Mexican and Mexican American “Pachuco” culture formed in the late 19th century along the the US-Mexico border. Zoot suits and lowriding cars are popular symbols, but the unique look singled out Pachucos as targets of racial discrimination, such as the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles in 1943.

Read MoreThe Tapati festival on Easter Island is a colorful celebration of Rapa Nui heritage. It is enjoyed through traditions such as the singing performance and flower crowns seen here. Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Easter Island’s Tapati Festival: A Celebration of Rapa Nui Tradition

When most think of Easter Island, located nearly 2,200 miles off the coast of mainland Chile, the first thought that comes to mind is, “How did those heads get there?” While the giant stone structures known as moai are quite fascinating, they are only one of the island’s impressive features. With its westernized name, it is easy to forget that the island, known as “Rapa Nui” to its natives, has been populated for centuries. The Tapati festival was born to celebrate that heritage.

The Tapati festival began in the 1970s as a way to educate the world about Rapa Nui’s people and their customs. More importantly, it is a way to reconnect children on the island with their heritage and identity. In the last few years it has grown in popularity, and it is featured on many tours to the island. This year it was rescheduled due to the pandemic, but the celebration is set to happen early next year.

The two-week festival consists of music, dance and ancestral sporting events like swimming, canoeing and horse racing. The competitions take place between two clans in the spirit of the island’s Polynesian history. The events take place all over the island from day to night with the people of Rapa Nui emphasizing their heritage through face painting and dress. Each group also nominates a woman who receives points from the winners of the physical competitions, and the two compete to become the queen of Tapati at the end of the celebration.

Rano Raraku, a volcanic crater on Easter Island. Iko. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

What Tapati is most noted for is the triathlon, the Taua Rapa Nui. This three-pronged competition is held at the Rano Raraku, a massive volcanic crater that many of Easter Island’s moai sculptures were carved from. The events that make up Taua Rapa Nui are the Pora, the Aka Venga and the Vaka Ama.

The Pora is a canoe race in which solo competitors in traditional outfits and body paint paddle across the crater lake on reed boats. Upon reaching the other side, they immediately transition into the Aka Venga, a running race made more difficult by the need for contestants to carry two banana bunches on their shoulders. This event is notorious for taking out racers.

Competitors practicing for the Pora. Alvaro Valenzuela. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Another impressive event is the Haka Pei, where dozens of men cloaked in only body paint and a cloth race down the steepest hill on the island in sleds made of banana tree trunks.

Beyond physical competitions, there are many ancestral skills competitions like cloth making from mahute tree bark, stone and wood carving, and clothing designing. Another event is a cooking competition where women of the island face off with their creations of traditional Rapa Nui dishes. Additionally, there is an agricultural showcase in which farmers compete to see who has the biggest and heaviest products. As it is a two-week event, countless different cultural traditions are highlighted throughout the festival.

For visitors, the grand celebration of Rapa Nui and its people is a valuable way to respectfully learn about and appreciate islanders’ traditions. It is a culturally immersive experience, and the people on the island know that their heritage is worthy of recognition. Often, island cultures get isolated from global conversations as the beautiful landscapes distract from traditions. Festivals like the Tapati ensure that Rapa Nui’s residents are never forgotten.

Renee Richardson

Renee is currently an English student at The University of Georgia. She lives in Ellijay, Georgia, a small mountain town in the middle of Appalachia. A passionate writer, she is inspired often by her hikes along the Appalachian trail and her efforts to fight for equality across all spectrums. She hopes to further her passion as a writer into a flourishing career that positively impacts others.

Indigenous Mexican Language isn’t Spoken– it’s Whistle

While Spanish is the official language of Mexico, its many Indigenous cultures still thrive and speak their own languages within their communities.

Read MoreThe Mexican Street Cart: A Culinary World on Wheels

Mexican street foods, like birria tacos and elote, have gained widespread attention on social media recently for their complex flavors and vivid colors. Some dishes have gone so viral that Americans are driving hours in search of truly authentic carts! Mexican street carts are essential to the people of Mexico, providing a convenient meal during a busy day, and more are popping up all over the United States as well.

Read More10 Nigerian Artists Redefining Africa’s Music Scene

From influencing the #EndSARS protests to confronting the commodification of African culture, these artists have unique approaches to their art.

DaVido performing. Wikimedia user Rasheedrasheed. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Nigerian musicians have been spreading their influence all over the world for the past few decades. Following in the footsteps of Fela Kuti, contemporary artists experiment with a plethora of genres, fine-tuning their style as they progress. Renowned artists such as Burna Boy, DaVido and Cruel Santino are the driving forces of the Afrobeats movement, which combines African subgenres, American hip-hop, and R&B. Here are 10 influential Nigerian musicians to listen to.

1. Tony Allen

Tony Allen. Pierre Priot. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Tony Allen is the father of the Afrobeat genre. Allen passed away in April 2020 after releasing his final album, “Rejoice,” in collaboration with the late South African jazz artist, Hugh Masekela. Allen’s polyrhythmic drumming complements Masekela’s trumpet in this riveting jazz album. From his earlier days of performing with Fela Kuti to his more recent collaborations with Skepta and Oumou Sangare, Allen has pioneered the combination of American jazz with African beats. After a career which explored a multitude of scenes in the music world, Allen falls back into his Afrobeat roots in his very last album.

2. Naira Marley

Rapper Naira Marley is a contentious figure in Nigeria. Marley is known as a founder of the genre Afro-bashment, a combination of Caribbean influences, American trap rap, West African beats and British rap. Naira Marley is known for his controversial beliefs and ideas; in “Am I a Yahoo Boy,” he offers an unabashed critique of the Nigerian government, higher education and social conservatism. His single “Koleyewon,” which was released in December 2020, is a fast-paced trap song in Yoruba.

3. DaVido

DaVido performing. Wikimedia user Rasheedrasheed. CC BY-SA 4.0.

