This video was shot over a 5 day trip to Tokyo in January 2016. It was Christoph Gelep’s (videographer) first time visiting Japan, a place he had always wanted to see. With a population of 35 million, Tokyo is the largest metropolitan area in the world. Due to this, Christophe soon realized how lively and energetic this city really is.

Searching Japan's Ghost Island

Hashima (“battleship” in Japanese) Island is a 16-acre abandoned island about 10 miles off the coast of Nagasaki. With crumbling concrete buildings, abandoned undersea coal mines and a dramatic surrounding sea wall, the island is an eerie testament to Japan’s period of rapid industrialization. It is also a stark reminder of its dark history as a site of forced labor during World War II.

Threads of Hope and Beauty: Capturing the Resilience of Life and Culture

For more than two decades, through the lens of my camera, I have sought out the hope and beauty woven into the fabric of all life and all peoples, from forest to ocean. In the face of the myriad unrecognized plights and urgent truths of our shared human and planetary condition, these shimmering threads promise change.

Images / Words © Cristina Mittermeier / Words © Kim Frank

National Geographic photographer and co-founder of SeaLegacy, Cristina Mittermeier, releases her new book this month, Amaze, published by teNeues. An intimate collection of over 25 years, Amaze combines impassioned poetic storytelling, indigenous wisdom, and an urgent plea to protect our planet. Amaze takes you on a insightful and hope-filled journey where the human spirit lifts from every page. Here is a glimpse into the book’s luminous world.

Ta’kaiya Blaney, a singer, songwriter, and drummer for her people, the Tla’amin First Nation of British Columbia, is seen in a cedar cape. The youngest speaker at the United Nations Indigenous Forum, she is a fierce advocate of indigenous rights and environmental protection.

AS WITH MANY IMPASSIONED JOURNEYS, MY LIFE AS A CONSERVATIONIST AND ARTIST BEGAN WITH A LESSON.

A lesson that rattles in my soul like a grain of sand in a chambered nautilus shell. Urging me onwards; reminding me why I do this work. Curled deep within this hidden spiral is the unwavering memory of one of the most powerful photographs I never took.

The densely knit Amazon rainforest; home to countless indigenous peoples and the once-mighty Xingú River, now forever tamed.

When I was a young and inexperienced photographer, I was sent on an assignment to a remote corner of the Brazilian Amazon. Flying from town to town, over vast stretches of rainforest, and in increasingly small airplanes, I finally arrived at the Kayapó village of Kendjam; home to one hundred and fifty individuals. My mission was to give a face and a name to the thousands of indigenous people whose lives were soon to be impacted by the construction of the Belo Monte dam.

Young Kayapó children will sit or stand patiently for hours, as their mothers paint their bodies with genipap, a dye made from a forest fruit of the same name. Being painted, and painting others, is a very important form of social bonding in these remote Amazonian villages.

Late one afternoon, I saw a group of women coming up from the river; one of them carrying a tiny baby in her arms. It dawned on me that they had just given this newborn his first bath in the river; a vital ritual bath that ties a person’s fate to the fate of the river. And I had missed it. I consoled myself, naively thinking I that could find the mother in the morning and ask her to bring her baby back down to the water, hoping to recreate what I had missed. Tragically, we woke to the news that the infant had not lived through the night. By the time I had figured out what was happening, the women had already buried the tiny body, and I had missed that ritual as well.

Dismayed, I began to wonder if I was up to the challenge of this assignment, wishing the editors had sent a more experienced photographer, when out of the corner of my eye I saw a figure approaching. It was the mother of the baby, walking straight towards me and bawling. Nobody was going near her. As she came closer, I saw that she was cradling a dirty bundle.

In her sorrow, she had dug out the body of her dead child, and was carrying him around. Clutching a machete in her hand, she was hitting her forehead with the blunt edge as she screamed out her sorrow. Her face, her dress, her dead son; all were covered in mud and blood.

I stood there, gripping my camera with frozen fingers; paralyzed.

I could think only of my children back home and how I would feel if a stranger shoved a camera in my face just after I had lost my child. I am ashamed to admit that I did not take any photos.

The Xingú river is intimately woven into the fabric of Kayapó life. This young girl’s eyes speak of a beloved waterway about to be dammed forever, of pride in her people’s traditions, of fear for a future unknown, and of the innocence that every child deserves to live with.

A few months later we learned that the dam had been approved and construction was to begin immediately. I thought about the beautiful, generous people I had met and how their lives would be changed forever.

To this day, I am haunted by this question:

Would their fate have been been different if I had dared to do my job and take those difficult photographs? What if my images had been beautiful enough, or dramatic enough, to change the conversation?

The Kayapó people believe that if they are good to the forest and to the river, they will be provided with everything they need to sustain themselves.

I will never know, because that day I lacked the courage to press the shutter: a mistake I never made again. From that moment forwards, I pledged never to hesitate and to make images that matter.

For centuries the Kayapó way of life has been deeply entwined with the rivers that flow through the forest. For me, this image is a powerful symbol of nature’s familial hold on the human spirit, reminding us that nature is so much more than a commodity to exploit.

Over the course of my career I have witnessed photography’s ability to shape perceptions, help societies pause and reflect, and inspire change. Being a photographer allows me to share my deepened understanding of the truth that all things in nature are part of one vast ecosystem.

Unlike people, the Earth’s diverse waterways, wildlife, and forests are intricately woven into the fabric of the whole; not claiming a separate existence. My hope is that my images will inspire a stronger connection with the nature that lies within and around us, as it is infinitely worthy of our deepest respect and care.

In a raw world that seems to bleed everyday with shriveling resources, human tragedy, and environmental ruin. Where every moment with a press of a button or a swipe of a screen, we are assaulted with distressing news, stories and images that threaten our sense of security and dim our lights, we must find ways to remain optimistic.

We must work to remove the physical and metaphorical barriers that block our meaningful connection to one another and to our planet. In my twenty five years documenting remote tribal communities around the world I have learned important lessons from their collective wisdom.

A young girl of the Afar tribe, from Ethiopia. Her people are fiercely proud and independent, having lived forever in the harsh deserts of the Horn of Africa, as semi-nomadic cattle and camel herders.

Spending time with Indigenous peoples has taught me that abundance is not measured in the things that we own, but in the strength of our human spirit, and in the depth of our connection to the natural world.

From the Amazon to the Arctic, these communities nurture an intimate awareness of the web of relationships that have sustained them in harmony with nature, for millennia. I have long thought about how I could share my own interpretation of this intuitive wisdom. Among the Kayapó, the Gitga’at, the Inuit, and the many other Indigenous communities I have photographed, I have witnessed a myriad of common strands — spiritual and physical; past and future. Woven together, they become the exquisite and universal fabric of something that I have come to call “enoughness”.

Made from the feathers of birds of paradise, the Indigenous peoples in the highlands of Papua New Guinea pride themselves on elaborate personal decoration. This woman’s spectacular headdress had been passed down from generation to generation.

My personal true north for navigating the complexities and contradictions of modern life with more planetary integrity, I search for these threads of enoughness: belonging, purpose, sacred ecology, spirituality, and creative expression in the people I meet, and the experiences I have.

I describe and show enoughness within the words and images in the first part of my book, Amaze, and I share an excerpt with you here. It is my hope that enoughness can be recognized as a path to a more fully expressed life, as we seek to entwine these threads more deeply into our own personal tapestry.

I am often asked if I gave gum to these boys from the highlands of Papua New Guinea, but the answer is no. They were at the Mount Hagen Sing-Sing, a festival that celebrated the most culturally-intact tribe, and delighted in surprising me with their bubbles.

We all yearn to belong, whether it be to a people, or to a place.

On the spray-soaked shorelines of the Pacific Northwest, a part of the world that I am now fortunate enough to call home, the Sundance Chief of the Tsleil-Wuatuth First Nation shared with me what belonging means to him. For his people, the land is not something that you own, nor is it a commodity to be bought and sold. Instead, it is something that you belong to.

For over 30,000 years the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation and their ancestors have lived in the region we now call Burrard Inlet.

