s show to those people. At the same time, partnering with controversial brands and individuals can be good for business.

Together, the phenomenon of cancel culture is an illustration of the weird ways algorithms and social media can upend, distort and rehabilitate the lives and careers of celebrities.

Anjana Susarla is a Associate Professor of Information Systems, Michigan State University

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Many boys are taught they shouldn’t do ‘girl things’ like ballet. UvGroup/Shutterstock.com

How Toys Became Gendered – and Why It’ll Take More Than a Gender-Neutral Doll to Change How Boys Perceive Femininity

Parents who want to raise their children in a gender-nonconforming way have a new stocking stuffer this year: the gender-neutral doll.

Announced in September, Mattel’s new line of gender-neutral humanoid dolls don’t clearly identify as either a boy or a girl. The dolls come with a variety of wardrobe options and can be dressed in varying lengths of hair and clothing styles.

But can a doll – or the growing list of other gender-neutral toys – really change the way we think about gender?

Mattel says it’s responding to research that shows “kids don’t want their toys dictated by gender norms.” Given the results of a recent study reporting that 24% of U.S. adolescents have a nontraditional sexual orientation or gender identity, such as bisexual or nonbinary, the decision makes business sense.

As a developmental psychologist who researches gender and sexual socialization, I can tell you that it also makes scientific sense. Gender is an identity and is not based on someone’s biological sex. That’s why I believe it’s great news that some dolls will better reflect how children see themselves.

Unfortunately, a doll alone is not going to overturn decades of socialization that have led us to believe that boys wear blue, have short hair and play with trucks; whereas girls like pink, grow their hair long and play with dolls. More to the point, it’s not going to change how boys are taught that masculinity is good and femininity is something less – a view that my research shows is associated with sexual violence.

Girl toys tend to be pink. AP Photo/Nick Ut

Pink girls and blue boys

The kinds of toys American children play with tend to adhere to a clear gender binary.

Toys marketed to boys tend to be more aggressive and involve action and excitement. Girl toys, on the other hand, are usually pink and passive, emphasizing beauty and nurturing.

It wasn’t always like this.

Around the turn of the 20th century, toys were rarely marketed to different genders. By the 1940s, manufacturers quickly caught on to the idea that wealthier families would buy an entire new set of clothing, toys and other gadgets if the products were marketed differently for both genders. And so the idea of pink for girls and blue for boys was born.

Today, gendered toy marketing in the U.S. is stark. Walk down any toy aisle and you can clearly see who the audience is. The girl aisle is almost exclusively pink, showcasing mostly Barbie dolls and princesses. The boy aisle is mostly blue and features trucks and superheroes.

Breaking down the binary

The emergence of a gender-neutral doll is a sign of how this binary of boys and girls is beginning to break down – at least when it comes to girls.

A 2017 study showed that more than three-quarters of those surveyed said it was a good thing for parents to encourage young girls to play with toys or do activities “associated with the opposite gender.” The share rises to 80% for women and millennials.

But when it came to boys, support dropped significantly, with 64% overall – and far fewer men – saying it was good to encourage them to do things associated with girls. Those who were older or more conservative were even more likely to think it wasn’t a good idea.

Reading between the lines suggests there’s a view that traits stereotypically associated with men – such as strength, courage and leadership – are good, whereas those tied to femininity – such as vulnerability, emotion and caring – are bad. Thus boys receive the message that wanting to look up to girls is not OK.

And many boys are taught over and over throughout their lives that exhibiting “female traits” is wrong and means they aren’t “real men.” Worse, they’re frequently punished for it – while exhibiting masculine traits like aggression are often rewarded.

Breaking down gender norms – for girls

A 2017 survey shows a greater share of adults think it's okay for girls to do "boy things" than for boys to do "girl things."

How this affects sexual expectations

This gender socialization continues into emerging adulthood and affects men’s romantic and sexual expectations.

For example, a 2015 study I conducted with three co-authors explored how participants felt their gender affected their sexual experiences. Roughly 45% of women said they expected to experience some kind of sexual violence just because they are women; whereas none of the men reported a fear of sexual violence and 35% said their manhood meant they should expect pleasure.

