While following Jemima, a little curious girl who wanders through dusty roads, crowded markets, slaughterhouses, furnaces and bat hunters, we get acquainted with three women who describe the harsh realities of being born female and deaf in a society that discriminates against both women and people with disabilities. The stories of Immaculée, Sylvie and Stuka are stories of everyday struggle against marginalization, abuse, and oppression, but despite the insurmountable obstacles imposed on them by society, the protagonists show us how their strong and undefeated will allows them to take hold of their fate every single day and reveals the beautiful resilience of the human spirit.

I Was Called The N Word in The Philippines

It was only my second day in the Philippines and my Couchsurfing host invited me to watch a basketball game that he was playing in. Granted, the Philippines was a completely new country to me. I never thought that 2017 would bring me to Southeast Asia, but it has. In the Philippines, the heat makes you sweat relentlessly and you have to take numerous showers a day. Stray dogs and cats search for food in the streets, and trees are a beautiful invasion in the cities I’ve visited thus far. So much of it reminds me of my childhood visits to see family in Jamaica.

I head to the game around six pm and sit with my Couchsurfing host’s friend. It is only day two, but I’ve already become accustomed to one thing here. People stare at me. A lot. I know it’s because I’m black and traveling. The questions are always the same when I meet a new person here.

Do you play basketball? Do you know Lebron James? Is your father tall, just like you? Do you have a girlfriend?

Although traveling is about leaving your comfort zone, there is something to be said about how the identities that we are given in this world will affect us when abroad. I would never wish that I were white so that I could travel and feel more comfortable in this sense. I simply wish my representation in the media wasn’t controlled by people like who me and not white CEO’s.

The game starts and I notice little children gathering near me. They stare, whisper to one another and giggle before running away. After a few minutes, one little boy comes up to me and smiles.

“What’s your name?” he shouts.

I smile and tell him, “My name is Ryant. How old are you?”

He holds up seven fingers and then runs off. His friends greet him with an explosion of laughter. I am sure he will get the award for Bravest Boy in the Neighborhood later. Soon all of the kids are surrounding me, climbing onto my lap and asking questions. I’m invigorated by all of the energy, but I can’t help, but feel like a weird toy that one of them found and can’t wait to show off. More questions are fired off, an auction of how much information I can spit out. Then it happens.

“You’re a n----!”

My Couchsurfing host’s friend is sitting nearby and doesn’t bat any eyelash. On the outside, I nod awkwardly, but on the inside, I don’t quite know what to think. Since starting and graduating college, I’ve filled my mind with the words of many famous black freedom fighters. Angela Davis, a famous black activist born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1944 and who later faced an unfair trial for crimes she didn’t commit, wrote about the children she met while in Cuba:

Despite the language barrier, the children accepted us as members of the family. They helped me with my Spanish lessons each day. I was extremely embarrassed that I had not learned a little Spanish before the trip, for it is an affront to a people to visit them before having attempted to learn their language. Because I spoke Spanish so poorly, never having studied it, I felt less inhibited with the children. They were patient, corrected me and helped me find words when no dictionary was available.

It was a sad day indeed when we had to pack up our things and board the bus, ready to move on to the next stage of our journey. All of us cried — men and women alike, in our delegation as well as on the Cuban side. The hardest part for me was saying good-bye to the children. A young boy of about nine or ten, who had always been the toughest one of his group, seemed reluctant to come up and say good-bye. I thought that it was his natural shyness. Just before I got into the bus, I went over to him and gave him a kiss on the cheek. He tore away from me and ran as fast as he could. But once in the bus, I saw him standing behind a tree, trying to conceal himself as his body shook with sobs. The tears that had been flooding my own eyes slid down my face.

I think of her often when I can’t immediately find the words to respond to an ignorant comment from an acquaintance or when I need a push to live out my ideals for social justice. I’m looking at the faces of these cute Filipino kids and wondering how I can possibly unravel to them my life, my pain, and what it takes for a twenty two year old gay, Caribbean American boy to uproot his life and buy a one way ticket to Southeast Asia.

I realize it’s impossible.

“You shouldn’t say that word,” I tell them. “In the United States, it’s very bad.”

Immediately the kids start to frown and look at each other in confusion.

“Why?” the first boy who ran up to me asks.

I tell them the basics. In the United States, black and brown people have been treated badly for a long time. That word was used by white people to make people that look like me feel bad.

“Oh… That word means gangster fighter in Tagalog.” the kid replies.

I laugh as the coach in the game blows the whistle on a foul. The serious part of me doesn’t want to laugh, but I can’t help it. One problem leads to another of a different shade I suppose. I can’t break down racial stereotypes to a group of elementary aged children just yet.

“Teach me some Tagalog.” I request.

They all giggle and teach me phrases. When the game is over, they pull me onto the court and beg me to shoot a basket. Inside I’m rolling my eyes and wishing this wasn’t happening this way, but my heart is still melting. They run around me, teach me how to dribble and all jump in excitement when I shoot a basket after a million tries.

On my walk home, they all ask to add me on Facebook and I am laughing more. I’ve accepted that these moments may be a reality wherever I go, but acceptance does not mean I won’t struggle towards a more loving way of life. Travel opens the eyelids, pumps blood into the heart and fills the body with moments of awe. I felt that awe as those kids stared at me with their curious eyes and interacted with me so openly. I knew that I could strive to do the same in return and attempt to shed light on confusing, yet present truths as well.

Yes, I was called the n-word in the Philippines, but I do not define myself by the rules that society sets for a black person, a traveler, or 22 year old who is just trying make sense of a messy world. Instead, I keep going forward with conviction, sure that I’ll speak up whenever is necessary along the way.

RYANT TAYLOR

Ryant Taylor is a writer and activist from Cleveland, Ohio. He has participated in protests in France, Ferguson, and Standing Rock. He is the creator of Decolonize The Mind, a travel blog, and is currently freelance writing in the Philippines.

Explore Aotearoa with Ludovic Gilbert

Aotearoa is the Maori name for New Zealand. Ludovic Gilbert and his wife spent 3 weeks there for their honeymoon, and traveled more than 4,000 miles through Christchurch, Akaroa, Lake Tekapo, Te Anau, Wanaka, Fox Glacier, Punakaiki, Kaiteriteri, Wellington, Tongariro, Taupo, Whengamata and Auckland. Here are the fantastic landscapes, beautiful people and lakes with amazing colors they found.

Unravel: A documentary about the Kutch District of India

Clothing from Westerners who throw away their clothing often winds up in India. This video documentary visits the Kutch District in India, which is a major destination of used clothing. The clothing there is torn apart and turned into thread to create new garments. The community in the Kutch District is fascinated by their ideas about the Westerners who they imagine only wear their clothes a few times before throwing them away.

How to Find Authenticity in a Globalized World

Why do we travel?

For those of us privileged enough to be able to travel voluntarily, reasons often include becoming more fully ourselves and experiencing something genuinely different. This desire for authenticity, in ourselves and in that which we perceive to be other and outside our current experiences, is widespread enough to be noticed and exploited by the tourism industry, with signs reading “experience the REAL Thailand” and “find yourself in Bali”.

Seeking authenticity in our travels comes from a good place. It highlights our desires for genuine interactions with other human beings, for learning about the experiences of those with different life paths and identities, and possibly even for utilizing our privilege to support real people instead of opportunistic corporations removed from the locations in which they operate.

However, as is the case with many good intentions, this desire for authenticity can be harmful. Much of this harm stems from a strict and arbitrary idea of what counts as authentic and the fact that the privileged traveler has the power to decide what makes the cut. For instance, while spending 3 months in Zimbabwe a few years ago, I asked several friends what their cuisine had looked like prior to British colonization. As their current main foodstuff, a labor-intensive dry porridge called sadza that holds its shape when spooned onto a plate, is made of cornmeal, it couldn’t have existed prior to the transfer of corn to Africa from the Americas. I’ve had similar questions about Italian, British and South Asian cuisines before tomatoes, potatoes, and chili peppers made a similar journey. From my perspective, sadza was a colonial by-product, as was the black tea served alongside it. When I shared this view with my friends, the effect was clear: my strict and arbitrary definition of what could be considered authentically Zimbabwean delegitimized and minimized their identity and emotional ties to the food they knew and loved.