Rock, tree, river, or hill, crow, bear, or human, all were formed from the same elements by the Ancestors long ago. Their land is alive with relations, no matter the shape that relation may take. When you love, need, and care for the land, in return, the land will love, need, and care for its people. For the Tsleil-Waututh, the land is both family and self.

It is the ultimate expression of belonging.

Wearing his people’s traditional headdress, Will George, of the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation, screams out his frustration at the Canadian government for allowing the expansion of another destructive oil pipeline across his people’s ancestral lands.

Over the years I have observed that irrespective of culture and our place within the world, the path to true fulfillment often lies in finding joy and meaning through purpose. Living a life of purpose may mean intentionally raising your children wholeheartedly as compassionate, courageous citizens, of planet Earth, or it may mean developing your unique skill or talent so that you can contribute to your community. For me, it is the feeling that my passion lines up with what the world needs. Regardless, it is about recognizing your own inner value.

Seeking shelter from the relentless sun, I was invited in by this beautiful Antandroy woman, who was wearing a traditional mask made of powdered bark, a natural mosquito repellent and sunblock. She too was feeling unwell and I was moved by her humble hospitality and grace.

I marvel at how when we treat one another with compassion, and respect the creatures and land we rely on, our sense of personal nourishment grows in direct relationship. The elements that make up enoughness help us cultivate fulfillment from within. Rather than needing or expecting the world to give us something, enoughness naturally inspires us to give back, to others and to the planet. Cultivating a sense of belonging, embracing spirituality, and intentionally finding purpose. Tapping into existing sacred ecologies and embracing our natural gifts for creative expression. This is how we can nurture enoughness, as individuals, and as an intimately connected global community.

In northwestern Yunnan, each village has a sacred forest where the locals believe the gods reside, along with the spirits of their ancestors. People are not allowed to cut down trees, but they can collect fallen branches, mushrooms, and medicinal plants.

Enoughness is the feeling of something central being restored. It is a luminous path to a fully expressed life.

What a joy it has been to find the purposeful focus of living from enoughness in my own life; by looking carefully and listening closely to the lessons shared with me by the people who still live close to the land and who know how to carve a living from the Earth without destroying it.

The embodiment of strength, knowledge, and the rich cultural heritage of her people, who have lived in the rainforests of Brazil for millenia, this Kayapó elder is a leader in her community and a proud keeper of their traditional knowledge.

Eyes on the horizon, Miracle, Virtuous, and Heavenly Kaahanui float with their surfboards, waiting for the next set of waves to roll in. For centuries their ancestors have practiced this art, perfecting their prowess in the water, and nurturing a deep connection with the life-giving grace of the sea. In that moment, soaked in the glittering spray of the vast Pacific Ocean once again, I know for certain that long-lasting change will only come when we feel more connected to the surge of life that is beating on our shores.

Three Hawaiian sisters wait for the waves in Makaha Beach, Oahu.

Over millennia, the tireless swing of the tides has given shape to the continents and character to our coasts; morphed and bent to the will of the sea. Every day, for a few precious hours, the shore belongs to the land. Then under the gravitational spell of the moon, it is once again reclaimed by the waves. To us, however, it never truly belongs.

There is an invisible line between the familiar feeling of our feet on solid ground and the inky abyss, often foreign and fearsome, where creatures with gills, scales, and fins are better suited to survive.

[1] A curious Stellar sea lion in the rich waters of the Salish Sea. [2] Molina Dawson, a young Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw warrior, is occupying the polluting open-net fish farm that was placed in her people’s ancestral territory without their consent.

Though bound to the land, humans have benefited from the riches of the sea since the beginning of time. We should know by now that if our oceans thrive, so do we. Why then, are we collectively failing to nurture and protect the cornerstone of all life on Earth?

As he lifts his eyes to the falling snowflakes, Naimanngitsoq Kristiansen, a traditional Inuit hunter from Greenland, reminds me that nature is a spiritual sanctuary, made all the more hallowed by the first flurry of snow in Spring.

Knowingly or not we have abused the generosity of the sea. Perhaps we have been walking on land for so long, we have forgotten that our very existence depends on a healthy ocean. Every second breath we take comes from the sea; the oceans are the watery lungs of our planet, producing vast amounts of oxygen and absorbing countless tons of carbon dioxide.

One billion people, including many of the world’s poor, rely on fish for their daily protein. The rain and snow that falls over distant mountains, irrigating fields many miles from the shore, originates at sea. Immense ocean currents regulate our planetary climate, maintaining the perfect conditions for our fragile existence. Today, human-induced global warming and exploitation of our environment are threatening to destabilize all of this.

On a three-week long expedition from the southernmost tip of India to Chennai, I stopped in every coastal town to see what the fishermen were bringing in. The women I met told me that the fish are getting smaller and smaller, and many species are disappearing.

HOWEVER, ALL IS NOT LOST. WE STILL HAVE TIME TO NURTURE THE OCEAN’S INCREDIBLE RESILIENCE.

From Mexico to the Pacific Northwest, I have witnessed entire ocean ecosystems spring back to life when local communities are empowered to sustainably manage and restore their waters. Slowly but surely, communities around the world are harnessing the political will necessary to bring our oceans back to health. When we act together, we can inspire great change. This is why I co-founded SeaLegacy with my life partner, Paul Nicklen.

Zah, an artisanal fisherman, harpoons fish in the Abrolhos Reef to feed his family. Because they live in a Marine Protected Extractive Area, fishermen like Zah are committed to complying with fishing regulations and no-take zones, which benefit their local ecosystem.

With a mission to create healthy and abundant oceans for our planet, SeaLegacy is a strong, collective voice of organizations, social media influencers and individuals working together to spark the kind of global conversation that inspires people to act. Through powerful media and art we deliver hope — the kind of hope that empowers and generates solutions. Hope can be a game changer, and hope for our planet is empowering.

I watched as the sun dipped below the horizon, and the molten gold of sunset saturated the twilight. Just as his ancestors have done for centuries before him, Naimanngitsoq Kristiansen waits patiently for harp seal or walrus at the ice edge.

Extraordinary opportunities exist to restore and thoughtfully develop our oceans in order to protect them and sustain life on this planet.

Our team at SeaLegacy works with an international council of experts to identify projects that are helping to create healthy and abundant oceans. We engage a groundswell social audience of over six million followers with compelling storytelling and invest in community-centered solutions, rallying global support through our massive media network.

Through vibrant digital campaigns, we take on projects such as influencing policy makers to protect whale habitats in the Norwegian fjords, filmmaking to show the critical ecological value of keeping the Antarctic Peninsula wild and free, and partnering with indigenous First Nations communities to ban harmful fish farming in northern Vancouver Island, Canada.

Every day, through our vital work, I experience hope in action. Co-founding SeaLegacy gifts me with the ability to align the rich elements of enoughness with my deep concern for life beneath the thin blue line of our ocean.

From the air we breathe, to the food we eat, to the climate we live in, we all depend on our oceans. Today, they are more important than ever. Healthy oceans absorb vast amounts of carbon from our atmosphere and help reduce the impact of climate change.

On nights when the opalescent moon brings waves crashing against the rocky shoreline of the coast that I call home, I rejoice in the pungent scent of saltwater. The sea is like a forgotten womb from which all life emerged. It is here, at the water’s edge, that my heart beats its loudest.

Perhaps it is the reassuring cadence of the tidal rhythms or the way that the waves roll in from the open ocean with playful, operatic grace, carrying dreams of faraway underwater kingdoms. Or perhaps it is the way that the ocean’s low, sacred rumble rests in my soul, long after the last grain of sand has washed from between my toes.

A shimmering sunset is reflected in these shallow waters, as traditional Vezo fishermen draw up their boats for the night.

As a photographer, I feel an urgency to remind my fellow humans that our destiny is inexorably tied to the fate of the sea. As a scientist, I am motivated by the knowledge that continuing to ignore the failing health of our oceans now, while we ponder the consequences later, is an invitation for disaster.

