“Migration vs Traveling” explores the double standards in the way we stereotype migrants as “something negative” and travelers as “something positive,” and proposes an idea on how to overcome them. This video was awarded the Prix de l'EYP 2015, the European Youth Press's award, for the best journalism on media freedom (category video), during the European Youth Media Days 2015 at the European Parliament in Brussels. It was also invited to be continuously screened to EU officials during the Dutch EU Presidency in the Netherlands in 2016.

Nomads of Mongolia

Life in Western Mongolia is an adventure. Training eagles to hunt, herding yaks, and racing camels are just a few of the daily activities of the nomadic Kazakh people. Filmmaker Brandon Li spent a few weeks living with them and experiencing one of the most unique cultures in the world. Saddle up and enjoy the ride.

Rare Glimpse into Antarctic Underwater World

An underwater robot has captured a rare glimpse beneath the Antarctic sea ice, revealing a thriving, colorful world filled with coconut-shaped sponges, dandelion-like worms, pink encrusting algae and spidery starfish.

The footage was recorded on a camera attached to a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) deployed by Australian Antarctic Division scientists under the sea ice at O’Brien Bay, near Casey research station in East Antarctica.

Explore Aotearoa with Ludovic Gilbert

Aotearoa is the Maori name for New Zealand. Ludovic Gilbert and his wife spent 3 weeks there for their honeymoon, and traveled more than 4,000 miles through Christchurch, Akaroa, Lake Tekapo, Te Anau, Wanaka, Fox Glacier, Punakaiki, Kaiteriteri, Wellington, Tongariro, Taupo, Whengamata and Auckland. Here are the fantastic landscapes, beautiful people and lakes with amazing colors they found.

How to Find Authenticity in a Globalized World

Why do we travel?

For those of us privileged enough to be able to travel voluntarily, reasons often include becoming more fully ourselves and experiencing something genuinely different. This desire for authenticity, in ourselves and in that which we perceive to be other and outside our current experiences, is widespread enough to be noticed and exploited by the tourism industry, with signs reading “experience the REAL Thailand” and “find yourself in Bali”.

Seeking authenticity in our travels comes from a good place. It highlights our desires for genuine interactions with other human beings, for learning about the experiences of those with different life paths and identities, and possibly even for utilizing our privilege to support real people instead of opportunistic corporations removed from the locations in which they operate.

However, as is the case with many good intentions, this desire for authenticity can be harmful. Much of this harm stems from a strict and arbitrary idea of what counts as authentic and the fact that the privileged traveler has the power to decide what makes the cut. For instance, while spending 3 months in Zimbabwe a few years ago, I asked several friends what their cuisine had looked like prior to British colonization. As their current main foodstuff, a labor-intensive dry porridge called sadza that holds its shape when spooned onto a plate, is made of cornmeal, it couldn’t have existed prior to the transfer of corn to Africa from the Americas. I’ve had similar questions about Italian, British and South Asian cuisines before tomatoes, potatoes, and chili peppers made a similar journey. From my perspective, sadza was a colonial by-product, as was the black tea served alongside it. When I shared this view with my friends, the effect was clear: my strict and arbitrary definition of what could be considered authentically Zimbabwean delegitimized and minimized their identity and emotional ties to the food they knew and loved.

This highlights a tendency in our search for authenticity - to regard older traditions and cultural forms and those which predate recent cultural exchange as more authentic. This viewpoint is understandable, especially as a reaction against the infiltration of Western corporations such as Coca Cola into most crannies of the world, including a remote village in eastern Zimbabwe, and the Westernization of many popular tourist destinations, from food offerings to street signs. Yet the reality is that all places and peoples are dynamic. Historical and current globalization, the movement of people, ideas and things, has fostered cultural exchange and the transformation of traditions over time. Cultures also evolve without interaction with outside forces. When we define authenticity as similarity of a particular part of a culture to its version at a particular point in history, we mistakenly regard people and places as static, freezing them in time.

Aside from our tendency to award authentic status to more longstanding traditions, we also withhold this label unless the cultural form feels “other” enough and different enough from our cultural forms to be plausibly untainted by them. But ironically and cruelly, our globally dominant culture and associated language simultaneously demand conformity for material gain and social acceptance. Without this, the inherent amount of difference between cultures would render many practically inaccessible to travelers.

When we travel in search of authenticity with these unconscious assumptions and unfair expectations lurking in our minds, we often end up unknowingly demanding that locals perform a certain version of their culture for our tourist dollars. The result is a paradox: we want specific historical versions of cultures that are different enough from our own to feel authentic but similar enough to actually understand and enjoy. We travel to search for authenticity, but by traveling we reinforce the global dominance of our culture which demeans and degrades the other cultures we seek to experience. Seeking authenticity obscures it from us.

It also shortchanges us. Traveling with a particular idea of what authentic looks, tastes, smells and sounds like creates expectations and takes our attention away from what is. When we’re less present with ourselves, where we are, and the people around us, we’re less likely to feel deeply satisfied in addition to being more likely to cause accidental harm.

So, what to do? Here are some guidelines for navigating these realities:

1. Take people and places as they are now

Don’t force them to live up to some idea conjured up by tourist companies, history books, or your own mind as the antithesis to your everyday life. Don’t expect them to be similar enough to be accessible and understandable to you. On the flip side, don’t expect them to be different enough so that you can feel like you’ve escaped your daily grind and your culture. Manage your expectations or avoid forming them. Of course, it is very hard to travel with no inkling of what you’re going to find once you arrive, but be honest with yourself. Why are you drawn to particular places? What expectations do you have? Find balance - have just enough foresight to plan yet not enough to keep you from accepting what is when you’re there. The best days often come when you're not expecting them.

2. Only do what you actually want to do

Travel guides and guidance from friends are riddled with “must sees”. What if nothing on those lists strikes your fancy? I almost always skip museums when I travel. While you could argue that I’m missing out on important historical context, I would argue that I’ve never absorbed this information from museums even when I’ve forced myself to go to them. Luckily, each place and culture and even person is unfathomably complex and contains endless dimensions. Engage in the same activities you enjoy in back home and try new ones which feel right. Do you in a new place. By living your truth while traveling, you’re more likely to find authenticity in the place you’re visiting.

3. Engage other cultures carefully

Cultural exchange can be mutually beneficial but it can also be oppressive. Acknowledge the power dynamics in your interactions with non-travelers. Be aware that you probably embody and therefore unknowingly reinforce ideals that other people must conform to in order to gain social currency and acceptance. And make sure your engagement with other cultures doesn’t cross the line into appropriation. Appropriation can take many forms, but it almost always involves travelers benefiting materially from or being praised for a particular cultural form while the people to whom that cultural form belongs are ridiculed, persecuted, or exploited for it. Engage from a place of humility to learn, not to seek validation or make money. Always respect the stated boundaries of engagement, and where appropriate, wait to be invited.

SARAH LANG

Instigated by studies in Sustainable Development at the University of Edinburgh, Sarah has spent the majority of her adult life between 20+ countries. She is intrigued by the global infrastructure that produces inequality and many interlocking revolutionary solutions to the ills of the world as we know it. As a purposeful nomad on a journey to eradicate oppression in all its forms, she has worked alongside locals from Sweden to Zimbabwe. She is a lover of compassionate critique, aligning impacts with intentions, and flipping (your view of) the world upside down.

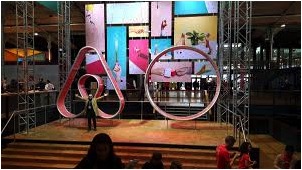

Travel Volunteerism: Airbnb to Offer Users a Way to Help Local Communities

After 8 years in business, travel accommodations company, Airbnb is expanding its platform and the services it offers by launching Airbnb Trips. Initially a peer-based home rental service, the company went on to partner with major travel brands like Delta and American Express for airline miles, points, and business tools for users. Now, Airbnb’s co-founder and CEO, Brian Chesky, is rolling out plans to do more than just provide customers with access to private lodging; he also wants to provide travelers with things to do once they reach their destination. During November’s Airbnb Open, a travel and hospitality festival held in Los Angeles, Chesky told the audience that planning a trip takes longer than the actual trip, and his company wants “to take the research project out” of travel.