And these findings can be linked back to the kinds of toys we play with. Girls are taught to be passive and strive for beauty by playing with princesses and putting on makeup. Boys are encouraged to be more active or even aggressive with trucks, toys guns and action figures; building, fighting and even dominating are emphasized. A recent analysis of Lego sets demonstrates this dichotomy in what they emphasize for boys – building expertise and skilled professions – compared with girls – caring for others, socializing and being pretty. Thus, girls spend their childhoods practicing how to be pretty and care for another person, while boys practice getting what they want.

This results in a sexual double standard in which men are the powerful actors and women are subordinate. And even in cases of sexual assault, research has shown people will put more blame on a female rape victim if she does something that violates a traditional gender role, such as cheating on her husband – which is more accepted for men than for women.

A 2016 study found that adolescent men who subscribe to traditional masculine gender norms are more likely to engage in dating violence, such as sexual assault, physical or emotional abuse and stalking.

Mattel’s new line of dolls come with clothes for all genders. Mattel

Teaching gender tolerance

Mattel’s gender-neutral dolls offer much-needed variety in kids’ toys, but children – as well as adults – also need to learn more tolerance of how others express gender differently than they do. And boys in particular need support in appreciating and practicing more traditional feminine traits, like communicating emotion or caring for someone else – skills that are required for any healthy relationship.

Gender neutrality represents the absence of gender – not the tolerance of different gender expression. If we emphasize only the former, I believe femininity and the people who express it will remain devalued.

So consider doing something gender-nonconforming with your children’s existing dolls, such as having Barbie win a wrestling championship or giving Ken a tutu. And encourage the boys in your life to play with them too.

Megan K. Maas is a Assistant Professor of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

The Nile river in Cairo. Grant Faint/Getty Images

Nile Basin States Must Build a Flexible Treaty. Here’s How..

Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt are a step closer to resolving their disputes over the filling and operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. The dam – a huge project on one of the River Nile’s main tributaries, the Blue Nile in Ethiopia – is designed to generate 6,000 megawatts of electricity. Its reservoir can hold more than 70 billion cubic metres of water. That’s nearly equal to half of the Nile’s annual flow.

Filling the immense reservoir will diminish the flow of the Nile water.

Tensions have been particularly acute between Egypt and Ethiopia because more than 80% of the water reaching Egypt comes from the Blue Nile.

Despite decades of concerted effort, no comprehensive deal between all 11 countries that share the Nile’s river basin has ever been reached. But, after rigorous discussions in the US, Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan issued a joint statement that lays the framework for a final agreement. The three countries agreed that the dam would be filled in stages, and that it would only take place in the wet season.

The framework also underscored the need for any agreement to be open to changes. This is important because the three countries must consider changes in weather patterns, among other factors, while developing the final draft.

Instead of allocating the Nile waters based on the assumption of a fixed, and often too optimistic, perpetual water supply, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt should do it in accordance with the social, economic and changing weather conditions in the Nile basin.

This is extremely important as existing studies and climate change models commonly predict potential changes in weather patterns and temperature.

Changing weather patterns

Studies suggest that there is likely to be an increase in the basin’s average annual temperature. This would lead to greater loss of water due to evaporation. Changes are also expected in the future rainfall, river flow and water availability in the Nile Basin, although there’s less certainty about these.

But there’s enough evidence to point to the need for flexibility around agreements on how the dam will be filled. For example, there must be allowances to respond to scenarios of increased water availability and flooding, or water scarcity and drought.

Building flexible and resilient legal and institutional arrangements into the new treaty is therefore key. These include drought provisions, flexible allocation strategies, amendment and review procedures, termination clauses and recognised river basin organisations.

Flexibility in watercourse treaties, due to the unknown effects of climate change, has been recommended by leading scholars in the field such as Stephen McCaffrey and Itay Fischhendler.

Drought provisions

Drought provisions are a common way to improve the flexibility of treaties. Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt can include special provisions that allow for exceptional circumstances, like severe drought.

To deal with the hardships of the projected extreme drought years, the three countries will need to build more reservoirs and storage capacity. But given the tension the dam has caused, finding agreement on this is likely to be challenging. This is all the more reason to include specific clauses in the treaty about storage.

There should also be flexibility in how much water is allocated, instead of a fixed amount. There are a couple of ways this can be achieved.

A simple way is to require Ethiopia to deliver a minimum flow to Sudan and Egypt to maintain human health and basic ecological functions.