This highlights a tendency in our search for authenticity - to regard older traditions and cultural forms and those which predate recent cultural exchange as more authentic. This viewpoint is understandable, especially as a reaction against the infiltration of Western corporations such as Coca Cola into most crannies of the world, including a remote village in eastern Zimbabwe, and the Westernization of many popular tourist destinations, from food offerings to street signs. Yet the reality is that all places and peoples are dynamic. Historical and current globalization, the movement of people, ideas and things, has fostered cultural exchange and the transformation of traditions over time. Cultures also evolve without interaction with outside forces. When we define authenticity as similarity of a particular part of a culture to its version at a particular point in history, we mistakenly regard people and places as static, freezing them in time.

Aside from our tendency to award authentic status to more longstanding traditions, we also withhold this label unless the cultural form feels “other” enough and different enough from our cultural forms to be plausibly untainted by them. But ironically and cruelly, our globally dominant culture and associated language simultaneously demand conformity for material gain and social acceptance. Without this, the inherent amount of difference between cultures would render many practically inaccessible to travelers.

When we travel in search of authenticity with these unconscious assumptions and unfair expectations lurking in our minds, we often end up unknowingly demanding that locals perform a certain version of their culture for our tourist dollars. The result is a paradox: we want specific historical versions of cultures that are different enough from our own to feel authentic but similar enough to actually understand and enjoy. We travel to search for authenticity, but by traveling we reinforce the global dominance of our culture which demeans and degrades the other cultures we seek to experience. Seeking authenticity obscures it from us.

It also shortchanges us. Traveling with a particular idea of what authentic looks, tastes, smells and sounds like creates expectations and takes our attention away from what is. When we’re less present with ourselves, where we are, and the people around us, we’re less likely to feel deeply satisfied in addition to being more likely to cause accidental harm.

So, what to do? Here are some guidelines for navigating these realities:

1. Take people and places as they are now

Don’t force them to live up to some idea conjured up by tourist companies, history books, or your own mind as the antithesis to your everyday life. Don’t expect them to be similar enough to be accessible and understandable to you. On the flip side, don’t expect them to be different enough so that you can feel like you’ve escaped your daily grind and your culture. Manage your expectations or avoid forming them. Of course, it is very hard to travel with no inkling of what you’re going to find once you arrive, but be honest with yourself. Why are you drawn to particular places? What expectations do you have? Find balance - have just enough foresight to plan yet not enough to keep you from accepting what is when you’re there. The best days often come when you're not expecting them.

2. Only do what you actually want to do

Travel guides and guidance from friends are riddled with “must sees”. What if nothing on those lists strikes your fancy? I almost always skip museums when I travel. While you could argue that I’m missing out on important historical context, I would argue that I’ve never absorbed this information from museums even when I’ve forced myself to go to them. Luckily, each place and culture and even person is unfathomably complex and contains endless dimensions. Engage in the same activities you enjoy in back home and try new ones which feel right. Do you in a new place. By living your truth while traveling, you’re more likely to find authenticity in the place you’re visiting.

3. Engage other cultures carefully

Cultural exchange can be mutually beneficial but it can also be oppressive. Acknowledge the power dynamics in your interactions with non-travelers. Be aware that you probably embody and therefore unknowingly reinforce ideals that other people must conform to in order to gain social currency and acceptance. And make sure your engagement with other cultures doesn’t cross the line into appropriation. Appropriation can take many forms, but it almost always involves travelers benefiting materially from or being praised for a particular cultural form while the people to whom that cultural form belongs are ridiculed, persecuted, or exploited for it. Engage from a place of humility to learn, not to seek validation or make money. Always respect the stated boundaries of engagement, and where appropriate, wait to be invited.

SARAH LANG

Instigated by studies in Sustainable Development at the University of Edinburgh, Sarah has spent the majority of her adult life between 20+ countries. She is intrigued by the global infrastructure that produces inequality and many interlocking revolutionary solutions to the ills of the world as we know it. As a purposeful nomad on a journey to eradicate oppression in all its forms, she has worked alongside locals from Sweden to Zimbabwe. She is a lover of compassionate critique, aligning impacts with intentions, and flipping (your view of) the world upside down.

Travel Volunteerism: Airbnb to Offer Users a Way to Help Local Communities

After 8 years in business, travel accommodations company, Airbnb is expanding its platform and the services it offers by launching Airbnb Trips. Initially a peer-based home rental service, the company went on to partner with major travel brands like Delta and American Express for airline miles, points, and business tools for users. Now, Airbnb’s co-founder and CEO, Brian Chesky, is rolling out plans to do more than just provide customers with access to private lodging; he also wants to provide travelers with things to do once they reach their destination. During November’s Airbnb Open, a travel and hospitality festival held in Los Angeles, Chesky told the audience that planning a trip takes longer than the actual trip, and his company wants “to take the research project out” of travel.

On Airbnb’s updated app, users can now create an itinerary under “Trips” and book “Experiences”— activities that range from those of typical tourism to exclusive events and meet and greets. About 1 in 10 of these Experiences are allocated for “social impact experiences,” which airbnb.com describes as volunteerism and getting involved with a “cause you care about [where] 100% of what you pay goes directly to the organizations.” Some of these causes relate to social inclusion, mass incarceration, and animal rights, and activities include dance, gardening, feeding the poor and composing music. These Experiences will reportedly cost between $150-$250, and Airbnb has waived its commission for social impact experiences.

Chesky says that Experiences will be available in 12 destinations—Detroit, London, Paris, Nairobi, San Francisco, Havana, Cape Town, Florence, Miami, Seoul, Tokyo and Los Angeles. He also says the company will expand Experiences to 50 additional cities around the globe this year, with the ultimate goal of being able to provide Experiences in every Airbnb host location.

Experiences, Chesky says, are ways to immerse oneself into local communities and are a part of a “holistic travel experience.” Social impact experiences are identified on the app by a “social ribbon.” The site notes that participating in this type of social volunteerism allows travelers to “join with passionate locals” and “leave your mark on the community.” Social impact experiences are always hosted by charities and non-profit organizations. Chesky also says that Airbnb has a partnership with the Make-A-Wish Foundation—the charity for children with life threatening illnesses—and that Airbnb will be granting “a wish a day.” This will be done via donations, accommodations, and “transformational experiences” according to its website.

Brian Chesky, the founder of Airbnb.

Learn more at airbnb.com and on their YouTube channel for a look at Social Impact Experiences at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CwwMT05jqfU&feature=youtu.be

ALEXANDREA THORNTON

Alexandrea Thornton is a journalist and producer living in NY. A graduate of UC Berkeley and Columbia University, she splits her time between California and New York. She's an avid reader and is penning her first non-fiction book.

Fight Volunteer’s Guilt

There is a feeling that all volunteers can relate to: post-volunteering guilt. It’s that feeling of returning home after an amazing experience working abroad, only to wonder “did I do enough?”. Did you spend enough time with the kids you were teaching? Build enough homes? Vaccinate enough dogs? Play enough games of soccer? The list can go on and on.

My husband, John, and I are experts at realizing this guilt. We have worked abroad in three different countries.; Teaching English, providing childcare, building houses…you name it. We met while both teaching in Lima, Peru for an organization called Tarpuy Sonqo. (tarpuysonqo.org – check it out if you’re heading to South America). He worked for six months building three houses, and developing a full curriculum for the 4th grade students. I spent the following two months continuing his teaching work. Our hearts were completely invested in our efforts, and of course we fell in love with every baby, kid and adult that we met along the way. (Another feeling that every volunteer can understand.)

