Amongst the steep Tuscan hillside is an eccentric garden, home to a variety of unusual sculptures inspired by a deck of tarot cards. The Tarot Garden is the brainchild of artist Niki De Saint Phalle, who created the 22 works of art as a safe space for healing. After being committed to an asylum in the 1950s, she found refuge in art and wanted to build an environment that made others feel the same way. Today, visitors can explore the garden, built to be a “dialogue between sculpture and nature.”

Did 4 Million in India Actually Become Stateless Overnight

A released list of citizens has many worried about the future citizenship status of those excluded.

On July 30th a three year effort in India to update Assam, India’s National Register of Citizens (NRC), overseen by the Indian Supreme Court, released its final draft list. It is the first update since 1951 when the NRC was first carried out to count citizens and their holdings. Critics view the list as a reflection of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party’s policies as many of the four million excluded are Muslims, who make up ⅓ of Assam’s 32 million.

And because of the increased discrimination against Muslims in Assam, the intentions of the NRC update are under question. Many see the proposed 2016 Citizenship Amendment Bill as an embodiment of the discrimination. The amendment, were it to be passed, would grant citizenship to Hindus who fled Pakistan, Afghanistan, or Bangladesh—but not Muslims. Considering this, UN human rights experts have voiced the opinion that “local authorities… are deemed to be particularly hostile.”

The main concern though for international organizations is that even with legitimate documents, many officials are faulting individuals for minor technical issues. These errors include spelling errors, age inconsistencies, or confusion caused by various names. Aakar Patel, Executive Director of Amnesty International India, addressed such potentially misguided intentions by cautioning the government that the “NRC should not become a political tool.”

But how does one prove their citizenship? Each individual and every member of their family must provide two forms of documentation. The first is considered List A: documentation of an individual’s ancestors who were either on the 1951 NRC or any voter lists between 1951 and March 24, 1971. The cut-off date is in accordance with the 1985 Assam Accords, which stated any individuals who fled violence after Bangladesh declared independence a foreigner.

Then the individual most prove their connection to their legacy person through List B documents, such as a birth certificate. Still, both set of documents are difficult to obtain as many are poor illiterate families who either cannot access historical records or simply do not have the relevant documents.

Villagers wait outside their local NRC Center to verify their documents (Source: Reuters).

And for those not on the final list, they will be left with only those rights “guaranteed by the UN” according to Chief Minister of Assam, Sarbananda Sonowal. In other words, these individuals would be stateless: losing land rights, voting rights, and even access to welfare. For those individuals, the state has mentioned foreigners returning to Bangladesh; but Bangladesh has said it is not aware of any of its citizens living in Assam. And even though many news platforms have noted the construction of a new detention center to better process foreigners, Sonowal has said no one will be sent to detention centers

Considering this, South Asian director of the Human Rights Watch, Meenakshi Ganguly said the government must “ensure the rights of Muslims and other vulnerable communities.” And for many human rights activists, such protections are crucial to preventing a parallel to the Rohingya’s loss of citizenship in 1982.

Currently, officials are reaching out to individuals not on the list and educating them on how they can file claims and objections to their status. Members of the Supreme Court have also emphasized that the list “can’t be the basis for any action by any authority” in its current draft form. Although the “legal system will [ultimately] take its own course” according to Siddhartha Bhattacharya, Minister of Law and Justice.

TERESA NOWALK is a student at the University of Virginia studying anthropology and history. In her free time she loves traveling, volunteering in the Charlottesville community, and listening to other people’s stories. She does not know where her studies will take her, but is certain writing will be a part of whatever the future has in store.

"The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page." -Saint Augustine

"Do you want to know who you are? Don't ask! Act! Action will delinate and define you." -Thomas Jefferson

Reviving a Lost Community, One Loaf at a Time

The rich Jewish culture of a Ukrainian town was all but wiped out by the Nazis and the ensuing Soviet era. But one New York Jew is trying to bring it back, one loaf of challah at a time.

Escape from Egypt

This short film encompasses 21 days in Egypt. Ancient Egypt was a civilization in North Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River. Now present day Egypt covers the same area. The locations shown in this video are Cairo, Giza, Luxor, Aswan, Alexandria, and Ossis Siwa.

The Bronx River will never be the way it used to be, but it sure looks a lot better today than it did 20 years ago. RickShaw/flickr, CC BY-SA

From New York to Romania, Restoration Ecology is Helping Nature Heal (and maybe humanity, too)

New York City’s Bronx River used to be an open sewer, more useful for carrying industrial waste than for hosting fish. Today, thanks to the efforts of environmental groups and the communities that live along this 37-kilometre stretch of water, the river is steadily making its way back to health.

This is called restoration ecology. And from the northern reaches of New York City, as elsewhere, this 80-year-old philosophy is slowly making its way into the political mainstream, now taking climate change and modern living into account.

What restoration means

Success stories aside, there is a long-standing debate about the value of restoring natural environments.

Opponents say that we are not really able to return degraded landscapes to their previous states. And that claiming to have done so risks more destruction because it generates the expectation that things can always be put back together. This problem is known as moral hazard.

If restoration is feasible, then what’s to stop mining companies from blowing mountains up and then just “repairing” them?

On the opposite side of the debate are pragmatists, who believe restoration efforts to more good than harm. They’re not unconcerned about moral hazard, nor do they assert that humans are able to recover landscapes to exactly as they once were.