American-born musician DaVido is a world-renowned Afrobeats artist who synthesizes elements of R&B, rap and Afropop to build up his discography. His heavily auto-tuned vocals and his simple audio production make up his signature sound. DaVido’s most recent album, “A Better Time,” featured Nicki Minaj, Chris Brown and Lil Baby. Despite its famous featured artists, the album’s first track, “FEM,” received the most attention globally. “FEM,” which means “shut up” in Nigerian slang, was labeled the anthem of the #EndSARS protests in Nigeria, which called for the dissolution of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad. Although the artist himself didn’t intend to express a politically charged message, he was nonetheless impassioned by his country’s fight against police brutality.

4. Cruel Santino

Up-and-coming musician Cruel Santino came to the world stage in 2019 with his debut album “Mandy & The Jungle.” Although he is one of the younger artists of the Nigerian music renaissance, Cruel Santino offers an impressive range of styles in his first album. The mellow, laid-back beat of “Sparky” contrasts with the country twang of “Diamonds / Where You Been.” His new single “End of The Wicked” showcases his maturation as a musician and an artist: the solemn piano is redeemed by a syncopated jungle beat, which accompanies his verbose rap.

5. Odunsi (The Engine)

Odunsi (The Engine) is a master of his craft. His discography is all-encompassing: church choirs and spoken word start off his 2018 album “Rare”; an orchestra plays over his verse in his greatest hit “Tipsy”; a vaporwave synth paints “Luv In a Mosh” blue. Odunsi (The Engine)’s album covers visually harmonize with his music. The ethereal blue moon in “Everything You Heard Is True,” which was released in May 2020, mirrors Odunsi’s experimentation with atonal melodies and distortions. On top of this hypnotic album, the musician released two singles in 2020: “Decided” and “Fuji 5000.” Both are dramatically different from each other; the only constant is Odunsi’s effortless flow.

6. Simi

Simi at NdaniTV. NdaniTV. CC BY 3.0.

Simi’s distinctly sweet voice is the honey that binds her music together. Less is more in her 2017 album “Simisola,” where her vocals and the acoustic guitar are the only elements that matter. The Nigerian singer started off as a gospel singer in 2008, but transformed her career in 2014 after the success of her singles “Tiff” and “E No Go Funny.” Simi released “Restless II” in 2020, which is a change of pace from her slow crooning. In an interview with OkayAfrica, the singer admits that, “This project is a risk as well, it’s even more of a risk because it’s R&B and Nigeria is not necessarily the biggest R&B market.” As Simi continues to dabble in hip-hop, she comes out with more powerful hits like “No Longer Beneficial” and “There for You.”

7. Niniola

Niniola. Wikimedia user Naijareview. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Often regarded as the “Queen of Afro-House,” Niniola is a global star who fights to find her footing as an empowered Yoruba woman. Niniola rose to fame from her 2017 hit “Maradona,” a seemingly light pop tune which dealt with the traumas of her upbringing. As a girl growing up in a polygamous household, Niniola experienced the double standards of a patriarchal family. Reckoning with her womanhood, Niniola recounts the experiences of a woman who is cheated on by her husband, woes which are usually kept secret. With an album and a couple of huge hits under her belt, Niniola comes back strong with her new album “Colours and Sounds,” which includes a refreshing take on reggae, pop and dancehall.

8. Burna Boy

Burna Boy’s album “Twice as Tall” covers a variety of topics, from how the artist grapples with the reality of colonialism to the frenzy of a night out. Burna Boy is a household name in the music industry, and this album attests to the singer’s mastery over songwriting and producing. In his song “Monsters You Made,” Burna Boy addresses Western imperialism and how its consequences are still felt today. His song “Alarm Clock” begins with voice recordings, opera and a saxophone, and quickly switches to an upbeat rap song.

9. Deto Black

Model and rapper Deto Black refuses to be labeled as an Afrobeats musician. The feminism and sex positivity of her music is obvious and brought to the forefront of her message as an “alté,” or alternative, artist. As a Lagos-based rapper who lived in the U.K. and the U.S. growing up, Deto Black navigates the different worlds by calling for gender equality in Nigeria.

10. Zlatan Ibile

Zlatan is a new Nigerian singer and dancer who found fame through his viral song “Zanku” (Legwork), which was accompanied by a famous dance. Since 2019, the singer has released three albums, started a record label, and released the successful single “Lagos Anthem.” “Lagos Anthem” is an energetic dance song with darker lyrics criticizing the government for its flawed policies.

These Nigerian musicians are beginning to impact American and British pop music. Although each of these individuals comes from a different discipline and background, they all have a commitment to experimenting in their craft. Some thrive in and renovate the Afrobeats movement, while others resist the umbrella term. The common ground between alté musician Deto Black’s tackling of gender inequality and DaVido’s propelling of the #EndSARS revolution is their commitment to the well-being of Nigeria.

Heather Lim

Heather recently earned her B.A. in Literatures in English from University of California, San Diego. She was editor of the Arts and Culture section of The Triton, a student-run newspaper. She plans on working in art criticism, which combines her love of visual art with her passion for journalism.

Honoring San Basilio de Palenque: The First Town Liberated from Slavery in the Americas

The story of San Basilio de Palenque is one of unparalleled strength, resistance and bravery.

River near San Basilio de Palenque. Fundacion Gabo. CC2.0

Roughly 30 miles away from the port city of Cartagena, Colombia, lies the small town of San Basilio de Palenque. Palenque has rich historical significance, as it was the first free African town in the Americas. The town was declared a “Place of National Character and Cultural Interest” by the Colombian government and a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity” by UNESCO in 2005.

History of San Basilio de Palenque

Town square in San Basilio de Palenque. Restrepo. CC2.0

San Basilio de Palenque was one of many walled forts, known as palenques, that were founded by those escaping slavery in colonial times. Founded in 1603 by Benkos Bioho and 36 other people, San Basilio is the only palenque remaining to this day and was successful due to its isolated location amid swamps and hills. Escaped slaves from Cartagena and surrounding regions would travel to San Basilio de Palenque in the hopes of seeking freedom. Against all odds, “palenqueros” formed their own army, language and support system to stay safe. The town was declared the first free town in the Americas in 1713, nearly 100 years before Colombia became independent from Spain.