On Airbnb’s updated app, users can now create an itinerary under “Trips” and book “Experiences”— activities that range from those of typical tourism to exclusive events and meet and greets. About 1 in 10 of these Experiences are allocated for “social impact experiences,” which airbnb.com describes as volunteerism and getting involved with a “cause you care about [where] 100% of what you pay goes directly to the organizations.” Some of these causes relate to social inclusion, mass incarceration, and animal rights, and activities include dance, gardening, feeding the poor and composing music. These Experiences will reportedly cost between $150-$250, and Airbnb has waived its commission for social impact experiences.

Chesky says that Experiences will be available in 12 destinations—Detroit, London, Paris, Nairobi, San Francisco, Havana, Cape Town, Florence, Miami, Seoul, Tokyo and Los Angeles. He also says the company will expand Experiences to 50 additional cities around the globe this year, with the ultimate goal of being able to provide Experiences in every Airbnb host location.

Experiences, Chesky says, are ways to immerse oneself into local communities and are a part of a “holistic travel experience.” Social impact experiences are identified on the app by a “social ribbon.” The site notes that participating in this type of social volunteerism allows travelers to “join with passionate locals” and “leave your mark on the community.” Social impact experiences are always hosted by charities and non-profit organizations. Chesky also says that Airbnb has a partnership with the Make-A-Wish Foundation—the charity for children with life threatening illnesses—and that Airbnb will be granting “a wish a day.” This will be done via donations, accommodations, and “transformational experiences” according to its website.

Brian Chesky, the founder of Airbnb.

Learn more at airbnb.com and on their YouTube channel for a look at Social Impact Experiences at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CwwMT05jqfU&feature=youtu.be

ALEXANDREA THORNTON

Alexandrea Thornton is a journalist and producer living in NY. A graduate of UC Berkeley and Columbia University, she splits her time between California and New York. She's an avid reader and is penning her first non-fiction book.

The Truth about Socialized Medicine around the World

In 2010, I moved to Australia from the United States and stopped in Thailand to go diving. While walking back to my hotel, I started to have trouble breathing. When it didn’t go away, I took myself and my chest pain to the emergency room. It was sparkling clean and almost empty; the young Thai doctor was thorough and gentle, and I walked away with an EKG, a chest X-ray, and a prescription for antibiotics. The total cost of my visit, for which I had to pay out of pocket due to not being a Thai citizen? About $40 USD.

There is a lot of misinformation passed around in the United States about socialized healthcare. You can wait a year without treatment. There are only two MRI machines in all of Canada. Nobody actually likes the system, or uses it. But the one thing most Americans never do is actually use universal health care. So I asked residents of multiple other countries to tell me what their experiences were like.

ISRAEL

Health care in Israel is universal and participation in a medical insurance plan is mandatory. All Israeli citizens are entitled to basic health care as a fundamental right.

Abby: “I never used the medical system for emergencies. Doctor’s offices seemed more like walk-in clinics than private practices, but Tel Aviv is very crowded. Even with an appointment, wait times were often 40-60 minutes.

I paid small co-pays, only to see specialists. Generally, the system was very low-cost and easy to use. I had to pay for prescriptions, but they were very cheap, especially compared to the States. A downside for me was that, while the doctors spoke perfect English, often the receptionists, nurses, and other office workers didn’t, so I had to get my Israeli boyfriend to make the appointments for me.”

ENGLAND

The NHS is the state healthcare provider in the UK. The service is free at the point of use; services are free, and running costs are covered by taxation. Private insurance is used by only 8% of the population of England.

Tim: “I have used the NHS many times, although, where possible, I go to private providers to save resources. Emergency work is almost always done on NHS. My mother was recently diagnosed with lung cancer and the NHS could not have moved faster; she also gets a choice of where she can be treated. She got a biopsy yesterday, the results ought to be back in five days and then treatment will start immediately. You would not receive any better with private insurance (and I say that as Tory).

Going to Emergency (A&E) is usually good, which I know from all my rugby injuries. You can get patched up and sent on your way in a reasonable amount of time. Getting a GP appointment (a general doctor, who will give you a referral), on the other hand, is almost impossible. The waiting time for my area is about three weeks. On the whole, the NHS is a good thing. It still has many flaws, though, and is in desperate need of a restructuring.”

AUSTRALIA

Australia has universal healthcare, called Medicare. It covers all general medical care, but some services are only partially covered and individuals pay a gap fee – this is usually still reasonably affordable, however. Individuals who earn high annual salaries are encouraged to take out private insurance.

Jenny: “I had an abnormal pap smear at my GP’s office, and she sent me a referral onwards to the Royal Women’s Hospital. I’ve had a lot of anxiety about pap smears in the past, and she specifically notified them about these issues. Since my issue was not urgent, she told me to expect a wait of several months for an appointment. The hospital recommended a colposcopy.

I contacted the patient advocacy department at the hospital and asked for assistance with my anxiety and PTSD. On the day of the procedure, all doctors and nurses were helpful and calming, and I managed to get through the experience without too much fear. They recommended that I get laser surgery to remove the abnormal cells from my cervix.

All of this has been totally free -- which is to say, paid for by Medicare. My original appointment for the pap smear was in May, and my laser surgery is scheduled for December...I received the appointment at the hospital in August. The abnormalities that showed in my report were not of an emergency nature; for similar issues, the brochure I received said patients can sometimes wait up to a year for treatment. I really appreciated the personalized care and support I received; it would have been so difficult to worry about payment while trying to deal with my emotional reactions to these procedures.”

FRANCE

All French residents pay compulsory health insurance, which is automatically deducted from paycheques. Patients pay fees at the doctor or dentist, which are then reimbursed 75-80% by the government, except in the case of long-term or expensive illnesses (such as cancer), which is reimbursed at 100%

Aliyah: “My father, who is Kenyan, was on a business trip in Paris. He tripped getting out of the subway and had a nasty gash above his eye. He was rushed to hospital, treated and held overnight for one or two days. When he was released, with medication, I kept bracing for the bill. None came. I told Dad to ask about it and he did. Answer: there is no bill, it is your right to be treated for free under our system.”

SWEDEN

The Swedish health care system is government-funded, although private health care also exists. The health care system in Sweden is financed primarily through taxes levied by county councils and municipalities.

Kelly: “Giving birth, tests, and one ultrasound were free. They charged me for extra ultrasounds and non-essential testing. The only thing they give you at the hospital for the baby is diapers, cream, and formula.

Generally, in Sweden, the health care works if you are dying or having an emergency. As long as everything's normal, no one will look twice at you or even WANT to see you more often than needed. The drop-in clinics (vårdcentral) never have enough staff or resources, so if you need to see a doctor, you exaggerate your symptoms or they just tell you not to bother coming in.

I have been struggling for 3 months to get a pediatrician for my daughter. Since I started trying, we went to the emergency room once, the nurse’s office 4 times, and I called the helpline a million times. No-one wants to actually see her.”

CANADA

Canada's health care system provides coverage to all Canadian residents. It is publicly funded and administered on a provincial or territorial basis, within guidelines set by the federal government.