When we returned stateside and started dating, our conversations were consumed with when we could return back to our classrooms in Pachecutec, the largest slum outside of Lima. We worried how our students were doing, if the projects we’d started were continuing, and if the volunteers we’d trained were maintaining our high standards. But with full-time jobs, eventually buying a house and adopting dogs, it was becoming unrealistic to return to Lima for more than a week or two. That wasn’t long enough to make the impact we had in mind.

Instead – we decided to take the business we were already running, and use it as a tool to provide continued support to the causes close to our heart. My travel photography company – Kristen Emma Photography – quickly developed into a forever-fundraiser for international charities. Our new motto became “Capture the world to help the world”. We decided to give 25% of our sales back to charities local to where each of my photos were taken. Anything from South America was given back to Tarpuy Sonqo – and other photos donated to a select charity based on their continental location. Within a few months of art shows we were supporting teachers in Peru, dog adoptions in the UK (dogstrust.org.uk), prenatal medicine for women in India (villageclinic.org), AIDS research and meds in South Africa (aids.org.za), even penguin conservation through the Pew Charitable Trusts and my recent trip to Antarctica.

Not only were we thrilled to be helping our Peruvian students – but our clients were amazed! With the rise of charity companies, and the one-for-one model, people are always looking for products that give back to various causes. Adding the charitable aspect to our business model was good for the charities – but also good for our bottom line. That certainly wasn’t our goal, but it helped put food in our dogs’ mouths. :)

The lesson learned is that volunteers can use their guilt as motivation to keep helping. It’s not always possible to physically get back to their area of choice – but they can instead work to find methods of help in their everyday lives. Of course, not everyone has a business that they can use like we did – but there are other approaches to helping:

· Getting married? Set up a gofundme page for a charity, rather than asking for gifts. (John and I raised over $5000 for Tarpuy Sonqo. It built an entire park in the slums where we taught, and a jungle gym in a 2nd location. Exchange rates are always your friend. :)

· Birthday? Have your friends bring a non-perishable good instead of a present for you, and then donate it to the local food shelf. (You don’t really need another pair of earrings anyway.)

· Clean out your basement, sell what you don’t need on craigslist, and commit some of the proceeds to your volunteer location. (Those college books you’ve been holding onto could fund new books for your students in Kenya).

· Have friends who are looking to travel? Put them in touch with your volunteer coordinator. A lot of organizations will trade housing and food in exchange for a few hours of work per day. My company of choice is New Zealand-based International Volunteer HQ. They’ve got volunteer placements all around the world, and their credibility makes sure volunteers stay safe while having an incredible experience. Check them out at ivhq.org. They charge some fees, but its always cheaper than a hotel!

· Volunteer locally! There are an abundance of opportunities to help in your own neighborhood. If you speak another language, you can teach ELL classes at your community center. Any work you found abroad can definitely translate to your own community – teaching, childcare, food shelves, and homeless shelters.

In the short seven months since we developed our charitable mission, we’ve raised over $1500 for our partner charities. Although it may not sound like much, it’s $1500 more than they had before. We could have easily NOT raised any money, but what good would that do? Its important to remember that even just $10 raised is helpful to any of the thousands of organizations around the world.

KRISTEN MACAULEY

Kristen is a Minnesota-based photographer, specializing in fine art travel photography. She has lived in three different countries, and traveled to all seven continents through her photography endeavors. Her goal is to use photography to show similarities between cultures, regardless of their location. In order to give back to the communities that she photographs, 25% of all sales are donated back to local charities around the world. See her work on Etsy or on her website.

Conscious Capitalism: Meet Gingi Medina, Founder of Equites, An Equestrian Lifestyle Brand

Gingi Medina

There is a duality that radiates from clothing designer Gingi Medina. She is a determined, audacious business owner, who also cares deeply about the world, and minimizing waste. She struck out on her own, in part, because of the massive overproduction she saw in her industry. After a dozen years working in fashion, Gingi became disgusted by the excessive wastefulness in the manufacturing process, and thought there must be a better way to produce beautifully made garments, without littering the planet.

She began brainstorming ways to use materials that utilized the entire plant, animal, or raw substance. After years of making clothes, bags, and goods, Medina founded the lifestyle brand, Equites. The company, which is known for its leather, uses reclaimed and raw materials that are sourced ethically, she says.

In deciding to make leather goods, Medina argues that it's an emission-less process. Leather is a "conscious material" she says, because it's sturdy, durable, and long lasting. "It's a forever piece," she says. "If I make a bag out of leather, it has a far less, if any, carbon footprint left on the planet." Leather, Medina claims, does not require much processing because it utilizes a material that is taken directly from a natural source, versus a synthetic piece or garment-- including vegan leather-- which is manufactured and produced with emissions. She says her goods can last a consumer’s lifetime, so a buyer will need only one of her bags for example, rather than multiple synthetic bags that eventually wear out and need to be replaced. "The carbon footprint from a manmade item is far more extensive," Medina says.

The Weekender Bag, £800 [$1006 USD]

Medina didn't always know she'd be a conscientious designer. As a child growing up in Los Angeles, she imagined she'd be "an astronaut or the next Madonna." Magician also made the list of what Gingi thought she'd do one day. By the time she was 9 years old, she began calling herself "a designer." She recalls watching her first fashion show and thinking of predicting trends, sewing, and being able to say, "I made that." Ten years later those predictions began springing to life, and she entered the fashion realm as a fit model for petites. One day a designer asked her what she wanted to do, and she replied, "your job." That not so quiet confidence, that some have called "crazy", has served her well.

During her younger years, while partying in Hollywood, she says she encountered a well-dressed guy. Upon learning he was a designer, she offered to be his apprentice, working for free. Everyday for a year, beginning at 7am, Gingi set out to learn all she could about design. She learned how to construct leather, metal and denim. She made clothes for rock musicians, and clothing for tours-- most notably Ozzfest.

Medina’s work has also included her dressing celebs, working on TV shows, and ensuring certain designers' wares were featured prominently via product placement. She's worked as a buyer, and also in private label-- offering clothing styles to retailers who then put their own label on the garments. Medina has worked and studied fashion overseas. It was during her travels abroad and also mingling with and being inspired by people who've worked abroad, that she had some of her most successful innovations. She designed the Von Dutch "No More Landmines" tee-shirt after Angelina Jolie did mission work with the Halo Trust, which deactivates land mines in war ravaged regions. It was also during this time, that Medina began to reflect on the inefficiencies within fashion production and wondered, "Am I harming or helping... in my career." She remembers seeing freight containers filled with the previous fashion season's discarded garments and the subsequent feelings of what such wastefulness does to the planet. She noted that her clothes, and other finely made garments, were items consumers could have "for a lifetime", and even be "passed down", minimizing some of the waste. The ideas for change were within her, still she said it was, "hard to keep focus when the world is crumbling around you."

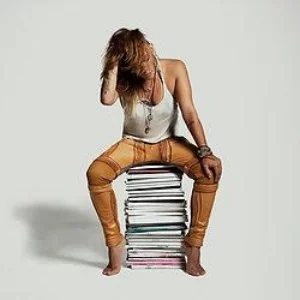

Leather Riders, £1800 [$2265 USD]

Ultimately, Median created her own brand, Equites, in 2011. She describes it as a "five tier label where performance meets fashion." Her line includes leather goods—pants, bags and jackets—but also cashmere, performance gear, and transition wear. She says her clothes serve as a "smart garment" that allows customers to segue "between worlds" and be just as comfortable and coiffed wearing riding pants, for instance, in an equestrian event as one would be at a premiere. Her line's leather pants, for example, are made of 17 panels sewed together on top of a water wicking, breathable legging, making it suitable for multi directional athletic endeavors and fitting to wear throughout the day.