The other option would be a percentage allocation. This would share possible water deficiencies, and surplus, proportionally among the three countries. Each country would get its agreed share of the total in a given year.

This would be the better option because it would respond to both wet and dry conditions.

Amendments and reviews

To make the treaty flexible, it’s also important to provide for amendments and reviews of processes. In this way countries could address unforeseen circumstances.

For instance, Ethiopia promised, under the joint statement, that it will fill the dam’s reservoir during the wet season, generally from July to September. But the wet and dry seasons could change.

The treaty can establish what might “trigger” adjustments or have set times for when a review should occur.

It must also have a termination clause which allows any riparian state to terminate the agreement, with a notice period.

River basin organisations

Managing water across boundaries needs river basin organisations. These are entities entrusted to manage water resources at the basin scale. They’re important because they can help introduce a level of flexibility in the arrangements between the riparian states.

A good example of how this can be done is the role played by a river basin organisation charged with applying the 1944 Colorado Treaty. The organisation was composed of an engineer commissioner from both parties – the US and Mexico – and was able to adapt, amend and extend institutional arrangements, including the main treaty.

In the case of the Nile basin, Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt have two options.

They can establish a joint body in the treaty that will manage the operations of dams in their respective countries. But this would exclude the other eight Nile riparian countries.

The other, and arguably better, option is to manage all dams through the Nile Basin Commission – an organisation envisaged in the Cooperative Framework Agreement. This was an attempt by riparian states to prepare a basin-wide framework to regulate the inter-state use and management of the Nile River. All the Nile basin states except Egypt and Sudan agreed to it.

This organisation has a wide range of powers, which include the ability to examine and decide how water is best used and distributed. Egypt and Sudan must accede to the framework agreement. And the treaty must empower the body to manage the filling and operation of the dams and reservoirs in the three countries.

Mahemud Tekuya is a JSD/Ph.D candidate, University of the Pacific

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Roll call at the Buchenwald concentration camp. Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com

Why Legislation Is Needed to Make Holocaust Education More Prominent in Public Schools

1. Why is the ‘Never Again Education Act’ needed?

Research shows that adults and millennials in the United States have significant gaps in what they know about the Holocaust.

For instance, while 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust, 41% of millennials believe the number is 2 million or fewer.

The Never Again Education Act will seek to address these kinds of gaps in knowledge by making Holocaust education a bigger and more important part of education in various middle and high schools across the country. The legislation provides US$2 million a year, for five years, to be given to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The museum will distribute the money to various teachers and educational leaders who apply for grants to teach kids about the Holocaust.

Schools without any Holocaust education in place will get top consideration. The museum must also increase digital and print educational resources, do more to help teachers and future schoolteachers become more knowledgeable about the Holocaust and teach it more effectively, and conduct research on the impact of Holocaust education.

2. Why can’t schools just teach Holocaust history without a special law?

History in general is not a tested subject like math, reading and writing. And the Holocaust itself is often limited, as I found in forthcoming research, to one or two class periods a year – usually as part of a lesson about World War II more broadly.

As a result, teachers rely heavily on textbooks when teaching about the Holocaust and end up spending a minimum amount of class time on the subject. I have found that teachers can be uncomfortable teaching about the Holocaust because they worry about their lack of knowledge on the subject. They may also be uncertain of how to relay such intense information to their students.

3. How big a problem is Holocaust denial and distortion?

Holocaust denial and distortion do similar things.

Holocaust denial denies that the Holocaust ever happened. Holocaust distortion minimizes the events that took place. While both have long been present in both American and global conversations, recently these have been at the forefront of discussions in new ways.

For instance, Holocaust denial has taken place in schools. It has even occurred at schools with state-mandated Holocaust education, such as Florida, where a principal told a parent that he wasn’t permitted as a district employee to say the Holocaust was a “factual, historical event.” In New Jersey, the first state to require Holocaust education, a teacher urged students to question the Holocaust.

Unfortunately, social media enables denial and distortion to proliferate in unprecedented ways.

4. Why doesn’t the act deal with atrocities that took place on US soil?

The short answer is that this proposed law is intended to improve the quality of Holocaust education, specifically.

A skilled teacher can, and should, make connections between the Holocaust and other genocides and mass atrocities by looking at recurring historical themes including – but not limited to – racism, xenophobia and nationalism. Additional legislation, as well as a hard and honest look at America’s complicated history, would be helpful next steps.

