A United Nations agency warns that malnutrition in Gaza risks the loss of an entire generation, highlighting the threat it poses to women’s healthcare.

Read MoreThe Influx of ‘Pisupo’: Food Colonialism in the South Pacific

Globalization has created an influx of unhealthy canned food in the South Pacific region, leading to a dependency on it and increasing health issues associated with an unhealthy diet.

The influx of canned food in the South Pacific has led to a variety of problems. Salvation Army USA West. CC BY 2.0.

The legacy of colonialism has a lasting impact on the island of the South Pacific. Many of those islands have been colonized by Western powers, and some of them are still under the control of foreign countries. Due to this, Western influences are still pervasive throughout the region.

One lasting legacy of Western imperialism in the South Pacific is the introduction of canned and processed food. The first canned food to be brought to the region was pea soup, and therefore, Samoan and a few other languages of the region, the word for canned food in general is “pisupo.” Today, the predominant type of canned food in the region is corned beef.

The prevalence of canned food in the South Pacific has changed the diets of the people living there and has caused a dependence on them. The new diets of the South Pacific Islanders are not necessarily an improvement from their traditional diets. However, as canned and processed foods are generally unhealthy and lacking in nutrients. That has resulted in an increase of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. Between 1990 and 2010, the total disability-adjusted life years lost to obesity also quadrupled in the region.

The traditional diets of South Pacific Islanders provide the nutrients needed for a healthy life. whl.travel. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

In order to provide these new foods, livestock such as cattle and pigs have been introduced to the islands, causing ecological damage. The island ecosystems are fragile, and large-scale ranching can easily destroy them. The dependence on canned food introduced by the West has resulted in not only harm to health, but also harm to the environment.

The proliferation of packaged and processed food has affected other parts of society as well, not just the typical diets. In marriage and birthday ceremonies in traditional South Pacific cultures, people often exchange gifts. While in the past, common gifts included fine mats and decorated barkcloths, but today, canned corned beef is one of the more popular gifts at those events. The introduction of canned foods has even changed traditional practices and contributed to the prevalent unhealthy diets of the South Pacific Islanders.

“Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000)” is a piece of art by Michael Tuffery that critiques the food dependency of the South Pacific. Sheep’R’Us. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The neocolonial nature of these developments has its critics. One of them, Michael Tuffery, offers a unique interpretation through his artwork, with one of the most notable being “Pisupo Lua Afe,” a sculpture of a bull made from canned corned beef. He says that his art addresses the impact that the “exploitation of the Pacific’s natural resources has wrought on the traditional Pacific lifestyle.” His choice of subject matter and the material show his thoughts on the influx of canned food in the South Pacific. Bulls were a common presence at the aforementioned ceremonies, and the fact that the bull is covered in canned corned beef represents the fact that more traditional practices. Tuffery laments the changes that globalization has brought to his traditional Samoan culture, which has led to a “decline of indigenous cooking skills.”

With so much waste being created in the making of “Pisupo Lua Afe,” Tuffery calls into question whether the physical and cultural costs of food dependence are worth it. Could the South Pacific do better without the influx of canned food? Tuffery argues that it could. But even if the South Pacific Islanders decide to shun the prevalence of canned food, hurdles remain to improve the health of both the land and people of the region.

Bryan Fok

Bryan is currently a History and Global Affairs major at the University of Notre Dame. He aims to apply the notion of Integral Human Development as a framework for analyzing global issues. He enjoys hiking and visiting national parks.

Why Explosive Population Growth Is Unsustainable

The world is experiencing massive population growth, most of it in the Global South. If nothing is done to slow the rate, repercussions will be felt in politics, the economy and the environment.

A crowded street in Nairobi, Kenya, which has one of the highest population growth rates in the world. rogiro. CC BY-NC 2.0.

The world’s population is growing at an alarming rate. In 1950, the world’s population was estimated to be around 2.6 billion. In 2022, it is almost 7.9 billion. While it is true that the world theoretically has enough resources to support the entire current global population with room to spare, the rate of population increase is a cause for concern. Most of the world’s resources are concentrated in the countries of North America and Europe, but most of the world’s population growth is located in the Global South, which can negatively affect the development of those countries.

When agricultural societies start to industrialize, the death rate usually drops due to advances in medical care. The birth rate stays high for a while until social changes encourage more women to join the workforce and have fewer children. Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa are stuck in a demographic transition trap.