When she initially showcased these designs, Gingi says her "idea was turned down by every label," so she produced them herself. Still committed to minimalism, and anti-waste, Gingi sought out hardware for use in buttons, and researched international communities that use the entire animal, and where she could also use their skins for her leather.

She found the Eid al-Adha, or the Festival/Feast of Sacrifice, in Indonesia. This global Muslim holiday commemorates Abraham's willingness to obey God, and sacrifice his son, who was ultimately spared, and a ram was sacrificed in his stead. During this multi-day festival, livestock—cows, goats, sheep, and camels, depending on the region—are sacrificed, and the meat, in part, is given to the poor. After the festival, some temples will sell the animal skins to Westerners, Medina says, which she considers ethical.

Gingi describes the “ethical use of a skin" as being "when the entire animal is used and not only sought out for its skin to make a product." Her company Equites, she says, searches "far and wide for leather or a fur that has already been used," to then "recycle or upcycle the piece into something new. [We] make sure we know where it's come from.” Medina asserts that she doesn't use slaughterhouse leathers, and does “not support, nor purchase from major manufacturing facilities,” but rather acquires her animal skins and materials in “smaller, traditional ways,” like from temples. The fabrics are naturally woven, she says, and there are no chemicals used in the dying process, which further eliminates waste.

Brass Capped Knee Height Riding Boots, £1000 [$1258 USD]

Once she gets the rawhide materials back to her factory, the leather is treated with natural ingredients like oils and rocks. Occasionally vegetable dyes are used, when a customer requests a special color. Much of her items are bespoke—made to order. Turnaround can take between 45-60 days, Gingi says. She says her method of manufacturing is less wasteful and more supportive of the planet. She claims there are no companies quite like hers. In an environment where most fashion lines are “being gluttonous and over-producing,” Gingi believes her company is “doing a better job.” Although she’s unfamiliar with any manufacturers creating clothes in the same manner and impact as she does, Medina welcomes competing brands. She wants to encourage companies to elevate their corporate responsibility.

Medina would also like to form an alliance across industries. Fashion is seen as a “status industry”, but Gingi also has a passion to “do right by the earth”, she says. Her warehouse is slated to use a Tesla Powerwall battery—which stores electricity and solar energy for later use—and she wants to partner with other companies that have a similar vision and commitment to the environment.

Medina’s company Equites is headquartered in London and the line will be available to the masses in Fall 2017. Her wares will be available in Harrods, Harvey Nichols, boutiques, country clubs, equestrian specific stores, and on her company’s website. During the company’s soft launch, Equites currently has jewelry and wearable art, bags, and boots available at equites.co.uk and on their Facebook page. The company is also offering an invitation to its show at London Fashion Week in September of 2017 to its first one hundred customers purchasing "diamond tier" levels of the selection pieces available pre-launch.

ALEXANDREA THORNTON

Alexandrea Thornton is a journalist and producer living in NY. A graduate of UC Berkeley and Columbia University, she splits her time between California and New York. She's an avid reader and is penning her first non-fiction book.

The Truth about Socialized Medicine around the World

In 2010, I moved to Australia from the United States and stopped in Thailand to go diving. While walking back to my hotel, I started to have trouble breathing. When it didn’t go away, I took myself and my chest pain to the emergency room. It was sparkling clean and almost empty; the young Thai doctor was thorough and gentle, and I walked away with an EKG, a chest X-ray, and a prescription for antibiotics. The total cost of my visit, for which I had to pay out of pocket due to not being a Thai citizen? About $40 USD.

There is a lot of misinformation passed around in the United States about socialized healthcare. You can wait a year without treatment. There are only two MRI machines in all of Canada. Nobody actually likes the system, or uses it. But the one thing most Americans never do is actually use universal health care. So I asked residents of multiple other countries to tell me what their experiences were like.

ISRAEL

Health care in Israel is universal and participation in a medical insurance plan is mandatory. All Israeli citizens are entitled to basic health care as a fundamental right.

Abby: “I never used the medical system for emergencies. Doctor’s offices seemed more like walk-in clinics than private practices, but Tel Aviv is very crowded. Even with an appointment, wait times were often 40-60 minutes.

I paid small co-pays, only to see specialists. Generally, the system was very low-cost and easy to use. I had to pay for prescriptions, but they were very cheap, especially compared to the States. A downside for me was that, while the doctors spoke perfect English, often the receptionists, nurses, and other office workers didn’t, so I had to get my Israeli boyfriend to make the appointments for me.”

ENGLAND

The NHS is the state healthcare provider in the UK. The service is free at the point of use; services are free, and running costs are covered by taxation. Private insurance is used by only 8% of the population of England.

Tim: “I have used the NHS many times, although, where possible, I go to private providers to save resources. Emergency work is almost always done on NHS. My mother was recently diagnosed with lung cancer and the NHS could not have moved faster; she also gets a choice of where she can be treated. She got a biopsy yesterday, the results ought to be back in five days and then treatment will start immediately. You would not receive any better with private insurance (and I say that as Tory).

Going to Emergency (A&E) is usually good, which I know from all my rugby injuries. You can get patched up and sent on your way in a reasonable amount of time. Getting a GP appointment (a general doctor, who will give you a referral), on the other hand, is almost impossible. The waiting time for my area is about three weeks. On the whole, the NHS is a good thing. It still has many flaws, though, and is in desperate need of a restructuring.”

AUSTRALIA

Australia has universal healthcare, called Medicare. It covers all general medical care, but some services are only partially covered and individuals pay a gap fee – this is usually still reasonably affordable, however. Individuals who earn high annual salaries are encouraged to take out private insurance.

Jenny: “I had an abnormal pap smear at my GP’s office, and she sent me a referral onwards to the Royal Women’s Hospital. I’ve had a lot of anxiety about pap smears in the past, and she specifically notified them about these issues. Since my issue was not urgent, she told me to expect a wait of several months for an appointment. The hospital recommended a colposcopy.

I contacted the patient advocacy department at the hospital and asked for assistance with my anxiety and PTSD. On the day of the procedure, all doctors and nurses were helpful and calming, and I managed to get through the experience without too much fear. They recommended that I get laser surgery to remove the abnormal cells from my cervix.

All of this has been totally free -- which is to say, paid for by Medicare. My original appointment for the pap smear was in May, and my laser surgery is scheduled for December...I received the appointment at the hospital in August. The abnormalities that showed in my report were not of an emergency nature; for similar issues, the brochure I received said patients can sometimes wait up to a year for treatment. I really appreciated the personalized care and support I received; it would have been so difficult to worry about payment while trying to deal with my emotional reactions to these procedures.”

FRANCE

All French residents pay compulsory health insurance, which is automatically deducted from paycheques. Patients pay fees at the doctor or dentist, which are then reimbursed 75-80% by the government, except in the case of long-term or expensive illnesses (such as cancer), which is reimbursed at 100%

Aliyah: “My father, who is Kenyan, was on a business trip in Paris. He tripped getting out of the subway and had a nasty gash above his eye. He was rushed to hospital, treated and held overnight for one or two days. When he was released, with medication, I kept bracing for the bill. None came. I told Dad to ask about it and he did. Answer: there is no bill, it is your right to be treated for free under our system.”

SWEDEN

The Swedish health care system is government-funded, although private health care also exists. The health care system in Sweden is financed primarily through taxes levied by county councils and municipalities.

Kelly: “Giving birth, tests, and one ultrasound were free. They charged me for extra ultrasounds and non-essential testing. The only thing they give you at the hospital for the baby is diapers, cream, and formula.

Generally, in Sweden, the health care works if you are dying or having an emergency. As long as everything's normal, no one will look twice at you or even WANT to see you more often than needed. The drop-in clinics (vårdcentral) never have enough staff or resources, so if you need to see a doctor, you exaggerate your symptoms or they just tell you not to bother coming in.