Palenqueros in Colombia Today

Palenquera women in Colombia. Vest. CC2.0

The isolated nature of San Basilio de Palenque provides limited employment opportunities, which in turn causes the migration of many palenqueros to larger cities in search of work. On the streets of Cartagena, palenquero men are engaged in construction projects while palenquera women wearing brightly colored dresses sell fresh fruit and traditional sweets made of nuts, tropical fruits and panela (unrefined sugar). In a video from Great Big Story, the palenquera Everlinda Salgado Herrera discusses the historical and cultural significance of a sweet called alegria (meaning happiness in Spanish), which represents the joy palenqueros felt when they found freedom.

Although palenqueros are becoming integrated into Colombian society, they were initially met with discrimination, sometimes leading to feelings of resentment and denial over their cultural and racial identity. In the 1980s and ‘90s, a young generation of palenqueros advocated for a resurgence of palenquero culture, hoping to promote an appreciation of their rich heritage. Strong cultural pride among palenqueros continues to this day. Edwin Valdez Hernandez, a dance instructor at the Batata Dance and Music school in Palenque, states, "We defend our values with a shout. We are Black, and we are defending our culture."

Cultural Treasures of San Basilio de Palenque

Drummers in Palenque. Vest. CC2.0

Palenque is known worldwide for its unique language, music and culinary scene. One of Colombia’s 69 Indigenous languages, the palenquero language is only spoken in San Basilio de Palenque. Captives on European slave ships came from all parts of Africa speaking a variety of languages. As a colonizing strategy, people were purposely mixed together so they would not be able to communicate to plan an escape. Despite this, palenqueros created their own language, influenced by Castilian Spanish, Bantu, Portuguese and English.

The cuisine of San Basilio de Palenque is a delight for the taste buds. Some dishes include seafood rice, mote (a traditional Caribbean cheese), and fish cooked in a creamy coconut sauce with pigeon peas, cassava and panela sugar. Palenquero cooking continues to reach international heights, most notably when the book “Cocina Palenquera Para el Mundo” won first prize at the 2014 Gourmand Cookbook Awards in Beijing.

Music is an incredibly important part of palenque culture and throughout Colombia. Palenque music is joyful with sweeping rhythms and fast drum beats and is coupled with bright costumes and a seemingly endless stamina for dancing. Some of the many dance styles include chalusonga, paseo, champeta, entrompao and palenquero son. Travelers can learn about Palenque’s rich musical culture by attending the Drums and Cultural Expressions Festival held annually in October.

The town of Palenque is also known for its interesting methods of running society. Instead of a police presence, Palenque is organized into systems called ma-kuagro, where people have designated roles and watch over each other. The crime rate in the town is nearly nonexistent due to this sense of community among Palenqueros. Interestingly, palenque women’s hairstyles also have historical significance. In colonial times, women would braid intricate patterns in their hair that were used to create maps, store gold and transmit messages to help people reach freedom. A statue of Palenque founder Benkos Bioho breaking out of chains stands in the town center.

A place of redemption and perseverance, San Basilio de Palenque is a cornerstone of Black resistance in Latin America and a perfect destination for a socially conscious traveler. Confronting past historical truths and being willing to listen to others’ experiences helps shed light on modern social issues to hopefully make the world a brighter and better place.

Megan Gürer

is a Turkish-American student at Wellesley College in Massachusetts studying Biological Sciences. Passionate about environmental issues and learning about other cultures, she dreams of exploring the globe. In her free time, she enjoys cooking, singing, and composing music.

10 Mouthwatering Rice Dishes from Around the World

The world is filled with a variety of rice dishes.

Rice grains. Verch. CC2.0

No matter where you are in the world, rice is a much loved staple. First cultivated in China and spread through international trade and migration, every region has its own way of preparing rice with local spices and ingredients. Here is a sample of 10 unique and culturally significant rice dishes from around the world.

Morasa polo with tahdig. Moos. CC2.0

1. Morasa polo (jeweled rice): Iran

Morasa polo (jeweled rice in Farsi) is one of Iran’s most festive dishes, traditionally served at celebrations and weddings to bring “sweetness” to a married couple. The rice is topped with various types of fruits and nuts, each representing a desired jewel. For example, barberries represent rubies and pistachios represent emeralds. Each component of the rice is cooked separately in sugar to give the dish a little sweetness. No plate of rice in Iran is complete without tahdig (literally “bottom of the pot”), referring to the crispy layer of rice at the bottom of the pan. One of the most coveted and challenging techniques to master in Persian cuisine, tahdig can be made several ways by using ghee, saffron, potatoes and lavash bread to give that desired crunch.

Nasi tumpeng. Kenwrick. CC2.0

2. Nasi tumpeng: Indonesia

Nasi tumpeng is a traditional rice dish served at a selamatan, a traditional ceremony for special occasions such as birthdays and weddings. The dish consists of a tall rice cone in the center, usually yellow rice, which represents the mountains and volcanoes of Indonesia’s landscapes. According to tradition, the yellow mountain of rice refers to Mount Semeru, home of the hyang, the spirits of Indonesian ancestors and the Hindu gods. The dish is accompanied by seven side dishes with a balance of chicken, seafood, eggs and vegetables that represent the helping hands of God. Nowadays, the dish has been ingrained in Indonesia’s Muslim culture representing gratitude toward God.

Jollof rice. Secretlondon123. CC2.0

3. Jollof rice: West Africa

Widely enjoyed across Africa, there is perhaps no dish that has sparked such heated discussion over its origins as jollof. A staple in social gatherings and weddings across West Africa, the rice is cooked with tomatoes, onions and peppers with additional seasonings depending on the region. Historians credit the origin of jollof rice to the Senegambia region, with cultural exchange then spreading it across the rest of West Africa. However, Nigerians, Ghanaians and Senegalese all claim the origins of this dish and are eager to debate which version is better with online battles (#JollofWars) and cook-offs. The dish is also popular among the African diaspora in the American South. In fact, popular dishes such as jambalaya and gumbo are believed to have their origins in jollof rice.

