Reenactments of the Civil War and World War II help educate the public about important historical events, but they also risk glorifying some of history’s most evil societies.

Impersonating a Nazi soldier. virtualwayfarer. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Spring, 1944. The American G.I. hid with the Russian partisans, waiting to ambush the Nazi patrol. The Allies were making short work of Hitler’s war machine on both the eastern and western fronts. Still, these soldiers learned that war involves a lot of waiting around. They scoured the forest for the optimal position for attack. Finding an advantage was crucial when fighting the Waffen SS, the most elite Nazi soldiers. When the first round sounded out, the American hid in the underbrush. He managed one kill from his position. When he started moving, the ambusher became the ambushed. Nazis opened fire and shot him down. He lied gasping on the battlefield.

A while later, he got up and joined the other fallen soldiers, Nazis and partisans alike. They gathered on a dirt path to trade notes on what could have been done to save their lives. Later that night, they enjoyed a hog roast.

His name is Joe Bish, and he’s a reporter for VICE News. For one day, he partook in a controversial pastime with a group of enthusiastic British history buffs: reenacting World War II battles. It seems innocuous enough for a part-time hobby, yet concerns arise when half of them don Nazi uniforms for the sake of historical accuracy.

Nazi reenactors on the move. jcubic. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Such hardcore history buffs brought controversy to an English village in 2018 when a Jewish visitor spotted reenactors moseying through the streets in Nazi uniforms. National media, from The Sun to The Guardian, relayed the visitor’s discomfort and disbelief. Organizers defended the public utility of reenacting history, but reenactors were nonetheless on the defensive. The situation called into question what was thought to be an innocuous, even publicly educational, hobby.

Such controversies are not exclusively British. In 2010, Rich Iott lost a Congressional election in Ohio after The Atlantic unearthed two pictures of him dressed as a Waffen SS soldier. A favorite among Tea Party candidates, Iott defended his reenactments as a harmless pastime and a father-son bonding experience; he also participated in reenactments as a Union soldier in the Civil War and as an American soldier in both World Wars. Predictably, his statements did little to stymie public outrage. Jewish groups denounced his reenactments, and even fellow Republicans distanced themselves from him. It goes without saying that few people could elect a man they saw dressed as a Nazi soldier.

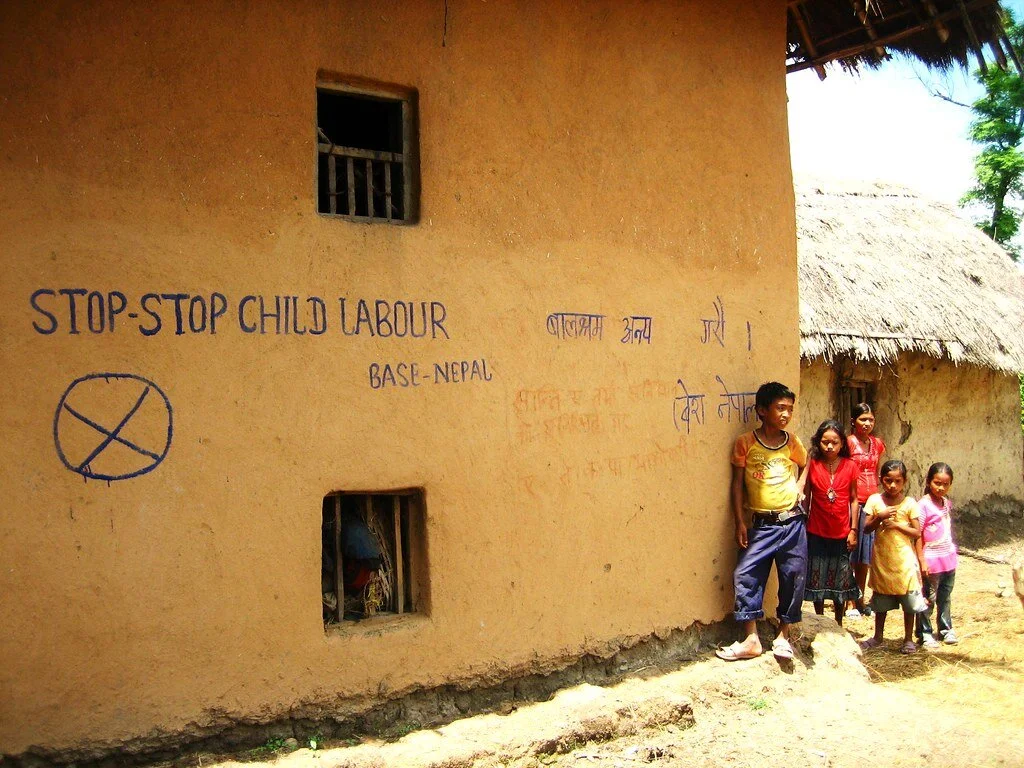

Recreating war or perpetuating racism? Matthew Straubmuller. CC BY 2.0.