Combining the two, I am a fierce advocate for our planet and strive every day to make a tangible difference. With hope as a beacon, my dream is that together we can turn the tide and achieve healthy, abundant oceans for all.

Two young Vezo girls, like water nymphs more at home in the ocean than on land, gather fish for their family’s dinner.

CRISTINA MITTERMEIER is a photographer, writer and conservationist documenting the intersection of wild nature and humans. Co-founder at SeaLegacy.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA

Video: Antarctica's Natural Wonders

The video starts in Ushuaia, Argentina and transitions to Port Williams, Chile, then rounded up Cape Horn and crossed the Drake Passage towards the Melchior Islands in Antarctica. The videographers spent 16 days in the Antarctic and got to experience the most amazing scenery and wildlife before they returned back to Ushuaia.

Abstract Australia from Above

“The real voyage does not consist in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” — MARCEL PROUST

Islands on natural salt lake, Lake Johnston, north of Esperance, in Western Australia. (Taken 2014)

I have been attracted to the Australian landscape because of its size and subtle differences — a sense of wonderment, how it all came about, the evolution of the landscape. Like the rest of the world it has gone through many stages to be what it is today — uniquely Australian. But it also is a very old landscape. It is the flattest and driest continent, which compared with other countries, does not manifest itself in grandeur as we know it; large rivers, large mountains and the dramatic changes of the seasons.

The Pinnacles. Limestone formations, Nambung National Park. (Taken 2009)

However, I found that by looking at the landscape from the air, many natural characteristics revealed themselves much better, showing the evolution and the geographical variations. Nature is a great teacher. Observing and experiencing it can stimulate our creative senses which in turn is beneficial to ourselves and our environment.

Pink Lake, north-west of Esperance, Western Australia. This is the natural colouration of the salt lake. (Taken 1988)

It was in 1955 that I bought my first camera, and this was the beginning of a long association with photography. Intrigued by the unusualness of the Australian landscape, I became a landscape photographer with a strong bias for aerial photography, which I felt captured the vastness of the outback best — each flight became a flight of discovery.

Late light on a drifting sand dune, Windorah, south east Queensland. (Taken 1994)

There are so many Australian landscapes worthy of consideration whether they be rivers, coastal plains or deserts — all of which vary seasonally and at different times of the day. As much as possible I like to be inspired by what I see and this is where I experience a sense of wonderment of a world so complex, varied and beautiful.

Coastline between Esperance and Cape Arid, in Western Australia. This shows the reflection of the clouds in the lake, with the beach and ocean in the foreground. (Taken 2006)

Of course there are many ways to appreciate the landscape. My own involvement is to photograph the highlights and to interpret them with the camera in a painterly way. I emphasise these highlights by pointing the camera down and focussing on the subject, excluding the horizon so one looses a point of reference and the reality often takes on an abstract view. I hope that the character of the subject is enhanced and that it reveals more through isolation by the camera angle.

A turkey nest dam near Newdegate, Western Australia, contrasts against the ploughed fields. (Taken 1994)

The aerial point of view also allows us to examine the impact of humanity on Earth. There is a beauty in the man made landscape which takes on a relationship beyond the form as we know it. Certain subjects such as mining dumps, industry and farming look mundane at ground level, but from above my eye begins to recognise a gratifying order in the chaos — crops, paddocks and ploughed fields become masterpieces in abstraction often unknown to their creators. Simultaneously, the aerial perspective can also indicate the abuse and destruction that has taken place.

Salt lakes surrounded by wheat fields, 50 kilometers north east of Esperance, Western Australia. (Taken 1994)

At all times, I take a very personal approach to my work, but I also take great care to retain the optical reality. There are a million pictures out there. I am the only limitation. I can tune in and absorb the reality of the variations, combined with my way of seeing and my attitude. The older I get the harder it becomes, and the more I am drawn to nature. It is the creation of all life and matter that appeals to me now. Maybe I can make a small contribution to its well being which is in jeopardy. If beliefs in eternity are formed, nature is a great catalyst. I often feel intimidated by a great outback landscape, but also inspired by it.

Forrest River, Kimberley, Western Australia. A tidal river system, north-west of Wyndham. (Taken 2003)

We now have more technical gadgetry at our disposal and there is no doubt it can help us to get a better photograph. But that in itself means little unless it enhances our understanding of the world around us. It is more important to use our creative spirit and gain wisdom than purely use it as a tool. Today in our digital age we have Photoshop with its possibility to enhance or to completely distort or create our own image using photographic components. We have become so image conscious that we often forget the beauty of reality.

Ocean between Ningaloo Reef and Coral Bay, Western Australia. The blue variation is due to the ocean’s floor level. (Taken 2006)

The subject of photography can either be concrete or intangible. In the first case the picture is basically realistic, where as in the latter case it is essentially abstract. But what makes photography so interesting is that by combining both we can introduce creativity in the subject and have the best of both worlds.

Ant clearings approx. 4–5 metres across, Great Sandy Desert, Pilbara, Western Australia. (Taken 2003)

Although many photographers can take photographs and do it well, it is work done in the full utilization of that creative spirit that stands out. It should be influenced by the subject itself and come from within oneself.

Tidal variations result in a coastal river pattern, Northern Territory. (Taken 2004)

“I still can’t find any better definition for the word Art, than this. Nature, Reality, Truth, but with a significance, a conception, and a character which the artist brings out in it and to which he gives expression, which he disentangles and makes free.” — VINCENT VAN GOUGH

Lake Dumbleyung, Wagin, Western Australia. Affected by farming this natural lake has become saline. After the first rains, it turns pink. (Taken 2005)

We do not always appreciate the aerial point of view. People regard the landscape as something you fly over. But in reality it is an opportunity to see the landscape from a different perspective. I never cease to marvel at the natural variations in the Australian landscape and although I value what is there photographically, in the end it is the observation and appreciation of the diversity that is the reward.

Top of Curtis Island, Cape Capricorn, north-east of Gladstone, Queensland. An estuary with sand banks. (Taken 1997)

Postscript — All of my photographs are as seen from the air and are not manipulated. I feel that the beauty, colours, and uniqueness of the Australian landscape is complete and needs no enhancing.

RICHARD WOLDENDORP is a Dutch-born Australian landscape photographer, with a focus on the aerial perspective. Appointed the Order of Australia in June 2012, “For service to the arts as an Australian landscape photographer.”

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA

Bissu, or transgender priests, are one of five genders recognized by the Bugis. Reuters

What We Can Learn From an Indonesian Ethnicity that Recognizes Five Genders

On June 13, when a judge in Oregon allowed a person to legally choose neither sex and be classified as “nonbinary,” transgender activists rejoiced. It’s thought to be the first ruling of its kind in a country that, until now, has required that people mark “male” or “female” on official identity documents.

The small victory comes in the wake of a controversial new law in North Carolina that prevents transgender people from using public restrooms that do not match the sex on their birth certificates.

The conflict rooted in these recent policies is nothing new; for years, people have been asking questions about whether the “sex” we are born with should dictate things like which public facilities we can use, what to tick on our passport application and who’s eligible to play on particular sports teams.

But what if gender were viewed the same way sex researcher Alfred Kinsey famously depicted sexuality – as something along a sliding scale?

In fact, there’s an ethnic group in South Sulawesi, Indonesia – the Bugis – that views gender this way. For my Ph.D. research, I lived in South Sulawesi in the late 1990s to learn more about the Bugis’ various ways of understanding sex and gender. I eventually detailed these conceptualizations in my book “Gender Diversity in Indonesia.”

Does society dictate our gender?

For many thinkers, such as gender theorist Judith Butler, requiring everyone to choose between the “female” and “male” toilet is absurd because there is no such thing as sex to begin with.

According to this strain of thinking, sex doesn’t mean anything until we become engendered and start performing “sex” through our dress, our walk, our talk. In other words, having a penis means nothing before society starts telling you that if you have one you shouldn’t wear a skirt (well, unless it’s a kilt).

Nonetheless, most talk about sex as if everyone on the planet was born either female or male. Gender theorists like Butler would argue that humans are far too complex and diverse to enable all seven billion of us to be evenly split into one of two camps.