Hamsili pilav. Vardar. CC2.0

4. Hamsili pilav: Turkey

Although there are many types of pilaf in Turkey and the Middle East, hamsili pilav is one of the most unique and visually striking versions, with layers of fish covering up rice. Hamsi, also known as European anchovies, are considered Turkey’s national fish and play a crucial role in the culture and cuisine of the Black Sea region. Many poems and songs have been written about hamsi and the small but mighty fish is used in a variety of dishes, from breads to pickles and even jam. Known to be a favorite of the sultans during the Ottoman Empire, hamsili pilav is still a favorite in Turkish homes, especially among the Laz people living in the northeastern regions of the country.

Khichdi. Tushar. Wikimedia Commons. CC4.0

5. Khichdi: Indian Subcontinent

This humble but delicious dish is heavily ingrained in South Asian food culture. Most commonly made with rice and moong dal (a type of legume), it is one of the first foods that babies eat in Hindu culture. Easily digestible and nutritious, khichdi is popular across South Asia, including in India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh. Many regional variations of khichdi exist, adding available ingredients such as vegetables, spices, dried fruits and coconut. The Bengali variation, known as khichuri, is a rather elaborate version, served with an array of vegetable dishes, fried fish and curries.

Maqluba. Homan. CC2.0.

6. Maqluba: Palestine

Often considered Palestine’s national dish, maqluba is enjoyed at least once a week by many Palestinian families. Meaning “upside down” in Arabic, the dish is cooked in one pot with layers of meat (chicken or lamb), vegetables (most commonly potato and eggplant) and rice. Once the dish is cooked, it is flipped over onto a plate and served.

Cooking traditional foods allows Palestinians to cherish their culture while empowering themselves and their families. The Noor Women’s Empowerment Group is run by 13 Palestinian women working to overcome social stigmas faced by women and disabled children in Aida refugee camp. The organization holds traditional Palestinian cooking classes as a way to generate income to support their families and give visitors an insight into Palestinian life and culture. The organization has garnered international attention and received a visit by celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain in 2013.

Arroz con pollo. Sea turtle. CC2.0

7. Arroz con pollo: Latin America and Spain

Translating as “rice with chicken,” this incredibly versatile rice dish is enjoyed across Latin America and Spain. The dish is thought to be connected to the Spanish paella and could have its origins from Arab influence in Spain as early as the 8th century. However, there is some debate as to whether the dish actually originated in Puerto Rico, as it is one of the island’s classic dishes. Arroz con pollo is seared chicken cooked with rice and vegetables, although seasonings vary from country to country across Latin America. For example, Mexican versions use chile, Colombian versions use a sofrito (blend of flavors including tomato and saffron) and Peruvian versions include cilantro and dark beer.

Ozoni. David Z. CC2.0

8. Ozoni: Japan

Ozoni (also spelled as zoni) is a soup that is eaten on the morning of New Year’s Day in Japan. The soup contains mochi cakes, either round or square-shaped, a clear dashi broth (made of dried kelp and bonito flakes) and other ingredients depending on the region. In areas closer to the water, seafood is added to the broth while more vegetables are used in inland areas. All ingredients have a special meaning that guarantees luck for the upcoming year. As mochi is stretchable, it represents longevity. Local produce is added for a bountiful harvest in the new year.

Wild rice. Emily. CC2.0.

9. Wild rice: North America

Considered to actually be an “aquatic grass seed,” wild rice has a higher nutritional value than regular rice. Wild rice is a staple of the Ojibwe people of southern Canada and the United States’ northern Midwest. The month of September was called “ricing moon”, when the Ojibwe left their homes to begin the weeklong process of harvesting the rice. Wild rice was a popular commodity at trading posts and was used to feed canoers transporting fur to and from the posts. The Ojibwe people would wait near rice fields to hunt birds, as ducks and geese use wild rice as a food source.

Rice and beans. The Marmot. CC2.0

10. Rice and beans: widely consumed across Latin America and Africa

Rice and beans is a staple in many Latin American and African countries and has become a pivotal part of their cuisines. Nutritious and filling, rice and beans have been a pairing in Latin America for thousands of years, known as the “matrimonio” or marriage in Central America. The types of beans and the preparation of the dish varies from country to country. For example, pinto beans are common in Mexico, fava beans are popular in Peru and black beans are a staple in Brazil and Cuba. Kidney beans and black-eyed peas are widely enjoyed across West Africa and the rest of the continent as well as in the American South. In Jamaica and other parts of the Caribbean, rice and pigeon or field peas are quite popular, while the rice is cooked in coconut milk.

From Iran to North America, the preparation of rice differs vastly. Despite many differences, food is something that brings the world together and fosters an appreciation of Earth’s incredible cultural diversity.

Megan Gürer

Megan is a Turkish-American student at Wellesley College in Massachusetts studying Biological Sciences. Passionate about environmental issues and learning about other cultures, she dreams of exploring the globe. In her free time, she enjoys cooking, singing, and composing music.

NOW IS THE TIME: Totem Poles and the Haida Spirit

When internationally renowned Haida carver Robert Davidson was only 22 years old, he carved the first new totem pole on British Columbia’s Haida Gwaii in almost a century. On the 50th anniversary of the pole’s raising, Haida filmmaker Christopher Auchter steps easily through history to revisit that day in August 1969, when the entire village of Old Massett gathered to celebrate the event that would signal the rebirth of the Haida spirit.

10 Places to Honor Black History and Culture

Through artwork, literature, music and history, these institutions amplify Black voices and address race relations in America.

George Floyd protests in Charlotte, North Carolina. Clay Banks. Unsplash.

Amid global protests against racial injustice, a growing number of people are educating themselves on systemic racism and white privilege.

1. Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park - Atlanta, Georgia

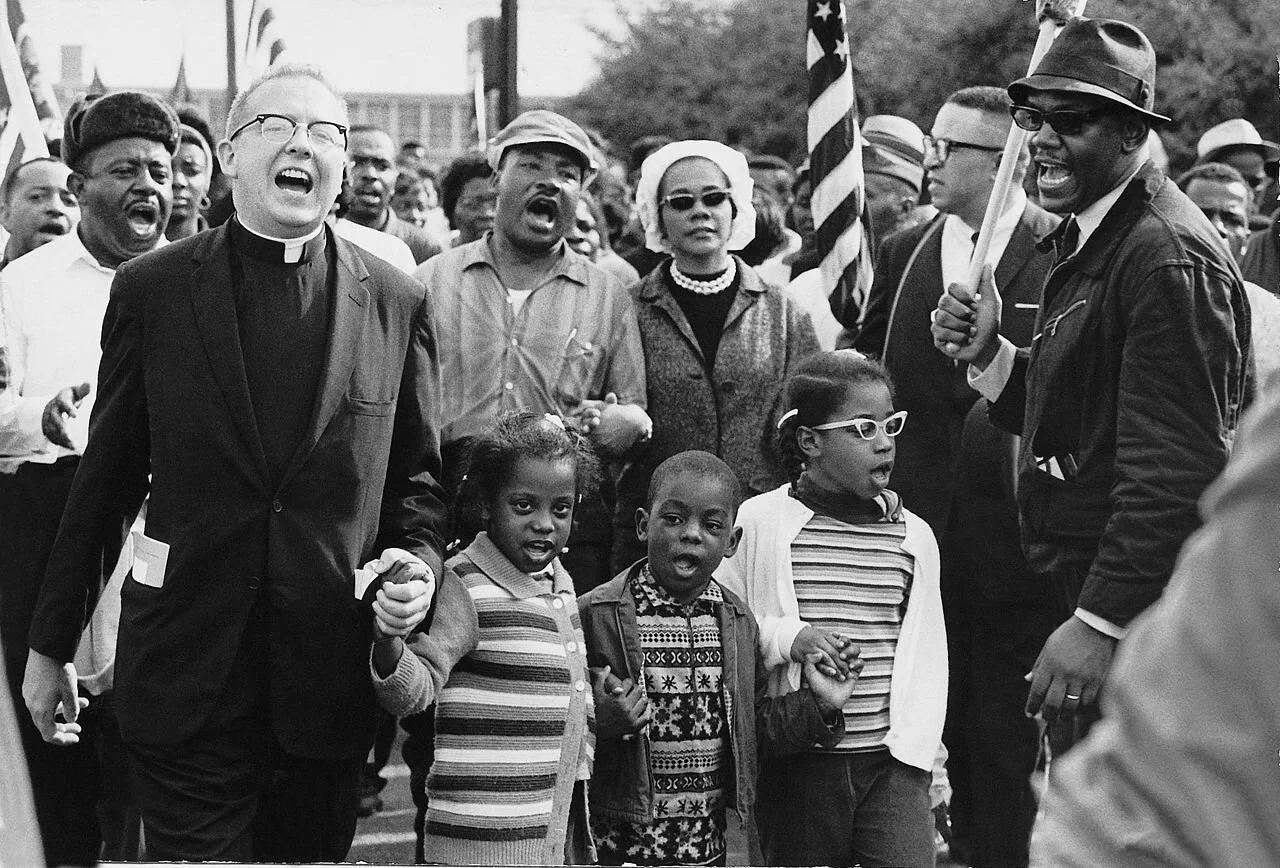

Martin Luther King Jr. locating civil rights protests. Thomas Hawk. CC BY-NC 2.0

Located in one of Atlanta’s historic districts, the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park honors the activist who strove for racial equality. The site includes a museum chronicling the American civil rights movement, as well as Dr. King’s childhood home, garden and gravesite. With 185 varieties of roses, the “I Have a Dream” World Peace Rose Garden promotes peace between diverse world communities. Each year, students from the greater Atlanta area write poems that express the ideals of MLK, such as using civil disobedience to reach seemingly impossible goals. These “Inspirational Messages of Peace” are exhibited among the flowers and are read by thousands of visitors each year. Directly across the street is the final resting place of Dr. King and Coretta Scott King, his wife, surrounded by a reflection pool.

Until his assassination in 1968, King preached at Ebenezer Baptist Church, known as “America’s Freedom Church.” The church has continued to serve the Atlanta community since his death, vowing to “feed the poor, liberate the oppressed, welcome the stranger, clothe the naked and visit those who are sick or imprisoned.” While sitting in the pews, visitors hear prerecorded sermons and speeches from Martin Luther King Jr. Most recently, the funeral of Rayshard Brooks, a Black man fatally shot by police, was held at the church, with hundreds of prominent pastors, elected officials and activists in attendance.

2. National Museum of African American History and Culture - Washington, D.C.

A student at the NMAAHC uses an interactive learning tool. U.S. Department of Education. CC BY 2.0

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is the only museum devoted exclusively to African American life, history and culture. In the words of Lonnie Bunch III, founding director of the NMAAHC, “The African American experience is the lens through which we understand what it is to be an American.” From slavery to the civil rights movement, the museum aims to preserve and document Black experiences in America. With the launch of the Many Lenses initiative, students will gain a greater understanding of African American history by studying museum artifacts and discussing cultural perspectives alongside scholars, curators and community educators. Through the Talking About Race program, the museum provides tools and guidance to empower people of color and inspire conversations about racial injustice.