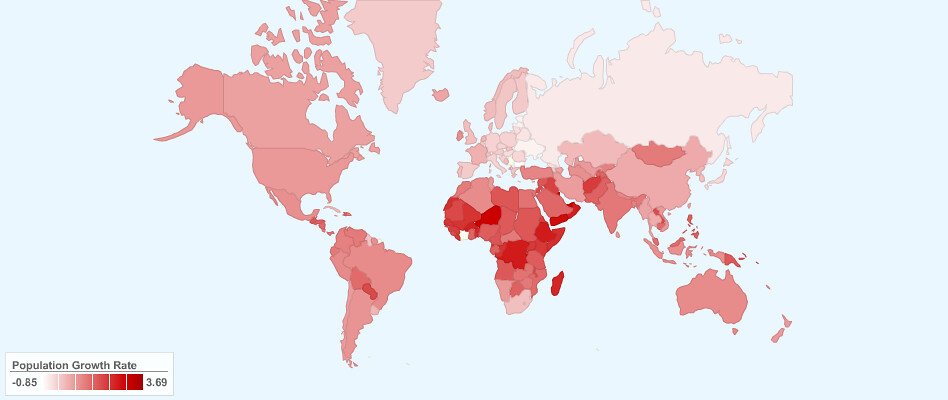

Current world population growth rate by country. Digital Dreams. CC BY 2.0.

As countries in the Global South start to industrialize, their death rates are falling, but their birth rates are not dropping to match the death rate, resulting in explosive population growth. This demographic trap occurs when “falling living standards reinforce the prevailing high fertility, which in turn reinforces the decline in living standards.” When developing countries do not make the necessary social changes to accompany industrialization, the birth rate stays high even as the economy transitions away from agriculture. These countries are slow to change their view on the ideal family size in light of emerging industrialization, and many are still engaged in labor intensive industries which reinforce the need for many children to provide free labor.

This explosive population growth has detrimental effects on both the developing country’s economy and environment. It leads to political instability, as the deluge of people overwhelm governments, causing states to fail. Governments likely cannot provide enough resources to the ever-growing population, trapping people in a cycle of poverty. Many families are impoverished due to using their resources for taking care of many children, perpetuating a cycle of poverty.

The inability for a government to provide for its population results in a failed state. Of the 20 top failing states defined by the Failed States Index, 15 of them are growing between 2 and 4 percent a year. In 14 of those states, 40% or more of the population are under the age of 15. Large families are the norm in failing states, with women having an average of six children.

Not only does excessive population growth lead to failed states and economic problems, but it also leads to environmental problems as well. As the Global South develops, more and more people there are becoming consumers of energy and resources, contributing to climate change. In Madagascar, population growth has “triggered massive deforestation and massive species extinction.” The current rate of population growth is unsustainable in the long run economically, politically and environmentally.

However, previous efforts to decrease the birth rate in the Global South has led to the dehumanization of many women. According to Columbia professor Dr. Matthew Connelly, Americans developed programs to “motivate medical workers to insert IUDs [intrauterine devices] in more women” in South Korea and Taiwan, causing “untold misery” as there were not enough clinics to deal with the possible side effects of those procedures. Puerto Rico became a “proving ground for both the birth control pill and state-supported sterilization” due to American policy despite pushback from religious authorities. These efforts deprive women of their agency to plan their own families.

Interventions to limit population growth must ensure that families, and specifically women, have agency over their bodies. Comprehensive sexual education is an option to enable people to understand the reasons behind the different methods to decrease birth rates. Families must be able to make an informed choice on their family size, and such sexual education is a popular idea to achieve that in a humane and dignified manner.

Bryan Fok

Bryan is currently a History and Global Affairs major at the University of Notre Dame. He aims to apply the notion of Integral Human Development as a framework for analyzing global issues. He enjoys hiking and visiting national parks.

What the Earth would look like if all the ice melted

We learned last year that many of the effects of climate change are irreversible. Sea levels have been rising at a greater rate year after year, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates they could rise by another meter or more by the end of this century.

The Refugee Crisis Is a Sign of a Planet in Trouble

We must shift the structures of society to ensure the Earth remains healthy and everyone has access to a decent livelihood.

The plight of immigrant families in the United States facing threat of deportation has provoked a massive compassionate response, with cities, churches, and colleges offering sanctuary and legal assistance to those under threat. It is an inspiring expression of our human response to others in need that evokes hope for the human future. At the same time, we need to take a deeper look at the source of the growing refugee crisis.

There is nothing new or exceptional about human migration. The earliest humans ventured out from Africa to populate the Earth. Jews migrated out of Egypt to escape oppression. The Irish migrated to the United States to escape the potato famine. Migrants in our time range from university graduates looking for career advancement in wealthy global corporations to those fleeing for their lives from armed conflicts in the Middle East or drug wars in Mexico and Central America. It is a complex and confusing picture.

There is one piece that stands out: A growing number of desperate people are fleeing violence and starvation.

I recall an apocryphal story of a man standing beside a river. Suddenly he notices a baby struggling in the downstream current. He immediately jumps into the river to rescue it. No sooner has he deposited the baby on the shore, than he sees another. The babies come faster and faster. He is so busy rescuing them that he fails to look upstream to see who is throwing them in.