“Everything is covered, whether it's something minor or surgery under anaesthetic. I've had MRIs, CT scans, x-rays, ultrasound, mammograms, you name it. The times I've had to go to emergency, I've received variable treatment, depending on the hospital. My longest wait was 13 hours. The shortest was ten minutes when I was afraid I had an aneurysm. For that one, I saw a specialist right away, which was also free. When my father had necrotizing fasciitis, he went to the hospital and was treated immediately. If he'd received treatment even 30 minutes later, he may very well have lost his leg or worse. In Canada, vision and dental are not covered by universal health care, and neither are things like physiotherapy, massage therapy, or alternative medicine like acupuncture, chiropractors, and so on. That being said, private medical insurance often covers a certain percentage of these things. Prescription medicine is also not covered by federal system, but between provincial plans and private insurance, can be greatly reduced in price if not free. Flu shots are free every autumn, and I remember getting vaccinated against rubella at school when I was a little kid. If you step on a rusty nail and go to emergency, your tetanus shot is free. Travel vaccinations and more unusual vaccinations, however, cost money. When I planned a trip to South America, I went to a travel clinic. The consultation was free, but I had to pay for my yellow fever and cholera vaccines.

I wish vision, dental, and physio were covered by national health care, but I am so grateful that everything else is covered. If they weren't, there's a chance I might not have survived as long as I have.”

IN SUMMARY

The United States is one of the only developed countries that doesn’t provide universal health care for its citizens. A friend of a friend had a baby at 28 weeks (extremely premature); the baby was in the NICU for several months. Fortunately, they had very good health insurance and ended up only having to pay $250 of the $850,000 bill -- but they were lucky. The United States healthcare system is a labyrinthine mess where insurance administrators make possibly lifesaving decisions about patient care, rather than doctors. The care you receive is based on what you can afford, not what you need.

Even with these astronomical costs to the consumer, the U.S. government still ends up paying more per capita for healthcare than countries with socialized medicine. Citizens of the U.S. have a life expectancy lower than other developed nations, and more elective surgery at higher costs...and paying more does not mean the service is better, as the U.S. also has fewer doctors than comparable countries. The systems elsewhere are not perfect, but the perfect is the enemy of the good: anything would be better than ending up in debt for the rest of one’s life, or worse, suffering (and dying) in silence because the cost of treatment is too high.

CLAIRE LITTON

Clair Litton was born in Canada, moved to the United States, went to graduate school in Australia, and recently relocated to Sweden. She has written for a series of online and offline magazine, and once had a young adult novel picked up by an agent, who then had to back down due to signing a little book called "Twilight." You can most commonly find Claire arguing about human sexuality and watching her toddler open and close doors.

5 Ways to Make a Positive Impact while Traveling in Bolivia

As one of the poorest countries in Latin America, Bolivia is a nation that, more than most, would benefit from your tourism. However, a historic lack of investment in infrastructure throughout the country and a reputation of political instability has left this nation neglected by foreign visitors.

Despite being more difficult to explore than neighboring Peru, Argentina or Brazil, Bolivia is a country that shouldn’t be missed. It has a wealth of diversity of natural landmarks, from the soaring Andes Mountains to the huge plains of salt flats to the Amazon jungle, as well as tiny communities inhabited by local, indigenous people ready to share their culture with curious travelers – and who really benefit from the income that responsible, considered tourism brings.

So here are 5 ways that you can do your bit to make a positive impact when you’re traveling in Bolivia.

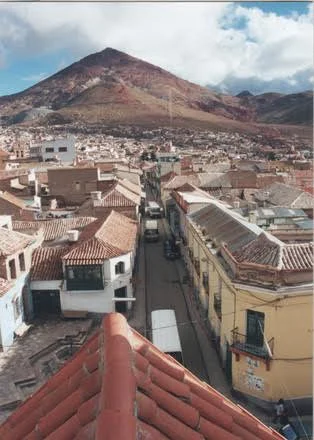

Potosi

1. Go Local

Many of us are more comfortable booking tours ahead of our trip to ensure that our visit runs smoothly and no time is wasted. But it can be difficult to know exactly how much of the money you’re paying is being invested into the country you’re visiting and whether the local people there are actually getting a fair deal.

Instead, booking tours when you arrive or online with locally-run, sustainable tourism agencies based in Bolivia will insure 100% of your money goes directly to the local people, meaning you’ll have a positive, responsible impact through your tourism.

Luckily, Bolivia has a growing number of excellent, responsible companies to choose from. Some of the best include:

Condor Trekkers based in Sucre is a hiking tour agency that leads treks into remote villages in the Andes, with hikes passing along stretches of preserved Inca trail and to landscapes potted with dinosaur footprints. They feed all of their profits back into the communities through which their tours pass to support locally-run, sustainable development projects.

The San Miguelito Conservation Ranch, a short distance from Santa Cruz, is a private reserve and conservation project that protects a section of wetlands acknowledged as having one of the highest concentration of jaguars in South America. This eco-tourism project runs tours to spot the big cats, birds and other wildlife in the reserve and uses the profits to maintain this important habitat.

Nick’s Adventures, another company based in Santa Cruz, runs a series of tours throughout the country, including spotting big cats in Kaa Iya National Park, the only park in South America established and administered by indigenous people. This agency supports sustainable development by providing employment to local people as drivers, guides and cooks and replaces any cattle killed by jaguars to stop ranch owners from shooting the cats, thus meaning that no jaguars or other native wildlife have been killed since Nick’s Adventures began this project.

La Paz on Foot runs walking tours in La Paz itself, as well as hiking trips further afield to indigenous communities. These communities receive much of the profits and La Paz on Foot have established a series of sustainable development and biodiversity conservation projects.

Solace Trekking Tours based in La Paz takes visitors on cultural tours to indigenous communities to take part in workshops about dancing, weaving and other traditional activities, as well as running climbing, biking and hiking trips to remote villages. Some of the profits of these tours are used to support the indigenous communities that are visited, as well as others who are fighting to save their land and water from mining – something that is a real threat to both natural habitats and the livelihoods of local people.

2. Don’t bargain too hard

Like many Andean countries in South America, artisanal goods of fluffy llama wool jumpers and delicate jewelry are hawked by locals on their stalls in every city and travelers are always keen to get a good bargain. But unlike parts of Asia and India where haggling hard is par for the course, in most of South America and particularly Bolivia, it’s not always the case.

Yes, you should expect prices to be higher for you; unfortunately, as a foreigner you will be charged an inflated rate. Negotiating a small reduction is sometimes possible, but most of the time, you shouldn’t try and push for prices that are vastly lower.

Shop around a bit and get a feel for what things cost, but follow your conscience with what you spend. Saving a few dollars on a jumper probably means very little to you in the long run, but in a country where 45% of people live in poverty and earn less than $2 a day, avoiding haggling sellers into the ground is the responsible thing to do.

3. Get off-the-beaten track

Most travelers in Bolivia stick to the main gringo triangle: La Paz, Sucre and Uyuni. And while these are certainly highlights of the country, other places also need the investment that tourism brings.

Towns such as Rurrenabaque, the best place in the country to access the Amazon Jungle, really need the support of responsible tourists. Once receiving lots of Israeli visitors (because of an Israeli who got lost in the jungle here a few decades ago and wrote a book about his experiences), numbers have dwindled since the Bolivian government decided to support Palestine and introduced a fee for Israelis entering the country.

Tourism is currently at a record low in the region and desperately needs travelers who are keen to visit. Check out sustainable operators, such as Mashaquipe Eco Tours, who charge fair prices and work responsibly to protect the jungle.

Another under visited location is Potosi. Here you can actually visit Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain), the famed mountain of silver that was plundered by the Spanish conquistadores.

Potosi is now the poorest city in the country and while many local people still attempt to make a living mining the last remaining minerals in the mountain, tours with ex-miners such as with Potochji tours, located in Calle Lanza, provide another option. Visitors can enter the mountain to see the terrifying conditions and ensure that their money supports ex-miners and the mining unions that now operate there.

4. Stay and volunteer

One of the most profound ways that you can help to support social development in Bolivia is by staying for a period of time to volunteer with grassroots projects. I’m always hesitant to volunteer for less than at least three months; I know that it takes time to learn about the organization and how best you can support its work.

In Bolivia, where few people speak English and where the culture is far more reserved than in a lot of other Latin American countries, it can definitely take time to start feeling like you’re making an impact.