But, they say, if we can make terrible situations better for people and nature alike, why not try?

Aldo Leopold is a towering figure in this camp. His 1949 Sand County Almanac, an account of the now famous “land ethic” that urges people to reconnect with nature, is one of the cornerstones of the environmental movement.

Leopold’s trips to the Rio Gavilan region of the northern Sierra Madre in 1936 and 1937 helped to shape his thinking about land health. US Forest Service, CC BY

In the 1930s, he led the world’s first restoration project, the University of Wisconsin Arboretum, which established the basis of modern restoration ecology: returning degraded environments to their pre-disturbance states.

The Wisconsin project aims to recreate the pre-colonial environment once present south of lakes Mendota and Wingra, restoring prairie, savanna, forest and wetlands.

Though the aim of turning back the clock remains, environmentalists think about restoration in other ways, too. Given the rapid advance of climate change, it might not be possible to make landscapes as good as new (how would one tackle, say, the melting Arctic ice fields?), a goal that was, in any case, always complicated by the inherent dynamism of nature.

In this framing, partly theorised by William Jordan in his 2003 book Sunflower Forest, the historic condition of a natural environment is more a guideline than goal. Instead of restoring landscapes to a prior state, then, efforts should focus on changing our exploitative, destructive relationship with nature.

Increasingly, what restoration aims to heal today is the human–nature divide.

Our landscapes, ourselves

This is the view taken by the Bronx River Alliance, a not-for-profit organisation that has been engaged in restoring the Bronx River for the better part of a decade.

After centuries of being used as a dumping ground for industrial and residential waste, the river can never be returned to its pre-colonial state, replete with thick forest along its banks. Nor can we simply wish away the Kensico dam or the Cross-Bronx Expressway.

But it is possible to make the Bronx River healthy. The Alliance has learned that the key to doing this effectively is local involvement: to heal the river and keep it that way, it must become meaningful in people’s lives.

And the surest way for people to feel that they have a stake in something is by acting on its behalf. From West Farms and Hunts Point to Norwood and Williamsbridge, a network of Bronx volunteers engages in outreach and education, monitors the river’s vitals and helps restock it with fish.

Some 7,000 kilometres away, in the Southern Carpathian mountains in the Western Romanian commune of Armeniș, the World Wildlife Fund Romania and Rewilding Europe have been engaged in an effort to bring the European bison back to its historic range.

Home on the range. Wikimedia

The biggest land mammal of Europe was barely saved from oblivion after the second world war. And today’s population descends from the gene pool of just 12 individuals.

The return of this magnificent animal would help manage the mosaic environment of these mountains. Without big grazers like the bison, the open pastures that many animals depend on risk being taken over by trees.

Rather than simply sticking dozens of captive-bred animals in the Carpathian woods, the program has involved the local community at every step. It was Armenis villagers who built the fence that surrounds the reintroduction area, and Armenis villagers who protect the bison as park rangers.

The first reintroduction took place in 2014 when 17 animals were released into the forest. It was blessed by the local Orthodox Christian priest, and the community gathered by the hundreds to witness it. The association trying to turn the animals into an economic opportunity is also made up of locals.

Man vs nature

These are refreshing stories. Normally, the history of human engagement with the natural environment is a laundry list of failures and destruction: another species gone extinct, another precious swathe of land destroyed.

Ecological restoration projects like those underway in the Bronx and Armenis have the potential to reverse this trend, restoring not just nature but also humanity’s relationship with it.

By directly engaging in the act of restoration, people can come to understand themselves as animals who also live on and benefit from the land. Beyond the eco-centric arguments for nature’s intrinsic value, there is evidence that nature is good for our psychic health, relaxing us and improving the quality of our thinking.

If communities around the world follow in New York and Romania’s footsteps – supported by public funds thus making government a stakeholder in restoration projects – the wonder of nature may just outlast this century. That would be good for Earth, and for humanity.

MIHNEA TANASESCU is a Research Fellow, Environmental Political Theory at Vrije Universiteit Brussel

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

How the Dutch are Creating “Room for the River”

The 2.3 billion dollar project fighting rising sea levels in the Netherlands.

View of Rotterdam at sunset. Image credit: ZOOM.NL

One third of the Netherlands lies below sea level. Thus, the presence - and threat - of water has been a central part of Dutch culture since the first medieval farmers built dams and levees to control it. Now, a thousand years later, water technology in the Netherlands has evolved to pursue a goal that seems counterintuitive. To control water, and keep their citizens safe from it, the Dutch are in the midst of a 2.3 billion dollar project to let the water in.

The project is aptly called Room for the River—a national aim focussed on widening rivers, creating lakes, plazas, garages—all of which can function as public space but also provide somewhere for the water to go when lakes and rivers spill over. Part of the national shift in thought was due to massive amounts of flooding in the 1990s which forced many people to leave their homes. According to Harold van Waveren, a senior government advisor, the floods “were a wake-up call to give back to the rivers some of the room we had taken.”

In recent years, as cities such as New York and Miami struggle to find ways to protect their billion dollar real estate from rising sea levels, Dutch water engineering has become something of a national export —the Dutch equivalent of Swiss chocolate, or German cars.