5. What evidence is there that Holocaust education can reduce racial hatred?

There is some evidence that Holocaust education will reduce anti-Semitism in particular and all kinds of bias in general.

This work may not be easy, but helpful practices include using precise language in classrooms, having a clear set of goals in teaching and using age-appropriate lessons.

Jennifer Rich is an Assistant Professor; Director, Rowan Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Rowan University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

The Diet That Helps Fight Climate Change

You don’t have to go vegan to fight climate change. Research shows that small changes to our diets can make big differences. Climate Lab is produced by the University of California in partnership with Vox. Hosted by conservation scientist Dr. M. Sanjayan, the videos explore the surprising elements of our lives that contribute to climate change and the groundbreaking work being done to fight back. Featuring conversations with experts, scientists, thought leaders and activists, the series demystifies topics like nuclear power, food waste and online shopping to make them more approachable and actionable for those who want to do their part. Sanjayan is an alum of UC Santa Cruz, a Visiting Researcher at UCLA and the CEO of Conservation International.

Hip-hop officially became the most popular music genre in 2018 and continued its reign in 2019, according to Nielsen Music. Lev Radin/Shutterstock.com

Why Hip-Hop Belongs in Today’s Classrooms

When Cassie Crim, a high school math teacher in Joliet, Illinois, introduced herself to her advanced algebra students in 2017, she did it through a rap video.

Using a rendition of Cardi B’s “Bodack Yellow,” renamed “Codack Yellow,” Crim referenced math terms and laid down classroom expecations:

“These exponents, these is ratios, these is power rules Algebra and a lil’ trig, I don’t wanna choose And I’m quick to take a couple (points) off so don’t get comfortable”

With rap music continuing to rule as America’s most popular music genre for a second straight year in 2019, according to Nielsen Music’s annual report, it makes sense for educators to use rap music to reach students who might otherwise not find a subject relevant. And Crim is by no means the only teacher who is doing just that.

In Pasadena, California, Manuel Rustin, a social studies teacher at John Muir High School, uses rap songs to get students to make meaning of current events and history through a course entitled “Urban Culture and Society.”

At Detroit’s Frederick Douglass Academy, Quan Neloms has students search the lyrics of their favorite rap songs for “college-level vocabulary and references to key events and concepts from American history.”

Collectively, the three teachers represent part of a new generation of educators who embrace a form of teaching known as Hip Hop Pedagogy. It’s a form of teaching that takes the most popular genre of music in the U.S. and uses it to foster success in the classroom.

But is it paying off?

As one who has taught Hip Hop Pedagogy courses to K-12 teachers and instructors in higher ed for the last 10 years, I believe hip-hop has the potential to connect students to important subjects they might otherwise dismiss. But it all depends how it is done.

In my Hip Hop Pedagogy courses, K-12 teachers and college instructors learn how to tap into the richness of hip-hop culture to engage students in topics that range from Shakespeare to neuroscience. But I also stress the need to be authentic – in other words, don’t lie about where you are from – and steer clear of gimmicky hip-hop instructional strategies, such as parroting hip-hop lingo out of context, or showing a random rap video that has nothing to do with the course subject.

Hip-hop through the years

Hip-hop scholar Marc Lamont Hill. Wikimedia Commons

Hip-hop in America’s classrooms is not new. For the past decade or two, scholars such as Marc Lamont Hill, Chris Emdin and Jeff Duncan-Andrade have explored the impact and effectiveness of hip-hop in educational settings.

Collectively, their research has found that hip-hop can be used to teach critical thinking skills, critical literacy, media literacy skills, STEM skills, critical consciousness and more.

Hip-hop has made significant inroads into higher education as well.

Hip-hop in higher ed

Hip-hop academic scholarship goes back at least as far as Tricia Rose’s groundbreaking 1994 book, “Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America.” Since then, numerous hip-hop education books have been written. More than 300 colleges and universities have offered courses on hip-hop. The University of Arizona offers a minor in Hip Hop Studies, and McNally Smith College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, offers a hip-hop diploma, which includes 45 credits and three semesters of hip-hop music production, language and history courses.