Unfortunately, 90-day visas are the norm for most travelers arriving into the country, which can put a time limit on your volunteering. However, a visa of up to a year is not impossible to come by, but does require you to put a lot of effort into acquiring the necessary papers.

There are plenty of organizations that need your help, including Up Close Bolivia and Prosthetics for Bolivia in La Paz, Sustainable Bolivia in Cochabamba, Communidad Inti Wara Yassi in the Bolivian Amazon and Biblioworks and Inti Magazine in Sucre.

5. Or become an ambassador

But if you can’t commit to volunteering, how about becoming an ambassador or fundraiser for a charity based in Bolivia? While travelling in the country, take the opportunity to visit some of the many volunteering organizations to get an idea of what they do. When you’re back home, it’s easy to find a way to support their work.

You can become an ambassador who promotes the charity to their friends and social media followers, as well as signing up to make a regular donation. You could also volunteer long-distance by supporting fundraising efforts or helping with their social media accounts. Most importantly, you can spread the word about what they’re helping to achieve and find other volunteers or sponsors who can support their efforts.

Ultimately, Bolivia is a fascinating country to visit and so by traveling responsibly and considering how you can make a positive impact as a foreign tourist will support social development projects in increasing the quality of life for the Bolivian people.

STEPH DYSON

Steph is a literature graduate and former high school English teacher from the UK who left her classroom in July 2014 to become a full-time writer and volunteer. Passionate about education and how it can empower young people, she’s worked with various education NGOs and charities in South America.

Take Only Memories, Leave Nothing but Footprints

ETHIOPIA: Suspended in Time

The moon shines brightly, as white robe and candle mark the lines of pilgrims winding their way up the hillside, to reach the ancient rock-hewn churches of Lalibela — a sacred place for those of the Christian faith since the 12th century.

According to the legends, men and angels worked together to construct the remarkable rock-hewn churches of Lalibela — the men working through the day and the angels taking over during the night.

Many historians believe that these great monolithic churches were commissioned during the reign of Saint Gebre Mesqel Lalibela, who ruled Ethiopia in the late 12th century and early 13th century, when the town was known as Roha. When Lalibela, whose name means “the bees recognise his sovereignty” in Old Agaw, was born, it is said that a swarm of bees surrounded him, which his mother took as a sign of his future reign as Emperor of Ethiopia. So the mythos tells us, Lalibela later visited Jerusalem, and after its capture by the Muslim caliphate in 1187 he swore to build another such sacred place of pilgrimage in his own country.

Each of Lalibela’s eleven churches was carved from a single piece of solid rock to symbolize spirituality and humility. The churches seem timeless, painstakingly excavated from the ground itself. It is believed that they were constructed first by digging out a kind of moat and were then hewn from the square rock that remained. The degree of craftsmanship and countless hours of heavy manual labour that it must have taken to carve out these wonders with hand tools alone is astounding. The churches are connected through a labyrinth of tunnels and sit beside a small river, called Jordan, and many other features also have Biblical names.

Just as astounding as the architecture, is that the churches have been in continuous use throughout the centuries since they were built.

Today, Lalibela is a town of no more than ten thousand people, but over a tenth of those are priests. Ritual and religion are the twin fulcrums upon which life in this place spins. Many times a year, there are processions, fasting, dancing, and the sound of many voices lifted up in song.

I feel privileged to have been in the holy city of Lalibela on many occasions and it continues to be one of the most fascinating photography trips I take anywhere in the world. It is a jump back in time, a photographic journey beyond compare. With the churches dimly lit by flickering candles, surrounded by faith and roughhewn rock — it is an entire world suspended in the 12th century.

Easter week in Lalibela is the most extraordinary in the year, when many thousands of devotees dressed in white will gather from all over the country, and father afield, to profess their love and Christian faith.

We land, and I arrive at the tiny, ancient airport terminal. To the left is an unmoving, rusted out conveyor belt with no hope of resurrection. Dragging my bags along behind me I reach the famous ‘Shuttle’. We are told to put the bags around back in the trunk. It is jammed, of course.

A few people toss their bags on the roof and the rest keep them on their laps once seated. I find a seat wedged between my bags and the stairwell, ending up intimately, uncomfortably close to my seat-mate. After a flat and long slow climb we reach the town on three and a half wheels.

“Ferengui... Ferengui...” (Foreigner... Foreigner...), I hear them murmuring amongst themselves. The time is 5:30 in the morning, and it is still dark. The inside of the church is small, austere, and it is difficult to move around discreetly by oneself let alone with a camera, and no cloak to help me meld with the darkness so thick that the eyes can hardly adjust. There is a candle here and there, occasional light through a tiny upper window, and the sudden glare of an opening door. Precious little else to see by.

The moon shines brightly over the hillsides and the lines of ascending faithful are seen thanks to the candles they carry up towards the church. In the morning half-light, the first chants begin. Voices lift.

Suspended in a parenthesis of time, I am witness to the rising dawn over the year 1100, as the first light breaks free of the horizon.

Swathed in long white robes, men and women come up the hill in silence. The lines of the path are drawn in the darkness by cloth and candle.

I have found a spot to wait in, where the faithful will have to pass by me. The more timid among them hid their faces in their cloaks, but the less so look at me squarely in the eyes. No aggression. Simply curious, trying to discern what on earth I am doing up here before dawn, if I am not here to pray, and what I am so patiently photographing.

The hours seem like moments, and I am alone, though among many. The fervor of the devotees as I move through the shadowed churches touches me deeply. These scenes, even for a skeptic who tries to stay propped behind his camera and maintaining distance, are magical. Moving.

HARRY FISCH

Harry Fisch is a travel photographer and leader of photo tours to exotic destinations with my company Nomad Photo Expeditions. He is also a winner and loser of the 2012 World National Geographic Photo Contest.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA

VIDEO: Papa Machete in Haiti

"Papa Machete" is a glimpse into the life of Alfred Avril, an aging subsistence farmer who lives in the hills of Jacmel, Haiti. He also happens to be a master of the mysterious martial art of Haitian machete fencing, also known as Tire Machét.

Teaching about the practical and spiritual value of the machete—which is both a weapon and a farmer’s key to survival—Avril provides a bridge between his country’s traditional past and its troubled present. The film documents his proud devotion to his heritage and his struggle to keep it alive in the face of contemporary globalization.

10 Places to Visit Before They Disappear from the Planet

Planet Earth is home to millions of beautiful animal and plant species, thousands of iced peaks, vast rainforests, and gorgeous islands. But climate change is causing our home to change rapidly. Much of the planet’s natural beauty is disappearing, only to be found in history books and television shows.

As the traveler in you beckons, here are some pristine spots around the world to visit before they disappear in the next few decades.

Great Barrier Reef (Australia)

Photo credit: Flickr - Kyle Taylor

One of the seven natural wonders of the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Great Barrier Reef has been ranked by U.S. News & World Report as the best travel destination this year. Meanwhile, rises in sea temperature and ocean acidification have been threatening the very existence of the coral reef. Tiny algae living in the coral called zooxanthellae are responsible for the beautiful colors, and when conditions change, these organisms leave the area, which leads to mass coral bleaching. 93% of the reef has been affected by the bleaching epidemic. The Great Barrier Reef may not be around for much longer as global warming continues to affect its ecosystem.

Joshua Tree National Park (US)

Joshua trees are extremely distinct desert plants located in the Mojave Desert, mostly in Joshua Tree National Park in California. Named by Mormon travelers for their supposed resemblance to the prophet Joshua, these trees are suffering from the drought that’s swept California in the past several years. The Mojave Desert hasn’t received its average 5 inches of precipitation in years and these desert trees are hurting. In the past 7 months, only 1 inch has fallen, preventing the trees from reproducing. By the end of the century, the park may need a new name.

