Kelcie Lee

Behind Hawaii’s Kalaupapa National Historical Park lies a rich history of loss, resilience and compassion now preserved as a memorial site.

Kalaupapa Peninsula on the Hawaiian island of Molokai. Djzanni. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Beneath the Hawaiian island of Molokai lies a rich history of stories that have largely gone unheard. For years, the remote Kalaupapa Peninsula was known for its history of seclusion and suffering, but it has since been transformed into the Kalaupapa National Historical Park, redefining the location for its endurance and charity.

In the mid-19th century, the Kalaupapa Peninsula became the center for those forced into quarantine due to Hansen’s disease, or leprosy, by the Kingdom of Hawaii. During the earliest moments in civilization, leprosy was seen as a contagious, brutal and incurable disease that no one knew how to combat. Unlike our present-day knowledge of health regulations, the only way to stop this disease from spreading was expulsion from society. In itself, the disease attacks the human body’s nerves, leading first to severe damage to the skin or eyes before sores, paralysis, permanent disfigurement or death.

The earliest papers date traces of leprosy in Hawaii as far back as the 1830s. Because of a lack of immunity to a variety of diseases, Hawaiians suffered alarming death rates. As no one knew how to stop this disease, officials were thrown into a state of desperation. In 1865, district justices and police started arresting people who were suspected of having leprosy, which fundamentally worked to criminalize the disease. Within the same year, the Hawaiian Legislative Assembly passed “An Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy,” separating land for the isolation of people who were thought to spread the illness.

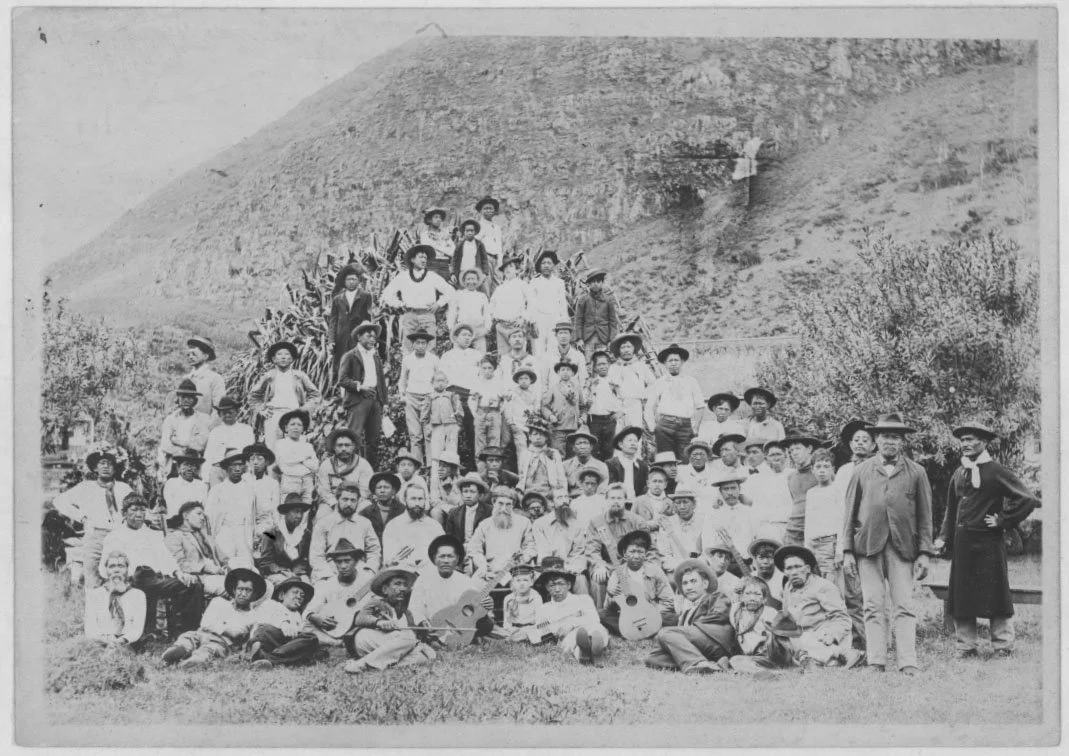

Kalaupapa leper colony in 1905. Hawaii State Archives. PD.

This act worked to tear families apart, and many began trying to hide sick relatives from officials out of fear that they might never see them again. Other families felt they had to disown relatives who were ill because of the shame that had been associated with leprosy.

In the 1900s, the circumstances took a turn for the better. As treatments for the disease became more heavily researched, different relief methods, including hot herb baths and herbal medicines, became more common. One of the primary treatments was chaulmoogra oil, which could be applied externally or by injection, but the oil wasn’t considered a cure due to its inconsistency. In 1941, the sulfone drug Promin was discovered as the first true cure, though it wasn’t until 1969 that Hawaii’s isolation and quarantine policies were abolished.

In 1980, the land was curated and preserved to become the National Historic Landmark site of the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement. The park works to maintain the memories of those who were banished there, while also supporting education on leprosy. Additionally, it is a symbol of loss, resilience and compassion for a place and people filled with a heartbreaking past.

Aside from Kalaupapa’s past, the park is home to some of the world’s tallest sea cliffs. At up to 3,900 feet tall, the cliffs provide some of the best views of Molokai and the greater Pacific. Visitors can also take tours to see Kalaupapa’s stunning ocean views and what is left of an idyllic village and calm atmosphere.

Because of its rich history, Kalaupapa National Historical Park is now an established travel destination, where visitors can learn about a unique Hawaiian history. “Your day in Kalaupapa will affect you,” said Randy King, founder of Seawind Tours & Travel. “There’s a lot of beauty, a lot of sorrow. Take it all in and imagine what it was like when a thousand people were living there, when they all worked together to create a wonderful place to live. Yes, people were banished there, but they found a way to work together, to make it home, and this is the story that inspires us today.”

Kelcie Lee

Kelcie is a second-year student at UC Berkeley majoring in history and sociology, with a minor in journalism. She developed her passion for writing and journalism in high school, and has since written for a variety of news and magazine publications over the last few years. When she isn't writing, Kelcie can be found drinking coffee, listening to music or watching the sunset.