According to a 2015 UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) report, 65.3 million people were forcibly displaced by conflict or persecution in 2015, the most since the aftermath of World War II. It is the highest percentage of the total world population since UNHCR began collecting data on displaced persons in 1951.

Of those currently displaced outside their countries of origin, Syrians make up the largest number, at 4.9 million. According to observers, this results from a combination of war funded by foreign governments and drought brought on by human-induced climate change. The relative importance of conflict and drought is unknown, because there is no official international category for environmental refugees.

The world community will be facing an ever-increasing stream of refugees.

Without a category for environmental refugees, we have no official estimate of their numbers, but leading scientists tell us the numbers are large and expected to grow rapidly in coming years. Senior military officers warn that food and water scarcity and extreme weather are accelerating instability in the Middle East and Africa and “could lead to a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions.” Major General Munir Muniruzzaman, former military advisor to the president of Bangladesh and now chair of the Global Military Advisory Council on Climate Change, notes that a one-meter sea level rise would flood 20 percent of his country and displace more than 30 million people.

Already, the warming of coastal waters due to accelerating climate change is driving a massive die-off of the world’s coral reefs, a major source of the world’s food supply. The World Wildlife Federation estimates the die-off threatens the livelihoods of a billion people who depend on fish for food and income. These same reefs protect coastal areas from storms and flooding. Their loss will add to the devastation of sea level rise.

All of these trends point to the tragic reality that the world community will be facing an ever-increasing stream of refugees that we must look upstream to resolve.

This all relates back to another ominous statistic. As a species, humans consume at a rate of 1.6 Earths. Yet we have only one Earth. As we poison our water supplies and render our lands infertile, ever larger areas of Earth’s surface become uninhabitable. And as people compete for the remaining resources, the social fabric disintegrates, and people turn against one another in violence.

The basic rules of nature present us with an epic species choice. We can learn to heal our Earth and shift the structures of society to assure that Earth remains healthy and everyone has access to a decent livelihood. Or we can watch the intensifying competition for Earth’s shrinking habitable spaces play out in a paroxysm of violence and suffering.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN YES MAGAZINE.

DAVID KORTEN

David Korten wrote this opinion piece for YES! Magazine as part of his series of biweekly columns on “A Living Earth Economy.” David is co-founder and board chair of YES! Magazine, president of the Living Economies Forum, a member of the Club of Rome, and the author of influential books, including When Corporations Rule the World and Change the Story, Change the Future: A Living Economy for a Living Earth. His work builds on lessons from the 21 years he and his wife, Fran, lived and worked in Africa, Asia, and Latin America on a quest to end global poverty. Follow him on Twitter @dkorten and on Facebook.

5 Lessons I Learned from Living with an Extreme Eco-Witch

In a rural town in the coast of Ecuador I had the pleasure of living with a woman. An eccentric woman. Some even said a witch. Witch or not she challenged me to challenge myself and my ecological standing. Here is what I learnt.

The walls of the Secret Garden were embedded with glass shards. Above the wall sat strategically placed barbed wire. The wall stood 10 ft. high communicating something along the lines of “I dare you to even try”. I pictured every shard of glass as a remnant of the woman behind it. Hidden for 8 years by high fences and rumors that she was a witch. From inside she watched the uninterrupted life outside of her icy fortress. A bird that once caged itself and has been trapped ever since.

The Secret Garden was not so aptly named. It was the largest house on the block by at least one whole story. The Secret Garden. I repeated it to myself. The irony tingled on my tongue. My partner Alex held my hand as we entered what was to be home for the next month.

Bucket Showers

We’ve been here a few days shy of a month and for the most part have caused this eccentric woman a drought. We’ve been showering with a one liter measuring jug. While the locals nearby go to a well, she collects rain water. The roof has pipes fringing the roof which collect in a tank. From there it is pumped upwards into a second tank and then she uses gravity for the last step. Water flows from the highest tank into the taps. She relays to me she’s only had running water for 6 months though she has been collecting rain water for much longer. It’s going to be the second time she calls the truck. She holds my glance as she says this, looking me up and down and reinforcing the message. “The second time!”.

All water is conserved here. There are two buckets in the sink. One for washing and one for rinsing. It works in a cycle. The washing water is thrown out over the garden and replaced by the rinse water. Furthermore any water that goes down the sink or in the shower is collected in another tank.

The water truck comes. She looks defeated. Her statements are witty and passive aggressive as though she knows I was using 2 liters of water for my bucket showers instead of one. In my defense it is the dry season.

Lesson 1: Be conscious of water usage. Water doesn’t just fall from the sky ya know.