The Dead Sea (Palestine/Jordan)

Photo credit: Flickr - tsaiproject

The Dead Sea, home of the lowest elevation on Earth and almost 10 times as salty as an ocean, is losing 2 billion gallons of water a year. This is because of large-scale mining operations and the diversion of water from the Dead Sea’s main water source, the Jordan River. More than 3,000 sinkholes have opened up on the shoreline, leaving craters as deep as 80 feet into the ground. If you’re keen on floating in this natural wonder, better get there sooner rather than later.

Glacier National Park (US)

Photo credit: Flickr - Troy Smith

Glacier National Park has seen a 2 degree Celsius rise in temperature since 1990. While there were 150 active glaciers, just 25 remain today. The loss of 125 glaciers in a 165-year period is an acute representation of the losses the world will face as climate change accelerates. Scientists predict that all glaciers in the park’s main basin will have disappeared by 2030. The clock is ticking for Glacier National Park.

Galápagos Islands, Ecuador

Photo credit: Flickr - pantxorama

The Galápagos Islands are famous for their biodiversity, one of the reasons Charles Darwin chose to study and develop his theory of evolution there. But, once again, climate change is drastically changing the makeup of the islands. An increase in ocean temperature has caused reef die-offs and algae blooms, as well as the loss of native species, while land animals have been affected by the decline of marine life. If sea levels continue to rise, the nesting grounds of the Galápagos penguin will disappear. The Ecuadorean government has been preparing for this by building “penguin condos” inland, and by imposing restrictions on tourism to the islands.

Machu Picchu, Peru

Home to the ruins of the medieval Inca Empire, Machu Picchu has become one of the top destinations for tourists who want to explore the ‘Lost City’ that was rediscovered in 1911. Although it stands at a majestic 2,430 meters above sea-level in a cloud forest high up in the Peruvian Andes, it has been affected by erosion, landslides, and more visitors than it can handle. The historic site could soon be wiped out unless authorities take precautionary measures, such as controlling the flow of tourists, and protecting it from urban encroachment.

Photo credit: Dan Doan

Mt. Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

85 percent of the ice on Africa’s tallest peak, immortalized by Ernest Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” has already melted away during the last century. Once again, climate change and deforestation are the main drivers of this rapid depletion. Scientists have predicted that the mountain’s glaciers, thought to be at least 10,000 years old, might completely disappear from this peak within the next two decades.

Madagascar Rainforest

Once 120,000 square miles, the Madagascar rainforests off the coast of Africa are now down to 20,000 square miles. The forests are being eroded by human activities like deforestation by logging and burning wood. About 75 percent of the species found here, like flat-tailed geckos, tomato frogs, and comet moths, live nowhere else on earth. Many of the island’s unique species have never been recorded, and it is feared that these species will be lost to the world before they can ever be discovered.

Tomato Frog

Photo credit: Francesco Veronesi

Chameleon unique to Kirindy Forest, Madagascar

Photo credit: Frank Vassen

Maldives

Photo credit: Mac Qin

This nation is comprised of hundreds of beautiful islands in the Indian Ocean and is the lowest-lying country on Earth. It could also become the first country to be entirely submerged by water within the century if sea levels continue to rise. The Maldivian government has actually bought land in other countries for citizens who might be displaced because of climate change.

Sundarbans, India and Bangladesh

Located on the India- Bangladesh border, the Sundarbans is a low-lying delta region in the Bay of Bengal, home to numerous endangered species, including the world’s last population of mangrove-dwelling tigers. However, due to pollution, deforestation, and continued reliance on fossil fuels, sea levels here are fast rising, causing the coastlines to rapidly erode. Thousands of inhabitants of this World Heritage Site have been displaced already. In the years to come, the environment will continue to change in dangerous ways.

Time is running out to visit these destinations! Our world is filled with unbelievably beautiful wonders of nature, but as climate change continues to affect the planet these places will no longer remain. It’s important we remember not to take the beauty of this planet for granted.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GLOBAL CITIZEN

GARIMA BAKSHI

Garima, a Digital Content Intern at Global Citizen, believes that each person is a reservoir of power and potential that can be utilized positively. She brings her love for feminism, spicy food, and Harry Potter from her hometown of New Delhi.

MADELINE SCHWARTZ

Madeline is also a Digital Content Intern at Global Citizen. She has always been passionate about this world and social justice. She plans to study oppression's effects on culture at Oberlin College, and is constantly searching for new ways to express herself.

KOREA: The Inner Lives of Korean Monks

Almost entirely cut off from the world, enclosed by mountains that resemble the petals of a lotus flower, lies one of the jewels of Korean Buddhism. As winter melted into spring, Alexandre Sattler lived alongside the monks, privileged to witness their daily lives and rituals.

"TEMPLE OF THE SPREADING PINE"

Looked upon as one of the Three Jewel Temples of Korea and renowned for its teaching of dharma — the eternal law of the cosmos, inherent in the very nature of things — today Songgwangsa is one of the foremost temples in the world for practising Korean Buddhism. In search of spiritual awakening, monks, pilgrims, believers and tourists all find their way here, to learn, meditate and exchange ideas.

Around 1190, Jinul, who was a master of seon, the Korean variant of Zen, stopped in front of an abandoned temple at the centre of a mountainous valley, where an abundant stream was flowing. He planted his stick in the ground and announced to his followers that in this place — from then on known as Gilsangsa — they were going to build a new temple.

According to legend, the stick took root, and is still waiting for Venerable Jinul to be reincarnate before flowering. This is how, at the very heart of what has become Jogyesan Provincial Park, a few tens of kilometres away from the sea, the prestigious temple of Songgwangsa — or “the Spreading Pine,” in keeping with one of its etymologies — now stands. Held to be one of Korea’s greatest national treasures, it currently falls under the jurisdiction of the Jogye Order, one of the branches of Korean Buddhism.

Almost entirely cut off from the outside world, Songgwangsa is enclosed by mountains, and wooden edifices occupy both sides of the stream which flows through the site. None of the spaces between the buildings is linear, as is often the case with traditional Japanese temples. Here, it seems as if man has reconciled himself to nature without attempting to impose upon it. Snakelike pathways move from one temple to another according to the whims of the contours.

To erect the temple, the monks-turned-builders depended on feng shui doctrine, favouring the feminine energies, or yin, of the place. It is said that the surrounding mountains resemble the leaves of an enormous lotus flower, whose stamens are represented the temple buildings. So as not to impede the flow of energies, the monks chose not to draw upon dome-like stûpa — synonymous with yang, or masculine energy — unlike the custom in other Korean temples.

I came to Songgwangsa in February, at the tail end of winter. It seemed as if Nature was still asleep. The sky was grey, the temperature barely more than five degrees. When the bus stopped at the terminal, the other travellers and I found ourselves standing at the foot of Mount Jogye. The climb up to the temple is magnificent. As you follow the banks of a waterway, slumbering pines appear out of the fog and the wind whistles softly in the bamboo plants. It takes around twenty minutes of quiet, contemplative walking to reach your destination.

Initially, I had thought that I would only spend four or five days at Songgwangsa, but the monks made me see that time should not be rushed, and that new things tend to come to us when we are prepared to receive them. On entering the reception room, I discovered first of all that I had been admitted on the basis of a misunderstanding. Journalists and photographers are usually sent to a different temple.

Despite this, I was granted an unadorned room with a mattress, blanket and pillow, which I would learn to fold carefully and tidy away in a little cupboard each morning. I came to realise that to write and take photographs, it would be necessary to be truly met with approval by the whole community. More than anything, I would need to commit myself to the daily rhythm of the monks, their rites and ceremonies.

After a time, I was accepted by the sangha. The monks became fond of coming to say hello and talk to me, and some of them regularly invited me to take tea in their cells. I formed a friendship with Dokejo Sunim, the senior monk in charge of instruction in dharma and also a photographer.

During my first week I learned to live as the monks do, following their teachings and taking part in their prayers, meals or daily tasks. But I was not yet allowed to capture the slightest image. It was actually only because every member of the assembled community gave their consent that I became the first photographer permitted to take shots of their ceremonial spaces, or of the incredibly intimate tonsure.

