Paige Geiser

Dive deep into the history of redwood logging, its ecological impact and where to witness what’s left of these natural wonders.

Giant redwood trees in California. Kevin Casper. CC0.

Along the coast of central California and southern Oregon, ancient redwood trees take nature’s title as the tallest trees in the world. These coastal redwoods can grow to a height of 367 feet (112 meters) and have a width of 22 feet (7 meters), the equivalent of a 35-story skyscraper. Upon reaching impressive heights, fossil records have shown that relatives of today’s redwoods were around in the Jurassic Era, almost 160 million years ago. The oldest redwood known today, Methuselah, sprouted in A.D. 217 and can be found in Redwood National Park. While Methuselah is especially old, any of the redwoods found along this coast can range from 500 to 2,000 years old.

The reason these trees have been able to thrive so long is due to the consistent climate of California’s north coast. The Pacific Ocean provides cool, damp air year-round, regardless of summer droughts, perfect for the needs of these towering trees. Nutrient-rich soil also plays a large role in their longevity. Complex soil induces the growth of fungi and moss, which continuously add nutrients to the soil. The combination of longitude, climate and elevation on this California coast makes it the only suitable environment for these redwood trees to grow naturally.

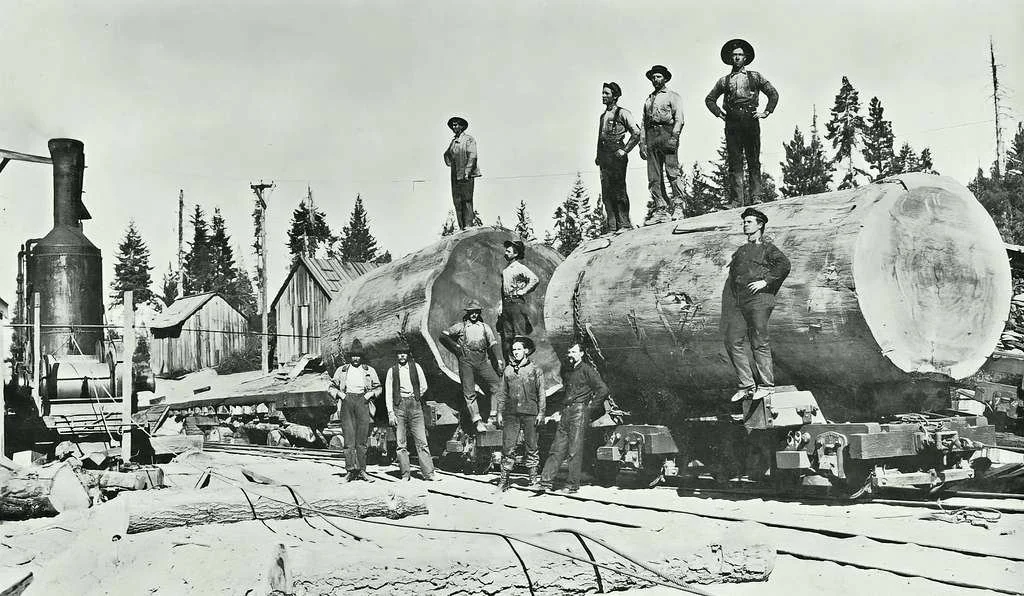

However, due to excessive logging, only 5% of the original redwoods remain. The logging of coastal redwoods began in the 1850s, when the gold rush brought Euro-Americans over to the West Coast. Redwood trees were prized for their size, durability and workability, which led to an abundance of saw mills along the California coast. Concern for the quick decimation of these redwood forests didn’t begin until 1910, when an organization called Save The Redwoods League was created. Once founded, this league purchased acres of forest at a time, working to protect the trees themselves. A decade later, the state of California used these purchased lands to establish three state parks. This state recognition did not stop logging because by the 1960s, industrial logging had removed almost 90% of all the original redwoods. Public demand pressured the government into creating Redwood National and State Park in 1968 and then expanding the park by another 10,000 acres in 1978.

Redwoods on flatcars ready to be lowered to the Kings River Lumber Company sawmill. Unknown. CC0.

Not only did this clear-cutting affect forest size, but it also plummeted the surrounding ecosystem into critical condition. According to Save the Redwoods League’s annual report, more than 600,000 acres of redwood forest need to recover in order to regain ecological function. The good news is that these trees can regenerate. Unlike most trees that rely solely on sexual reproduction, new redwood sprouts can come directly from a stump or a downed tree’s root system. This means that if given proper time, the forest will be able to heal itself. It may take a few hundred years for the forest to reach its original grandeur, but the fact that it is possible makes fighting for environmental reform that much more hopeful.

TO VISIT:

For those looking to travel to these ancient trees, Redwood National and State Parks, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park and Humboldt Redwoods State Park are some of the best places to visit. Redwood National and State Parks and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park contain the most untouched pieces of forest, offering a glimpse into the California coast before loggers arrived. Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park is among the most beautiful, with lush green ferns and dripping moss everywhere on the forest floor. Humboldt Redwoods State Park is by far the largest and lets travelers experience the magic of these redwood trees without leaving their car. For those looking for a closer experience, camping is permitted in Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, as well as a few other smaller parks. Traveling to these ancient trees not only takes one back in time, but also offers a perspective into how big the world really can be.

Paige Geiser

Paige is currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree in English with a minor in Criminal Justice at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. She grew up in West Bloomfield, MI, and has been fortunate enough to travel all throughout the country. She is an active member of the university’s volleyball team and works as the sports reporter for The Racquet Press, UWL’s campus newspaper. Paige is dedicated to using her writing skills to amplify the voices of underrepresented individuals and aspires to foster connections with people globally.