“You can say we are marketing our expertise,” Dutch water expert Henk Ovink told the New York Times, “but thousands of people die every year because of rising water, and the world is failing collectively to deal with the crisis, losing money and lives.” He is happy to share his country’s pragmatic solution that views rising sea levels as an opportunity for environmental and social growth: a solution that features neither denial nor barrier building.

Dak Park, the largest rooftop garden in the Netherlands absorbs rain and CO2. Image Credit: dakparkrotterdam.nl

The Room for the River project is most visible in Rotterdam, the gritty city of the 70’s and 80’s that has reinvented itself as a hotbed of modern architecture, design, and business. Rotterdam is now home to innovative structures such as underground parking garages, plazas, and basketball courts that can double as retention ponds during a flood. A few miles outside the city in an area 20 feet below sea level, the project funded a new rowing course which can also hold water in emergencies. The course is part of the Eendragtspolder—an area of reclaimed rivers that doubles as a popular spot for biking, swimming, and community events. The area is also a river basin for the Rotte river and is expected to protect communities when the Rhine overflows—an anticipated 1 in 10 years event. The Eendragtspolder project represents the heart of the Room for the River project: pairing environmental reform with social reform. It’s what Mr. Molenaar, Rotterdam climate chief calls “investing in resilience.”

State of the art rowing course in the Eendragtspolder area doubles as water storage during extreme flooding. Image Credit: Willem Alexander Baan

It seems the United States, with its plans to build an colossal wall around lower Manhattan, has a lot to learn from the Dutch perspective. Unlike the Dutch water parks that serve as protection as well as social spaces, the fortress-like walls being erected along Florida’s coast and the plans for a wall around lower Manhattan will do little to protect from a storm and less for the quality of life of those surrounding it. Unlike water parks, walls separate rather than unite; in a storm they decide who is protected—who gets to live, and who doesn’t. In the best case, they only buy a city a couple of years before the sea rises higher and the barriers built become inconsequential.

“We can’t just keep building higher levees, because we will end up living behind 10-meter walls,” says Harold van Waveren, senior government advisor. “We need to give the rivers more places to flow. Protection against climate change is only as strong as the weakest link in the chain, and the chain in our case includes not just the big gates and dams at the sea but a whole philosophy of spatial planning, crisis management, children’s education, online apps and public spaces.”

EMMA BRUCE is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. She has worked as a volunteer in Guatemala City and is passionate about travel and social justice. She plans to continue traveling wherever life may take her.

Crowds Overwhelm the Queen of the Adriatic

Image Credit: The Local Italy

Venice is often called La Serenissima, Italian for “the most serene.” In previous years the island city was a haven for writers and artists who came from every corner of the world to wander its canal lined streets or write in the shade of a nearby cafe.

And yet, since the early 2000’s Venice has become anything but a peaceful retreat. Now it is almost impossible to roam those same streets of Proust and Pound without being entangled in the slow moving blockage of thousands of selfie stick bearing tourists. In fact, a total of 60,000 people visit Venice everyday, outnumbering the local population of 55,000.

Last year, Venice barely escaped being added to UNESCO’s “at risk” list for world heritage sites, where it would have joined cities such as Aleppo, Damascus and Vienna. (The city has one more year before it will be reassessed for addition to the list.)

Summer in Venice is “like war,” Paola Mar, the island’s head of tourism said in an interview with the Independent. According to Mar, the biggest problem is Venice’s proximity to many nearby summer resorts. “We’re two hours from Trieste, we’re one hour from Lake Garda, 90 minutes from Cortina, two hours from Rimini,” she said. “This is the problem.”

Residents pose with sign reading: Venice is not a hotel. Image Credit: The Telegraph

These resort tourists pose a greater risk to the city than the average—largely because they spend little to no money on the island, while taking up a great deal of space. They often arrive in bathing suits with packed lunches, intent on picnicing on already cramped bridges or in historic areas such as the Plaza San Marco. Mar calls these visitors “mordi-fuggi” or eat-and-run tourists. She says they perceive Venice as a kind of beach and fail to respect the historic city or its residents.

Even when these tourists spend money in the city it is usually at one of the kitchy vendors lining the streets in areas such as Rialto and San Marco. These tourist traps erode the business of the real artisans of Venice whose time-consuming crafts have no way to compete with the influx of uber cheap, made in China merchandise. “You’re asking me what it’s like to live with this crap?” Luciano Bortot, Venice native told the Guardian. “It used to be wonderful, we had lots of artisans … the problem now is the mass tourism, the people who come for just a few hours and see nothing – it’s as much of a nightmare for them.”

This influx of tourists has made it almost impossible for local residents to go about their usual lives. A year ago, 2,000 locals marched in a demonstration against the tourist industry in Venice. “Around 2,000 people leave each year,” Carlo Beltrame, one of the event’s organizers told the Guardian. “If we go on this way, in a few years’ time Venice will only be populated by tourists. This would be a social, anthropological and historical disaster.”

Despite the gravity of the tourist problem, the city has struggled to come up with a solution. Many have suggested a tax to enter the island, but this would violate the EU freedom of movement clause and the Italian constitution. The city also can’t raise the overnight tax that visitors pay when staying in hotels or b&bs because the rates are set nationally. “Our hands are tied,” Paola Mar told the Independent.

Another suggestion has been to close off Piazza San Marco to the public and charge for tickets—an action that is legal because of its designation as a closed monument site. Mar, however is reluctant to take this measure. To her, Venice “is a place where you’ve always met people. It was the first place in Europe to be a melting pot.” As Mar and many others see it, Venice is about inclusion, openness, ideas. Closing off the central monument feels dissident with the spirit of the city.