In fact, Dokejo Sunim told me that previously, no other professional had been trusted to take these kinds of photos, and that in all likelihood it would never happen again. For this reason, the photos I publish here are an exception of sorts. At the end of my stay, Dokejo Sunim even requested that each and every one of my shots be sent to him.

Upon my arrival at Songgwangsa, the monks had explained that the winter retreat was nearing its end, but invited me to stay until the first full moon of the new season. If I prolonged my stay, they suggested, I would be able to meet Venerable Hyon Gak Sunim, a monk well versed in English who would be able to have a more in-depth conversation with me. In the following weeks, although I became used to crossing paths with Venerable Hyon Gak Sunim, it was impossible for him to speak to me, as he had made a vow of silence for three months. So I decided to extend my stay and wait until the very end of his winter retreat.

“Buddhism is a science whose proposed theories are only proven after they have been experienced.”

I like this idea. They say that the Buddha used to end his addresses with the following, “Don’t believe what I tell you, experience it for yourselves.”

As spring took her first breath, so Venerable Hyon Gak Sunim emerged at last from his weeks of silence. He seemed happy about our encounter, which he led with incredible energy and presence. His voice often broke the room’s silence, and his words deeply affected me.

One day, I made the point that life in the temple felt distant from the material world lived in by much of humankind. I asked him my questions about meditation and the search for release which seems to be too inward-looking, while all around me I sense the urgency for change, to ensure a sustainable future for everyone. Why choose to pray here, I wondered, far from all of us, while we are in desperate need of spiritual light to make sense of our everyday actions and our place in the world?

“Prayers are like carbon reservoirs”

Venerable Hyon Gak Sunim explained to me that prayers are like trees, silently maintaining the vital balance of man and life on Earth. Each tree, no matter how large or small, acts as a “reservoir,” soaking up atmospheric carbon, unobtrusively helping to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and lessening global warming as a result. Skimming over a forest, you see only the trees and their impact remains invisible. It is the same with prayer.

Coming to Korea, I could not help but compare this country to Japan, where I had lived previously. Knowing that Hyon Gak Sunim had also lived in Japan, I asked if he could explain the difference between Japanese and Korean Buddhism. He told me, “In Japan, people eat with chopsticks. In India, with their hands. In Europe, with a knife and fork. In Korea, people eat with a spoon and chopsticks… but at the end of the meal, they all have a full stomach! Whatever the technique, the result is the same, Buddhism simply offers different routes into enlightenment.”

This story has only become a reality through the involvement of all the monks at Songgwangsa and the help of Yong Joo An and Jieun Lee. All my thanks go to them. Original text translated from French by Zoë Sanders, Maptia.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA

ALEXANDRE SATTLER

Alexandre Sattler is a photographer, traveler, and producer of audio documentaries on our planet's diverse cultures. With an aim to showcase our shared humanity and the environment, more of his work is available on through gaia-images.

In Search of Beauty in Antarctica

Traveling on a sailing ship built in 1911, the same era the last great expeditions braved the unknown and departed for the infinite and barren landscapes of the white continent, René Koster leaves on his own voyage in search of beauty, the beauty of emptiness and cold.

Thoughts of frozen ships trapped in ice-covered seas cross my mind.

Embarking on a voyage to the South Pole, I travel in a sailing ship built in 1911, the same era the last great expeditions departed for the unknown continent. I recall images of the photographers who joined these expeditions to report of the unexplored. Fascinated by their stories I head for the same circumstances as those of the early twentieth century.

I am on a journey of longing, to a time that once was. A heroic saga, filled with hardship and adventure, in an infinite, barren land.

This series of photographs, taken with modern equipment, references the past. Personally, I feel no need for the photographs to look as if they have been created with techniques of the early 1900s. This is why I have deliberately chosen to work in color; allowing the greyscale of the landscape to emphasize the blue captured in ice. In my search for the right images, I have tried to avoid as many elements of the present time as possible; things that would remind me of everyday life.

The calm misty weather gives me a sense of desolation and makes the whole world feel smaller.

The slow rate of traveling by sailing ship influences my way of taking photographs; I seek stillness, harmony and tragedy in these otherworldly landscapes. In search of beauty, the beauty of emptiness and cold.

RENE KOSTER

René Koster's work concentrates mostly on travel photography and portraits for magazines around the globe. Work from his Antarctica project was awarded The Travel Photographer of the Year. Check out his website here.

VIDEO: How to Travel the World with Almost No Money

Many people daydream about traveling the world, but all of them share the same excuse — lack of money. After years of traveling with almost no money, Tomislav Perko shows how it is possible for everyone to do the same, if they really want.

IRAN: A Look Inside

Impressions and moments captured from behind Iran's closed curtain, as Brook Mitchell traversed the Islamic Republic during the country's "Ten Days of Dawn" celebrations and rallies, to mark the anniversary of the 1979 revolution.

Each year on February 1st — the date Iran’s former supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini returned to the country in 1979, after 15 years of exile — the Islamic Republic begins its annual “Ten Days of Dawn” celebrations. The tenth day marks the date that Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s regime officially collapsed, and events are held throughout the country to commemorate the anniversary of the 1979 revolution.

The celebrations offer the state-controlled media the opportunity to portray a people united behind the country’s leadership, with appeals to a sense of nostalgia, national pride and Islamic unity. Just how much of this rhetoric really hits home with the people of Iran is hard to know.

Most travelers returning from Iran will tell you about the legendary hospitality and natural curiosity of locals toward outsiders.

This was certainly my experience. Traveling solo, spending time in both the major cities and some of the smaller, more remote and down-trodden settlements, I was always made to feel welcome. I also never questioned my safety, except for some white-knuckle taxi rides through Tehran.

My goal was simply to see and shoot as much as I could while I had the chance. I experienced few issues taking pictures, and especially outside the major cities people were surprisingly open to being photographed.

Below is Khaju Bridge in Isfahan at sunset. The bridge and its banks are a popular meeting place for young people and local families.

Despite the welcome, traveling at this time of year it was abundantly clear that some older attitudes die hard. Although much of the hype surrounding the anniversary of the 1979 revolution appeared to be artificially whipped up by the authorities, the sight of young children propped up on their parent’s shoulders, holding placards that called for the death of the Islamic State’s perceived enemies, was hard to ignore.

In the city of Yazd I clambered up some dodgy scaffolding to take the picture below, which was one of the more surreal experiences of my trip. Even as the revolution celebrations reached fever pitch, most people simply waved and smiled, despite the hostile sentiment.

The former US embassy in the capital city of Tehran remains in much the same state as shown in the movie Argo. Now something of a museum, complete with wax figures representing former embassy staff, it is only technically open to visitors a few days each year. Anti-American murals such as those below have long been part of the urban landscape in Iran.

From these grisly monuments and stark murals around the former US embassy, to the huge national protests, rallies, and celebrations held throughout the first ten days of February, there were constant reminders that reconciliation with the West still has some way to go.

Above: Khaju Bridge in Isfahan

However, not long after my visit a number of major steps towards this seemingly improbable reconciliation took place. Today, with the prospect of economic sanctions being fully lifted, the authorities are promoting the lofty goal of making tourism one of the country’s largest exports.

Below is an image of a fellow tourist who spent the better part of an hour posing for pictures for her friends at the beautiful Nasīr al-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz. The building is famous for the early morning light cast through its ornate stained glass windows.

Lifting the sanctions will hopefully remove two of the more significant difficulties faced by travelers to the country. At the time of my visit, Iran was almost completely cut off from the international banking system, leaving independent travelers with little or no access to funds, even in an emergency. This meant carrying all the cash I needed for my entire trip.

Above: Nasīr al-Mulk Mosque

Added to this was the famously difficult visa situation. I arrived into Tehran at 3.00am armed only with a letter of invitation, which had been paid for in advance via a numbered Swiss bank account. After a cursory check over my documents, a friendly though wary customs officer disappeared into a back room to discuss my situation with a superior.