3. Black Writers Museum - Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Langston Hughes, a famous writer featured at the BWM, signs autographs. Washington Area Spark. CC BY-NC 2.0

Built in 1803, the historic Vernon House includes the Black Writers Museum (BWM), the first museum in the country to exhibit classic and contemporary Black literature. The BWM celebrates Black authors, like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, who documented the resilience and resistance of African Americans throughout history. Supreme D. Dow, founder and executive director of the Black Writers Museum, noted, “There was a time in American history when Black people were denied the human right to read or write. But, because of the innate drive to satisfy the unquenchable thirst for self determination, our ancestors taught themselves how to read and write in righteous defiance of the law, and in the face of fatal repercussions.” Through books, newspapers, journals and magazines, the museum honors the Black narrators of history. The BWM also strives to inspire future African American authors with community activities like poetry readings, cultural arts festivals and book signings.

4. Tubman Museum - Macon, Georgia

Artwork depicting Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad. UGArdener. CC BY-NC 2.0

Named after Harriet Tubman, the “Black Moses” who led hundreds of slaves to freedom, the Tubman Museum has become a key educational and cultural center for the entire American Southeast. Through artwork and artifacts, the main exhibits recount the struggles and triumphs of Tubman, a former slave, abolitionist and spy. The “From the Minds of African Americans” Gallery displays inventions from Black inventors, scientists and entrepreneurs, such as Madam C.J. Walker and George Washington Carver. The Tubman Museum also actively contributes to the Macon, Georgia, community. The Arts & History Outreach program takes Black history beyond museum walls. Local African American artists and teachers bring museum resources into the classroom, promoting hands-on learning. Due to COVID-19, the museum recently launched a distance learning program to provide people at home with a deeper understanding of the African American experience.

5. Museum of the African Diaspora - San Francisco, California

Contemporary art by Kehinde Wiley exhibited at the MoAD. Garret Ziegler. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), a contemporary art museum, celebrates Black culture from the perspective of African diaspora. Focused exclusively on African migration throughout history, the museum presents artwork, photography and artifacts related to the themes of origin, movement, adaptation and transformation. Currently, MoAD is featuring various exhibitions from emerging artists that explore ancestral memory and Black visibility. As active members of the San Francisco community, museum curators offer various programs like public film screenings, artist talks and musical performances. In response to worldwide protests, the museum created a guide with resources to support Black Americans, as well as a video series that promotes community resilience. Monetta White, MoAD’s executive director, announced, “Now more than ever, we affirm that Museums are Not Neutral. As humanitarian educators and forums for conversation, museums are a space to confront some of the most uncomfortable conversations in human history.”

6. National Museum of African American Music - Nashville, Tennessee

Jimi Hendrix, a featured musician at the NMAAM. Clausule. Public Domain.

Scheduled to open its doors for the first time on Sept. 5, the National Museum of African American Music (NMAAM) will be the first museum in the world to showcase African American influence on various genres of music, such as classical, country, jazz and hip-hop. NMAAM will integrate history and interactive technology to share music through the lens of Black Americans. “African American music has long been a reflection of American culture. Additionally, African American musicians often used their art as a ‘safe’ way to express the way they felt about the turbulent times our country faced,” said Kim Johnson, director of programs at the museum. NMAAM will also support the Nashville community through various outreach programs. From Nothing to Something explores the music that early African Americans created using tools like spoons, banjos, cigar box guitars and washtub basins. Children receive their own instruments, learning how simple resources influenced future music genres. Another program, Music Legends and Heroes, promotes leadership, teamwork and creativity in young adults. Students work together to produce a musical showcase in honor of Black musicians. In 2015, student guitarists paid tribute to Jimi Hendrix, the rock icon. “This opportunity gave them a real-life connection to an artist they had only seen in their textbooks or online,” said Hope Hall, librarian at the Nashville School of the Arts.

7. The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration - Montgomery, Alabama

Exterior of the Legacy Museum. Sonia Kapadia. CC BY-SA 4.0

The Legacy Museum is located in a former slave auction warehouse, where thousands of Black people were trafficked during the domestic slave trade. The museum employs unique technology to portray the enslavement of African Americans, the evolution of racial terror lynchings, legalized racial segregation and racial hierarchy in America. Visitors encounter replicas of slave pens and hear first-person accounts of enslaved people, along with looking at photographs and videos from the Jim Crow laws, which segregated Black Americans until 1965. The Legacy Museum also explores contemporary issues of inequality, like mass incarceration and police violence. As part of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the museum is committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, with proceeds going toward marginalized communities. “Our hope is that by telling the history of the African American experience in this country, we expose the narratives that have allowed us to tolerate suffering and injustice among people of color,” says Sia Sanneh, member of EJI.

8. African American Military History Museum - Hattiesburg, Mississippi

Circa 1942, the Tuskegee Airmen pose in front of their aircraft. Signaleer. Public Domain.

The African American Military History Museum educates the public about African American contributions to the United States’ military. During World War II, the building functioned as a segregated club for African American soldiers. Transformed in 2009, the museum now commemorates the courage and patriotism of Black soldiers, who have served in every American conflict since the Revolutionary War. Artifacts, photographs and medals tell the story of how African Americans overcame racial boundaries to serve their country. For instance, the World War II exhibit features the Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American soldiers to successfully enter the Army Air Corps.

9. National Voting Rights Museum and Institute - Selma, Alabama

The 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery for the right to vote. Abernathy Family. Public Domain.

In the historic district of Selma, Alabama, the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute honors the movement to end voter discrimination. With memorabilia and documentation, the museum illustrates the struggle of Black Americans to obtain voting rights. In 1965, nearly 600 civil rights marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, hoping to reach Montgomery. However, the day became known as “Bloody Sunday” as local law enforcement attacked peaceful protesters with clubs and tear gas. While the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed voting practices that disenfranchised African Americans, many believe voter suppression still exists through strict photo ID laws for voters, a failure to provide bilingual ballots, and ex-felon disenfranchisement laws. By educating the public, the museum hopes to forever dismantle the barriers of voting in the United States.