Fishy Road Kill and Voodoo Dolls

There was something missing about the house and for the first few days we couldn’t figure it out… and then we went grocery shopping. This woman didn’t own a fridge. Overall, it was a good thing as it meant that all left overs were eaten rather than thrown to the back of the fridge. She tossed us a Styrofoam box filled with brown goo; “just buy ice… oh and give it a wash”. Our seafood, was always bought fresh. Every morning there are fisherman detangling their catch from nets with the patience and precision that only years of practice could bestow. We would wait until lunch to cook our spoils and because of this it always had a thick pasty consistency and fishy road kill flavor. Our broccoli, too, was always expired. I cursed firstly the heat and then the cooler which only offered half a day of solace from the tormenting sun.

But we were not the only ones. She keeps her homemade cat food in a neighbor’s fridge. Two out of three of her cats’ bellies sag so low they sweep the floor. From what I saw this was her favorite neighbor. The man in the blue house down the road. The family behind her think that she is a witch. A label she perpetuates by leaving voodoo dolls over their side of the fence. The family adjacent to her vacated when she told them that she came from a land of devils. A clever play on words for the Tasmanian Devil in Australia. “The locals here are a little superstitious”, she cackles.

Lesson 2: Buy fresh and eat fresh. More walks to the market isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

You Threw THAT away?

Need I say this woman recycled? She owned a series of garbage containers distinguishing intricacies in the material. She was working towards a plastic free home, a feat much more difficult than it sounds. In our room there was a list of rules, one of which was “no plastic bags”. Buying food, if caught without a bag became a game of smuggling. The fruit and vegetable trucks come every other day at random times. And when caught off guard, we would use plastic. As per request, after unpacking we would wash the plastic bags and hang them up to dry, to be reused. This was done in secret to try to avoid a punishing eye about bringing home more plastic bags. More often than not we would walk home with an assortment of items stacked awkwardly against our chest and were greeted with an approving smile or “what’s for dinner?”.

Lesson 3: Everything can be reused, recycled or up cycled.

SHIT!

“This is the bathroom”. Alex and I were getting the grand tour of her house. “It’s a composting toilet so you can throw your toilet paper inside the toilet” “ohhh” “ahhh”. For anyone else who has travelled through Latin America, you know this is kind of a big deal. All you do is chuck some sawdust in afterwards and let nature do its magic. Well, technically less magic from nature and more bugs digesting feces which is then shoveled to be used for compost in the garden. Ta-da! The garden gifted her back fruits, vegetables, herbs and an assortment of goodies she made into cleaning products, mosquito repellent, even gift wrapping.

Lesson 4: Literally, you can recycle anything.

Bliss Bombs

She told us that the government watches her because of her ‘bliss bombs’, a fruity protein ball of shredded coconut, almond meal chia seeds and dates. “If you google ‘bomb’, which I do because of ‘bliss bomb’ then the government puts you on a blacklist”. Once a chef and always an animal rights activist, I was amazed at what much she could make with just vegetables and a few grains. No gluten, no fats, no meat and “no fucking sugar” this was written on a whiteboard in the kitchen and repeated in all of her meals. Her chili sauce, a family recipe, was to die for and made an appearance in different restaurants in the town, in recycled Gatorade bottles she collected along the road.

Lesson 5: You are what you eat. Eat to reflect your ethics.

Admittedly, I’ve never been overly conscious of my waste more than the basic dabble in vegetarianism and using a recycle bin. But, since moving out I’ve seen little differences here and there in my dispositions towards conservation and sustainability in everyday activities. This eco-warrior/ witch/ woman taught me a lot.

JESS LEMIRE

Jess Lemire is a traveller, writer and social activist, sometimes simultaneously. I write about the things that I am passionate about and am passionate about what I write. I'm a cultural observer and linguist at heart.

I love good food and am a low key fruit juice enthusiast.

Regenerative Agriculture: our best shot at cooling the planet?

It’s getting hot out there. For a stretch of 16 months running through August 2016, new global temperature records were set every month.[1] Ice cover in the Arctic sea hit a new low this past summer, at 525,000 square miles less than normal.[2] And apparently we’re not doing much to stop it: according to Professor Kevin Anderson, one of Britain’s leading climate scientists, we’ve already blown our chances of keeping global warming below the “safe” threshold of 1.5 degrees.[3]

If we want to stay below the upper ceiling of 2 degrees, though, we still have a shot. But it’s going to take a monumental effort. Anderson and his colleagues estimate that in order to keep within this threshold, we need to start reducing emissions by a sobering 8-10% per year, from now until we reach “net zero” in 2050.[4] If that doesn’t sound difficult enough, here’s the clincher: efficiency improvements and clean energy technologies will only win us reductions of about 4% per year at most.