Image Credit: Comune di Venezia

For now, Venice has begun a campaign called #enjoyrespectVenezia that warns tourists with signs against inappropriate behavior such as littering, picnicking, swimming in canals, wearing bathing suits, and bicycling. Officials hope that that the hefty fines for each of these actions will incentivize tourists to behave better. The campaign also encourages visitors to venture off the beaten trail and pursue activities and landmarks that interest them. It also encourages tourists to stay away from cheap, made-in-china merchandise in favor of local artisans.

EMMA BRUCE is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. She has worked as a volunteer in Guatemala City and is passionate about travel and social justice. She plans to continue traveling wherever life may take her.

Photo of Kelley Louise speaking at 2017 Impact Travel Global Summit. Photo by Naomi Figueroa.

Meet Kelley Louise, Founder and Executive Director of Impact Travel Alliance (ITA)

Impact Travel Alliance (ITA) is an organization that seeks to raise awareness about sustainable travel. The nonprofit defines themselves as a “community of doers and dreamers united by a love of exploration and doing good.” This community has grown over the years, since its birth under the name Travel + SocialGood, to its current embodiment of 15,000 advocates and 20 chapters in cities worldwide. Together, this community that was once imprisoned into a niche is breaking into the mainstream and spreading the word that tourism can be used to make a difference. Kelley Louise, the Founder and Executive Director of ITA, recently offered CATALYST some answers to questions about the role of her team’s work in raising awareness about sustainable travel.

When did you start ITA and what inspired you to begin this movement?

I always knew that I wanted to work within the travel industry and make a positive impact but when I started I didn’t exactly know how that would take shape. When I started learning about sustainable tourism, I felt like there was this huge part of the industry that had a lot of potential. But there wasn’t really a community that I felt like I would want to be a part of within the industry. What’s cool about ITA is we are a global community of changemakers around the world and there’s strength in our numbers. That is very valuable in terms of being able to collectively work together to push the industry forward. Community has always been at the forefront of what we’re building and creating. We have global conferences. We have local chapters. We have a media network. We’ve developed those initiatives based off of the need from the industry as well as feedback from the community at the same time. It has come to life in a very organic way for that reason.

The original name of ITA was Travel + SocialGood. Is there a specific reason for this and if so, what was the intent behind it?

Yes, and we have a full blog post on this subject. However, to give a general overview: I wanted something that really reflected who we had grown to be as an organization. Again, having something that was really focused on community at the forefront. “Alliance” was something that made you feel like you are part of something bigger than yourself. The big push was having a name that felt more inclusive as well as reflective of the organization we had grown into…

For those who want to learn to travel with a more sustainable mindset but don’t fully understand the concept, how exactly do you define sustainable tourism?

To distill it into its easiest definition I would say that it is tourism that has a positive impact on the environment, the economy and the culture of the destination you are visiting. It has that triple bottom line approach to it. We [ITA] try to make it easier to understand in order to get more people excited about being involved in this movement.

The 2018 Thought Leadership Study, released by ITA as a research endeavour about the growth/need of sustainable tourism, mentions that the goal of ITA is to reach out to the “average traveler”... How inclusive is this definition of your average traveler?”

The average traveler is your mother in law or your uncle or your brother or someone who isn’t already necessarily trying to do good. We are looking at the entire industry. I think the big push behind everything we do is to build a more impactful industry. Sustainable tourism is not a new concept. It’s been around for a long time but when you look at the average consumer base of people who are traveling, they are not traveling sustainably. Most travelers, even if they want to travel and make a positive impact do not know how. They might also not know that their travels can be sustainable. You can apply sustainable tourism to any type of travel whether that’s a cruise in the caribbean or a business trip to Chicago.

The Thought Leadership Study also says that big entities and corporations (i.e. Expedia) aren’t necessarily readily offering the opportunity to travel sustainably.. If this is so, how does an average traveler come across experiences that are “sustainable”?

The biggest thing travelers can do is to understand that sustainability is a journey. Everyone is constantly evolving and constantly doing better. Sustainability in itself can always be improved. It comes down to a lot of little changes that make it easier over time. As an organization, we’re focused on progress over perfection. Additionally, it’s important travelers understand sustainability is a lifestyle. If you look at your own lifestyle and what you do on a day to day basis and then start making travel decisions, those sustainable habits will become second hand nature. For example, straws. It’s great that everyone is switching straws; either using an alternative or not at all.. What’s cool about this model for sustainability is that it opens the door to a wider conversation. [This transition away from straws] might make it easier to remember a reusable bag or to try to purchase something not wrapped in plastic. If you were to try to completely cut plastic out of your life, it would be very hard. It’s a lot easier to take the first step.

Another good point about making decisions when traveling abroad is in regards to how you are spending your money and what products you’re buying. If you’re buying a souvenir, think about where and how its made. Where is the money going? Is it ethically sourced? Were labour practices done well? Where are you going to sleep at night? All these little decisions should be considered through the lens of sustainability. Question: How am I having an impact on the world around me through these purchase decisions?

You mentioned that sustainability is a concept that has been around for awhile. Why is now the best time for growth and why is the marketspace ready?