10. National Underground Railroad Freedom Center - Cincinnati, Ohio

On the banks of the Ohio River, a statue depicts a mother and her child escaping slavery. Living-Learning Programs. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Near the Ohio River, where thousands of slaves traveled in search of freedom, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center reveals the ongoing struggle for autonomy. From the historical vantage point of the Underground Railroad, the museum promotes the modern abolition of slavery. Due to widespread human trafficking, nearly 40 million people are currently enslaved around the world. As stated on the museum’s website, “Despite the triumphant prose of our American history books, slavery didn’t fully end 150 years ago. Today and throughout time, people around the world have struggled for their freedom. Yet, as forms of slavery evolve, so do the imaginations of those fighting for freedom.” Through artifacts, photographs and first-person accounts, the museum introduces the men and women who have resisted slavery. “Invisible: Slavery Today” is the world's first permanent exhibition on the subjects of modern-day slavery and human trafficking, challenging and inspiring visitors to promote freedom today.

Shannon Moran

is a Journalism major at the University of Georgia, minoring in English and Spanish. As a fluent Spanish speaker, she is passionate about languages, cultural immersion, and human rights activism. She has visited seven countries and thirty states and hopes to continue traveling the world in pursuit of compelling stories.

Zacatecas: a Vibrant Community in the Heart of Mexico

Travel deep enough into the Chihuahuan Desert and you’ll find yourself in Zacatecas. The Mexican state, known for its mining industry and colonial architecture, is often overlooked by travelers in favor of more popular cities such as Guadalajara, Mexico City and Acapulco.

Read More10 Animal Festivals From Around the World That You’ve Likely Never Heard Of

The festival of lights honors and worships Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, prosperity and beauty, and celebrates the relationship between humans and animals.

Read MoreThe Truffle Kingpin And Young Entrepreneur Based In New York City

At first glance, 24-year-old Ian Purkayastha seems like any other entrepreneur: he's motivated, crafty, disciplined, and personable. But behind the facade of a clever businessman lies a youthful energy and a passion for selling some of the rarest food on the planet: truffles. Purkayastha sells all kinds of truffles to 90 percent of New York's fine dining restaurants and has been peddling the fungi out of his backpack to the likes of Eleven Madison Park, Le Bernadin, and other Michelin-starred restaurants for nine years now.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON GREAT BIG STORY

Living Beyond the Gender Binary for Centuries

In Tehuantepec, a town in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, Lukas Avendaño and fellow muxes live beyond the gender binary. A muxe is an individual assigned male at birth who behaves outside roles traditionally associated with masculinity. Sometimes referred to as a third gender, muxe identity pre-dates Spanish imperialism in the Zapotec region. For Lukas, dressing in feminine Zapotec clothing is a political act, giving everybody the power and the liberty to decide who they want to be.

Read MoreThe Spirit of Morocco: Music, Architecture, and Living Heritage

There is more to Morocco than the gorgeous sand dunes of Merzouga in the Sahara or the majestic Atlas Mountains of the Maghreb region. Morocco’s music can take you on a journey through Spain, with flavors of Berber, hints of Arabic, and the Saharan style. Its architecture is a show stopping feature of pisé buildings, the finesse of Moorish exiles, and a glimpse into the Islamic influence of the Idrisid dynasty. The people bring craftsmanship and skill to their communities, combining history and culture in a way only Morocco can do.

Read MoreMexico

The videographer is Face du Monde and these are his comments on the video:

Read MoreExamining chicken intestines, reading the tea leaves, watching the markets – people turn to experts for insight into the mysteries that surround them. Manvir Singh, CC BY-ND

Modern Shamans: Financial Managers, Political Pundits and Others Who Help Tame Life’s Uncertainty

Aka Manai explains that there are two kinds of people in the world: simata and sikerei.

I am a simata. He is a sikerei. Sikerei have undergone transformative experiences and emerged with new abilities: They alone can see spirits.

I’ve experienced a lot since that night in Indonesia when Aka Manai told me this. I was there when an initiate first saw spirits, when he and the other sikerei wept as they saw their dead fathers swirling around them. I’ve attended seven healing ceremonies, witnessing the slaughter of dozens of pigs to accompany nights of dancing. But that chat with kind-faced Aka Manai, more than any other experience, grounded my understanding of sikerei in particular and shamanism more generally.

A sikerei treats an initiate’s eyes so he, too, can see spirits. Manvir Singh, CC BY-ND

I’m a cognitive anthropologist who studies why societies everywhere develop complex yet strikingly similar traditions, ranging from dance songs to justice to shamanism. And though trancing witch doctors may sound exotic to a Western reader, I argue that the same social and psychological pressures that give rise to healers like Aka Manai produce shaman-analogues in the contemporary, industrialized West.

What is a shaman?

Shamans, including the sikerei I’ve known in Indonesia, are service providers. They specialize in healing and divination, and their services can range from ending a drought to growing a business. Like all magical specialists, they rely on spells and occult gizmos, but what makes shamans special is that they use trance.

Trance is any foreign psychological state in which a practitioner is said to engage with the supernatural. Some trances involve complete immobilization; others appear as tongue-lolling convulsions. In some South American groups, shamans enter trance by snorting a hallucinogenic powder, transforming themselves into crawling, unintelligible spirit-beings.

Being a shaman often carries benefits, both because they get paid and because their special position grants them prestige and influence.

But these advantages are offset by the ordeals involved. In many societies, a wannabe initiate lacks credibility until he (and it’s usually a he) undergoes a near-death experience or a long bout of asceticism.

One aboriginal Australian shaman told ethnographers that, as a novice, he was killed by an older shaman who then replaced his organs with a new, magical set. When he woke up from the surgery and asked the old shaman if he was lost, the old man replied, “No, you are not lost; I killed you a long time ago.”

A long time ago, a short time ago, here, there – wherever you look, there are shamans. Manifesting as mediums, channelers, witch doctors and the prophets of religious movements, shamans have appeared in most human societies, including nearly all documented hunter-gatherers. They characterized the religious lives of ancestral humans and are often said to be the “first profession.”

Why are there shamans?

Why is it that when we lanky primates get together for long enough, our societies reliably give rise to trance-dancing healers?