This comes across most clearly in how doctors treat children born with “indeterminate” sex (such as those born with androgen insensitivity syndrome, hypospadias or Klinefelter syndrome). In cases where a child’s sex is indeterminate, doctors used to simply measure the appendage to see if the clitoris was too long – and therefore, must be labeled a penis – or vice versa. Such moves arbitrarily forced a child under the umbrella of one sex or the other, rather than letting the child grow naturally with their body.

Gender on a spectrum

Perhaps a more useful way to think about sex is to see sex as a spectrum.

While all societies are highly and diversely gendered, with specific roles for women and men, there are also certain societies – or, at least, individuals within societies – who have nuanced understandings of the relationship between sex (our physical bodies), gender (what culture makes of those bodies) and sexuality (which kinds of bodies we desire).

Indonesia may be in the press for terror attacks and executions, but it’s actually a very tolerant country. In fact, Indonesia is the world’s fourth-largest democracy, and furthermore, unlike North Carolina, it currently has no anti-LGBT policy. Moreover, Indonesians can select “transgender” (waria) on their identity card (although given the recent, unprecedented wave of violence against LGBT people, this may change).

The Bugis are the largest ethnic group in South Sulawesi, numbering around three million people. Most Bugis are Muslim, but there are many pre-Islamic rituals that continue to be honored in Bugis culture, which include distinct views of gender and sexuality.

Their language offers five terms referencing various combinations of sex, gender and sexuality: makkunrai (“female women”), oroani (“male men”), calalai (“female men”), calabai (“male women”) and bissu (“transgender priests”). These definitions are not exact, but suffice.

During the early part of my Ph.D. research, I was talking with a man who, despite having no formal education, was a critical social thinker.

As I was puzzling about how Bugis might conceptualize sex, gender and sexuality, he pointed out to me that I was mistaken in thinking that there were just two discrete sexes, female and male. Rather, he told me that we are all on a spectrum:

Imagine someone is here at this end of a line and that they are, what would you call it, XX, and then you travel along this line until you get to the other end, and that’s XY. But along this line are all sorts of people with all sorts of different makeups and characters.

This spectrum of sex is a good way of thinking about the complexity and diversity of humans. When sex is viewed through this lens, North Carolina’s law prohibiting people from choosing which toilet they can use sounds arbitrary, forcing people to fit into spaces that might conflict with their identities.

SHARYN GRAHAM DAVIES is an Associate Professor of Social Sciences at Auckland University of Technology.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON THE CONVERSATION

Swimming with Whale Sharks in Mexico: Ecotourism or Exploitation?

Whale Shark ecotourism in Cancun, with tour companies recruiting the very fishermen who killed sharks in the past as tour operators working toward their preservation.

Read MoreLights of the Medina

This video depicts the famous medinas in Marrakesh, Morocco. The medinas are huge hubs of commerce for locals and tourists. Every sort of product can be found in the medinas, such as food, clothes, souvenirs, performances, etc.

Read MoreIn Season 3 of ‘Parts Unknown,’ Anthony Bourdain took viewers to Tanzania. CNN

Anthony Bourdain’s Window into Africa

Anthony Bourdain might have been a celebrity chef, but viewers of his Emmy Award-winning travel show, “Parts Unknown,” didn’t tune in for curry and noodle recipes.

Cooking was simply the conceit Bourdain used to have a conversation about the culture, politics, struggles and triumphs of people around the world.

As a human geographer, I was drawn to how Bourdain upended the travel show genre, telling compelling and complicated stories about people and places most Western viewers tend to view through a lens of simplistic stereotypes or caricatures.

Even more remarkable, his work wasn’t relegated to obscurity. The show aired on CNN – a mainstream cable outlet with millions of viewers.

I was especially interested in the way the show depicted Africa, a continent Western media tends to portray using what novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie famously called a “single story” – a monolithic narrative of poverty, backwardness and hopelessness.

So in a paper published last fall, I analyzed Bourdain’s Africa episodes, which took viewers to Congo-Kinshasa, South Africa, Tanzania, Madagascar and Ethiopia.

In them, he largely rejects the “single story” approach taken by much travel writing, and later travel television, since at least the 16th century. While the stories told about Africa in the West have changed over time, they’ve often lacked nuance and multiple voices – something Bourdain was eager to provide.

A ‘single story’ of horror and hopelessness

In the imaginations of many Westerners, Africa exists as a silent, docile, set piece – a contrasting “other.”

Sociologist Jan Nederveen Pieterse notes that for centuries – through deliberate lies and well-meaning mistakes – travel writers, missionaries and popular media outlets have wrongly depicted Africa as a place devoid of civilization, a frontier of wilderness and savagery.

The dominant narrative goes something like this: If the West is stable, Africa must be chaotic; if the West is mature, Africa must be infantile; and if the West is technologically advanced, Africa must be primitive.

Reality television and travel shows often deploy these tropes. Cultural anthropologist Kathryn Mathers has written widely on media depictions of Africa, suggesting that programs like “Survior: Africa” and Nicholas Kristof’s popular newspaper columns tell predictable stories of poverty and chaos with little effort to contextualize them within a larger history.

The dynamic voices of Africans – hardly a monolithic category – are often absent in these narratives. In the rare event they do appear, they’re often presented as people without politics who exist only to welcome tourists and protect rhinos. Intrepid conservation officers and overburdened health workers are favorite characters, along with the traditional leader, the street vendor and the small child in school uniform.

Cable news coverage of Africa also tells a “single story.” As Mathers wryly notes, when the continent does get coverage, the stories can be distilled down to the same topic: “the horrors of the hopeless continent, as seen on CNN.”

Bourdain’s critical lens

But Anthony Bourdain was also “seen on CNN.”

Beginning with his memoir, “Kitchen Confidential,” Bourdain built his persona as a speaker of unspoken truths. Likewise, he steered his travel show to “parts unknown” – or, more accurately, parts only known through incomplete tropes.

In each episode, Bourdain gives a brief historical overview to remind the audience that places are made by their histories. He doesn’t gloss over the difficult ones. For example, when explaining contemporary Congo, he implicates his American viewers:

“When the new country managed to inaugurate their first democratically elected leader, Patrice Lumumba, the CIA and the British, working through the Belgians, had him killed. We helped to install this miserable bastard in his place: Joseph Mobutu.”

When Bourdain is in Madagascar, he reflects on his own conflicted relationship to tourism and colonialism.

In Season 6, Ethiopian-born, Swedish-raised chef Marcus Samuelssonjoins him in Ethiopia. Together, they explore the theme of home in the context of the African diaspora.

While one might criticize Bourdain’s perspectives, he could never be accused of taking a sanitized, apolitical approach.

In the episode on Tanzania, he visits a Maasai village – a common pit stop for travel shows about East Africa. But “Parts Unknown” rejects the stereotype that the Maasai are an isolated, backwards tribe that exists apart from the modern world.

When a villager learns that Bourdain was born in New Jersey, he tells the host that his son attends university there. The conversation picks up again later in the episode, when Bourdain and the Maasai man thoughtfully ponder globalization and the anxiety and opportunity of social change. Bourdain understands that his African hosts aren’t anchored to a static past. Instead, they are dynamic actors in a global economy.

Bourdain writes his own reflections into each script. In Madagascar, Bourdain reminds viewers that

“the camera is a liar. It shows everything. It shows nothing. It reveals only what we want. Often, what we see is seen only from a window, moving past and then gone. One window. My window. If you had been here, chances are you would have seen things differently.”

The episode then cuts to previously rolled footage but reedited in the style of Mathers’ “horrors of the hopeless.” It’s all done to show the ease with which dominant narratives are packaged and to emphasize that “Parts Unknown” seeks to convey something entirely different.

The greatest strength of “Parts Unknown” was its comfort with unknowns remaining unknown – its resistance to arriving at singular truths about complex places. Bourdain never claimed that the “artifice of making television” – as he called it – allowed more than “one window, his window.”