There are a lot of reasons. In a way, it's almost a perfect storm of things coming together from different directions and different sides of the industry. A core part of what contributes is that consumers are seeking sustainable experiences. There is a want within the industry to create these products and platforms [with reference to statistics in the Thought Leadership Study]. There is research that backs up the fact that people want to have a positive impact on the destinations they are visiting. It’s a better experience at the end of the day; more immersive to the given destination.

There’s also a huge need. We have more and more travelers each year, creating issues like overtourism. In Barcelona, for example, people are protesting the tourists. In Thailand they shut down a beach too many tourists were visiting and destroying. Sustainable tourism offers a way to have a more innovative approach towards issues of the like. There’s a need and business case for it. Sustainable tourism is a great business decision. You can increase your profits. You can increase brand loyalty. There’s many reasons but these are the three core reasons. There’s a rise in demand. There is a need because of over tourism and there’s a business case for sustainability.

Does traveling sustainability anticipate that some destinations should be visited over another out of respect for issues like overtourism? How does this decision play into sustainable travel?

It’s all about being mindful about how you spend your money. In terms of choosing a destination, consider how you can make an impact on that community. That might mean that if they are protesting tourists in a certain city then perhaps you consider going in the off season or you consider staying outside city limits. It’s about being considerate of the locals. There is always going to be different [decisions to make] for different destinations. Doing research beforehand can be beneficial. You can also ask the locals how to be a respectful tourist. Do you stay in a homestay? In a hotel? How can you have that high positive impact on the destination you are visiting?

How can we get involved? Both with your organization and with this movement —in small and large part?

On our website, impacttravelalliance.org/get-involved, we have a list of ways to get involved. Whether you’re a business owner or a traveler, whatever side of the industry you’re on, there’s a ton of ways to get involved with our organization. There’s not a one-size fits all. In general, I would start with the little habits. They make a big impact over time. When we’re all working together towards the greater good then there’s a lot of contextual impact over time.

ELEANOR DAINKO is an undergraduate student at the University of Virginia studying Spanish and Latin American Interdisciplinary Studies. She recently finished a semester in Spain, expanding her knowledge of opportunity and culture as it exists around the world. With her passion to change the world and be a more socially conscious person, she is an aspiring entrepreneur with the hopes of attending business school over seas after college.

Japan’s Town With No Waste

The village of Kamikatsu in Japan has taken their commitment to sustainability to a new level. While the rest of the country has a recycling rate of around 20 percent, Kamikatsu surpasses its neighbors with a staggering 80 percent. After becoming aware of the dangers of carbon monoxide associated with burning garbage, the town instated the Zero Waste Declaration with the goal of being completely waste-free by 2020.

A camp for displaced Rohingyas in the city of Sittwe in western Myanmar. Cresa Pugh, CC BY

I visited the Rohingya camps in Myanmar and here is what I saw

Myanmar recently claimed to have repatriated its first Rohingya refugee family. But, as an official from the United Nations noted, the country is still not safe for the return of its estimated 700,000 Rohingya Muslim refugees, who fled to Bangladesh in 2017 to escape an ongoing state-sponsored military campaign and persecution from Buddhist neighbors.

Rohingya refugees holding placards, await the arrival of a U.N. Security Council team in Bangladesh, on April 29, 2018.AP Photo/A.M. Ahad

Indeed, in recent times, the Myanmar military has been building a fence along the 170-mile border and fortifying it with landmines, to prevent the Rohingya from returning to their villages.

I spent two months between June and July 2017 talking to Rohingya individuals who are still in the country living in an internally displaced person camp, about their experiences of violence, displacement and loss. My research shows the difficult conditions under which the Rohingya live in Myanmar today and why there is little hope of a safe return for the vast majority of the refugees anytime soon.

Conditions in Rohingya camps

Since 2012, more than 1 million Rohingya refugees have fled their homes in Rakhine. The vast majority that fled in 2017 sought refuge in Bangladesh, where fears of an imminent monsoon flood are currently looming. In addition, there are an estimated 3.5 million Rohingya dispersed across the globe, the majority of whom have either fled or were born into exile due to violence in their homeland.

Those who remain in Rakhine are either in their homes and are prohibited from traveling away from their villages, or dwell in temporary camps. There are roughly 120,000 Rohingya encamped in settlements, located on the outskirts of Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine, just a few miles from their former homes.

Most residents have lived in the camps since 2012, despite the fact that they were forcibly relocated by the government on a purportedly temporary basis. The camps are managed jointly by the government and military, and receive substantial assistance from international NGOs and U.N. agencies. However, there have been times when even the humanitarian organizations have been barred from delivering food rations and other goods and services by the government and military.

I received government approval to visit the camps last year. In Northern Rakhine, I was interrogated by military officials, and one officer came to my friend’s home where I was having dinner to ask for my passport and travel documentation. I was then allowed to stay.

When I visited the Rohingya camp on the outskirts of Sittwe, the fear was palpable. The only road leading to the camp was dotted with police checkpoints staffed by AK-47-wielding officers. One of my interviews was cut short because there was a rumor of a man being shot dead, while trying to escape the camp. The entire quarter was put on high alert.

I happened to be visiting the camp on Eid al-Fitr, the last day of Ramadan when Muslims break their monthlong fast. In the midst of the tension, there was joy as well. Young girls with freshly oiled hair adorned with satin bows and sequined dresses played alongside the officers with machine guns.