I have been struggling for 3 months to get a pediatrician for my daughter. Since I started trying, we went to the emergency room once, the nurse’s office 4 times, and I called the helpline a million times. No-one wants to actually see her.”

CANADA

Canada's health care system provides coverage to all Canadian residents. It is publicly funded and administered on a provincial or territorial basis, within guidelines set by the federal government.

“Everything is covered, whether it's something minor or surgery under anaesthetic. I've had MRIs, CT scans, x-rays, ultrasound, mammograms, you name it. The times I've had to go to emergency, I've received variable treatment, depending on the hospital. My longest wait was 13 hours. The shortest was ten minutes when I was afraid I had an aneurysm. For that one, I saw a specialist right away, which was also free. When my father had necrotizing fasciitis, he went to the hospital and was treated immediately. If he'd received treatment even 30 minutes later, he may very well have lost his leg or worse. In Canada, vision and dental are not covered by universal health care, and neither are things like physiotherapy, massage therapy, or alternative medicine like acupuncture, chiropractors, and so on. That being said, private medical insurance often covers a certain percentage of these things. Prescription medicine is also not covered by federal system, but between provincial plans and private insurance, can be greatly reduced in price if not free. Flu shots are free every autumn, and I remember getting vaccinated against rubella at school when I was a little kid. If you step on a rusty nail and go to emergency, your tetanus shot is free. Travel vaccinations and more unusual vaccinations, however, cost money. When I planned a trip to South America, I went to a travel clinic. The consultation was free, but I had to pay for my yellow fever and cholera vaccines.

I wish vision, dental, and physio were covered by national health care, but I am so grateful that everything else is covered. If they weren't, there's a chance I might not have survived as long as I have.”

IN SUMMARY

The United States is one of the only developed countries that doesn’t provide universal health care for its citizens. A friend of a friend had a baby at 28 weeks (extremely premature); the baby was in the NICU for several months. Fortunately, they had very good health insurance and ended up only having to pay $250 of the $850,000 bill -- but they were lucky. The United States healthcare system is a labyrinthine mess where insurance administrators make possibly lifesaving decisions about patient care, rather than doctors. The care you receive is based on what you can afford, not what you need.

Even with these astronomical costs to the consumer, the U.S. government still ends up paying more per capita for healthcare than countries with socialized medicine. Citizens of the U.S. have a life expectancy lower than other developed nations, and more elective surgery at higher costs...and paying more does not mean the service is better, as the U.S. also has fewer doctors than comparable countries. The systems elsewhere are not perfect, but the perfect is the enemy of the good: anything would be better than ending up in debt for the rest of one’s life, or worse, suffering (and dying) in silence because the cost of treatment is too high.

CLAIRE LITTON

Clair Litton was born in Canada, moved to the United States, went to graduate school in Australia, and recently relocated to Sweden. She has written for a series of online and offline magazine, and once had a young adult novel picked up by an agent, who then had to back down due to signing a little book called "Twilight." You can most commonly find Claire arguing about human sexuality and watching her toddler open and close doors.

5 Ways to Make a Positive Impact while Traveling in Bolivia

As one of the poorest countries in Latin America, Bolivia is a nation that, more than most, would benefit from your tourism. However, a historic lack of investment in infrastructure throughout the country and a reputation of political instability has left this nation neglected by foreign visitors.

Despite being more difficult to explore than neighboring Peru, Argentina or Brazil, Bolivia is a country that shouldn’t be missed. It has a wealth of diversity of natural landmarks, from the soaring Andes Mountains to the huge plains of salt flats to the Amazon jungle, as well as tiny communities inhabited by local, indigenous people ready to share their culture with curious travelers – and who really benefit from the income that responsible, considered tourism brings.

So here are 5 ways that you can do your bit to make a positive impact when you’re traveling in Bolivia.

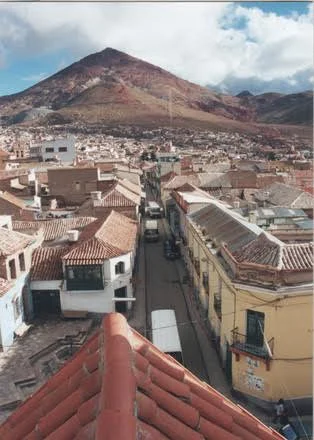

Potosi

1. Go Local

Many of us are more comfortable booking tours ahead of our trip to ensure that our visit runs smoothly and no time is wasted. But it can be difficult to know exactly how much of the money you’re paying is being invested into the country you’re visiting and whether the local people there are actually getting a fair deal.

Instead, booking tours when you arrive or online with locally-run, sustainable tourism agencies based in Bolivia will insure 100% of your money goes directly to the local people, meaning you’ll have a positive, responsible impact through your tourism.

Luckily, Bolivia has a growing number of excellent, responsible companies to choose from. Some of the best include:

Condor Trekkers based in Sucre is a hiking tour agency that leads treks into remote villages in the Andes, with hikes passing along stretches of preserved Inca trail and to landscapes potted with dinosaur footprints. They feed all of their profits back into the communities through which their tours pass to support locally-run, sustainable development projects.

The San Miguelito Conservation Ranch, a short distance from Santa Cruz, is a private reserve and conservation project that protects a section of wetlands acknowledged as having one of the highest concentration of jaguars in South America. This eco-tourism project runs tours to spot the big cats, birds and other wildlife in the reserve and uses the profits to maintain this important habitat.

Nick’s Adventures, another company based in Santa Cruz, runs a series of tours throughout the country, including spotting big cats in Kaa Iya National Park, the only park in South America established and administered by indigenous people. This agency supports sustainable development by providing employment to local people as drivers, guides and cooks and replaces any cattle killed by jaguars to stop ranch owners from shooting the cats, thus meaning that no jaguars or other native wildlife have been killed since Nick’s Adventures began this project.

La Paz on Foot runs walking tours in La Paz itself, as well as hiking trips further afield to indigenous communities. These communities receive much of the profits and La Paz on Foot have established a series of sustainable development and biodiversity conservation projects.

Solace Trekking Tours based in La Paz takes visitors on cultural tours to indigenous communities to take part in workshops about dancing, weaving and other traditional activities, as well as running climbing, biking and hiking trips to remote villages. Some of the profits of these tours are used to support the indigenous communities that are visited, as well as others who are fighting to save their land and water from mining – something that is a real threat to both natural habitats and the livelihoods of local people.

2. Don’t bargain too hard

Like many Andean countries in South America, artisanal goods of fluffy llama wool jumpers and delicate jewelry are hawked by locals on their stalls in every city and travelers are always keen to get a good bargain. But unlike parts of Asia and India where haggling hard is par for the course, in most of South America and particularly Bolivia, it’s not always the case.

Yes, you should expect prices to be higher for you; unfortunately, as a foreigner you will be charged an inflated rate. Negotiating a small reduction is sometimes possible, but most of the time, you shouldn’t try and push for prices that are vastly lower.

Shop around a bit and get a feel for what things cost, but follow your conscience with what you spend. Saving a few dollars on a jumper probably means very little to you in the long run, but in a country where 45% of people live in poverty and earn less than $2 a day, avoiding haggling sellers into the ground is the responsible thing to do.

3. Get off-the-beaten track

Most travelers in Bolivia stick to the main gringo triangle: La Paz, Sucre and Uyuni. And while these are certainly highlights of the country, other places also need the investment that tourism brings.

Towns such as Rurrenabaque, the best place in the country to access the Amazon Jungle, really need the support of responsible tourists. Once receiving lots of Israeli visitors (because of an Israeli who got lost in the jungle here a few decades ago and wrote a book about his experiences), numbers have dwindled since the Bolivian government decided to support Palestine and introduced a fee for Israelis entering the country.