Yet it was an open window, a critical lens that helped his large audience disentangle the tropes so often served up by popular media. Bourdain was critical of the single story, critical of widely held stereotypes and perhaps most critical of his own position as a masterful storyteller.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY POSTED ON THE CONVERSATION

Inside an Apache Rite of Passage Into Womanhood

For the Mescalero Apache Tribe, girls are not recognized as women until they have undergone the Sunrise Ceremony- an ancient, coming-of-age ceremony that lasts for four days. Last May, VICE got rare access to the ceremony for Julene Geronimo - the great, great grand-daughter of the renowned Apache leader, Geronimo. We followed Julene through each day of her arduous rite-of-passage to better understand what womanhood means for the Apache tribe, and how these ceremonies play a significant role in preserving a way of life that almost became extinct.

A World Cup for the Overlooked

CONIFA Offers a Humanitarian Alternative to FIFA.

Conifa World Cup, Group C, Padania v Székely Land, Bedfont Sports Centre, London/England. By Ungry Young Man from Vienna, Austria. 3 June 2018. Photo Credit: Confifa

Soon, the eyes of the world will be on the FIFA World Cup. There will be all the usual pomp and spectacle, feats of athleticism, and celebration of unity. And yet, FIFA’s large-scale corruption is no secret to fans and players alike. Recurring scandals have tainted the name of soccer’s governing international organization, culminating in the arrest of seven top officials for claims of corruption in 2015. But FIFA also has a somewhat less known history of excluding the many teams that do not meet its participation requirements. To play in FIFA, the team’s nation must be recognized by the international community, and only one football team from each country is allowed to participate.

In 2013, the Confederation of Independent Football Associations, otherwise known as CONIFA, was formed with the intention of providing a world stage for these unrecognized teams to compete on. In a poetic opposition to FIFA, CONIFA was founded as a non-profit and represents teams comprised of people without a state, unrecognized nations, minorities, people who prefer representing their cultural identity over country of birth, and anyone else who cannot, or prefers not to meet FIFA’s requirements. CONIFA now includes 47 member teams and represents 334 million people worldwide. “We have nothing against FIFA,” CONIFA General Secretary Sascha Düerkop told the press shortly before the opening of the CONIFA World Football Cup, “They are very great to learn how not to do things.”

The 2018 CONIFA World Football Cup opened on May 31 in South London, and was hosted by the London-based Barawa team of Somali refugees. Among those represented at the cup was the Pandania team, comprised of players from eight different regions of northern Italy, and winners of the past two CONIFA European Football Cups as well as ending fourth in the 2016 World Football Cup. Another notable team is Abkhazia, the former title holders representing their semi-recognized Eastern European state. Representing Matabeleland, a war-torn area in western Zimbabwe, are the Warrior Birds, who successfully raised the 25,000 dollars necessary to make the trip to England entirely through crowd funding and selling jerseys. “No one ever believed we would make it to London but we made it,” said captain Praise Ndlovu, “I'd like to say thank you to everyone.”

The final match of game was between Northern Cyprus, a state recognized only by Turkey, and Karpatalya, representing the Hungarian minority in Ukraine. While in the end, Karpatalya won the match 3-2, CONIFA is about more than just winning, it’s about inclusivity, about allowing everyone to participate on the world stage.

“As long as FIFA has existed, there has always been a non-FIFA world of teams who want to play on a global stage but can’t for a variety of reasons,” Per-Anders Blind, the president of CONIFA, told The New Yorker. “What we have done is fill a gap, a white spot on the map that nobody cared about.” CONIFA represents a more honest, somewhat purer version of football, which has returned to FIFA’s original intention of supporting the world-wide football community and organizing truly international competitions.

EMMA BRUCE is an undergraduate student studying English and marketing at Emerson College in Boston. She has worked as a volunteer in Guatemala City and is passionate about travel and social justice. She plans to continue traveling wherever life may take her.

Winds from Morocco

This video captures scenes in Morocco ranging from the deserts to the cities.

Read MoreWakhan, An Other Afghanistan

Journeying through a remote region of northeastern Afghanistan, untouched by the war and preserved from the Taliban regime, this story pays tribute to the ancient culture of this land, which has never disappeared but which has simply been forgotten.

This narrative serves as an introduction to my multi-platform project, ‘Wakhan, an other Afghanistan’. One of the photos from this project won first prize in the 24th annual National Geographic Traveler Photo Contest, and the 78-minute film ‘Wakhan’ was selected as one of the firm favourites to feature in the Etonnants Voyageurs Festival in St-Malo, France.

My mind takes me back to 8 August 2011. It must have been around 2 o’clock in the afternoon, but in any event, time here takes on an alternative dimension, something which we have been discovering and settling into since the beginning of our journey.

Then I remember a young Afghan saying to me a few weeks earlier, “You have your watches, and we have the time.”

Under the arborescent canopy of a small shelter made with stones and yak excrement, Fabrice and I wait for our hosts to bring us bread and tea, which has been our sole source of nutrition morning, noon and night for more than three weeks. Dates, energy bars, dried fruit — these are a thing of the past, and I have already lost 15 kilos.

We had planned ahead with two people in mind, forgetting on market day at Ishkashim — the village on the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan — that we would be accompanied by one guide or several for this expedition along the Wakhan Corridor, as far as China.

We travel for a month in the company of Amonali and Souleman, two Ismaili Wakhis of twenty-four and thirty-two years of age, who are taking care of our horse and our donkey. A last-minute addition to the group is QuarbonBek, a twenty-year-old Sunni Afghan and real ‘city boy’, who we have picked up at Ishkashim to fill the role of interpreter.

After the first week of hiking across the Hindu Kush at 3,500 to 5,500m above sea level, we have exhausted all our supplies, and from now on we have to satisfy ourselves with the low-calorie diet of bread and tea with yak milk which is provided — and which we can buy — in every village. We have chanced upon small quantities of rice here and there, and then three days ago some lamb for the first time, which has ended up making us all ill, as if our bodies were rejecting the meat.

Humbly and respectfully we have been adapting for three weeks to the local diet, experiencing firsthand the process of survival to which all these families remain inextricably bound. Every encounter and every meal reminds us that in this region, which fully awakens the senses and intensifies the emotions of the traveller, life expectancy stops short at 50 and the infant mortality rate verges on 60% — the highest in the world.

We pause for several hours in one of the villages situated along the Corridor ‘high route’ that is the pathway for the return journey, making a transition from the lands of the Khirghizes to Wakhi territory. From Ishkahim to Erjhail — one of the last of the Corridor villages to border with China — we will probably walk more than 450 kilometres over the course of 30 days, following in the footsteps of Marco Polo and Alexander the Great in crossing the entirety of the Wakhan Corridor.

Our horse carries the rucksacks, tent, sleeping bags, camping stoves and gas cylinders, as well as the few additional clothes we have — outer-layers, rather than spare garments — while our donkey is loaded with 40 kilos of photo, video, sound and IT equipment, wrapped in two flexible solar panels, an essential for recharging all the batteries in a region which we assume to be completely without power.

Yet to our astonishment, the Khirghizes — a nomadic people of Mongolian aspect, the last remaining descendants of Genghis Khan, living on the highest plateaux of Wakhan, several weeks’ walk away from any of the main Pakistani, Afghan, Tajik or Chinese villages — have solar panels, satellite aerials, television sets, and an impressive array of batteries, cables and chargers. And when Oji Ossman, the chief Kyrgyz in the village of Kashch Goz, produces a mobile phone from his military jacket — even though obviously there is no network coverage — in order to take our photograph, all our assumptions about these tribes, the idea that they are still leading the lives of their ancestors, seem absurd and unfounded.

People in this part of the world are undoubtedly feeling the effects of new technology, a process triggered by the exchange of goods.

The Wakhan Corridor, as part of the Silk Road, has been established for centuries as a route for traffic and trade of all kinds. Pakistanis, Afghans and Tajiks still spend weeks at a time traversing the mountains, on foot or on horseback, to purchase from the Khirghizes the herds of yak, goats and sheep which have always been at the root of their livelihood.