At the same time, there was also the trauma of not being able to freely honor and practice their faith. Residents of the camp spoke to me of the limitations on their religious expression. They explained how camp officials required them to remain in their homes from 10 p.m. onward and how it was not possible for them to gather at a mosque to participate in traditional celebrations central to the Islamic faith, even during Ramadan.

Destruction of mosques

Another sad reality for many Rohingya in Myanmar is the destruction of their religious buildings. All mosques in Rakhine have been either destroyed or shuttered after communal riots broke out between the local Buddhist population and Rohingya in 2012.

A mosque in Sittwe, Rakhine state, that was torched and damaged in the 2012 conflict. CC BY

Many of the abandoned mosques that I saw had been reduced to rubble, and many of them continued to be heavily policed. The government has also made it illegal to construct new mosques to replace those that have been destroyed or to make repairs or renovations. In addition, in 2016 state authorities announced plans to demolish dozens of other mosquesand madrasas (Muslim religious schools), based on a claim, that they had been illegally built.

In the camp, I learned that residents were allowed to build two small mud and thatch huts, which would serve as their mosques. These small structures were hardly able to accommodate the thousands who wanted to pray there. People must therefore pray separately, a move which has deeply fractured social relations within their community.

Residents reminisced about the beauty of their now demolished mosques, some refusing to even call the structure in the camp a mosque for they believed it was disrespectful to their religion. For some residents, offering prayers in this structure was not a true practice of their faith. As one young man told me, “Without being able to worship Allah, we no longer have our lives.”

Furthermore, it is only men who are allowed into this space. Women are required to pray within their shelters. During one of my interviews with a young man, I saw his wife crouching down on the dirt floor in the rear corner of their bamboo hut amid a pile of cookware. I asked what she was doing. “Praying,” he said.

Even before the 2012 military crackdown, restrictions had been placed on many of the religious obligations and rituals of the Rohingya. From my interviews I learned that for the better part of the decade, no Rohingya living in Rakhine have been able to engage in spiritual pilgrimage to Islamic holy sites in other areas of the country and globe. They have also been prohibited from inviting Muslim religious leaders to visit their mosques.

When I spoke with Rohingya individuals in the camp, they told me the deep religious significance of these practices. To many, it wasn’t just a denial of their religiosity, but of their humanity. “Our history is Rohingya, our religion is Islam, and our home is Rakhine,” said one older man, as he showed me the damp, often muddy, dirt floor where his family of eight sleep has slept every night since June 9, 2012.

Not losing faith

Over the past several years, opposition to the Rohingya has deepened. Many residents of Rakhine believe that the Rohingya are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, referring to the fact that some of the Rohingya trace their heritage to Bengal, an area that became part of British India in the mid-18th century and from which many people migrated during the colonial period.

A mosque in one of the Rohingya camps on the outskirts of Sittwe. Cresa Pugh, CC BY

Nonetheless, despite their persecution, the individuals with whom I spoke remained unwavering in their faith. As I was departing, a young man, who had spent five years, or roughly a third of his life, in the camp, told me, “This has only made me stronger. The government has tried to destroy our religion and destroy our people, but a child never loses faith in his mother, and we can not lose our faith now.”

CRESA PUGH is a doctoral Student in Sociology & Social Policy, Harvard University.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

"I see my path, but I don't know where it leads. Not knowing where I am going is what inspires me to travel it." -Rosalia Castro

"The great aim of education is not knowledge but action." -Herbert Spencer

The Festival of Glowing Giants

Asako Kitamura never set out to break any barriers. She simply grew up wanting to become a master nebuta maker, just like her father before her. She spent years perfecting the art of building nebuta, giant paper floats built to take on the shape of warrior gods. This year, Mitamura made history as the first woman to win first place at Japan’s 300-year-old Aomori Nebuta Festival.

Food Insecurity Affects More than 41 Million Americans

In a nation of plenty, why do 1 out of 8 Americans have uncertain or limited access to food?

In America 1 out of 10 don’t have enough to eat, much more than the 1 in 20 in Europe (Source: Bread Institute for America).

Going hungry in America is not what most would expect. Hunger might mean sacrificing nutritious food for inexpensive, unhealthy options. It might mean periodic disruption to normal eating patterns. And increasingly such hunger occurs among white families, in the suburbs, and among obese people. In other words, any community can be affected; and in 2017, the USDA reported 12.3% of American households are food insecure. Hunger today is a result of tradeoffs between food and other costs—such as health care, bills, and education.

However, hunger does not accurately depict food insecurity in America. Hunger is a prolonged, involuntary lack of food that can lead to personal or physical discomfort. Conversely, food insecure, coined in 2006 by the USDA, defines a household with limited or uncertain access to food. Food insecurity results from limited financial resources and makes it difficult to lead an active, healthy lifestyle. Further, food insecurity can be categorized either as low food insecurity (reduced quality of food, but not intake) or high food insecurity (both reduced quality and intake).

No matter the category given, food insecurity has serious effects. This is most evident in the need for 66% of Feeding America customer households to choose between medical care and food, according to a 2014 study. Considering many food insecure individuals have diabetes or high blood pressure, medical care can be critical. A study by the Bread for the World Institute in 2014 estimated hunger creates $160 billion in healthcare costs. This includes mental health problems, nutrition related issues, and hospitalizations among other potential costs.