After what seemed like an hour he returned, smiled, and welcomed me to the country with a crunching stamp across my newly minted visa. After all the tension, I half went to high five the officer — the pressure was off.

Yet these relatively minor inconveniences pale into insignificance compared to the challenges the Iranian people have had to endure under the crippling economic sanctions brought on by the bluster of their uncompromising, theocratic leaders. Hyper inflation had brought their country’s economy to a grinding halt.

Below is a man bearing a placard with images of the supreme leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, and the ‘the eternal religious and political leader of Iran,’ Ruhollah Khomeini.

The struggling economy, coupled with instability and insecurity, have pushed many to seek a better life outside of Iran, seeking refuge in Europe, the US, and beyond. For a brief period Iranian asylum seekers had also been arriving in large numbers via perilous boat journeys to my home country, arriving on Australia’s north coast from ports in Indonesia. Boat arrivals in Australia are presently not allowed to stay in the country and are shipped off to the small islands of Naru and Manus for deportation or relocation to third countries, most recently Cambodia.

For all the genuine pride in their country people showed me, there were just as many stories from people hoping to leave, by any means possible.

From a taxi driver who showed myself and some other travelers photos of his lacerated back after he was given lashes for drinking home made beer, to an older man who brought himself to tears talking of his beloved brother, shot by the police for translating books into English a decade earlier, it was clear that many living in Iran have extremely good reasons to search for a better life elsewhere.

Below is a young girl and her mother leaning over the graves of some of those who lost their lives fighting during the 1979 revolution.

Yet from a traveler’s perspective the country is incredible.

Everything is cheap and the standard of hotels and food is generally pretty good. Mercifully, moving forests of selfie sticks are nowhere to be found. Well-known spots were busy at times, but never so much as to feel over crowded. Time will tell how long this will continue to be the case.

Below is Naqsh-e Rustam, an ancient necropolis with an impressive group of ancient rock reliefs cut and carved into the cliff. The oldest relief dates back to around 1,000 BC.

Below are two stone bulls flanking the north side of the Throne Hall at the UNESCO world Heritage site of Persepolis. Literally translating to “city of Persians,” the city Persepolis was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire, from around 550–330 BC.

Near Yazd are the ancient Zoroastrian ‘Towers of Silence.’ The Zoroastrians ‘purified’ their dead by exposing the bodies to the elements and to birds of prey, on top of these flat-topped towers, called dakhmas.

While in the city of Isfahan, I visited the beautiful Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque. Along with the Naghsh-e Jahan Square on which it borders, the mosque is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Early mornings see brilliant rays of light illuminate the intricate tile work of the building.

Also in Isfahan is Vank Cathederal, established by Armenian deportees settled by Shah Abbas I after the Ottoman War of 1603–1605. Today, this building remains one of the few Christian places of worship in Iran, and has many beautiful, fading murals within its interior.

One of the most interesting areas I explored during my visit was the southern region of the country, particularly the small islands and towns along the Persian Gulf coast. Thanks to the region’s colonial history as both a slave trading port and a stop on ancient trading routes, the area is home to the most ethnically diverse people in the country.

One morning I shared a simple breakfast of fruit and tea with the woman below, and afterwards she was happy for me to take her picture.

The capital city of this region is called Bandar Abbas, and is a major port for smuggled goods coming from Dubai and Oman. It is home to the Bandari ethnic group, which literally translates as ‘people of the port’.

The locals here dress colourfully and still practice many customs that differ somewhat from the rest of the country. For me, it was the potential for some colour and a break from the dark chador worn throughout much of Iran, that made it so appealing to visit.

Early one evening in Bandar Abbas, I paused alongside a large crowd gathered to watch a sideshow, a common sight in the region.

Below is a group of young men working to fix an Iranian built Paykan Taxi. When I returned to the city a week later, the men were still working on the cab, seemingly no closer to getting it moving.

Taking a short drive from the city of Bandar Abbas I arrived at the small town of Minab, seen below, where the people from around this vast area gather each week to sell their wares at the famous ‘Panjshambe Bazar’.

The striking coloured masks worn by the women of this region are said to have originated at a time when the Portuguese colonists would take the prettiest girls as slaves, and the masks would help to shield young girls from unwanted attention. I learned that each town in the region has its own signature variation of mask, varying in colour and construction.

The Panjshambe Bazar was a fascinating glimpse into the lives of the different cultures and people who call this area home. While there were large sections of the town dedicated to selling ubiquitous imported goods, there was still much to see that wouldn’t have changed much since Marco Polo made a visit — from the bustling livestock market, to the vendors selling colourful fabrics and homegrown produce.

For a fully grown, healthy goat, the prices seemed to hover around the 40 USD mark, a large sum of money for Iranians struggling in an economy crippled by sanctions and high inflation.

Below is a masked woman smoking tobacco from a waterpipe, or nargeela in Persian. This practice is banned for women throughout Iran in public places, but it remains popular amongst vendors at the market in Minab, who can often be found discreetly puffing away.

From tiny Minab I worked my way around to explore two rocky and arid islands just off the coast in the Persian Gulf, called Qeshm and Hormuz. On Hormuz, due to the severe lack of fresh water, Iranian engineers have constructed a water pipeline from the mainland.

Both islands are home to some of the oldest settlements in the Middle East, with a number of historic mosques and shrines, and I explored the crumbling ruins of ancient Portuguese castles and forts.

In 1507 the Portuguese conqueror Afonso de Albuquerque attacked the island of Hormuz, and it became a part of the Portuguese Empire. For over a hundred years, the Portuguese occupied the island, also capturing other islands and ports nearby, including the island of Qeshm. Their rule came to an end in 1622 when the Safavid king, Abbas I, conquered the Portuguese territories, forcing them to leave the Persian Gulf. Below you see remains of a chapel at the Portuguese fort on the island of Hormuz.

During 2009 Iran and Portugal prepared joint plans to restore historical sites in this region, however, little work seems to have taken place since then. These two young girls were passing through the ruins of the ancient Portuguese castle in the village of Laft, on Qeshm island.

Qeshm island is also home to large reserves of natural gas and a massive military presence. In early 2012, an underground military facility was established, designed to house Iran’s Ghadir-Nahang class submarines. The week after my visit a mock US warship was sunk just off the coast here by missiles fired from the main base in the east of the island.

Military service is mandatory for Iranian men. Except for special exemption cases, men not completing their service are unable to apply for a driving license, passport, or leave the country without permission.

Today the communities living on the islands of Hormuz and Qeshm are small, and in addition to natural gas exploration and production, fishing is one of the primary occupations for inhabitants of these islands.

Above you see a partially constructed Iranian lenge on Qeshm island, which is a traditional style of fishing vessel made of wood.

Above: (Left) A colourfully adorned house on Hormuz with a poster of Iran’s past and present. (Right) Women on Qeshm Island

My hope is that the images shared in this story show a bit of both sides of Iran, as it is certainly a place that defies preconceptions.

Today, despite its beauty, rich history, and welcoming people, there is still a long way to go before it becomes a country where all of its people can feel safe, secure, and able to provide a better life for their children

Above: Morning light shines across the spectacular Nasīr al-Mulk Mosque in the city of Shiraz. The exterior of the building was completed in 1888.

BROOK MITCHELL

Brook Mitchell is a photographer and writer based in Sydney, Australia. His work ranges from local and national press for Getty Images and The Sydney Morning Herald, to longer form editorial articles and photo essays from around the globe.

Finding Family On the Go in Nepal

Foregoing proper family time is one of the biggest sacrifices I make as a professional traveler. It is too easy to go “off the grid” and think that every one just understands a vagabond lifestyle. Far too often it is just assumed that the traveler in the family is out of the country and the conversations go from, “Hey let's grab lunch!” to “When’s the next trip, how long are you gone and why are you leaving me again?” Always absent from the birthday parties, weddings and the impromptu Sunday morning coffee chats with the grandparents. Absent from the little one’s baseball games, grandma’s chemotherapy appointments and the family BBQ’s at my parent's pool. Absent becomes an all too common trend.