These developments are no light feat. In order for hip-hop to reach the level of prevalence that it enjoys on today’s educational landscape – at least 150 educators at the K-12 level were using hip-hop in their class in 2011, the last time a hip-hop education “census” took place – it had to overcome the skepticism of critics who questioned its validity in educational spaces. How would hip-hop explain its controversial history of glorifying violence, consumption and misogyny? Is hip-hop music appropriate for classrooms?

But hip-hop, despite what some may view as its flaws, is a mirror of the complexity of society. Hip-hop did not invent violence, excessive consumerism and mistreatment of women. What it does is provide a platform to talk about these issues.

Breaking it down

That’s what Rustin, the social studies teacher in Pasadena, did when he used rapper Childish Gambino’s provocative video “This is America” to get students to critically analyze the state of affairs in American society. As one student stated in an article about watching the video in class, “It relies on the shock value of violence and capitalizes on our society’s growing numbness to seeing black bodies being brutalized – it’s exploitative.”

Drawing conclusions from hip-hop lyrics requires a certain level of critical analysis, one of the course expectations. Thus, in line with state education standards, Rustin’s course requires college-level writing, reading and critical thinking. Alums of Rustin’s class have indicated that discussions in the class not only increased their critical thinking skills but prepared them for college courses.

Other teachers who use hip-hop in the classroom have achieved similar results. For instance, Crim, the Joliet math teacher, said she noticed improved student engagement after her video, as well as “an increase in performance from one unit test to the next.”

Neloms, the Detroit educator who had his student search rap songs for college level vocabulary, did so after only 33 percent of his students passed a vocabulary exam. After he introduced his class to Rhymes with Reason, an “interactive online series that teaches college-level vocabulary and U.S. history concepts using hip-hop lyrics” rooted in African American speech, Neloms documented a “dramatic increase” in his students’ test scores.

I think similar results could be achieved by more teachers if they tap into the richness of hip-hop culture to reach today’s students. Many students are already forming their views of society and the world based on the lyrics of their favorite rap artists. It only makes sense to infuse what they’re already listening to into the class so that – at the very least – there’s a common point of reference.

Nolan Jones is a associate Adjunct Professor, Mills College.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Water purification at a modern urban wastewater treatment plant involves removing undesirable chemicals, suspended solids and gases from contaminated water. arhendrix/Shutterstock.com

Microwaving Sewage Waste May Make It Safe to Use as Fertilizer on Crops

My team has discovered another use for microwave ovens that will surprise you.

Biosolids – primarily dead bacteria – from sewage plants are usually dumped into landfills. However, they are rich in nutrients and can potentially be used as fertilizers. But farmers can’t just replace the normal fertilizers they use on agricultural soil with these biosolids. The reason is that they are often contaminated with toxic heavy metals like arsenic, lead, mercury and cadmium from industry. But dumping them in the landfills is wasting precious resources. So, what is the solution?

I’m an environmental engineer and an expert in wastewater treatment. My colleagues and I have figured out how to treat these biosolids and remove heavy metals so that they can be safely used as a fertilizer.

How treatment plants clean wastewater

Wastewater contains organic waste such as proteins, carbohydrates, fats, oils and urea, which are derived from food and human waste we flush down in kitchen sinks and toilets. Inside treatment plants, bacteria decompose these organic materials, cleaning the water which is then discharged to rivers, lakes or oceans.

The bacteria don’t do the work for nothing. They benefit from this process by multiplying as they dine on human waste. Once water is removed from the waste, what remains is a solid lump of bacteria called biosolids.

This is complicated by the fact that wastewater treatment plants accept not only residential wastewater but also industrial wastewater, including the liquid that seeps out of solid waste in landfills – called leachate – which is contaminated with toxic metals including arsenic, lead, mercury and cadmium. During the wastewater treatment process, heavy metals are attracted to the bacteria and accumulate on their surfaces.

If farmers apply the biosolids at this stage, these metals will separate from the biosolids and contaminate the crop for human consumption. But removing heavy metals isn’t easy because the chemical bonds between heavy metals and biosolids are very strong.

Gang Chen microwaves some biosolids, separating the organic material from the toxic metals. Gang Chen/FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, CC BY-SA

Microwaving waste releases heavy metals

Conventionally, these metals are removed from biosolids using chemical methods involving acids, but this is costly and generates more dangerous waste. This has been practiced on a small scale in some agricultural fields.