How to make up the difference is one of the biggest questions of the 21st century. There are a number of proposals out there. One is to capture the CO2 that pours out of our power stations, liquefy it, and store it in chambers deep under the ground. Another is to seed the oceans with iron to trigger huge algae blooms that will absorb CO2. Others take a different approach, such as putting giant mirrors in space to deflect some of the sun’s rays, or pumping aerosols into the stratosphere to create man-made clouds.

Unfortunately, in all of these cases either the risks are too dangerous, or we don’t have the technology yet.

This leaves us in a bit of a bind. But while engineers are scrambling to come up with grand geo-engineering schemes, they may be overlooking a simpler, less glamorous solution. It has to do with soil.

Soil is the second biggest reservoir of carbon on the planet, next to the oceans. It holds four times more carbon than all the plants and trees in the world. But human activity like deforestation and industrial farming – with its intensive ploughing, monoculture and heavy use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides – is ruining our soils at breakneck speed, killing the organic materials that they contain. Now 40% of agricultural soil is classed as “degraded” or “seriously degraded”. In fact, industrial farming has so damaged our soils that a third of the world’s farmland has been destroyed in the past four decades.[5]

As our soils degrade, they are losing their ability to hold carbon, releasing enormous plumes of CO2 into the atmosphere.

There is, however, a solution. Scientists and farmers around the world are pointing out that we can regenerate degraded soils by switching from intensive industrial farming to more ecological methods – not just organic fertiliser, but also no-tillage, composting, and crop rotation. Here’s the brilliant part: as the soils recover, they not only regain their capacity to hold CO2, they begin to actively pull additional CO2 out of the atmosphere.

The science on this is quite exciting. A study published recently by the US National Academy of Sciences claims that regenerative farming can sequester 3% of our global carbon emissions.[6] An article in Science suggests it could be up to 15%.[7] And new research from the Rodale Institute in Pennsylvania, although not yet peer-reviewed, says sequestration rates could be as high as 40%.[8] The same report argues that if we apply regenerative techniques to the world’s pastureland as well, we could capture more than 100% of global emissions. In other words, regenerative farming may be our best shot at actually cooling the planet.

Yet despite having the evidence on their side, proponents of regenerative farming – like the international farmers’ association La Via Campesina – are fighting an uphill battle. The multinational corporations that run the industrial food system seem to be dead set against it because it threatens their monopoly power – power that relies on seeds linked to patented chemical fertilisers and pesticides. They are well aware that their methods are causing climate change, but they insist that it’s a necessary evil: if we want to feed the world’s growing population, we don’t have a choice – it’s the only way to secure high yields.

Scientists are calling their bluff. First of all, feeding the world isn’t about higher yields; it’s about fairer distribution. We already grow enough food for 10 billion people.[9] In any case, it can be argued that regenerative farming actually increases crop yields over the long term by enhancing soil fertility and improving resilience against drought and flooding. So as climate change makes farming more difficult, this may be our best bet for food security, too.

The battle here is not just between two different methods. It is between two different ways of relating to the land: one that sees the soil as an object from which profit must be extracted at all costs, and one that recognizes the interdependence of living systems and honours the principles of balance and harmony.

Ultimately, this is about more than just soil. It is about something much larger. As Pope Francis put it in his much-celebrated encyclical, our present ecological crisis is the sign of a cultural pathology. “We have come to see ourselves as the lords and masters of the Earth, entitled to plunder her at will. The sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life are symptoms that reflect the violence present in our hearts. We have forgotten that we ourselves are dust of the Earth; that we breathe her air and receive life from her waters.”

Maybe our engineers are missing the point. The problem with geo-engineering is that it proceeds from the very same logic that got us into this mess in the first place: one that treats the land as something to be subdued, dominated and consumed. But the solution to climate change won’t be found in the latest schemes to bend our living planet to the will of man. Perhaps instead it lies in something much more down to earth – an ethic of care and healing, starting with the soils on which our existence depends.

Of course, regenerative farming doesn’t offer a permanent solution to the climate crisis; soils can only hold a finite amount of carbon. We still need to get off fossil fuels, and – most importantly – we have to kick our obsession with endless exponential growth and downsize our material economy to bring it back in tune with ecological cycles. But it might buy us some time to get our act together.

[1] “August 2016 Global Temperatures Set 16th Straight Monthly Record”, weather.com, Sept. 20, 2016.

[2] “Arctic sea ice crashes to record low for June”, The Guardian, July 7, 2016.

[3] “Going beyond ‘dangerous’ climate change”, London School of Economics lecture, Feb 4, 2016.

[4] Anderson, Kevin, “Avoiding dangerous climate change demands de-growth strategies from wealthier nations”, Nov. 25, 2013.

[5] “Earth has lost 1/3 of arable land in last 40 years”, The Guardian, Dec. 2, 2015.