But these controversies are also not just Nazi-related. As debate rages in the United States about the legacy of Confederate monuments, many call into question the need for recreations of Civil War battles. Although many participants are just outdoorsy historians, some blur the line between embodying history and living out a fantasy. The Sons of Confederate Veterans have 30,000 members, many of whom play their Confederate ancestors in historical reenactments. They market themselves as a “non-political heritage organization.” Their website calls the Civil War the “War for Southern Independence” and defines their mission as “the vindication of the cause for which we [the Confederates] fought.” One of their slogans is to “Make Dixie Great Again.” In a multicultural and diverse country, their participation makes reenactments difficult to justify.

Confederate symbols worryingly overlap with Nazi ones in many international contexts,especially in Germany. Swastikas are banned there, but Confederate flags appeared in great numbers at anti-lockdown demonstrations. To Germans unfamiliar with its historical context, the flag symbolizes rebelliousness. The Confederate flag also appeared at the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

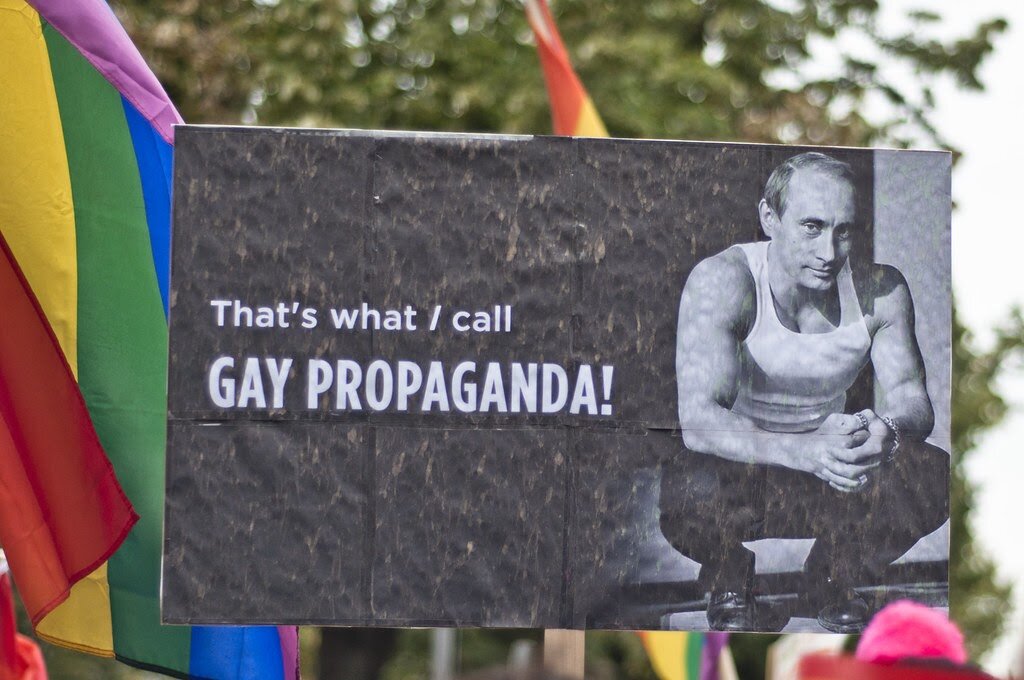

The Nazi’s racial heirarchy. Joelk75. CC BY 2.0.

Anti-Blackness appears elsewhere in German culture. Gone with the Wind was a beloved film and smash hit; the book on which it was based sold 300,000 copies in Germany alone. The film romanticized the antebellum South by chronicling dainty balls and gentlemanly courtships while ignoring the plight of the enslaved. Although the film was banned by the Nazis, it remained an influential cultural artifact. Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Propaganda, wrote of the film in his diary, “We will follow this example.”

Riders of Berlin’s subway encounter Germany’s disturbing nostalgia for the American antebellum South on a daily basis at the station named “Onkel Toms Hutte,” or Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The name comes from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s incendiary anti-slavery novel of 1852. Though advocating for the abolition of slavery, the book spread the myth of the “happy slave” among American and international audiences; the book sold widely in Germany. In the early 20th century, the book was cited to justify the racial hierarchies of German colonialism.

Given the political weight of Confederate flags and Nazi uniforms, historical reenactments remain an embattled practice. COVID-19 caused countless reenactors to forgo battles for the good of public health. Now, many seem reluctant to bring them back. War reenactments serve a valuable function in educating the public about the not-too-distant past, but for some, they don’t tell historic stories—They glorify them. It seems that reenactors, no matter how hard they try to escape into the past, remain bogged down in the present.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.