My Grandpa Joe was one of those classically great men. A mensch. Born in the bathroom of his parents’ Temple Street home in downtown Los Angeles in 1917. The family moved around Los Angeles a lot — from downtown to Boyle Heights to Tujunga to Beverlywood. Sticking close to the pockets of other Jewish immigrants who faced daily anti-semitism. In his pre-teen days, he would travel miles by bus to get to school, then travel all the way back to work in his father’s garment factory into the night — the schmata business — learning the machines. Then he’d do his homework. It was clear very early on that he was a standout student and, after skipping pretty much every other grade, he ended up at Berkeley. Apparently, he was in a rush to meet my grandmother, Ethel, who was also at Berkeley. After graduation, they came back to L.A. He also ended up in the garment industry, one of the first to create women’s sporting apparel.

And as great and respect-worthy as that all is, the story of how he made his way in the world was simply a precursor to a just-as-impressive story of how he made his way around the world. Joe’s true passion was travel.

By his retirement, he had also started a small side business as a travel agent. He called it, Love To Travel. He kept himself busy (and his travel deductible) by organizing and sometimes leading tour group in various parts of the world.

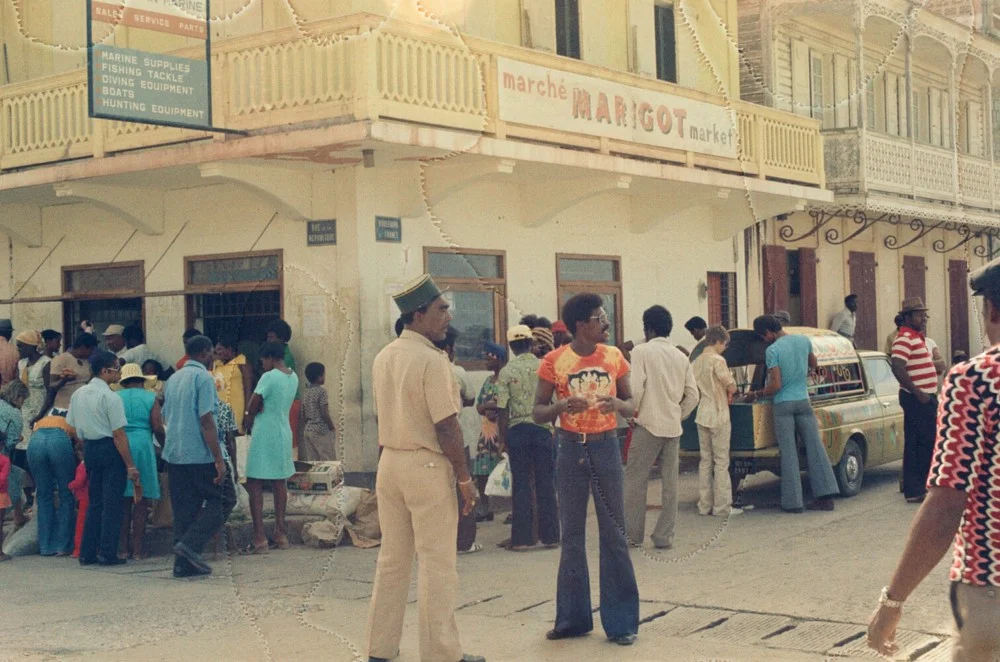

By the time I came around, he had already been across the globe a few times — which was in and of itself a pretty exotic feat for the era — but he was only just getting started. Joe and Ethel rewarded themselves for a good life of hard work by spending the second half of it, over thirty years, visiting places all over the world. At least once a year, they would take off — most often in Western Europe, but also Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, South America, Central and Eastern Europe, and probably quite a few more. When they’d return, the family would gather for an old-fashioned slide show. Ethel would prepare a platter of dried fruits and nuts, the screen would go up, lights would go down and the projector would flick on. What proceeded then would be a competition of memory for the small stories and events of their trip. My grandfather’s memory for detail was unassailable, but Ethel always had the last word.

Many years later, after he had died and it was apparent that I would continue the legacy of travel and photo-taking, my grandmother entrusted me with his many boxes of slides. They were highly unorganized and consisted of everything from loose negatives to filled carrousels to small, bulging slide boxes. Thousands and thousands of images. All un-labeled.

It’s taken me fifteen years to get it all together and scanned. I have barely started down the process of trying to figure out where these places are and what year they might have been taken. I may never know. In some ways, it’s not what really matters. I actually quite enjoy the mishmash of time and place that these images, in this scattered format, create. They come together exactly like my memory of him — a richly condensed man of great experience and joie de vivre.

What I love about these images (and this is only a very small taste of them) is that they are there to document the travel as much as the place. His images are heavily aware of being a visitor — in those days, foreign travel had a formality to it. In the images, you can see both the formulaic-ness of tourism but also a man who would climb to any height to get a better view than the crowds. He would do anything for a good shot — I watched him sneakily break off to go take a snap, many times.

I love the raw talent depicted in these photos. A high percentage of them are out of focus, which for me only adds to my appreciation for him. Focusing was hard, in those days — no electronics or fancy in-camera technologies. He learned it all on his own, with no training — and considering that, there’s a side story that develops with these images of a man who was learning a craft from love of subject backwards. Which is also how I learned photography.

My favorite image is one that I don’t recall ever making it into a family slide show. It features my grandmother driving an early 70’s Nova on a foreign beach somewhere. It’s a shocking image for me in so much as she never drove. Usually, Ethel was in the back of a stuffy Cadillac — she suffered from a deep, nearly-disabling anxiety and her overly-dramatic fears made her almost comically over-concerned about every little thing. Seeing her here, carefree and outrageously off-the-beaten-course adds an entirely different look at their relationship and adventures together.

In the end, your photographs should not only show a great life, they should convey what you loved. Enjoy the following story of the man who loved to travel.