[6] Gattinger, Andreas, et al, “Enhanced topsoil carbon stocks under organic farming”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, vol. 109 no. 44.

[7] Lal, R., “Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Climate Change and Food Security”, Science magazine, June 11, 2004.

[8] Rodale Institute, “Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Climate Change”, April 17, 2014.

[9] Altieri, Miguel et al, “We Already Grow Enough Food for 10 Billion People … and Still Can’t End Hunger”, Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, July, 2012.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON LOCAL FUTURES.

JASON HICKEL

Jason Hickel is an anthropologist at the London School of Economics. He specializes in globalization, finance, democracy, violence, and ritual, and is the author of "Democracy as Death: The Moral Order of Anti-Liberal Politics in South Africa".

Kicking the Habit: Air Travel in the Time of Climate Change

Air travel is neither just nor sustainable. So how can environmental justice activists make a global difference?

We live in a time of far-flung relationships, our families, colleagues, and friends often spread out across continents. These relationships mirror the global nature of many of our most pressing problems, such as global climate change—and they also contribute to those problems.

In Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough Planet, Bill McKibben likens the biosphere to “a guy who smoked for forty years and then he had a stroke. He doesn’t smoke anymore, but the left side of his body doesn’t work either.” This new world, he says, requires new habits.

And, no doubt, many of us have adopted new habits—trying to use public transportation, buying local foods, rejecting bottled water. But the “savings” from such practices are wiped out by a habit that many of us not only refuse to kick, but also increasingly embrace: flying, the single most ecologically costly act of individual consumption.

Flights of Privilege

A round-trip flight between New York and Los Angeles on a typical commercial jet yields an estimated 715 kilos of CO2 per economy class passenger, according to the International Civil Aviation Organization.

Only 2-3 percent of the world’s population flies internationally each year, but the climate impacts are felt by a much larger—and poorer—population.

But due to the height at which planes fly, combined with the mixture of gases and particles they emit, conventional air travel has an impact on the global climate that’s approximately 2.7 times worse than its carbon emissions alone, says the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. As a result, that roundtrip flight’s “climatic forcing” is really 1,917 kilos, or almost two tons, of emissions—more than nine times the annual emissions of an average denizen of Haiti (as per U.S. Department of Energy figures).

Only 2-3 percent of the world’s population flies internationally on an annual basis, but the climate impacts of air travel are felt by a much larger—and poorer—population. It is difficult to illustrate the meaning of such numbers in terms of who among the planet’s citizens pays the costs.

But this is exactly what the 2009 German short film The Bill does in powerfully demonstrating the ecological privilege and disadvantage embodied by flying. In doing so, it shows aviation to be a classic example of how the comparatively well-off privatize benefits of environmental resource consumption (the ability to travel quickly and afar) while socializing the detriments. By making a disproportionate contribution to climate destabilization and associated forms of environmental degradation—biodiversity loss, rising sea levels, and desertification, for instance—air travelers exacerbate the precarious existence of the most vulnerable. In doing so, they contribute to unjust hierarchies (e.g. racism and imperialism) that reflect a world of profound inequality.

Global Organizing—Without Planes

Clearly this presents a huge challenge to social and environmental justice advocates, activists, and organizers from the planet’s relatively wealthy areas who often connect to distant peoples and places by flying. Because the institutions and individuals most responsible for our global predicaments typically exercise mobility and exert their power across great distances, those of us who want to challenge their practices often must also do so. So what to do?

One option is to use transportation that stays on the Earth’s surface, to accept traveling more slowly, and to make flying a very rare exception instead of the rule. Throughout North America, buses—and, in many places, trains—are viable options. And for transoceanic voyages, ships (including freight ones) are a possibility—albeit not typically inexpensive or as common as they need be.

In an increasingly vulnerable world, we’re searching for rooted communities—and what we can learn from them.

Another option—indeed an obligation in a time of growing ecological destruction and a degraded resource base—is to stay home more often. Given that “jet travel can’t be our salvation in an age of climate shock and dwindling oil,” McKibben writes, “the kind of trip you can take with a click of a mouse will have to substitute.” In other words, we have to become much better at exploiting the “trips” that the Internet and related technologies afford—by videoconferencing, for example.

While such options present numerous challenges, not least logistical ones, perhaps the biggest obstacle is the particular way of seeing and being common to the small slice of the world’s population that flies regularly. Traveling long distances by bus, train, or ship, for example, necessitates time—and a willingness to expend it in manners that those from the world’s privileged parts and sectors are not used to doing. It doesn’t necessarily entail doing less, but it does mean doing things in different ways.