We shared the guest yurt in KashGoz with three Pakistani herdsmen, who had come from the Hunza Valley with the intention of obtaining a herd of goats in exchange for a television satellite aerial, several solar panels, and some sacks of rice and flour.

In Erjhail, we encountered Ramine and his brother, two young Afghans who had walked in excess of four weeks from Kabul to buy around one hundred goats and ten yaks from the village chief. We would go on to spend two days in their company before travelling together for several days on the journey home, until our paths went their separate ways.

As always, the looks we attract from the four herdsmen in the Wakhi village perched high in the mountains, where we rested for a few hours, are benevolent, but also perplexed. They are asking themselves, “What are these two strangers doing here?” “A report about us” is the most likely answer from Souleman, pointing out with his finger the camera and video equipment placed on a piece of cloth on the ground.

Of course, we are the foreigners, the exotics — and sometimes even the object of complete incomprehension. “Why do they come and live like us in such hardship?” is the feeling we often detect in our conversations.

Our hosts frequently thank us for coming to meet them and for taking an interest in their lives. Repeatedly we feel the sadness in their gaze as they watch us leave again. I have the feeling that they are somehow counting on us from the moment we are welcomed.

We are now in a relatively advanced state of physical and mental fatigue, and the distance separating us from each other is immense. Throughout the whole journey we have felt ourselves connected, part of a shared experience and a brotherhood.

But at this exact moment, our facial expressions and the breakdown of our appearance betrays the disconnection. Even though we know exactly where we are on the topographical map, in our heads it is the first time that we are feeling so distant, maybe even lost?

Considering the original motivation behind an experience like this, what have we truly uncovered in the Wakhan? What will we be able to share on our return, and through our photographs?

What stories to tell? There are so many.

At the heart of a journey devoted to documentary, it is the personal and professional questions which confront each other, providing answers and sometimes shedding light on one another. And when I look at Fabrice, who is silent as I am, my companion of days gone by, of this moment and always, I feel myself reconnecting.

There we are, the two of us. We have been searching for something, and only now do we find its presence — a profound sense of humility.

We have never been consciously afraid, neither of the mountains, nor of all that we have witnessed in Afghanistan in more than 20 years, yet the self-knowledge of this moment is deeply reassuring.

Because if I ever shut down — something which I feel capable of right now — he will be there to restore me. By shutting down, I mean cutting the cord, and no longer being able to endure the weight of escalating hardship, a burden which grows hour after hour, days and weeks on end.

As a humanist, it pains me to see so many men, women and children living under such extreme conditions, and myself unable to endure any longer the psychological torture of knowing that the next bit of potato or piece of fruit is a mere three weeks walk away.

Have we become psychological prisoners of our own investigation? I watch Souleman, crouched down opposite me. This young man, who seems ten or fifteen years older than his thirty, is smiling, supporting me now as he has done for the last three weeks, in such a way that with every gesture I make, I can feel his watchful presence.

I cannot allow myself to betray the trust he has placed in us both, since the start of this journey, and which we feel on so many levels.

I sense that it is not just the traveller that this young man is supporting and protecting, but also the writer, who has promised, with all his photographic and cinematic recording kit, to uncover to the rest of the world his very existence, that of his loved ones and of his community as a whole. We cannot afford to show any sign of weakness.

So when the bread and tea are eventually served, bringing us back to our senses and to the harsh reality, I look at Souleman and smile at him in my turn. Through this knowing smile, a mutual promise is made.

He will keep me safe and sound until the end of my journey, and I will pay homage on our return to all those we have encountered, opening the world’s eyes to an other Afghanistan, which has never disappeared but which has simply been forgotten.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA

VARIAL CÉDRIC HOUIN is a photographer, creative director, writer, explorer, seeker. He has put his artistic chops in the service of the planet.

Wild Africa

Leaving the urban setting and modern life behind, for 15 years I have been privileged to travel through some of the wildest regions left on our planet — compelled to capture the unique personalities and expressiveness of the magnificent wild animals of Africa. All in black and white, all part of one big family album.

My first meeting with Africa was like a thunderbolt.

There was a part of me that wanted to return to our roots, and Africa resonated with me like the animal instinct that lies deep within each of us. After travelling for thousands of miles, I always have this incredibly vibrant feeling of being in entirely unknown territory. Africa is always evolving, free, and wild... hugely wild.

Above: Lioness (2015)

Above: Hugs of lioness (2006)

Utterly disconnected from our urban environment, for more than fifteen years I have been drawn — mind, body and soul — to photograph the remarkable animals from this land of light and contrast.

Above: Cheetah before the rain (2006)

Above: Elephants and bird (2015)

I am constantly inspired by the sense of serenity and harmony between the natural landscapes and the diverse wildlife that roams these lands.

Everything is connected and the animals are totally adapted to their environment. I take photographs based on my gut instinct. For me, the thing that matters the most is the connection.

Above: Elephant, The road is closed (2015)

Above: Elephant crossing the river (2009)

I cannot stand strict pre-visualisation or procedures that lock people into pre-formatted ways of work. My conviction is never to prepare my shots. I prefer to be guided by luck, and to be inspired by the ever-changing spectacle of wildlife. Out in the field, I often work with a local guide who will drive the car while I concentrate on taking photos. It is very important to be utterly present in the moment, and not to be disturbed.

Opportunities in wildlife photography never come twice.

Above: Zebras crossing the river (2015)

Above: Rhinos quartet (2013)

For me, there is no difference between animals and humans in terms of photography technique. When I take a picture of a lion or a giraffe, I use exactly the same approach as when I photograph people. I try to capture something of the animal’s unique personality and expressiveness, as well as their strength and sense of freedom. I believe my pictures can create a connection between the animal and viewer, as the viewers discover a personality in these animals, and realise they have emotions too.

Above: Lion in the grass (2013)

Above: Two zebras (2004)

Above: Cheetah portrait (2013)

I am always filled with a great sense of tranquility and happiness when I leave the urban setting and modern life behind — travelling for weeks on end through some of the wildest regions left on our planet.

For me, there is nothing more powerful than the strength and beauty of Nature, and yet, at the same time, it is very fragile and precarious.

Above: Elephants crossing the plain (2013)

Above: Giraffe in harmony with their natural setting (2013)

Today, the fall of wildlife in Africa and elsewhere is disastrous.

I cannot know if we will discover more effective methods to halt or reverse this devastating change. However, I choose to hope and believe that we can. I believe that people are fed up with shocking images of destruction, poaching and deforestation — and yet it is of grave importance that we share these images, as we must all know what is happening on our planet. I don’t know exactly how photography can help preserve our wild ecosystems, but I feel proud when people experience my images and understand that these animals are just as ‘human’ as we are — with a personality, and a family.

Above: Lion, The small one (2013)

I believe that we must have a sincere conscience for our fellow animals, and the devastating impact our species is having on so many of them. We must open our minds and hearts to the fact that we all part of a living, breathing planet, and recognise that we are just one piece of this wonder.

We must leave more space, more life, for all the other species, because we will not survive their extinction. It is humanity’s greatest challenge.

* * *

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MAPTIA

LAURENT BAHEUX

I am a self-taught French photographer inspired by the soul of nature and wildlife. I express this only in Black and White, like a big Family Album. www.laurentbaheux.com

TANZANIA: The Last Hunter Gatherers

Hunting only with bows, arrows, and their ingenuity, what marked my time with the Hadza was how remarkably happy they seemed. In their language, there is no word for “worry” and by following their ancestral ways, the Hadza truly live in the moment.

Read MoreThe Origins of Pama-Nyungan, Australia’s Largest Family of Aboriginal Languages

The approximately 400 languages of Aboriginal Australia can be grouped into 27 different families. To put that diversity in context, Europe has just four language families, Indo-European, Basque, Finno-Ugric and Semitic, with Indo-European encompassing such languages as English, Spanish, Russian and Hindi.

Australia’s largest language family is Pama-Nyungan. Before 1788 it covered 90% of the country and comprised about 300 languages. The territories on which Canberra (Ngunnawal), Perth (Noongar), Sydney (Daruk, Iyora), Brisbane (Turubal) and Melbourne (Woiwurrung) are built were all once owned by speakers of Pama-Nyungan languages.