Tourism is currently at a record low in the region and desperately needs travelers who are keen to visit. Check out sustainable operators, such as Mashaquipe Eco Tours, who charge fair prices and work responsibly to protect the jungle.

Another under visited location is Potosi. Here you can actually visit Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain), the famed mountain of silver that was plundered by the Spanish conquistadores.

Potosi is now the poorest city in the country and while many local people still attempt to make a living mining the last remaining minerals in the mountain, tours with ex-miners such as with Potochji tours, located in Calle Lanza, provide another option. Visitors can enter the mountain to see the terrifying conditions and ensure that their money supports ex-miners and the mining unions that now operate there.

4. Stay and volunteer

One of the most profound ways that you can help to support social development in Bolivia is by staying for a period of time to volunteer with grassroots projects. I’m always hesitant to volunteer for less than at least three months; I know that it takes time to learn about the organization and how best you can support its work.

In Bolivia, where few people speak English and where the culture is far more reserved than in a lot of other Latin American countries, it can definitely take time to start feeling like you’re making an impact.

Unfortunately, 90-day visas are the norm for most travelers arriving into the country, which can put a time limit on your volunteering. However, a visa of up to a year is not impossible to come by, but does require you to put a lot of effort into acquiring the necessary papers.

There are plenty of organizations that need your help, including Up Close Bolivia and Prosthetics for Bolivia in La Paz, Sustainable Bolivia in Cochabamba, Communidad Inti Wara Yassi in the Bolivian Amazon and Biblioworks and Inti Magazine in Sucre.

5. Or become an ambassador

But if you can’t commit to volunteering, how about becoming an ambassador or fundraiser for a charity based in Bolivia? While travelling in the country, take the opportunity to visit some of the many volunteering organizations to get an idea of what they do. When you’re back home, it’s easy to find a way to support their work.

You can become an ambassador who promotes the charity to their friends and social media followers, as well as signing up to make a regular donation. You could also volunteer long-distance by supporting fundraising efforts or helping with their social media accounts. Most importantly, you can spread the word about what they’re helping to achieve and find other volunteers or sponsors who can support their efforts.

Ultimately, Bolivia is a fascinating country to visit and so by traveling responsibly and considering how you can make a positive impact as a foreign tourist will support social development projects in increasing the quality of life for the Bolivian people.

STEPH DYSON

Steph is a literature graduate and former high school English teacher from the UK who left her classroom in July 2014 to become a full-time writer and volunteer. Passionate about education and how it can empower young people, she’s worked with various education NGOs and charities in South America.

Take Only Memories, Leave Nothing but Footprints

Photo credit: Waves for Water

Update from Waves for Water's Efforts Post-Hurricane Matthew in Haiti

Jon Rose, founder of the non-profit Waves for Water, sent CATALYST an update on recovery efforts in the wake of Hurricane Matthew.

It’s been just about two weeks since Hurricane Matthew made landfall on the South Western tip of Haiti. Two long, hard weeks for millions of people affected by this catastrophic event. In retrospect, I went into this one a little cocky, I think, mostly because I feel so comfortable in Haiti. It felt like no matter how bad it was going to be, it was happening in a place that feels like a second home. I thought the relief plan/action would also be easier because we have such a solid, extensive local network and team there. And I thought my own psychological capacity would be more balanced on this one because I had gone through it before, in the same country. I assumed a bunch of things…

Well, the universe sure has a way of humbling us. In other words, I was mistaken on just about everything.

By day two on the ground, our W4W country director, Fritz Pierre Louis, and I, sat shaking our heads in disbelief. We basically had to throw everything that we thought we knew or expected out the window – to start fresh, as if this was an entirely new country. It is a different beast entirely than the 2010 earthquake that leveled Port-au-Prince.

Why? Many reasons, but I’ll list a few:

Photo credit: Waves for W

1. Scope of Destruction -

Earthquakes have an epicenter – a narrower, more pinpointed area of impact. With hurricanes of this size the swath of destruction can cover hundreds of miles in all directions, leaving town after town after town leveled. The mountain villages see tornado-force winds (140 mph) with flash flooding that turns each valley into a violent river, destroying anything in its path. The coastal towns get the worst of it with those same tornado-force winds mixed with a 15-20 ft+ storm surge (aka tsunami). Basically a storm like Hurricane Matthew is like if a tsunami and a tornado got in a fight. The sheer scale of devastation, the widespread scope, has left many very experienced relief agencies (including us) with the very hard decision of where to start first.

2. Remote Area -

The majority of the Southwestern tip of Haiti is quite rural. Which means that most of the towns that got hit hardest are small and hard to get to on a normal day – windy coastal roads or mountainous dirt roads the only way in or out. This was before the storm. Now, most of those roads have been compromised, leaving relief capabilities at a bare minimum. For many of these places, supplies can really only be dropped by sea or air, which both tend to have limited payload capacity. This limits not only the speed with which supplies can come in, but the quantity. And with the massive amount of need, quantity is everything at the moment. Normally, relief initiatives will set up a solid distribution outpost in or around all the ground zero areas and then create a regular flow of supplies to feed those outposts (almost always by convoys of large trucks). This just isn’t possible for many of these places, and it won’t be for some time – bridges and roads are washed out, making them only passable via 4x4 vehicles that can traverse the riverbeds.

3. Base of Operations -

In any good, large-scale/long-term disaster relief initiative, a solid BOO (base of operations) is imperative. This is the place from which teams can do all their planning/staging. It is basically home, office, and everything in between for the duration of the initiative. It needs to be close to ground zero, but with enough breathing room to create a habitable environment. It can often be a scenario as simple/rugged as a camp with tents, or commandeering an old building, or in the best case there are hotels or private rentals available. But in all these cases, we find a way to ensure the teams are safe and have what they need to do their job – power, cell and internet service, food, water, etc. In this case, the only real option was in the city of Les Cayes, which got hit really damn hard itself. But there is an airstrip, it has some hotels still operating on generators, cell service is in and out, and there is water and food accessible. The problem is some of the hardest hit areas are 4-5 hrs drive on 4x4 roads, so the amount one team can do per day, staging from so far away, is incredibly limiting. Until some of the major infrastructural issues in that part of the country are restored (roads, power, etc), which will be months, it’s nearly impossible for relief teams to set up proper long-term operations in those hardest hit areas. The only exceptions are small, targeted teams that can travel lightly in 4x4’s because they don’t have bulky supplies, such as ours (we can carry 200 water filtration systems and 100 solar powered LED lanterns, in two 4x4 vehicles), or medical triage teams. We have seen some of the medical teams already posted up throughout the region, in whatever buildings are still standing. But those aren’t long term operations, as medical is mostly needed in this initial stage.

These are all things I’ve encountered (individually) before, over the many disasters we've worked. But it’s the combination of them all at once that is making this thing such a beast. The only other one I’ve seen with a magnitude like this was Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, which is still known as the largest storm ever recorded. If Haiyan is the largest, then Matthew was its equally evil twin brother, whose only difference is being a few seconds younger.

So, what does all this mean for W4W? After two weeks of traversing the whole Southwest, we now have a very accurate assessment of the hardest hit zones and a good plan to serve them. I shall note, unlike the majority of our other disaster relief initiatives, this one will include a few new categories of relief beyond our normal focus of access to clean water.