According to anthropologist Michael Winkelman, the answer is wisdom. Drugs and drumming, he’s argued, link up brain regions that don’t normally communicate. This connection yields new insights, allowing shamans to do things like heal sickness and locate animals. By specializing in trance, shamans uncover solutions inaccessible to normal brains.

Based on my fieldwork, I’ve argued against Winkelman’s account. Rather than all integrating people’s psychologies, trance states are wildly diverse. Chanting, sipping psychoactive brews such as ayahuasca, dancing to the point of exhaustion, even smoking extreme quantities of tobacco – these methods produce profoundly different states. Some are arousing, others calming; some expand awareness, others induce repetitive thinking. In fact, the only element shared among these states is their exoticness – that once altered, the shaman’s experience stands apart from those of his onlookers.

As part of his anthropological fieldwork, author Manvir Singh speaks with an Indonesian shaman. Luke Glowacki, CC BY-ND

Not only are shamans’ experiences exotic, their very beings are, too. As Aka Manai emphasized to me, people understand shamans to be different kinds of entities, made “other” by their ordeals. The Mentawai word for a non-shaman, simata, also describes uncooked food or unripe fruit; it implies immaturity. The word for shaman, in contrast, means a person who has undergone a process: one who has been kerei’d and come out the other side a sikerei.

This otherness is crucial. Convinced that shamans diverge from normal people, communities accept that they have superhuman abilities. Like Superman’s alien origins and the X-Men’s genetic mutations, shamans’ transformations assure people that they deviate from normal humanness, making their claims of supernatural engagement more believable.

And once people trust that a specialist engages with gods and spirits, they go to them when they need to influence uncertainty. A sick child’s parent or a farmer desperate for rain prefers to nudge the forces responsible for their hardship – and a shaman provides a compelling conduit for doing so.

This, I suggest, is why shamans recur around the world and across time. As specialists compete in markets for magic, they fuel the evolution of practices that hack people’s intuitions about magic and special abilities, convincing the rest of us that they can control uncertainty. Shamans are the culmination of this evolution. They use trance and initiations to transcend humanness, assuring their clients that they can commune with the invisible beings who oversee uncertain events.

Who are the shamans of the industrialized West?

Most people assume that shamanism has disappeared in the industrialized West – that it’s an ancient tradition of long-lost tribes, at most resurrected and corrupted by New Age xenophiles and overeager mystics.

To some extent, these people are right. Far fewer Westerners visit trance-practitioners to heal illness or call rain than people have elsewhere in the world or throughout history. But they’re also wrong. Like people everywhere, contemporary Westerners look to experts to achieve the impossible – to heal incurable illnesses, to forecast unknowable futures – and the experts, in turn, compete among themselves, performing to convince people of their special abilities.

So who are these modern shamans?

A specialist you can turn to for help divining the mysterious forces at work in financial markets. Matej Kastelic/Shutterstock.com

According to the cognitive scientist Samuel Johnson, financial money managers are likely candidates. Money managers fail to outperform the market – in fact, they even fail to systematically outperform each other – yet customers continue to pay them to divine future stock prices.

This faith might come from a belief of their fundamental otherness. Johnson points out that money managers emphasize their differences from clients, exhibiting extreme charisma and enduring superhuman work schedules. Managers also adorn themselves with advanced mathematical degrees and use complicated statistical models to predict the market. Although money managers don’t enter trance, their degrees and models assure clients that the specialists can peer into otherwise opaque forces.

Of course, money managers aren’t the only experts to specialize in the impossible. Psychics, sports analysts, political pundits, economic forecasters, esoteric healers and even an octopus similarly sate people’s desires to tame the uncertain. Like shamans and money managers, they decorate themselves with badges of credibility – an association with the White House, for example, or a familiarity with ancient Tibetan medicine – that persuade customers of their special abilities.

As long as hidden forces shape our fates, people will try to control them. And as long as it’s profitable, pseudo-experts will compete for desperate clients, dressing in the most credible and compelling costumes. Shamanism is not some arcane tradition restricted to an ancient past or New Age circles. It’s a near-inevitable consequence of our human intuitions about special abilities and our desire to control the uncertain, and elements of it appear everywhere.

MANVIR SINGH is a PhD Candidate in Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

In Japan, Repairing Buildings Without a Single Nail

In the past, making and developing metal was too costly for carpenters in Japan. So instead of using nails, carpenters called “miyadaiku” developed unique methods for interlocking pieces of wood together, similar to a giant 3D puzzle. Takahiro Matsumoto has been a miyadaiku carpenter for over 40 years. He runs his company in Kamakura, Japan, where he assesses and repairs damage sustained by the many ancient temples in his city. Using ancient techniques, he ensures that these spiritual structures stay standing for generations to come.

Cultivating Japan’s Rare White Strawberry

In Japan, there's a specialty fruit craze sweeping the nation, from square watermelons to grapes the size of Ping-Pong balls. Still, the crown jewel of the luxury fruit basket is the white strawberry, bred to be a whole lot bigger and a whole lot sweeter than its classic red counterpart. We took a tour of Yasuhito Teshima's farm in Karatsu, Japan, to find out why so many people are spending a pretty penny for a taste of these famous white berries.

An 1811 wood engraving depicts the coronation of King Henry. Fine Art America

Inside the Kingdom of Hayti, ‘the Wakanda of the Western Hemisphere’

Marvel’s blockbuster “Black Panther,” which recently became the first superhero drama to be nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award, takes place in the secret African Kingdom of Wakanda. The Black Panther, also known as T’Challa, rules over this imaginary empire – a refuge from the colonialists and capitalists who have historically impoverished the real continent of Africa.

Read MoreIn Tokyo, These Trains Jingle All the Way

While most train stations alert passengers with basic dings and dongs, metro riders in Japan are treated to uniquely crafted melodies. Minoru Mukaiya is the mastermind behind these jingles—he’s made around 200 distinct chimes for over 110 stations. For Minoru, there’s no greater joy than bringing a little bit of music to millions across Japan every day.