A New Normal

It also calls for new mechanisms and institutions—and some organizing to bring them about. Take long-distance travel by ship. Less than a century ago, many regular folks traversed the seas—think of immigrants to Angel and Ellis islands. And many well-known organizers and activists—Gandhi, Helen Keller, and W.E.B. Dubois, to name just three—journeyed extensively by ship.

To do so today, of course, is far more difficult as jet travel has greatly weakened the passenger ship option. But what if, for instance, U.S. and Canadian activists and advocates going to Denmark for the Dec. 2009 climate summit had, instead of booking individual flights, organized to travel together by ship—with all promising to get to and from their ports of call by surface-level transportation? And what if they had publicized this effort as a way of setting an example for, and challenging, others?

That such a suggestion will seem unrealistic, if not foolhardy, to many illustrates the way that what we’re used to thinking of as normal can stifle our imaginations, and let us off the political, ecological, and ethical hook. The option is as “realistic” as we make it. In this regard, we need to push and support one another in the effort to make far-reaching alternatives viable.

What we’re used to thinking of as normal can stifle our imaginations, and let us off the political, ecological, and ethical hook. The option is as "realistic" as we make it.

Climate science tells us that we need a 90 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades to keep within a safe upper limit of atmospheric carbon. In light of the great changes such a reduction demands, what is unrealistic and foolhardy is the notion that we can continue flying with abandon.

Interested?

• We thought we had 20, 30, 50 years to take on the climate crisis. We were wrong. The scary science, smart policies, and critical actions that could still avert disaster.

• Bill McKibben imagines himself in the year 2100, looking back at a century of climate chaos and asking: What did it take to save the world?

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON YES MAGAZINE.

JOSEPH NEVINS

Joseph Nevins wrote this article for YES! Magazine, a national, nonprofit media organization that fuses powerful ideas with practical actions. Joseph is a geography professor at Vassar College. Among his books is Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid (City Lights Books/Open Media).

Less than Two Gallons a Day in Ethiopia

In rural Ethiopia, water is so scarce that many families survive on less than two gallons per day and walk up to four hours to find it.

Their water sources, often nearly-dry river beds or muddy holes that communities have dug together, offer water that sometimes needs to be poured through cloth to filter out leeches and debris.

Since 2007 charity: water has been working in the Tigray region of Ethiopia with the government and local water partners working towards a vision of 100% clean water coverage.

With the help of hundreds of thousands of supporters from around the world — like Noah, who taught his classmates how to weave and sold enough hand-made art to fund hand-dug wells — we’ve now funded more than 3,000 water projects in Tigray that will serve over 1.1 million people with clean and safe water near their homes. Not only that, but the community has also been trained by our local partners on safe hygiene practices and basic maintenance of their water project.

Take yourself on the charity: water journey into the heart of Ethiopia in this video series following our Content Strategist, Tyler, as he experiences life without water and meets the incredible people of Ethiopia.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA.

Photo credit: ayzh

These $2 Birth Kits Could Save Millions of Lives

Around 830 women die every day because of childbirths that go wrong. For every woman who dies, 20 to 30 more women incur long-term health consequences.

99% of these health problems occur in the developing world. The vast majority could be avoided if basic resources were made available and skilled health providers were more common.

Oftentimes, women acquire fatal infections from unsanitary medical supplies or environments. Other leading causes of maternal mortality include excessive bleeding and hypertensive disorders.

Reducing maternal mortality rates requires more health professionals and improved health infrastructure.

Progress also requires cheap supplies such as soap, clean towels, sterile medical equipment, gloves and rudimentary medicine.

When Zubaida Bai explored this problem she realized that the latter part was, theoretically, an easy fix.

Her background is in product engineering with a focus on social enterprise. She first started to think about maternal mortality when she contracted an infection after giving birth to her son.

Had Bai lived in a country without an adequate health care system, the infection could have become far worse. Millions of women with similar infections do not receive proper care and regularly die.

Bai created an organization to address this injustice. She named it ayzh, an acronym for the initials of her family members’ names. Ayzh is pronounced “eyes,” to convey how the organization looks at the world from a different angle.

She designed a biodegradable clean birth kit called Janma that sells for $2 to $5 USD and contains, “a soft, blood-absorbent sheet that provides a clean surface for birth; medicinal soap for the birth attendant; disposable gloves; a sterile blade to cut the umbilical cord and a sterile clamp to secure it.”

Photo credit: ayzh

The kits are sold to nonprofits that focus on improving maternal health outcomes and to hospitals and health providers around the world.

In some instances, the kits are assembled in local communities, potentially creating an opportunity for employment and enterprise.

Azyh has so far sold more than 100,000 kits in more than 11 countries. After their initial use, the kits can even be used as purses.

They’re working on a newborn kit to accompany the birth kit that will include, “a clean receiving blanket, infant hat, antibiotic eye cream, umbilical cord medication and gauze to apply it, that will retail for less than $5.”