After a careful calculation of the energy requirement to release the heavy metals from the attached bacteria, I searched around for all the possible energy sources that can provide just enough to break the bonds but not too much to destroy the nutrients in the biosolids. That’s when I serendipitously noticed the microwave oven in my home kitchen and began to wonder whether microwaving was the solution.

My team and I tested whether microwaving the biosolids would break the bonds between heavy metals and the bacterial cells. We discovered it was efficient and environmentally friendly. The work has been published in the Journal of Cleaner Production. This concept can be adapted to an industrial scale by using electromagnetic waves to produce the microwaves.

This is a solution that should be beneficial for many people. For instance, managers of wastewater treatment plants could potentially earn revenue by selling the biosolids instead of paying disposal fees for the material to be dumped to the landfills.

It is a better strategy for the environment because when biosolids are deposited in landfills, the heavy metals seep into landfill leachate, which is then treated in wastewater treatment plants. The heavy metals thus move between wastewater treatment plants and landfills in an endless loop. This research breaks this cycle by separating the heavy metals from biosolids and recovering them. Farmers would also benefit from cheap organic fertilizers that could replace the chemical synthetic ones, conserving valuable resources and protecting the ecosystem.

Is this the end? Not yet. So far we can only remove 50% of heavy metals but we hope to shift this to 80% with improved experimental designs. My team is currently conducting small laboratory and field experiments to explore whether our new strategy will work on a large scale. One lesson I would like to share with everyone: Be observant. For any problem, the solution may be just around you, in your home, your office, even in the appliances you are using.

Biosolids after collection from a waste treatment facility. Gang Chen/FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, CC BY-SA

Gang Chen is a Professor of Civil & Environmental Engineering, FAMU-FSU College of Engineering

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

A woman walks through the shattered streets of Port-au-Prince a few weeks after the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake slammed the country, which has still not recovered despite billions of dollars being spent. Rodrigo Abd/AP Photo, File

A Decade After the Earthquake, Haiti Still Struggles to Recover

More than 300,000 people were killed, several hundred thousand were injured and nearly 1.5 million were left homeless when magnitude 7 earthquake hit Haiti on Jan. 12, 2010.

On that day, the workspace that my colleague Joseph Jr Clorméus, who co-authored this article, usually occupied at the Ministry of National Education completely collapsed. He witnessed an apocalyptic spectacle: colleagues had lost their lives while others were having limbs amputated to escape certain death under the rubble. Outside, corpses littered the streets of the capital while the horrifying spectacle of blood mixed with concrete and dust offered itself to the desolate gaze of a traumatized population.

Ten years later, Haiti hasn’t recovered from this disaster, despite billions of dollars being spent in the country.

Two main factors explain, in our view, the magnitude of this tragedy: the weakness of Haitian public institutions and the disorganization of international aid, particularly from NGOs.

A few months after the earthquake, a girl walks on debris as she uses the structure of a damaged building in Port-au-Prince to air-dry clothes. AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos

The weakness of the Haitian state

Haiti is vulnerable to earthquakes. Historically, they have been managed by the military, which played an important role in both national development and natural disaster management. But the speedy dismantling of the national army under Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s presidency did not allow for the transfer of the army’s natural disaster management skills to other civilian public institutions.

Indeed, a great deal of know-how disappeared. Despite the presence of several government bodies that had tried to develop skills in relation to earthquakes, no reliable operational body was able to manage the institutional vacuum left by the army. Today, Haiti remains very vulnerable to natural disasters on its territory.

The succession of unstable governments over the past four decades hasn’t helped either. These have significantly weakened the central administration, which then had little capacity to manage and control the country’s territory.

For example, Port-au-Prince, a city originally designed for 3,000 people, was home to almost a million. Ten years later, we can only note that nothing has really changed in this respect. The Haitian state has shown itself incapable of decentralizing and developing its rural environment, which is experiencing an exodus year after year.

The capital and its surroundings are overpopulated and there are no real urban planning policies to impose standards and counter the anarchic constructions that proliferate the city. In this context, any major earthquake could only lead to the disastrous consequences that the country has experienced.

Another problem: in 2010, the Haitian public administration, far from having been reformed, was mainly concerned with collecting taxes on property without any real control over the territory.