Despite all challenges, W4W has hit the ground running with an action plan that focuses on access to the following essentials:

1. Water -

Access to clean water will still be our main focus, with a targeted implementation strategy aimed almost entirely on cholera hotspots. There have been over 20 new (Matthew related) cases of cholera that have popped up and these numbers are expected to rise dramatically in the coming weeks. Clean water is kryptonite for waterborne diseases such as cholera, so the more we target the areas where it is starting to spread, the better chance we have of curbing the amount of cases popping up, and prevent new ones. We did a very similar program in 2011, when the first outbreak happened in the Artibonite department of Haiti. In partnership with UN’s CVR division, we implemented 4,000 water filtration kits, with a full WASH (water, sanitation, hygiene) education protocol/training, directly in two of the epicenters of the outbreak (Mirebalais and Saint Marc). Shortly thereafter, reported cases leveled out. The implementation strategy for our program this time will be very similar – we’ve identified five areas where confirmed cases have popped-up, or ones we feel are most susceptible to developing them. We will focus the majority of our water filter supply on these areas. We realize that so many places need access to clean water (even before the storm), but since we have limited resources and can’t help everyone, we feel that the best way for us to make the biggest impact is to target our efforts, by tackling the cholera issue head on.

2. Light -

One of the main things that we feel is being overlooked is lighting. The power is out in all of these areas and will be for months. This means that once the sun goes down it is pitch black. There are obvious reasons why this is a challenge, but one of the major issues is safety. Light = community, people gather around any light source when it’s dark. To put it bluntly, a good light source dramatically cuts down the scenario of young women being alone/vulnerable in whatever dark shelter they’re staying. Right now, some families are burning small fires, inside or near their makeshift shelters. Which brings up other safety concerns in terms of breathing in smoke in a confined space, not to mention the incredible discomfort from the added heat alone. It’s already extremely hot, even at night. All of these points, we’ve witnessed personally, and has now brought this topic to the forefront for us. We feel that it is imperative to add this facet to our Matthew Relief Initiative. The lights we are implementing are solar powered LED lanterns that also have a USB port to charge a cellphone, as well as a built in radio (one of the primary ways that rural communities get their news/information). As a last little added bonus, we’ve sourced the lights in-country – so by adding them into our program, we are also contributing to the local economy.

3. Cash for Work -

We are establishing small scale CFW (cash-for-work) programs, focused primarily on rubble/debris removal from, starting with roads and community centers. These types of programs are widely used in development and disaster initiatives around the world. In a disaster situation, it’s a good way to help spark the local economy and fill some of the gaps left from the vacuum that follows a catastrophe such as this. The bottom line – everything has been stripped from these folks (including their jobs) and they need money, so rather than just give straight hand-outs, it's best to employ them, as there is so much to be done and they want/need the work. It's an honest job for services rendered, just like many of them had before. Local residents are already rallying and working for free to help their communities as best they can, but that doesn't put food on the table at the end of the day. The whole thing is overwhelming for them, so something like this helps to restore at least a little normalcy.

Given the conclusions I’ve come to from the last two weeks on the ground and our vast experience in this field, I feel like we are well equipped to not only handle this, but to create a large-scale, long lasting, impact.

I will also note that even though these first two weeks were primarily focused around assessing the situation on the ground, we also started implementing of all three facets of the program. At this point, we've already distributed 500 water filtration systems and 300 solar lanterns in eight communities — Port Salut, Chardonnieres, Port-a-Piment, Coteaux, Les Cayes, Aquin, Jeremie, and Leogane. We've done this through some of our existing local networks and in collaboration with NGO partners such as (Les Cayes based) Hope for Haiti and local Rotary Club chapters. Lastly, in terms of our CFW (cash-for-work) initiative, we kicked things off with the clearing of rubble/debris on the main road in Chardonnieres.

As our programs gain more traction in the coming weeks/months, more updates from us will follow. Thanks to all of you who have supported and believed in this initiative so far… this stuff simply doesn’t happen without you.

Look out for updates from W4W on their website: www.wavesforwater.org

Jon Rose

Jon Rose is the founder and CEO of Waves for Water, a non-profit organization that helps bring clean water to areas that lack consistent access to it. W4W does this through its Clean Water Courier program, which is based on a Do-It-Yourself humanitarian model.

What You Need to Know About Water and Sanitation

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, or WASH, are issues that affect the health and wellbeing of every person in the world. Everyone needs clean water to drink. Everyone needs a safe place to pee and poop. And everyone needs to be able to clean themselves. For many people, WASH concerns are taken for granted and their combined impact on life isn’t always appreciated.

But for hundreds of millions of others, water, sanitation and hygiene are constant sources of stress and illness. The quality of water, sanitation and hygiene in a person’s life is directly correlated to poverty, as it is usually joined by lack of education, lack of opportunity and gender inequality.

What's the scope of the problem?

780 million people do not have regular access to clean water.

2.4 billion people, or 35% of the global population, do not have access to adequate sanitation.

Photo credit: Flickr - Gates Foundation

Inadequate sanitation generally means open defecation. When people defecate in the open without a proper waste management system, then the feces generally seeps into and contaminates water systems. Just standing in an open defecation zone can lead to disease, if, for instance, the person is barefoot and parasites are there.

The problem is concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southern Asia and Eastern Asia. The country with the most people lacking adequate WASH is India.

Girls are the hardest hit by lack of clean water and sanitation for a few reasons. When schools lack functional toilets or latrines, girls often drop out because of the stigma associated with periods. Also, when families don’t have enough water, girls are generally forced to travel hours to gather some, leaving little time for school. This lack of education then contributes to higher poverty rates for women.

What are the health risks?

There are a lot of health risks associated with inadequate WASH. Just imagine what it would be like if you were drinking contaminated water and everyone in your community defecated in the open.

801,000 kids under the age of 5 die each year because of diarrhea. 88% of these cases are traced to contaminated water and lack of sanitation.

More than a billion people are infected by parasites from contaminated water or open defecation. One of these parasites is called the Guinea Worm Disease, which consists of worms up to 1 meter in size that emerge from the body through blisters.

Photo credit: Flickr - Andrew Moore

The bacterial infection Trachoma generally comes from contaminated water and is a leading cause of blindness in the world.

Other common WASH-related diseases include Cholera, Typhoid and Dysentery.

And, again, step back to consider what life without clean water and adequate sanitation would be like. A lot of your time would be spent trying to get clean water and avoid sanitation problems in the first place. And the hours not revolving around these concerns would probably be reduced quality of life because of the many minor health problems associated with poor water quality. Ultimately, inadequate WASH leads to reduced quality of life all the time.

What's being done?

For every $1 USD invested in WASH programs, economies gain $5 to $46 USD. In the US, for instance, water infrastructure investments had a 23 to 1 return rate in the 20th century. When people aren’t always getting sick, they’re more productive and everyone benefits.

While the numbers are daunting, a lot is being done. And the economic benefits of WASH investments make the likelihood of future investments and future progress much higher.

Some investments are small-scale, others are large-scale. On the smaller side of the spectrum, investments can go toward water purification methods, community wells or sources of water and the construction of community latrines.

Photo credit: Michael Sheldrick

For instance, in a slum in Nairobi, Kenya, the government recently installed ATM-style water dispensers that provide clean water to the whole community.

Larger scale investments include piped household water connections and household toilets with adequate sewage systems or septic tanks.

An often overlooked aspect of WASH involves behavioral hygiene, and, more specifically, hand washing. Simply washing your hands with soap can reduce the risk of various diseases, including the number 1 killer of the world’s poorest children: pneumonia.

What progress has been made?

In 1990, 76% of the global population had access to safe drinking water and 54% had access to adequate sanitation facilities.

In 2015, even though the population had climbed by more than 2 billion people, 91% of people had access to safe drinking water and 68% had access to improved sanitation.

That means in 25 years, 2.6 billion people gained access to safe drinking water and 2.1 billion gained access to improved sanitation.

India is currently in the process of an unprecedented WASH investment program. At the 2014 Global Citizen Festival, Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed to end open defecation in the country and has since mobilized substantial resources with the help of The World Bank.

What role does Global Citizen play in all this?