The organization aims to distribute millions of health kits around the world, potentially saving millions of lives.

Large-scale investments in infrastructure and the training of medical professionals are obviously still needed and will have a much larger role to play in reducing maternal mortality. In the short term, with millions of women giving birth in unsafe environments every year, it may take entrepreneurs like Bai to save people through the simplest of innovations like an affordable birth kit.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GLOBAL CITIZEN

JOE MCCARTHY

Joe McCarthy is a Content Creator at Global Citizen. He believes apathy is the biggest threat to creating a more just world and tries his hardest to stay open-minded and curious. Living in New York keeps him aware of how interconnected our world is, how every action has ripples.

Pictures of Afghan children at a school run by a local mosque for Afghan orphans & refugees in Shiraz, Iran. Photo by Simon Monk (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

IRAN: A Commitment to Provide Universal Public Healthcare to Refugees

In an announcement from the United Nation mission in Iran, the Iranian government will include all of its registered refugees into its Salamat Insurance Scheme. This is a collaboration between the Ministry of Interior, responsible for immigrant affairs, the Iranian Health Insurance Organization and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This plan is targeted at Iran's Afghan and Iraqi refugee population.

Iran's English daily Tehran Times, part of the Mehr News Agency owned by the Islamic Ideology Dissemination Organisation, described the “gratitude” of Sivanka Dhanapala, the UNHCR Representative in Iran, for the program:

“UNHCR’s Representative in Iran acknowledged the Iranian Government’s contribution, expressed UNHCR’s gratitude towards the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran for all the services it has rendered to the largest protracted urban refugee population in the world for over three decades, and inclusion of the refugees in this Universal Insurance Scheme which is exemplary not only regionally but also globally, and added that such a services haven’t been provided before and I sincerely hope other countries will follow this example.

”

Half of the coverage for the program will come from the Iranian government, while the UNHCR will contribute with US $8.3 million. The program will be available to all registered refugees, who will receive access to a health insurance package for “hospitalization and temporary hospitalization”, as available to Iranian nationals.

According to the UNHCR website, Iran is home to one of “the world's largest and most protracted refugee populations.” Iran's Afghan refugee population nears 1 million, with an additional estimated 1.4 to 2 million unregistered refugees living and working in the country.

Iran's treatment of this demographic has been subject to past criticism, however, most notable in the 2013 Human Rights Watch report that detailed the mistreatment and sometimes abuse Afghans faced from both Iranian society and the government.

For their 2015 projection, the UNHCR detailed their expectations for Iran's intake for mostly Afghan, Iraqi and Pakistani refugees as outlined in the image below.

Iran has been criticized for not taking in any Syrian refugees throughout the civil war there. This reproach comes amidst the fact that it is heavily involved in the Syrian conflict as an ally and supporter of the Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad.

Indeed, this development in instating universal public healthcare for refugee populations is a notable milestone for both Iran and the region. Iran can, however, still improve its image in bolstering its role in alleviating the neighbouring Syrian refugee crisis.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GLOBALVOICES

Mahsa Alimardani

Mahsa Alimardani is an Iranian-Canadian Internet researcher. Her focus in on the intersection of technology and human rights, especially as it pertains to freedom of expression and access to information inside Iran. She holds an Honours Bachelor in Political Science from the University of Toronto and is completing her Masters degree in New Media and Digital Culture at the University of Amsterdam.

USA: The Lineage Project Brings Peace to Incarcerated and At-Risk Youth

The Lineage Project has its roots in San Francisco, when Soren Gordhamer and Andrew Getz, took their meditation into the juvenile halls in 1997. The idea hit the east coast when Gordhamer moved to New York City and brought the practice with him, starting the Lineage Project East in 1999. Now, more than a decade later, his weekly hour-long classes have helped hundreds of adolescents control their emotions, relieve stress, and bring awareness to their mental state of mind through yoga and meditation.

CONNECT WITH THE LINEAGE PROJECT

TANZANIA: Give Your Love Away

Healthcare is neither easily accessible nor affordable for many Tanzanians living in rural villages and poor urban areas. Anika Jeppesen traveled to Arusha, Tanzania to work as a medical volunteer through International Volunteer HQ’s medical placement program. Here is her experience.

LEARN MORE AT VOLUNTEER HQ

Strictly Beza: Combating HIV Through Dance in Ethiopia

In a country where more than half of the younger population was born during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Ethiopia is in dire need of education for its youth on practicing safe sex. To address this issue, a young dance troupe by the name of Addis Beza are utilizing their talents and passion for music and dance to educate community members about HIV prevention. During their public performances, the 15-20 member crew hands out informational pamphlets about HIV and encourages their spectators to get tested.

CONNECT WITH ADDIS BEZA