The combination of overcrowding, chaotic urban development without a regional development policy, a flagrant lack of resources to intervene on its territory and the skills of its staff has meant that the Haitian public administration has never been able to anticipate the impacts of an earthquake.

People stand in the rubble of a collapsed building in Port-au-Prince following the earthquake. AP Photo/Rodrigo And, File

Disorganized international aid

The weakness of the Haiti’s public administration is compounded by the disorganization of international aid. Following a decree adopted in 1989 (which amended Article 13 of the 1982 law governing NGOs), responsibility for the co-ordination and supervision of NGO activities on the territory of the Republic of Haiti was entrusted to the Ministry of Planning and External Co-operation (MPCE).

In the aftermath of the earthquake, many studies reported on the presence of thousands of NGOs in the country. However, on its official list, the MPCE recognized barely 300 of them. It can therefore be concluded that the majority of these NGOs were operating in near obscurity.

Several studies have also shown, and we’ve seen on the ground, that the international community’s assistance deployed immediately after the earthquake failed to meet a humanitarian challenge of such magnitude. There was no co-ordination in the interventions of friendly countries in order to optimize the efforts on behalf of the victims. There was great humanitarian disorganization and even a failure on the part of the international community, which had to improvise ineffectively to co-manage a disaster.

With a presence on the ground as early as 2012, we’ve observed that the majority of NGOs arrived in Haiti not to respond to a need expressed by the Haitian government, but rather to serve their own interests, as Dr. Joanne Liu, former president of Médecins Sans Frontières, reports.

There was no co-ordination between them, nor was there any co-ordination with the government. Furthermore, although UN forces deployed with MINUSTAH were present in Haiti, the forces were fragmented and operated under often incompatible models and values. Aid was inefficient, even harmful. The scandal of the reintroduction of cholera in Haiti underscores this reality.

A Peruvian peacekeeper tries to control a crowd during the distribution of food for earthquake survivors at a warehouse in Port-au-Prince on Jan. 19, 2010. UN aid has been largely ineffective. AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos, File

Post-earthquake

Despite the fact that billions of dollars had been spent in the country, according to international reports, five years after the disaster, debris was still lying in the streets, thousands of people were still living in refugee camps and the majority of public buildings had not been rebuilt.

All of this testifies to the serious difficulties of co-ordination on the ground.

A decade later, the challenges are still immense for Haiti since it must develop construction policies that fit into a certain vision of urban planning. It must also rebuild the archives of public institutions that have been damaged or have disappeared, and it must help post-earthquake generations learn from the past, develop and implement an emergency plan for natural disasters, and design and implement policies and spaces adapted for people with disabilities.

Today, international development practices are seen to be based on a wealth accumulation perspective, giving priority to private sector interests. Canada’s initiatives to direct its aid to the development of the mining sector and free-trade zones in Haiti are evidence of this.

What’s more, Canada’s decision to freeze funding for new projects in Haiti raises several questions: why leave Haiti in such a difficult position? Is the decision intended to make the Haitian state face up to its responsibilities or simply to take the Canadian government off the hook for the failure of international aid in that country? Is this an admission of powerlessness in the face of the profound institutional weaknesses in Haiti?

As we look back at Jan. 12, 2010, we raise a question as troubling as it is fundamental: Has the Haitian government and the international community really learned any lessons from the earthquake?

Jean-François Savard is a professeur agrégé, École nationale d'administration publique (ENAP)

Emmanuel Sael is a doctorant en administration publique, École nationale d'administration publique (ENAP)

Joseph Jr Clormeus is a doctorate candidate in public administration, École nationale d'administration publique (ENAP)

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Academic Freedom: Repressive Government Measures Taken Against Universities in More Than 60 Countries

Universities around the world are increasingly under threat from governments restricting their ability to teach and research freely. Higher education institutions are being targeted because they are the home of critical inquiry and the free exchange of ideas. And governments want to control universities out of fear that allowing them to operate freely might ultimately limit governmental power to operate without scrutiny.

My recent report, co-authored with researcher Aron Suba for the International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law, has found evidence of restrictive and repressive government measures against universities and other higher education institutions in more than 60 countries.