When looking at my niece and younger cousins, I think about the close bond I made with my favorite aunt as a kid because of the trips to Chuck E. Cheese’s, the movie nights and always knowing without a doubt that she would be in the crowd at every baseball game. Will I be that awesome uncle or someone for them? I notice that my parents are donning a few more greys these days and my grandparents are having run-ins with illnesses more often. Should I be home reigniting the Sunday family dinner tradition that was so strong throughout my childhood? These questions run through my mind regularly and fill me with a small sense of guilt.

Sometimes, I would do anything for a one way ticket home to surround myself with family and bask in the cheap rent prices of the Midwest. However, that is not in the cards right now and won’t be for a long time. Until then, I will forever appreciate Southwest Airlines for the cheap flights (and 2 free checked bags!) from NYC to Kansas City that I frequent 2-3 times a year. I highly cherish this valuable family time and am incredibly thankful for it.

I finally turned a corner on not feeling guilty for being gone on my most recent trip to Nepal. As a part of my job with buildOn, I get the privilege of living with different host families twelve times a year around the globe. As a trek coordinator, I manage teams of Bronx high school students and volunteers traveling to a community to break ground and construct a primary school. This experience is called trek, and yes, you can get involved. My host families have all been amazing.

However, my latest host family in Nepal was unlike any others I had stayed with. They left me feeling full of so much warm love and happiness that I didn’t want to leave. For 9 nights, I became part of the Sunar family in the Bhagatpur Village. Despite our language barrier, our differing skin tones and our unique understandings of the world, I truly knew I had found long lost family members that I just had not had the opportunity to meet yet.

Every night when I wandered back into my room of their tiny concrete home, I was exhausted. It would have been very easy for me to take my bucket shower, eat my dinner and go to sleep without much interaction. Instead, no matter what time I rolled in, my three host sisters, Joti, Alicia and Aribica were eagerly waiting to greet me with the biggest smile and a “Namaste brother!” I couldn’t help but smile and quickly put my things down to join them for dinner.

Dinner time in Nepal is all about sharing family time. We would all surround a little fire stove while sitting on straw mats on the dirt floor and take our turns washing our hands. My host grandmother proudly served us heaps and heaps of rice, lentils, potatoes and vegetables that she had been preparing for hours in her primitive kitchen. My family never served themselves first and always made sure that I was so full that I could barely move because not taking seconds is simply not an option in Nepalese culture. Most nights we would practice our languages, and without fail they would burst out laughing every time I butchered a Nepali word or phrase. One night, I gave them a 100 piece jigsaw puzzle with the photo of two elephants on it. To my surprise, they had never seen a puzzle and were very confused as to what it’s purpose was. For 45 minutes, we sat and focused on putting that puzzle together and I happily observed as their problem solving wheels turned every time they placed each piece. Most people would have given up, but all 7 family members huddled around to tackle this puzzle. This reminded me of the days spent piecing puzzles together with my mom as a kid and even though I was filled with nostalgia, I knew how proud she would be to see me teaching them our favorite past time.

Piecing together that puzzle was just one of many activities we shared in that small little kitchen. Thanks to my great friends at LuMee, we took hundreds of illuminated selfies and videos. My host sisters sat one night and artistically colored in my henna tattoos with markers I had brought them. We talked about their religion, their family and how education is important for everyone. We laughed and laughed and laughed. We were family. No matter how stressful the day, every night when I went to sleep underneath my mosquito net on my bed that doubled as a table, I couldn’t help but think about how much they have, despite lacking many modern day luxuries that so many of us prioritize. They have family, they have love and they have community - is that not what we are all searching for?

When it was time to finally leave my family in Bhagatpur, I was filled with the usual sadness I feel at the end of my treks because of the unknowing of whether or not I will ever see my host families again. The reality is that I very likely will not. As I walked to the bus with both little sisters palms in my hands and my entire family following behind, I looked at them and grinned and said, “I love you family” and through their tears they said, “Love you brother!” In that moment, I knew that my family has forever grown by seven members.

My family means the world to me. If I didn’t travel that world, I would never find my family members like the Sunar’s, and that to me is more than enough reason to keep traveling. My family will forever grow.

#lucasonthego

What Is CATALYST?

Check out the launch video for CATALYST.cm, a platform for social action and travel.

NAMIBIA: Colors of a Country

Namibia is a land of contrasts and extremes. Situated between the Namib and the Kalahari deserts, Namibia gets less rain than any other country in sub-Saharan Africa. Namibia’s coastal desert is one of the planet’s oldest, with powerful offshore winds sculpting the highest sand dunes in the world, in some places rising more than 1,000 feet.

Water — or more to the point, its absence — defines life in Namibia.

Hot and arid in the interior, Namibia’s coast is surprisingly cool and moist, the product of the cold Atlantic colliding with Africa’s warm and dry southern tip. Seals and sea birds come by the thousands to congregate in this narrow temperate zone.

In the rest of the country, only where there is water is there life. Here is my vision of this untouched and primal land, with its towering red sand dunes, vast deserts, and wild animals struggling to survive.

KOLMANSKOP

Kolmanskop is a deserted German mining settlement located in Namibia. The town was abandoned in the 1950s, and the desert has been reclaiming it ever since, creating an interesting mix of colorful painted walls and sweeping sand dunes engulfing entire rooms.

QUIVER TREE FOREST

The Quiver Tree Forest, near Keetmanshoop, contains a collection of the so-called “quiver trees” which aren’t really trees at all, but rather a species of aloe, a flowering succulent plant.

NAMIB-NAUKLUFT NATIONAL PARK

Namib-Naukluft National Park preserves part of the extensive Namib Desert. The most famous area of the park is called Sossusvlei, which contains the tallest sand dunes in the world, rising more than 1,000 feet above the desert floor. Oxidization of iron in the sand gives them a reddish-orange color, which becomes especially intense when bathed in the warm light of sunrise and sunset.

One of the most stunning places in Sossusvlei is known as Deadvlei (which means “dead marsh”). The area used to be wet and covered in trees, but 600 or 700 years ago the water dried and the trees died, their eerie skeletons preserved by the dry air.

ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK

Etosha National Park is a beautiful national park in northwestern Namibia, known for its abundance of large game animals, including elephant, lion, rhino, giraffe, cheetah, zebra, and many more. What amazes me most about Etosha is the clear, strong light at sunrise and sunset, bathing animals and landscapes in warm color.

IAN PLANT

World-renowned professional photographer, writer, and adventurer Ian Plant is a frequent contributor to and blogger for Outdoor Photographer Magazine, a Contributing Editor to Popular Photography Magazine, a monthly columnist for Landscape Photography Magazine, and a Tamron Image Master. Ian is also the author of numerous books and instructional videos. See more of his work at www.ianplant.com

ITALY: Rainbow Warriors

The idea to sleep in a hammock suspended hundreds of feet above the ground in such an incredible place was born back in 2012 at the very first Highline Meeting held on Monte Piana, a peak of 2.324 meters.

The event was founded by Alessandro d‘Emilia and Armin Holzer, two highliners who wanted to share the spectacular scenery of Monte Piana (Misurina) in the Dolomites, giving professionals and enthusiasts from all over the world the chance to slackline between mountain peaks, hang out in hammocks strung high in the sky, and meet like-minded people.

This year the place where d‘Emilia, Holzer and action coordinator Igor Scotland from Ticket to the Moon hammocks built their set up was memorable not only for its natural beauty but for its particular historical importance. One century ago, fierce battles broke out in the shadow of Monte Piana in the Italian Dolomites as WWI began, and today the area is an open air museum to honor the memory of the 18.000 young soldiers who lost their lives here. The seven kilometers of trenches are still visible.