Global Citizen puts pressure on world leaders to focus on and direct money to poverty solutions around the world. When it comes to WASH, global citizens have helped raise awareness of the various associated problems and motivate politicians to invest in specific programs.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GLOBAL CITIZEN

JOE MCCARTHY

Joe McCarthy is a Content Creator at Global Citizen. He believes apathy is the biggest threat to creating a more just world and tries his hardest to stay open-minded and curious. Living in New York keeps him aware of how interconnected our world is, how every action has ripples.

Photo credit: Lisa Forseth

Highlights from Mashable's Social Good Summit 2016

“It’s the spirit of innovation, of risk taking, of daring that we need now more than ever in the humanitarian world,” Ravi Gurumurthy of the International Rescue Committee said. Gurumurthy was one of many leaders to speak at Mashable’s Social Good Summit, where topics ranged from mental health to child marriage to social activism. The two day conference (mentioned in last week’s roundup) brought speakers from around the world to lead roughly 55 sessions.

All of the sessions can be viewed here, but let’s take a minute to look at five of the highlights:

01 | Vice President Joe Biden and His Renewed Fight Against Cancer

"Imagine, just imagine, what the world could look like in 2030 if we're smart and we work like hell." Vice President Joe Biden’s message on day two was one of optimism. His three-part plan aims to end cancer by the year 2030 and "accelerate progress toward prevention, treatment and a cure." He spoke confidently of modern technology and international cooperation finishing the fight against cancer. Watch his 45-minute session here. Source: Mashable

02 | Minister Mohammad Al Gergawi’s New Measure of Success

In the session “Future and Hope,” Kathy Calvin sat down with Mohammad Al Gergawi, United Arab Emirates Minister of Cabinet Affairs and the Future. His title might seem far fetched, but the UAE has been focused on modernizing their government positions. Al Gergawi’s position is joined by a Minister of Happiness, a Minister of Tolerance, and a Youth Minister. Together, they represent the UAE’s new defense in the fight against terrorism and extremism: happiness, technology, and hope.

03 | The Social Progress Imperative Releases the People’s Report Cards

In line with the summit’s mission, the Social Progress Imperative teamed up with Global Citizen to create a new way to “grade” world governments on their alignment with the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The People’s Report Cards is a way for citizens to hold their governments accountable to the promise they made one year ago. (See last week’s roundup and Impact 2030.) Currently the world’s overall grade is only a C+: something Social Progress Imperative aims to improve with the People’s Report Cards.

04 | Memory Banda’s Courage in Standing Up Against Child Marriage

Memory Banda’s cause holds a personal importance to her: at the age of 13 she was nearly married off to a man much older than her. Now she champions the end of child marriage around the world. During her short interview “Rise Up,” Banda shared just a little bit about the Girls Empowerment Newport, which helped pass a law in Malawi banning child marriage and protecting 4 million girls. But the fight isn’t over, and Banda encourages other countries to follow Malawi’s lead. Source: Mashable

05 | An important Conversation with Ertharin Cousin

Social Good Editor Matt Petronzio welcomed the Executive Director of the World Food Programme in his “A Conversation with Ertharin Cousin.” After presenting a short video showing refugees suffering from malnourishment in South Sudan, the two launched in a discussion of what the rest of the world can do to help. While the task might be daunting, Cousin admitted, WFP uses technology to make it easier for individuals to help. Their “Share the meal” app allows people to provide food for children in Zomba—and it only costs US $0.50 to feed a child for a day. With that app and other kinds of technology being used to fight hunger, Cousin is hopeful of achieving the no hunger goal by 2030.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON CONSCIOUS MAGAZINE

MICHALAH BELL

Michalah Bell is a writer for Conscious Magazine.

Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons - scdnr

VIDEO: Old Subway Cars and Planes Get a Second Chance Underwater as Thriving Ecosystems in the USA

We’ve have all heard the phrase, “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” but New York's Metropolitan Transit Authority has turned their trash into a marine treasure.

Over 2,500 retired New York City subway cars have been hauled out to the the deepest, coldest parts of the Atlantic ocean and thrown overboard one by one into the ocean using a hydraulic lift. But before you panic, it’s okay. It’s actually a good thing!

As these stripped carbon steel subway cars reach the darkest lows of the ocean floor they are warmly welcomed by their soon-to-be marine life inhabitants. Over time, the cars become part of the underwater ecosystem, creating an artificial reef system, providing surfaces for invertebrates to live on and shelter for fish playing hide and seek with their predators.

The Subway cars act as “luxury condominiums for [the] fish,” providing more surface area for food and marine life to grow and flourish.

Though the project ended in 2010 and no new cars have been taken to sea, the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control has reported a 400% increase in the amount of marine food available per square foot. While this particular project only ran for 10 years, the changes it sparked are self-sustaining and the benefits will last much longer than that.

Restoring the ocean’s reefs helps to restore balance to marine ecosystems that have been damaged by pollution, coral bleaching, and overfishing which can allow algae to overtake and smother reefs.

Oceans make up 97% the world’s water, produce half of its oxygen, provide food and livelihoods, and regulate climate. But we’re damaging reefs and polluting the water. It’s important that we work towards restoring our oceans and reefs to preserve marine life and return balance to the system.

The benefits of creating artificial reefs from retired subway cars are two-fold. Sinking these cars is a great way to recycle them, without sinking the MTA’s budget, and goes a long way toward restoring reefs.

It’s worked so well that Turkey just put a plane into the water in the hopes of creating a thriving artificial reef and capturing the attention of experienced divers.

Now don’t you wish you could get a little subway car or plane for your fishbowl?

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GLOBAL CITIZEN

ZAIMAH ABBAS

Zaimah Abbas is a social media associate at Global Citizen.

DANIELE SELBY

Daniele Selby is a freelance writer for Global Citizen. She is currently a Master's of International Affairs candidate focusing on human rights and humanitarian policy at Columbia's University's School of International and Public Affairs. She believes that education and equal provision of human rights will empower change.

Photo credit: ayzh

These $2 Birth Kits Could Save Millions of Lives

Around 830 women die every day because of childbirths that go wrong. For every woman who dies, 20 to 30 more women incur long-term health consequences.

99% of these health problems occur in the developing world. The vast majority could be avoided if basic resources were made available and skilled health providers were more common.

Oftentimes, women acquire fatal infections from unsanitary medical supplies or environments. Other leading causes of maternal mortality include excessive bleeding and hypertensive disorders.

Reducing maternal mortality rates requires more health professionals and improved health infrastructure.

Progress also requires cheap supplies such as soap, clean towels, sterile medical equipment, gloves and rudimentary medicine.

When Zubaida Bai explored this problem she realized that the latter part was, theoretically, an easy fix.

Her background is in product engineering with a focus on social enterprise. She first started to think about maternal mortality when she contracted an infection after giving birth to her son.

Had Bai lived in a country without an adequate health care system, the infection could have become far worse. Millions of women with similar infections do not receive proper care and regularly die.

Bai created an organization to address this injustice. She named it ayzh, an acronym for the initials of her family members’ names. Ayzh is pronounced “eyes,” to convey how the organization looks at the world from a different angle.

She designed a biodegradable clean birth kit called Janma that sells for $2 to $5 USD and contains, “a soft, blood-absorbent sheet that provides a clean surface for birth; medicinal soap for the birth attendant; disposable gloves; a sterile blade to cut the umbilical cord and a sterile clamp to secure it.”

Photo credit: ayzh

The kits are sold to nonprofits that focus on improving maternal health outcomes and to hospitals and health providers around the world.

In some instances, the kits are assembled in local communities, potentially creating an opportunity for employment and enterprise.

Azyh has so far sold more than 100,000 kits in more than 11 countries. After their initial use, the kits can even be used as purses.

They’re working on a newborn kit to accompany the birth kit that will include, “a clean receiving blanket, infant hat, antibiotic eye cream, umbilical cord medication and gauze to apply it, that will retail for less than $5.”

The organization aims to distribute millions of health kits around the world, potentially saving millions of lives.