This includes government interference in leadership and governance structures to effectively create state-run institutions that are particularly vulnerable to government actions. It also includes the criminalisation of academics for their work as well as the militarisation and securitisation of campuses through the presence of armed forces or surveillance by security services. We also found evidence that students have been prevented from attending university because of their parents’ political beliefs, while others have been expelled or even imprisoned for expressing their own opinions.

Some of the more shocking examples of repressive practices have been widely publicised, such as the firing of thousands of academics and jailing of others in Turkey. But much of what is happening is at an “administrative” level – against individual institutions or the entire higher education system.

There are examples of governments that restrict access to libraries and research materials, censor books and prevent the publication of research on certain topics. Governments have also stopped academics travelling to meet peers, and interfered with curricula and courses. And our research also found governments have even interfered in student admissions, scholarships and grades.

Repression, intimidation

Hungary provides a particularly glaring recent example of government interference with university autonomy. The politicised targeting of the institution I work at –- Central European University –- has been well documented. But the government has also recently acted against academic life in the country more broadly. It has effectively prohibited the teaching of a course (gender studies) and taken control of the well-regarded Hungarian Academy of Social Sciences.

What makes the Hungarian example especially disturbing is that it is happening within the European Union – with seemingly no consequences for the government. This is despite the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights which states that: “The arts and scientific research shall be free of constraint. Academic freedom shall be respected.” Meanwhile the Hungarian government still has all the privileges of being an EU member state, which includes receiving large sums of EU money.

Public demonstration in front of the Hungarian Academy of Science building against the removal of the Academy Science Research Institute’s autonomy. Istvan Balogh/Shutterstock

The inexplicable failure by the EU to enforce its own standards is particularly troubling and helps to normalise this behaviour. Indeed, there are clear signs such repressive practices are spreading. Anti-human rights legislation, policy and practice that begins in one country is frequently copied in another. Anti-civil society legislation recently adopted in Hungary and Israel, for example, which aims to stop protests and minimise the number of organisations receiving funds from abroad, was previously adopted in Russia.

Repressive practices against universities are starting to spread in Europe. Earlier this year it was reported that the Ministry of Justice in Poland planned to sue a group of criminal law academics for their opinion on a new criminal law bill.

Academics in distress

The freedom of academics and university autonomy is not entirely without scrutiny. There are some excellent organisations, such as Scholars At Risk and the European University Association who actively monitor this sector. But, at an international level, university autonomy is rarely raised when governments’ human rights records are being examined. And there is no single organisation devoted to monitoring the range of issues identified in our recent report.

Without proper monitoring, universities, academics and students are even more vulnerable because there is little attention paid to these issues. And there is little pressure on governments not to undertake repressive measures at will.

Thousands demonstrate in central Budapest against higher education legislation seen as targeting the Central European University. Drone Media Studio/Shutterstock

A global monitoring framework is needed, underpinned by a clear definition of university autonomy. The UN and EU institutions also need to pay more attention to the dangers that such attacks on universities pose to democracy and human rights. A stronger line against governments who are acting in violation of existing standards should also be taken.

Universities should be autonomous in their operations and exercise self-governance. These institutions are crucial to the healthy functioning of democratic societies. Yet academic spaces are closing in countries around the world. This should be a concern for all. The time for action is now, before this trend becomes the new norm.

Kirsten Roberts Lyer is a Associate Professor of Practice, Acting Director Shattuck Centre, Central European University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

China’s Rich Tradition of Embroidering

Throughout human history, we’ve used pictures to express what words cannot or created whole languages out of symbolic representations to better express our emotions and thoughts. That’s nowhere more true than in Guizhou, China, where the Miao marry handicraft and art to recount their history, legends and traditions without a written language at all.

That art? Embroidery. The Miaos’ pictorial language isn’t drawn or scribed, it’s stitched. Miao women begin learning their ancient, traditional form of embroidery at age 7 Their mothers and sisters teach the girls not only the physical aspects of the craft but the symbols and style that preserve the stories of their people.

Animal imagery, like horses, snails, dragons, chickens and goats have meaning in narrative form that Miao women embroider into intricate garments. It takes years to complete one of these wearable histories, and the results are as beautiful as they are important for preserving a culture and history that doesn’t use written words.

The goal of all language is to communicate clearly and effectively to represent the shared experiences, thoughts and emotions we live and breathe as a species. The Miao certainly understand that like few other people as they proudly stitch and wear their language.