All the languages from the Torres Strait to Bunbury, from the Pilbara to the Grampians, are descended from a single ancestor language that spread across the continent to all but the Kimberley and the Top End.

Where this language came from, how old it is, and how it spread, has been something of a puzzle. Our research, published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution, suggests the family arose just under 6,000 years ago around what is now the Queensland town of Burketown. Our findings suggest this language family spread across Australia as people moved in response to changing climate.

Aboriginal Australia is often described as “the world’s oldest living culture”, and public discussion often falsely assumes that this means unchanging. Our research adds further evidence to Australia pre-1788 being a dynamic place, where people moved and adapted to a changing land.

Map of Pama-Nyungan languages, coloured by their main groupings. Compiled by Claire Bowern using data from National Science Foundation grant BCS-0844550.

Tracing Pama-Nyungan

We used data from changes in several hundred words in different languages from the Pama-Nyungan family to build up a tree of languages, using a computer model adapted from those used originally to trace virus outbreaks.

Different related words for ‘fire’ in certain Pama-Nyungan languages. Green dots show languages with a word for ‘fire’ related to *warlu; white has *puri; red has *wiyn; blue has *maka, and purple *karla. Chirila files (http://chirila.yale.edu) and google earth for base image.

Because our models make estimates of the time that it takes for words to change, as well as how words in Pama-Nyungan languages are related to one another, we can use those changes to estimate the age of the family.

We found clear support for the origin of Pama-Nyungan just under 6,000 years ago in an area around what is now the Queensland town of Burketown. We found no support for the theories that Pama-Nyungan spread earlier.

The timing of this expansion is consistent with a theory that increasingly unstable conditions caused groups of people to fragment and spread. But correlation is not causation: just because two patterns appear related, it does not mean that one caused the other.

In this case, however, we have other evidence that access to ecological resources has shaped how people migrated. We found that, in our model, groups of people moved more slowly near the coast and major waterways, and faster across deserts. This implies that populations increase where food and water are plentiful, and then spread out and fissure when resources are harder to obtain.

You can see a simulated expansion here. The spread of Pama-Nyungan languages mirrored this spread of people.

What languages tell us

Languages today tell us a lot about our past. Because languages change regularly, we can use information in them to work out who groups were talking to in the past, where they lived, who they are related to, and where they’ve moved. We can do this even in the absence of a written record and of archaeological materials.

For places like Australia, the linguistic record, though incomplete, has more even coverage across the continent than the archaeological record does. At European settlement, there were about 300 Pama-Nyungan languages. Because there are at least some records of most of them we are able to work with these to uncover these complex patterns of change.

There are approximately 145 Aboriginal languages with speakers today, including languages from outside the Pama-Nyungan family. Many of these languages, such as Dieri, Ngalia and Mangala, are spoken by only a few people, many of whom are elderly.

Other languages, however, are actively used in their communities and are learned as first languages by young children. These include the Yolŋu languages of Arnhem Land and Arrernte in Central Australia. Yet others (such as Kaurna around Adelaide) are undergoing a renaissance, gaining speakers within their communities.

Nathan B. performing “Yolŋu Land” using English and Yolŋu Matha.

Finally, though not the focus of our study, there are also new languages, such as Kriol spoken across Northern Australia, Palawa Kani in Tasmania, and Gurindji Kriol. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders also know English, and most Indigenous Australians are multilingual.

Without records of all these languages, and without ongoing work to support speakers and communities, we aren’t able to do research like this, and Australia loses a vital link to its history. After all, European settlement of Australia is a tiny chunk of the time people have lived on this land.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

CLAIRE BOWERN

Claire Bowern is Professor of Linguistics at Yale University. Her 2004 PhD is from Harvard University and examined the historical morphology of complex verb constructions in a family of non-Pama-Nyungan (Australian) languages. Her research focuses on the Indigenous languages of Australia, and is concerned with language documentation/description and prehistory.

Tokyo: Random Access Memories

This short film features random shots of Tokyo, offering an artistic perspective of this non-stop city. Shot and edited by Junwoo Lee.

5 Cities That Are Leaders in Sustainable Public Transportation Initiatives

The World Economic Forum released its most recent Sustainable Cities Mobility Index, which ranks some of the globe’s largest metropolises based on both the viability of transport and its relative footprint.

The Index measures factors such as connectedness via public transport, including metros and buses, as well as pedestrian accessibility, ease of use by cyclists, among others. What unites each of the five cities featured here seems to be the overall strategy of incentivizing use of public transport, while disincentivizing the tendency to commute by automobile. In this way, public transportation systems trade on efficiency: by running frequently, integrating renewable energy sources, and maximizing often-limited physical space in the crowded cities, the public transport strategies of each of the cities listed have served to reduce car emissions significantly.

HONG KONG. Named number one on the sustainable mobility index, Hong Kong has constructed an impressive MTR metro system, which is responsible for 90% of residents’ daily journeys. Likewise, the cost of transport in Hong Kong has remained relatively low, permitting accessibility to all residents, further disincentivizing travel by car. In fact, due in large degree to the success of the public transportation system, less than 20% of residents of Hong Kong own a car.

ZURICH. At number two on the list, Zurich has demonstrated a great deal of success minimizing transportation by car, with just 37% of the population owning a car, as well as a little over a quarter of journeys measured occurring by car. The majority of public transportation in Zurich occurs by high-speed light rail, a system widely recognized to be one of the most energy- and space-efficient modes of public transport.

PARIS. In 2012, Paris pledged to reduce travel emissions by 60% within the most populated areas of its city, introducing more networks of pedestrian walkways and bike paths, incentivizing the use of bicycles and electric cars through two new city rental systems, as well as altering delivery systems such that it limits the number of diesel-fueled vehicles driving through the city each day. Parisian city officials have also been working to initiate regular “car-free” days, as well as other measures that promote alternative forms of transport.

SEOUL. Throughout the past decade, Seoul has pioneered a significant number of innovations that promote sustainable mobility. An inefficient highway system has been repurposed to become a large public park with an extensive network of pedestrian causeways. Moreover, Seoul has employed specified bus lanes, which have increased by nearly one million the number of citizens who use the public transport system each day, as opposed to driving. The significantly greater efficiency of public transportation, as well as the ease of access afforded to pedestrian traffic has cut down greatly on the number of citizens commuting by car, one of the most inefficient and least sustainable modes of travel.

PRAGUE. Prague has undertaken the “Tune Up Prague” initiative, just one of a series of sustainable transportation proposals enacted under the 2015 Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan. The “tune up” has focused on increasing foot and bicycle travel through the facilitation of pedestrian pathways. The proposal has also worked to bring accessible, sustainable transportation to all, seeking to bump up the amount of wheelchair-accessible metro stations by 23%, such that 95% of the city’s metro stations are wheelchair-accessible.

In integrating energy and space-efficient public transport with initiatives that promote pedestrian and cyclist travel, the five cities listed above have developed transportation networks that are both accessible and sustainable. Incentivizing public transport increases a city’s ability to experiment with “greener” travel, while simultaneously reducing automobile emissions. The ingenuity of each of the five metropolises provides a crucial example for other major cities, working towards a more sustainable, more connected future.

Hallie Griffiths

Hallie is an undergraduate at the University of Virginia studying Foreign Affairs and Spanish. After graduation, she hopes to apply her passion for travel and social action toward a career in intelligence and policy analysis. Outside of the classroom, she can be found, quite literally, outside: backpacking, rock climbing, or skiing with her friends.

Grandpa Joe, somewhere in the world. Photo by Ethel Ellenbogen.

The Man Who Loved To Travel.