Further, 13 million of food insecure individuals are children and 4.9 million are seniors: two critical groups whose bodies rely on proper nutrition. For example, the effects of hunger in children have been known to delay development, cause behavioral problems, and even increase the chances a child will repeat a grade.

One solution for food insecurity is federal food assistance programs. Indeed, 59% of food insecure households are part of at least one major federal food assistance program— but 25% of households do not qualify. The most well-known of these federal programs is SNAP, or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. SNAP requires your gross income be at or below the poverty line by 130%, allowing for adjustments with family size. Still, the average amount per person is around $133.07 a month—or less than $1.50 per meal.

The desired solution though is the end of food insecurity in America. A major force behind this future is the domestic nonprofit, and hunger relief organization, Feeding America. Feeding America supports food banks, funds research, provides meal programs, mobilizes anti-hunger advocacy, and educates the public among other initiatives.

Overall, Feeding America and its partners served 1 out of 7 Americans in 2017. It was able to do so as it works together with 200 food banks and 60,000 pantries. Each affiliated food bank, a non-profit that stores food for smaller organizations, is evaluated according to industry practices and food safety laws. Additionally, all staff receive food safety training. These practices ensure all food is safe when distributed at the food pantries, which directly serve their communities.

Much of the food was higher quality too: around 1.3 billion pounds of nutritional food was delivered to food banks in 2017. Some food is food waste, in 2017 3.3 billion pounds were rescued from landfills and redistributed for consumption from partner companies, such as Starbucks. And all these small initiatives are directly helping communities, making food security an increasing possibility for the future.

TERESA NOWALK is a student at the University of Virginia studying anthropology and history. In her free time she loves traveling, volunteering in the Charlottesville community, and listening to other people’s stories. She does not know where her studies will take her, but is certain writing will be a part of whatever the future has in store.

SOUTH AFRICA: Dancing For Freedom

Masabatha “Star” Tete has been dancing since childhood. When she discovered pantsula, an energetic dance form known for its fast-paced footwork, she knew there was nothing she’d rather do. Originating in South Africa’s townships, pantsula was created during apartheid as protest during a time when many forms of expression were restricted. Today, dancers like Star and the organization she works for, Impilo Mapantsula, are keeping the culture and history of pantsula alive through dance crews and competitions. And although traditionally considered a male form of dance, Star and other female dancers have been breaking down barriers for generations to come.

CHILE: Atacama

The Atacama Desert is a virtually rainless plateau in South America, covering a 600-mile (1,000 km) strip of land on the Pacific coast of South America, west of the Andes mountains. According to NASA, National Geographic and many other publications, it's the driest desert in the world.

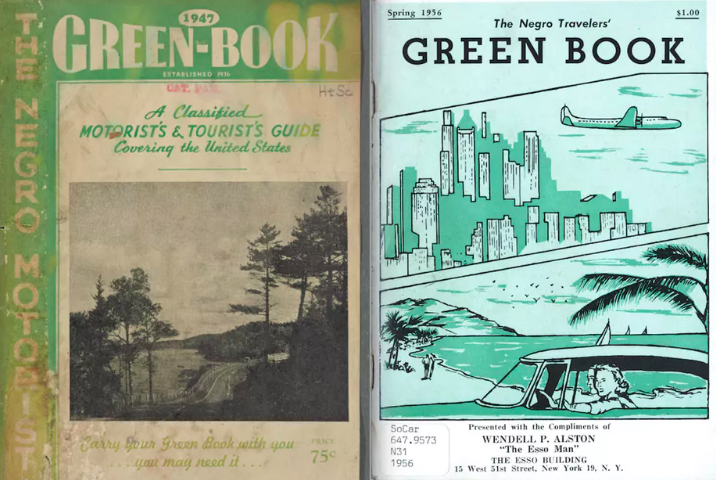

The 1947 and 1956 editions of the ‘Green Book,’ which was published to advise black motorists where they should – and shouldn’t – frequent during their travels. Image on the left: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. Image on right: Courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C

‘Traveling While Black’ Guidebooks May be Out of Print, but Still Resonate Today

In the summer of 2017, the NAACP issued a travel advisory for the state of Missouri.

Modeled after the international advisories issued by the U.S. State Department, the NAACP statement cautioned travelers of color about the “looming danger” of discrimination, harassment and violence at the hands of Missouri law enforcement, businesses and citizens.

The civil rights organization’s action had been partly prompted by the state legislature’s passage of what the NAACP called a “Jim Crow bill,” which increased the burden of proof on those bringing lawsuits alleging racial or other forms of discrimination.

But they were also startled by a 2017 report from the Missouri attorney general’s office showing that black drivers were stopped by police at a rate 85 percent higher than their white counterparts. The report also found that they were more likely to be searched and arrested.

When I first read about this news, I thought of the motoring guidebooks published for African-American travelers from the 1930s to the 1960s – a story I explore in my book “Republic of Drivers: A Cultural History of Automobility in America.”

Although they ceased publication some 50 years ago, the guidebooks are worth reflecting on in light of the fact that for drivers of color, the road remains anything but open.

The half-open road

In American popular culture, movies (1983’s “National Lampoon’s "Vacation”), literature (“On the Road”), music (the 1946 hit “Route 66”) and advertising have long celebrated the open road. It’s a symbol of freedom, a rite of passage, an economic conduit – all made possible by the car and the Interstate Highway System.