My Grandpa Joe was one of those classically great men. A mensch. Born in the bathroom of his parents’ Temple Street home in downtown Los Angeles in 1917. The family moved around Los Angeles a lot — from downtown to Boyle Heights to Tujunga to Beverlywood. Sticking close to the pockets of other Jewish immigrants who faced daily anti-semitism. In his pre-teen days, he would travel miles by bus to get to school, then travel all the way back to work in his father’s garment factory into the night — the schmata business — learning the machines. Then he’d do his homework. It was clear very early on that he was a standout student and, after skipping pretty much every other grade, he ended up at Berkeley. Apparently, he was in a rush to meet my grandmother, Ethel, who was also at Berkeley. After graduation, they came back to L.A. He also ended up in the garment industry, one of the first to create women’s sporting apparel.

And as great and respect-worthy as that all is, the story of how he made his way in the world was simply a precursor to a just-as-impressive story of how he made his way around the world. Joe’s true passion was travel.

By his retirement, he had also started a small side business as a travel agent. He called it, Love To Travel. He kept himself busy (and his travel deductible) by organizing and sometimes leading tour group in various parts of the world.

By the time I came around, he had already been across the globe a few times — which was in and of itself a pretty exotic feat for the era — but he was only just getting started. Joe and Ethel rewarded themselves for a good life of hard work by spending the second half of it, over thirty years, visiting places all over the world. At least once a year, they would take off — most often in Western Europe, but also Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, South America, Central and Eastern Europe, and probably quite a few more. When they’d return, the family would gather for an old-fashioned slide show. Ethel would prepare a platter of dried fruits and nuts, the screen would go up, lights would go down and the projector would flick on. What proceeded then would be a competition of memory for the small stories and events of their trip. My grandfather’s memory for detail was unassailable, but Ethel always had the last word.

Many years later, after he had died and it was apparent that I would continue the legacy of travel and photo-taking, my grandmother entrusted me with his many boxes of slides. They were highly unorganized and consisted of everything from loose negatives to filled carrousels to small, bulging slide boxes. Thousands and thousands of images. All un-labeled.

It’s taken me fifteen years to get it all together and scanned. I have barely started down the process of trying to figure out where these places are and what year they might have been taken. I may never know. In some ways, it’s not what really matters. I actually quite enjoy the mishmash of time and place that these images, in this scattered format, create. They come together exactly like my memory of him — a richly condensed man of great experience and joie de vivre.

What I love about these images (and this is only a very small taste of them) is that they are there to document the travel as much as the place. His images are heavily aware of being a visitor — in those days, foreign travel had a formality to it. In the images, you can see both the formulaic-ness of tourism but also a man who would climb to any height to get a better view than the crowds. He would do anything for a good shot — I watched him sneakily break off to go take a snap, many times.

I love the raw talent depicted in these photos. A high percentage of them are out of focus, which for me only adds to my appreciation for him. Focusing was hard, in those days — no electronics or fancy in-camera technologies. He learned it all on his own, with no training — and considering that, there’s a side story that develops with these images of a man who was learning a craft from love of subject backwards. Which is also how I learned photography.

My favorite image is one that I don’t recall ever making it into a family slide show. It features my grandmother driving an early 70’s Nova on a foreign beach somewhere. It’s a shocking image for me in so much as she never drove. Usually, Ethel was in the back of a stuffy Cadillac — she suffered from a deep, nearly-disabling anxiety and her overly-dramatic fears made her almost comically over-concerned about every little thing. Seeing her here, carefree and outrageously off-the-beaten-course adds an entirely different look at their relationship and adventures together.

In the end, your photographs should not only show a great life, they should convey what you loved. Enjoy the following story of the man who loved to travel.

Grandma Ethel, in Paris. Photo by Joe Ellenbogen.

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

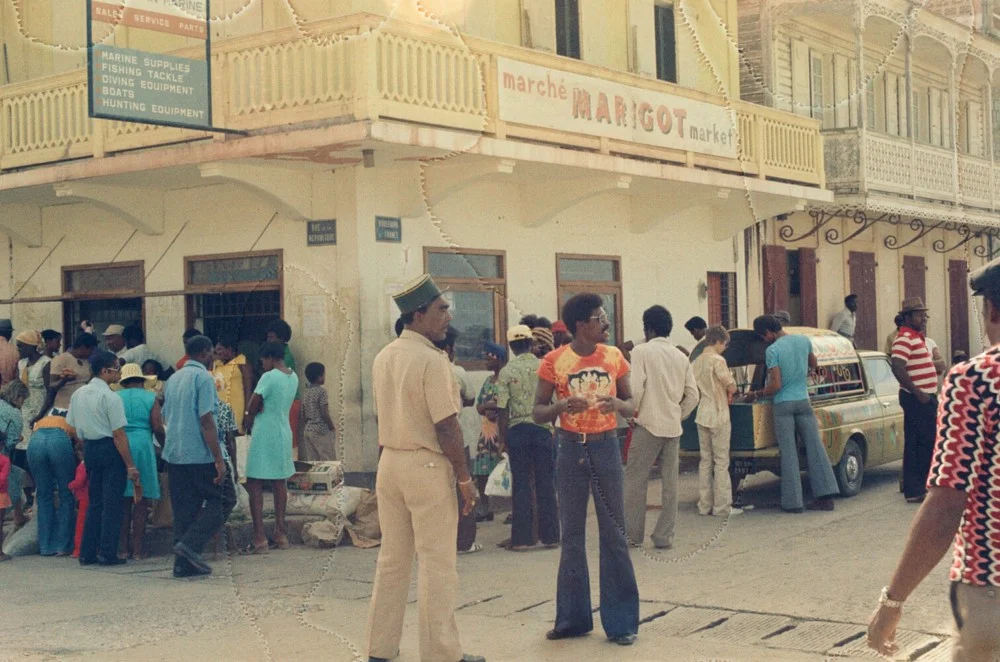

The corner of Rue de la République and Boulevard de France in Marigot, Saint Martin (thank you Richard Hopkins). Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Photo by Joe Ellenbogen

Grandpa Joe, somewhere in the world. Photo by Ethel Ellenbogen.

Thank you for reading. For my own photography, find me at instagram.com/joshsrose

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON MEDIUM.

JOSH ROSE

Journalist, photojournalist, creative director.

How to Enjoy Travel Without Social Media

DID YOU KNOW that if a tree falls in the woods and you don’t post the video to your Instagram story, it still actually happened? I’m aware of the irony of writing about a topic like this on a popular travel website, where, if all goes well, it will be retweeted, shared on Facebook, and maybe even receive a video response on YouTube (please?), but there are ways to enjoy traveling without social media.

Low-tech travel is still an option

Some travelers get the idea that getting offline also means completely cutting themselves off from technology, when in fact a simple reduction will do. Leaving your phone at home and using a calling card to stay in touch may be annoying, but isn’t it worth removing the temptation of snapping a selfie? Just because we no longer live in a world where Polaroid cameras are ubiquitous doesn’t mean they aren’t out there to capture memories. If you use your blog primarily as an outlet for your creativity and not as a form of income, you can try jotting your experiences down on paper. Travel like it’s 1999.

Time goes further without technology

You may not be able to look back on what happened one day ten years ago in Thailand without some digital photographic evidence, but if you spent that time bathing elephants and getting drunk with expats you’re going to remember the experience better without wasting time documenting everything as it’s happening. My weekends in Japan usually fly by when I’m traveling solo and stop to write on my Macbook or scroll through IG on my phone, but when two Couchsurfers came to visit and we spent the whole day talking and exploring, I couldn’t help but appreciate how much longer the days seemed to last. Being mindful during your travels means taking the minute between when your food is served not to find the perfect angle for a picture, but instead reflect on how fortunate you are to have this nourishment in this foreign country with good friends.

Live your life without online feedback

Social media has fundamentally changed how we communicate in many ways, but probably none more than allowing snapshots of our lives to receive immediate feedback from the whole world. We’ve probably all taken a picture of a scene like a sunset over the ocean with the intention of wanting to know want other people think about it, without taking the time to wonder whether we actually like it in the first place.

Your travel experiences have value even if no else sees your picture and gives it a like. Seeing someone’s expression in person and understanding their reaction to your temple stay and spiritual awakening (even if it’s an eye roll) are going to mean more to you than someone writing a cliché comment with an emoji.

Think about where you travel, and why