‘Get your kicks on Route 66,’ Bobby Troup crooned in his hit song.

Yet this freedom – like other freedoms – has never been equally distributed.

While white drivers spoke, wrote and sang about the sense of excitement and escape they felt on automobile journeys through unfamiliar territories, African-Americans were far more likely to dread such a journey.

Especially in the South, whites’ responses to black drivers could range from contemptuous to deadly. For example, one African-American writer recalled in 1983 how, decades earlier, a South Carolina policemen had fined and threatened to jail her cousin for no reason other than the fact that she had been driving an expensive car. In 1948, a mob in Lyons, Georgia, attacked an African-American motorist named Robert Mallard and murdered him in front of his wife and child. That same year, a North Carolina gas station owner shot Otis Newsom after he had asked for service on his car.

Such incidents weren’t confined to the South. Most of the thousands of “sundown towns” – municipalities that barred people of color after dark – were north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Of course, not all white people, police and business owners behaved cruelly toward travelers of color. But a black individual or family traveling the country by car would have had no way of knowing which towns and businesses were amenable to black patrons and visitors, and which posed a grave threat. The only certainties for African-Americans on the road were anxiety and vulnerability.

‘A book badly needed’

“Would a Negro like to pursue a little happiness at a theatre, a beach, pool, hotel, restaurant, on a train, plane, or ship, a golf course, summer or winter resort?” the NAACP magazine The Crisis asked in 1947. “Would he like to stop overnight in a tourist camp while he motors about his native land ‘Seeing America First’? Well, just let him try!”

Despite the dangers, try they did. And they had help in the form of guidebooks that told them how to evade and thwart Jim Crow.

“The Negro Motorist’s Green Book,” first published in 1936 by a New York letter carrier and travel agent named Victor Green, and “Travelguide: Vacation and Recreation Without Humiliation,” first published in 1947 by jazz bandleader Billy Butler, advised black travelers where they could eat, sleep, fill the gas tank, fix a flat tire and secure a myriad of other roadside services without fear of discrimination. The guidebooks, which covered every state in the union, drew upon knowledge hard-won by pioneering black salesmen, athletes, clergy and entertainers, for whom long-distance travel by car was a professional necessity.

Pages from an original 1947 edition of the ‘Green Book’ highlight businesses in Mississippi and Missouri. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. 'The Negro Motorist Green Book: 1947' The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1947

“It is,” a “Green Book” subscriber wrote to Victor Green in 1938, “a book badly needed among our Race since the advance of the motor age.”

Acknowledging the era’s racial tensions and dangers of travel, the 1956 edition reminded drivers to “behave in a way to show we’ve been nicely bred and [were] taught good manners.”

The 1950 edition of ‘Travelguide.’ Cotten Seiler, Author provided

It pointed to certain states that would be more amenable to black travelers: “Visitors to New Mexico will find little if any racial friction there. The majority of the scores of motels across the State accepts guests on the basis of ‘cash rather than color.’”

Yet even as they sought to ease the black traveler’s passage through an America in which racial discrimination was the norm, the guidebooks, whose covers often featured well-heeled travelers of color with upscale automobiles and accessories, also asserted African-Americans’ claims to full citizenship.

The guidebooks’ images and text conveyed an attitude of indignation and resistance to the racist conditions that made them necessary.

“Travel Is Fatal to Prejudice,” the cover of the 1949 edition of the “Green Book” announced, putting a spin on a famous Mark Twain quote.

In 1955, “Travelguide” declared, “The time is rapidly approaching when TRAVELGUIDE will cease to be a ‘specialized’ publication, but as long as racial prejudice exists, we will continue to cope with the news of a changing situation, working toward the day when all established directories will serve EVERYONE.”

Is racial terror really over?

Travelguide and the Green Book did indeed shut down in the 1960s, when the civil rights movement sparked a profound transformation in racial law and custom across the country.

Today, copies can be found in research archives at Howard University, the New York Public Library and the Library of Congress. The guidebooks have been the focus of a growing body of print and digital scholarship. The University of South Carolina, for example, has built an interactive map that allows visitors to search for all of the businesses listed in the 1956 edition of the “Green Book.”

In popular culture, a play, a children’s book and a forthcoming Hollywood film starring Mahershala Ali all center on these travel guides.

While the story of these books recall an era of prejudice many regard as bygone, there remains much work to be done.

The NAACP’s decision to issue a travel advisory calls attention to the dangers that continue to be associated with “driving while black.” The highly publicized recent deaths of Sandra Bland, Philando Castile and Tory Sanford are the starkest examples of what can happen to black drivers at the hands of police. Studies have shown that across the nation, police are still much more likely to stop and search drivers of color.

If guidebooks for drivers of color are unlikely to make a return, it is because the internet now fulfills their role, not because the “great day” of racial equality the “Green Book” heralded 70 years ago has arrived.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Chasing Away Evil Spirits in Bulgaria

Each year, people across Bulgaria gather in Blagoevgrad to partake in the annual Kukeri Festival. Draped in elaborate costumes made from long goat hair, participants dance away the evil through a procession involving the ringing of bells. Dancers wear carved wooden masks that depict the faces of beasts and jump in a centuries-old ritual intended to drive away evil spirits. Desislava Ilieva started attending festivals as a child and now continues to uphold her family’s tradition by wearing costumes handmade by her father.